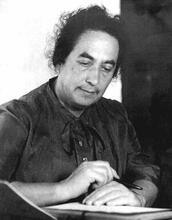

Sarah Shner-Nishmit

Sarah Shner-Nishmit was born in a Polish shtetl and was educated in Lithuania, where overhearing an anti-Semitic comment sparked her interest in Zionism. She hoped to immigrate to Palestine but was unable to before the outbreak of World War II. During the war, Shner traveled constantly to evade capture, working at labor camp and joining a Russian partisan group. Immediately after the war, she worked as a translator for Soviet authorities in Kovno and helped find new homes for Jewish children that had been hidden by Christian families during the war. Shner made aliyah in 1947 and subsequently began her writing career, which included children’s books and historical research. She also helped found Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot, where she lived until her death.

Early Life

The birth certificate of Sarah (Sonia) Shner-Nishmit was lost somewhere in Russia during World War I, but to the best of her recollection her birthdate was March 12, 1913. She was born in the (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl of Sejny (Poland), in the same house as her grandfather Meir Duschnitzki and her father Moshe Shelomoh, or Mosei, as he was known (d. 1931). However, her childhood years were spent wandering the length and breadth of Russia during wartime together with her father, her mother Lisa, and her sisters Manya (Miriam) and Lyuba.

Following World War I, she lived on the family estate, Duschnitza, in the region of the Lithuanian-Polish border. The name of the estate, which had been purchased by her father before the war and was confiscated by the Polish government in 1945, was similar to that of Shner’s maiden name, Dushnitsky. Shner speculated that her father’s forebears were residents of the nearby village, also called Duschnitza. Her mother ran the estate house together with Boris, her husband’s nephew. The family was very wealthy; the father was a surveyor by profession and a well-known public figure in the region. Of her home in Sejny, Shner recounted that it was “an open house, rich, always filled with numerous visitors and guests who would come to seek the help of my father on various matters.”

Shner attended elementary school in the city of Suwalki, not far from the estate. She later transferred to the Lithuanian town of Lazdei (Lazdijai), located ten kilometers from the Lithuanian-Polish border. There she studied at the town gymnasium, where the language of instruction was Lithuanian. In her memoirs of those days, she recounted that as a rule the few Jewish pupils there did not encounter antisemitism. However, in her autobiography she stated that at a ceremony held at the gymnasium on Lithuanian Independence Day, she was asked to recite a patriotic Lithuanian poem. “When I finished, the audience burst into applause. But when I came off the stage into the audience, I heard one of the dignitaries in the first row say: ‘True, the student read nicely, and her Lithuanian accent is perfect. But is it fitting for us to entrust the recitation of this poem on the national holiday of Lithuania to a Jew, of all people? Is February 16 her holiday?’” As a result of this incident, she reached the conclusion that “[I] had nothing of my own there … I was a stranger … an overnight guest. And I so longed for something of my own, even a miserable little piece of land, but my own.” At that point, her interest in Zionism began.

In the 1930s Shner moved to Kovno to study at university. She initially studied medicine, but soon changed her field of interest, switching to psychology and education. She also joined the He-Haluz ha-Za’ir movement, becoming one of its key activists in Kovno. As part of her work in the movement she would often pass through Lithuanian towns to serve as youth-group leader in existing chapters of the movement or to set up new chapters. She hoped to immigrate to Palestine, but the reduction in Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah certificates following the Arab riots of 1936 disrupted her plans and she was forced to remain in Kovno.

World War II

On October 10, 1939, shortly after the outbreak of World War II, an agreement was signed between the Soviet Union and Lithuania, handing Vilna over to Lithuania in exchange for the use of Lithuanian army bases by Soviet forces. During the Soviet occupation, Shner divided her time between Vilna and Kovno. She became principal of the Tarbut school in Vilna, replacing Samuel Amrant, who was forced to resign since Polish citizens were no longer allowed to hold public positions.

When the German army invaded the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941, Shner, together with her mother and sisters, decided to escape to the Soviet Union. She had married a man named Izia Sapir but lost him at the beginning of the war. They embarked on a long, tortuous journey through western Belorussia during which Shner lost contact with her family. After wandering through forests and between ghettos in Belorussia, she arrived at the labor camp at Dworec in the Nowogrudok district of western Belorussia. The camp had been set up in the autumn of 1941 by Todt, a German engineering firm that supervised both the construction of buildings vital to the German army and the paving of roads and building of bridges required to facilitate the army’s passage in German-occupied areas. The camp had a quarry where the Jews worked mining stones. A Judenrat was even set up in Dworec which attempted to provide food for the forced laborers.

Living conditions in the camp were harsh and the Jews were frequently injured during the mining and transport of the stones. Shner initially worked as an interpreter and cook for the camp commander, and later as a nurse at the hospital, where most people refused to work because of the typhus epidemic raging in the camp. Since she had already suffered from the disease as a child, Shner was not afraid of contracting it. Already in the early days of her internment in Dworec rumors reached the camp of the liquidation of nearby ghettos, among them Lida, Nowogrudok, and Slonim. In the spring of 1942, when new reports came of the destruction of other ghettos in Belorussia, the inmates of the camp decided to make contact with the partisans.

Shner joined the local underground and on the day the camp was liquidated she managed to hide, thereby escaping the fate of the other camp inmates, who were sent to their death. In December 1942, after lengthy wanderings, she reached the partisans’ camp situated on the banks of the Shchara River and commanded by a Russian officer named Bolak. Their field of operations was the vicinity of Ruda, Jaworska (Yavorskaya) and other villages. When Shner arrived at the camp, her legs were wounded and frostbitten. She introduced herself as the wife of a Russian officer missing in action, but her false identity aroused suspicion, both because her fluent Russian differed from that of the others in the camp and because she did not drink liquor. She was permitted to remain in the camp despite the fact that she could offer no apparent contribution to the operations of the partisans. Shner was put to work as a typist and also performed kitchen chores and served as a nurse in the camp hospital.

