Jewish Feminism in Post-Holocaust Germany

Jewish feminism in Germany today is an expression of a wide-reaching renewal of Judaism occurring in many European countries since the early 1990s. German Jewish feminists built on the historical tradition of Jewish women’s movement in pre-Holocaust Germany. Since the 1990s Jewish feminism in Germany has taken many paths: egalitarian and religious paths, intellectual and academic paths, institutional developments, developments of gender-mainstreaming. Jewish feminism in Germany has multiple reference points and the interaction of different paths and developments has brought about lively culture of debate on Jewish feminist topics.

“One SabbathShabbat at our egalitarian The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan (prayer group), a prayer written by Bertha Pappenheim in 1935 was … recited instead of the usual psalm. ... It struck a particular chord in all of us. We suddenly became aware that we had a tradition of our own—that we could stand on our own ground and take further steps along it. Gradually we discovered the achievements of numerous magnificent women in Germany before the Holocaust.”

(Elisa Klapheck and Lara Daemmig, “Deborah’s Disciples.”)

Introduction

Jewish feminism in Germany today is an expression of a wide-reaching renewal of Judaism that has been going on in many European countries since the early 1990s. That women have their own movement within this development became evident at the first conference of Bet Debora in Berlin. Bet Debora is a Jewish women’s initiative founded in 1998. In May 1999 it invited female rabbis, cantors, and rabbinically knowledgeable and interested men and women from all over Europe to Berlin. This conference, the first of its kind in Europe, was attended by 200 participants from sixteen countries.

The unexpected phenomenon of Jewish feminism in Germany raises the question of a point of departure. What can Jewish women latch onto half a century after the Holocaust? Initially, the women who founded Rosh Hodesh groups and egalitarian congregations in the 1990s seemed merely to be catching up with what their counterparts in the United States and Great Britain had accomplished in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it soon became apparent that they had their own foundations on which to build—the historical tradition of the Jewish women’s movement in pre-Holocaust Germany.

The Jewish feminists of the 1990s have gone on to a variety of careers. Some became rabbis and scholars, others established progressive Jewish communities, and still others achieved positions in existing Jewish institutions and media; all attest to the ongoing tradition of Jewish women’s religious emancipation and highlight the legacy of their predecessors to the Jewish public sphere.

Meanwhile, approximately 200,000 Jews immigrated from the former Soviet Union, leading to a much broader diversification of Jewry in Germany. The immigrants’ perspectives on Jewish history and the Holocaust differ from those of the previous generation. Whereas Bet Debora saw itself as part of a European renaissance of Judaism and aspired to give German Jewish women a voice vis-à-vis Jewish feminism in the United States and Israel, the younger Jewish feminists are much more inclined toward global perspectives on Jewish feminist critique and politics.

Modern Jewish feminism in Germany emerged out of the pre-Holocaust achievements of Jewish women, which led to a revitalization of Jewish feminism after 1945. Since the 1990s, Jewish feminism in Germany has taken several paths.

Pre-Holocaust Origins of Jewish Feminism

In 1904 Bertha Pappenheim established the Jüdischer Frauenbund (League of Jewish Women). Together with like-minded militants, she fought for equal status for women in the Jewish community, for the right to vote and be elected to the community parliament and board, and for women’s right to professionalize their abilities. For Pappenheim, all these constituted no deviations from Jewish tradition. Rather, it was from her own deep religiosity that she developed thoroughly innovative thoughts on the socio-political significance of womanhood. Although Pappenheim held to the traditional ideal of women as “Guardians of the Family,” she liberated this ideal from its protected private sphere and expanded its significance by defining the entire Jewish community—and even the state as a whole—as “family.” Thus she claimed the public sphere as “women’s natural sphere of action.” What appeared to her to be the most obvious sphere of action was first and foremost social work, which she and thousands of other women established on a high professional level within the Jewish community in Germany.

Bertha Pappenheim was far from the only woman whose feminist thinking opened up a new dimension in Judaism. In 1930 Regina Jonas, the first woman rabbi in the world, completed her studies at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums (Academy for the Science of Judaism) in Berlin with a halakhic thesis entitled “Can Women Serve as Rabbis?” In it, she asserted that women by their very nature were particularly qualified for the rabbinate, because they were naturally endowed with such social competences as love of human beings, tact, empathy, and an easy approach to youngsters, all of which were as essential to the rabbinical profession as a continuation of Jewish tradition. Jonas employed the female grammatical form “Rabbinerin” (woman rabbi). She argued that women could not only perform the same functions as men but could endow the profession with a specifically female identity. She went so far as to maintain that a woman rabbi must, as a matter of course, fulfill the function of a “leader” (“Führerin”) in the congregation.

In their different ways both Pappenheim and Jonas expressed what many women, before and after World War I, were prepared to take upon themselves, namely to be the bearers of Jewish teaching, which they now intended to continue to create in a responsible manner and from a woman’s perspective.

The Holocaust put a violent end to this ingenuous awakening. After 1945 Jewish self-confidence was so shattered that the survivors clamored for the clichés of the “good old days” of the Orthodox style of the (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl. They perceived all attempts at innovation as threats to be automatically resisted.

Revitalization after 1945

In 1953, the Jüdischer Frauenbund was reconstituted by Lilli Marx (Düsseldorf) and others. But only a few of the outstanding Jewish women activists of the pre-war period had survived and still lived in Germany to engage themselves in the revived organization. One of them was Jeanette Wolff, who brought a Jewish woman’s perspective to bear on social policy in her dual role as both a member of Berlin’s Jewish Community parliament (Repräsentantenversammlung) and an SDP (Social Democratic Party) politician in Berlin’s House of Deputies (municipal parliament). However, the social activity of the Frauenbund at that time was primarily directed towards caring for the survivors. In the 1960s energy gradually declined and interest focused more on Israel. Younger women joined organizations such as WIZO in order to raise money for the new Jewish state by holding bazaars and other welfare-oriented activities. For an entire decade no other topic occupied the attention of Jewish women in the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora.

A few women, however, did air their Jewish-feminist views, although only as isolated voices and outside the communal mainstream. For example, in the 1970s Pnina Navé Levinson developed her own sphere of action as a professor at Heidelberg University; although she addressed a predominantly Christian-theological public, her books were the first post-Holocaust Jewish feminist publications in the German language. In the 1980s, when Daniela Thau was ordained at the Leo Baeck College in London as the first woman rabbi from Berlin since Regina Jonas, she had no prospect at all of finding a position as a pulpit rabbi in Germany. In fact, hardly any woman in the Bundesrepublik (West Germany) paid any attention to Thau’s ordination, to say nothing of believing she could serve as rabbi of a congregation. However, at the beginning of the 1990s Jessica Jacoby was successful in getting Jewish women to express themselves as Jews in Bundesrepublik society. As a Jewish feminist, Jacoby founded the Shabbes-Kreis (Shabbat Circle) in Berlin, the first Jewish feminist initiative in post-war Germany. First and foremost, this group criticized both veiled and explicit antisemitic attitudes in the German women’s movement, as well as the repression of Germany’s National Socialist past. Jacoby was the author of the first work on Jewish women’s self-awareness to be published in post-Holocaust Germany. What characterizes most of its contents is the ambivalence of living as a Jew in the “Land of the Perpetrators,” whether as a survivor or as one of the so-called “Second Generation.”

Jewish Feminism After the Fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 and the subsequent process of Germany’s unification were turning points in Jewish life. In the ensuing years, Jewish women kept discovering the remarkable work of outstanding Jewish women of the pre-Holocaust period.

In 1993 a Rosh Hodesh group was established in Berlin and an egalitarian minyan was founded, meeting in a private home. Quite independently of each other, liberal Jewish groups and egalitarian prayer groups arose in almost all the larger cities in Germany, some initiated by private individuals, some as new Liberal (Reform) congregations. All of these groups criticized the emptiness of the prevailing spiritual-religious life and sought an appropriate renewal that would relate to the earlier tradition of Liberal Judaism in Germany, for so long considered a thing of the past. Equality of the sexes constituted a common spiritual denominator. The woman who stood on the Lit. "elevated place." Platform in the synagogue on which the Torah reading takes place.bimahwearing a prayer shawl and head covering, who read from the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah scroll and fulfilled all the other religious functions of the service, became one of the identifying images of this new movement. In fact, women constituted a majority in the initiative. From the beginning, their much stronger presence in the minyanim could not be ignored; women frequently constituted two-thirds of the membership. Many trained themselves to be proficient in running a service, learned to read Torah, and questioned existing liturgy.

By the mid-1990s, this movement had established itself as a strong component of Jewish life. Although most of the official establishment had reservations about it, there were a number of political successes. A meeting of the Berlin Rosh Hodesh group on Lit. "weeks." A one-day festival (two days outside Israel) held on the 6th day of the Hebrew month of Sivan (50 days, or 7 complete weeks, from the first day of Passover) to commemorate the Giving of the Torah on Mount Sinai; Pentecost; "Festival of the First Fruits"; "Festival of the Giving of the Torah"; Azeret (solemn assembly).Shavuot 1995 led to the first political action within the community. The Berlin women protested against the recently decided mode of election for synagogue boards, according to which only men could be elected. A petition revealed a broad consensus opposed to the outdated stand of most of the community representatives. Drawing upon discussions of the 1920s, women demanded their right to perform religious functions in the synagogues. Already in 1930 Martha Ehrlich had functioned as the first woman board member (gabba’it) at the Rykestrasse Synagogue. The petition led to a change in electoral procedure two years later, so that each synagogue could henceforth determine whether it would accept women as board members. In 1998, after a difficult struggle, the members of the Egalitarian Minyan and the more traditionally oriented Egalitarian Service founded two years previously were officially granted the right to use the Oranienburger Strasse synagogue. From the first, it had active women board members.

In the interim, Bea Wyler, ordained in 1995 at the Jewish Theological Seminary,had in 1995 begun to serve as the first post-war woman rabbi in Oldenburg, Braunschweig, and Delmenhorst, constituting a further breach of taboo. Furthermore, beginning in 1995 the Union of Liberal and Reform Groups and Congregations held annual meetings in Arnoldshain; in 1997 they became the Union of Progressive Jews, a challenge to the Orthodox stand of the Central Council of Jews in Germany (Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland). One of the major points of contention was still whether women could perform active religious functions at religious services. However, reality had by now overtaken the issue: women who so desired stood alongside men on the bimah, not only in Berlin and other German cities but throughout Europe, where a similar development had taken place. In Minsk, Paris, Budapest, Oldenburg, Vienna, and Oslo—everywhere groups had been formed in which women had taken the initiative, even as rabbis and cantors. Great Britain played a leading role in this respect, since in 1976 Jacqueline Tabick had been ordained as the first European woman rabbi at Leo Baeck College.

Bet Debora

The 1999 conference on women’s issues sponsored by Bet Debora raised new issues for discussion. The program included such topics as: What would be the effect on Jewish tradition and transmission if women were to determine it equally? What themes and challenges would come to the forefront? Would the new activists, like their precursors before and after World War I, constitute a driving force in the revival of Jewish life in Europe and thus change Jewish identity in general?

From the outset, Bet Debora defined itself as European and stressed the uniqueness of European Jewry, which, after a decade of American and Israeli domination, was recalling its own culture and tradition. The 1999 conference participants included Katalin Kelemen, who had just been ordained as a rabbi in Budapest and headed a Reform congregation there; Nelly Kogan (Shulman), the youngest woman rabbi in Europe, who was born in Leningrad (St. Petersburg) and was involved in community-building in Minsk and other locations in the FSU; Daniela Thau, who lived in Bedford, England, and who, as Germany’s first woman rabbi after the Holocaust, had a decade earlier been unable to find a position in a German congregation; second-generation rabbis Sylvia Rothschild, Elizabeth Tikvah Sarah, and Sylvia Sheridan, who had already established a woman-related tradition in Anglo-Jewry; Diana Pinto of Paris, whose slogan of the “Voluntary Jew” had created a new concept of Jewish identity in the new political conditions in Europe; and Judith Frishman of Amsterdam, a feminist theoretician who presented the concept of “reconstructing a useable past” for Jewish women. In addition were Shoshana Ronen (née Elbogen) and Ilse Perlman (née Selier), who had studied at the Hochschule für die Wissenschaft des Judentums in the 1930s, only a few years after Regina Jonas, and Hanna Hochmann (née Gerson), who was at the time operating youth services in a liberal Berlin synagogue.

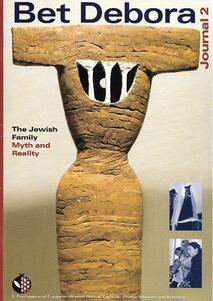

At a second conference in June 2001, Bet Debora dealt with a topic not limited to religion and of great significance to the future of the community and to the lifestyle of every individual member: Is there a future for the Jewish family? In Europe, as elsewhere, the Jewish dream family is no longer “normal”/ prevailing. Jewish men and women live as singles, single parents, in mixed relationships, as lesbians and homosexuals—in short, numerous lifestyles. Under the title “The Jewish Family: Myth and Reality,” the conference examined contemporary families from a Jewish perspective.

This second conference radically swept away old clichés. Among the topics addressed were the isolation of the single woman, inter-religious partnerships, same-sex weddings, single motherhood, and the status of children of non-Jewish fathers. In addition were sessions on topics that are usually taboo at Jewish conferences in Europe, such as Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunot, the “maternal imperative,” and domestic violence. Participants also discussed alternative family structures not based on biological relationships and the Jewish community’s responsibility for their integration. A revealing controversy arose at the plenary session on “Left Over—Living after the Shoah—Rebuilding Jewish Life in Europe.” It brought to light how much the revival of Jewish life was still in its infancy. Many participants saw themselves explicitly as “second generation,” linking their Jewish identity to the trauma of persecution passed on to them by their parents. Others, including the founders of Bet Debora, were wary of creating a self-paralyzing identity based primarily on victimization. They considered themselves the “first post-generation,” which no longer bases itself on the Holocaust but seeks to create something new while still drawing on the traditions of the past. The lively debate demonstrated that some of the younger generation were on the brink of emerging from the shadow of the Holocaust.

Bet Debora’s third conference, in May 2003, was dedicated to a more political approach: In what ways, and how much, do Jewish women engage in the power structures of their communities? What are the historical and social implications of their engagement? What do Jewish scripture and tradition have to offer to support women’s engagement in the power structures? What could the definitions of “power” and “responsibility” in Judaism be with regard to women’s activities? And how does all this interact with the rise of a new European Jewry, as well as with regard to the general European unification process?

Close to 200 Jewish women, as well as a remarkable number of men, from Eastern and Western Europe responded to Bet Debora’s invitation. The conference was designed as an open forum for the exchange of ideas. The 56 speakers included many Jewish community presidents from all over Europe; directors of Jewish institutions; spiritual leaders (rabbis and lay leaders); activists operating at various community levels; scholars who added historical and Judaic perspectives; and artists who provided cultural contributions. Speakers included Gabriele Brenner, president of the Jewish community of the southern German town of Weiden; Professor Dr. Rita Kleiman, head of the Academic Judaica Department and chairwoman of the Jewish community of Kishinev (Moldavia); Sylvie Wittmannová, founder of Prague’s first liberal Jewish community, Bejt Simcha, in 1992; Rabbi Gesa Schira Ederberg, principal of the Masorti center in Berlin and congregational rabbi in Weiden; Charlotte Knobloch, vice president of the Central Council of Jews in Germany and president of the Jewish Community of Munich; and academics, journalists, and feminist activists from virtually every European country and Israel.

In a revealing opening speech, Charlotte Knobloch spoke frankly of her own “experiences of power in Jewish institutions.” As at the previous conference, which started with the unveiling of a memorial plaque at the house in which Regina Jonas lived as a rabbi, the third conference also began with the inauguration of a memorial plaque, this time dedicated to Bertha and Hermann Falkenberg. Bertha Falkenberg had been the first woman member of Berlin’s Jewish Community parliament in 1926 and later survived Theresienstadt. Hermann Falkenberg, the founder of a liberal egalitarian synagogue in Berlin, died before the Shoah.

The theme of the third conference, however, prompted a dynamic all too common among women with political ambitions: ambivalence about openly striving for power. Many participants, including community politicians, initially confessed their uneasiness about the term “power.” Over the course of the conference this ambivalence declined and the necessity of participating in power structures was seen more clearly and pragmatically. The question shifted from whether Jewish women should want to attain power to how Jewish women could express their power in a responsible way. What are the criteria of responsibility? What are the fields in which participants should strive for their share of power and in which they can best contribute to the continuation of Jewish life in Europe? Participants recognized that there can be no single answer to these questions, since conditions vary from country to country. But all brought new ideas and inspiration back home, to be applied in concrete ways.

At all three conferences, Bet Debora made special efforts to achieve an equal presence of Eastern and Western European women. It turned out that many post-Soviet women considered “feminism” a bad word, equating it with communism. While conference participants tried to sort out a terminology for a mutual discourse, Eastern European women showed a remarkable self-confidence and readiness to step up and express their experiences and points of view. As a result, Western Jewish feminists did not “dominate” with their views or assign Eastern women the role of pupils. The sides met on equal terms and learned from each other.

After three conferences in Berlin, which of course had its own symbolism nearly 60 years after the Shoah, the conferences “wandered” to different European cities in order to give a special impulse to Jewish life there. The fourth conference, in 2006, was held in Budapest, developed and organized by “Esther’s Bag,” a group that edits a women’s page in the Hungarian Jewish newspaper Szombat. Other venues for conferences were Sofia, Vienna, Hoddesdon near London, Wroclaw, and Belgrade.

Over the years, Jewish women’s activities have become much more diversified, having an impact on the general Jewish structures in Germany. Germany’s national Jewish newspaper, Juedische Allgemeine, regularly publishes articles about the pros and cons of reforms related to women in Jewish tradition. In various cities the “(Yiddish) Rabbi's wife; title for a learned or respected woman.rebbetzins” of Orthodox rabbis teach women about heroes and female role models in Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah and Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud. Habad and the Ronald S. Lauder Foundation offer assertiveness-training courses for Jewish women, to instruct them on how to combine a professional career with a modern Orthodox lifestyle. Female rabbis such as Gesa Ederberg and Elisa Klapheck were offered pulpits in the Jewish communities of Berlin and Frankfurt. More female rabbis were ordained by the progressive Abraham Geiger Kolleg (founded 2003) in Potsdam.

Jewish Feminism in a New Generation

As post-Holocaust feminism emerged in Germany, Jewish institutions were tasked with integrating 200,000 Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union in the context of the so-called “Kontingentflüchtlingsabkommen” (refugee quota agreement) that allowed Jews a secure residential status in Germany. Only a very small minority of the newcomers were involved in feminist Jewish developments. Many had had their Jewish identity suppressed by the Soviet government, and experienced Jewish life for the first time in Germany. Since most German synagogues followed Orthodox practices, they were male-dominated. Children and youth of the 1990s, especially, were raised in such settings. Male domination and other hierarchies were seldom questioned.

Although the intellectual, activist, and religious work of Second-Generation Jewish feminists had created new possibilities, the next generation at first did not connect to them, in part because existing Jewish communities willfully ignored feminist challenges in order to maintain power relations. Bet Debora remained an important network for Jewish women across Europe and beyond, but unfortunately only a small number of younger Jewish women from Germany today know about it and take part in its conferences. History seems to repeat itself: as the feminists of the 1990s had to rediscover Bertha Pappenheim and Regina Jonas, the contemporary generation seems likewise to be cut-off from its predecessors.

Since 2000, however, partly in response to the large increase of the Jewish population, new Jewish structures in Germany have evolved that are not bound to conservative communities and attract increasing numbers of the new generation. A youth section of the Union of Progressive Jewry in Germany, Netzer, offers Machanot (Jewish summer camps) within an egalitarian setting and provides a Jewish education beyond orthodoxy and male domination. In 2010 the Jewish scholarship foundation Ernst Ludwig Ehrlich Studienwerk (ELES) began to support Jewish students’ intellectual development. ELES understands itself as pluralistic and requires scholarship recipients to respect different Jewish religious practices. It created a broad network of Jewish students and enabled many Jewish women to study and meet other Jewish feminists. Even though ELES is a small foundation, its effect—including within more conservative communities (in a sociological not denominational sense)—is profound. Students socialized in conservative settings experience alternatives and reflect on their Jewish socialization more openly. In 2010, the magazine Jalta – Positionen zur jüdischen Gegenwart (Positions on Jewish Presence) was founded as a public forum on contemporary Judaism. The title refers to the feminist Jalta from the Talmud. Jalta is a feminist magazine, documenting and inspiring feminist developments. It has published articles on Orthodox feminism, Women of the Wall, the Jewish Women’s Archive, alliances between Jewish and Muslim feminists, and queer Jewish movements. The magazine has had a significant effect on Jewish communal discussions in Germany.

Bet Debora, ELES, and Jalta all constitute a progressive Jewish conscience beyond the dominant community structures, not against or in opposition to these structures but as a supplement. Meanwhile, young adults are beginning to question male-dominated hierarchies from within their communities.

In 2016, the Union of Jewish Students Germany (JSUD) was founded. Some of the founders had been supported by ELES and most had been socialized in conservative communities. The JSUD has built up a women’s department to discuss issues of gender equality and raise the topic in students’ own communities. Religious pluralism is also an important topic. The JSUD supported the foundation of Keshet, a Jewish LGBTQI organization that aims to make queer Jewish perspectives visible in Orthodox and Conservative) communities. It cooperates closely with the European Union of Jewish Students (EUJS), which has been working in progressive settings for a longer time.

In 2019, a “Jewish Women Empowerment Summit” took place in Frankfurt, co-organized by the JSUD and the Council of Jews in Germany. To longstanding Jewish feminists, this conference seemed overdue, but given German Jewry’s conservative developments after the Holocaust, it was a historic moment. The summit was a public forum for discussing gender hierarchies in community structures and prospects for empowering women within and beyond these structures. While Bet Debora conferences are a forum for progressive political perspectives and focus on intellectual exchange, including the feminist religious potential of the Jewish tradition, the summit dealt with more practical questions of gender mainstreaming. It showed a variety of feminist Jewish perspectives: an Israeli trans person television personality, a feminist DJane, coaching for women, alternative family role models. This summit and the politics of the JSUD show that the new generation’s reference points come from a contemporary international context rather than from the Western and Eastern European experiences. Interestingly, or scandalously, the German Jewish feminist movement hardly played any role for the young women at the summit. Even the organizers did not refer to existing Jewish feminist contexts in Germany; most did not even know about them, having grown up in male-dominated conservative Jewish communities. Only a small number of participants located themselves within the movement.

To strengthen feminist Jewish perspectives will mean to connect different strands. Every generation can define its own understanding of feminism, and no generation has a one-dimensional perspective. Today’s feminist activists work with the hashtag #Claimyourspace. The former generations’ hashtag could have been #Claimyourlegacy. One of the challenges will be to overcome the gap between the feminists of the 1990s and current activists. To create change for the future requires knowing the/your past. One of the younger generation’s important tasks will be to reclaim its own history, but the conscience that will emerge will not be the same as that of feminists of the 1990s. Post-Soviet feminists, American and Latin-American feminists, Israeli feminists, and other narratives will diversify Jewish feminist history in Germany.

Gender-equality, women’s empowerment, and feminist activists have become much more accepted themes in the (conservative) communities in Germany. Bet Debora, ELES, the Union of Jewish Students in Germany, and Jalta remain spaces where critical perspectives on hierarchies can be discussed and feminist religious, scientific, and political issues are thematized. They remain necessary to give critical and progressive impulses to the conservative communities and can strengthen the work of the new generation.

Even though there is little knowledge about feminist Jewish history since the 1990s, its work was constitutive for the new generation today. There are female rabbis, there are feminist academics and feminist activists, there is an extensive literature, there are spaces that have called themselves feminist for a long time. Thus, the new generation has role models who are still active in feminist Jewish politics in Germany and beyond.

Belkin, Dimitrij, Hensch, Lara, Lezzi, Eva, eds. Neues Judentum – Altes Erinnern. Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2017.

Bet Debora Journal.

Cazès, Laura,“#Claim your space. Warum (feministisches) Empowerment in die Gemeinde gehört.” Jalta – Positionen zur jüdischen Gegenwart 6 (February 2019).

Goldberg, Barbara. “Vorbilder und Visionen.” Jüdische Allgemeine, February 26, 2019.

Jacoby, Jessica, ed. Nach der Shoa geboren. Jüdische Frauen in Deutschland. Berlin: Elefanten Press, 1994.

Kaplan, Marion A. The Jewish Feminist Movement in Germany: The Campaigns of the Jüdischer Frauenbund, 1904–1938. London: Westport, 1979.

Klapheck, Elisa. Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas—The Story of the First Woman Rabbi. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004. [In German: Fräulein Rabbiner Jonas – Kann die Frau das rabbinische Amt bekleiden? Teetz: Hentrich & Hentrich, 1999.];

Klapheck, Elisa. Wie ich Rabbinerin wurde. Freiburg: Dörfler Herder, 2012.

Klapheck, Elisa. “The Religious as the Political in Margarete Susman.” In Gender and Religious Leadership: Women Rabbis, Pastors, and Ministers, edited by Hartmut Bomhoff, Denise L. Eger, Kathy Ehrensperger, Walter Homolka. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2019.

Klapheck, Elisa and Lara Daemmig, eds. Bertha Pappenheim: Gebete/Prayers. Teetz: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2003.

Klapheck, Elisa and Lara Daemmig. “Debora’s Disciples: A Women’s Movement as an Expression of Renewing Jewish Life in Europe.” In Turning the Kaleidoscope: Perspectives on European Jewry, edited by Sandra Lustig and Ian Leveson. New York: Berghahn, 2006.

Konz, Britta and Bertha Pappenheim. “A New Look at the Concept of the Family.” Bet Debora 2 (2001).

Lustig, Sandra. “Left Over: Rebuilding Jewish Life in Europe.” Bet Debora 2 (2001).

Levinson, Navè Pnina. Eva und ihre Schwestern: Perspektiven einer jüdisch-feministischen Theologie. G. Mohn, 1992.

Peaceman, Hannah, Dissens als emanzipatives Potential: Emanzipationsprozesse in der jüdischen Gemeinschaft am Beispiel jüdisch-feministischer Kämpfe, forthcoming.

Peaceman, Hannah. “Brauchen wir eine Frauenquote? Pro: Mehr Frauen stärken die Demokratie – auch in jüdischen Verbänden.” Jüdische Allgemeine Zeitung, February 3, 2019.

Sheffer, Mimi. “Cantor+Women=Feminist?” In Be Debora Journal: Jewish Women in Europe: Creating Alternatives. Berlin: Hentrich & Hentrich, 2018.

Thau, Daniela. “Rabbi on the Margin.” Bet Debora 1 (2000).

Wolff, Jeanette. Mit Bibel und Bebel. Ein Gedenkbuch. Bonn: Verlag Neue Gesellschaft, 1980.