German units would periodically invade the camp, making it necessary for the partisans to move from place to place. At times, they marched distances of fifty to sixty kilometers in a day and were even forced to wade through the frozen Shchara River. These treks were very difficult for Shner since they caused her leg wounds to reopen. Despite the German pursuit, their brigade (known as Pobeda, or victory) grew considerably during 1943, totaling over one thousand fighters divided into three battalions.

Towards the end of the war, with the Soviet army approaching Minsk, the Germans began to retreat from Belorussia, attacking groups of partisans as they went. As a result of the intense pursuit, the partisans were often forced to scatter for cover. During one of these skirmishes, Shner lost her way and almost fell into German hands, but she eventually managed to link up with the members of her group and avoid capture.

Postwar Life in Europe

After the war, when stories of the death camps and the Warsaw Ghetto uprising began to reach Shner, she had difficulty coping with the sense of grief and destruction. As she later said of her feelings following her liberation: “One chapter of my life had ended. I don’t know why I was privileged to survive—certainly not due to my own merit. During my long and difficult journey, I encountered many good people, both Jews and Christians, who aided me in my struggle to stay alive, who fed me a hunk of bread when I was weak with hunger, who sheltered me and gave me a place to rest my head when I knocked on their door trembling with the rain and cold. It is thanks to them, I think, that I have made it to this point. Perhaps it is thanks to such people and others like them that the world exists. …”

As part of the repatriation operations, citizens of Poland began to return to their country from the Soviet Union. Shner, who did not know whether her family had survived, returned to Kovno in late 1945. In Kovno she worked for the Soviet local authorities as a translator and, for about a year, helped smuggle Jews move to Poland. She was also able to locate her mother and one of her sisters, Manya, who had given birth to a son, Mishka, while living in the Soviet Union but whose husband Aryeh (Lolya) Gink had perished in the Holocaust. Lyuba, the second sister (d. 1974, in Israel), was still in Russia. While Shner was determined to travel to Łódź, which had become a center of Zionist activity in Poland, her family members did not share her feelings; in December 1945, she left Kovno, arriving in Łódź by herself. She was also motivated to leave Kovno because she had learned that the secret police had found out about her smuggling activities. Her mother lived in Kovo until 1974; Shner never saw her again after her escape.

In Łódź she met Leibel Goldberg (Aryeh Sarid), an emissary from Palestine who was engaged in reclaiming Jewish children from Christian families. Despite her strong desire to immigrate to Palestine, Shner agreed to help him in his work. Following the establishment of the Zionist Coordinating Group for the Redemption of Children in Poland, Sarid and Shner succeeded in locating dozens of Jewish children who had been adopted by Christian families and restoring them to their heritage. Her efforts brought her to Warsaw as well. During her work, Shner was plagued by frequent doubts and often asked herself what right she had to remove children from homes where they had made a good adjustment and had no knowledge of their Jewish background. But in a number of cases, she discovered that the children had suffered physical or sexual abuse at the hands of their adoptive families; as a result, she decided that these cases justified the removal of any child who could be rescued from such settings. Shner worked for the Coordinating Group as a representative of the Dror movement and coordinator of its Education Section.

In 1946 Shner also worked for the Jewish Historical Institute (Zydowski Instytut Historyczny) in Warsaw and was involved in the uncovering of the archives of historian Emanuel Ringelblum, who had secreted the collection in milk jugs in the Warsaw Ghetto before perishing in the Holocaust. She participated in the opening of the containers and the processing of the material. It was also during this period that she met her future husband, Zvi Shner, whom she married in late 1946. Zvi died on August 22, 1984.

Life in Israel

In late December 1947 Shner traveled alone from Poland to Palestine while pregnant with her first child, Avner. Her husband followed eight months later. During her first years in Israel, she worked at a school in Akko (Acre), teaching children of immigrants. In 1949 she was among the founders of A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot, where she lived for the rest of her life. Two more sons, Giora (b. 1951) and Moshe (b. 1955), were born on the kibbutz. After her aliyah Shner was involved in teaching and education and wrote several children’s books. She also collected testimonies from Holocaust survivors and engaged in historical research. In 1955 she joined the senior staff of the Ghetto Fighters Museum in the kibbutz, where she was an active member until the age of 92.

Through her books and children’s stories Shner sought to instill an awareness of the Holocaust in children and young people. The best known of her children’s books is Ha-yeladim me-rehov Mapu (The Children of Mapu Street), which describes the attempts of a group of children to survive in the Kovno ghetto. Since the book was first printed in 1958 it has appeared in several editions. Shner later wrote Yaldah bi-melunah (Girl in a Kennel), containing three stories of children who owed their lives to a dog that protected them. Her autobiography appeared in 1986. In the introduction she wrote: “Throughout the years that I worked in our ‘house of testimony,’ Bet Lohamei ha-Getta’ot, I recorded the testimonies of hundreds of survivors—but when it came to my own life, I was unable to speak. I don’t think I would ever have told the story of my life … if Bet Lohamei ha-Getta’ot and my kibbutz had not initiated the Sifrei Edut [Books of Testimony] project.” In her later years she worked on a historical study of the ideological and philosophical roots of Nazism.

Sara Shner-Nishmit died on October 23, 2008, at the age of 95.

Selected Works

Books in Hebrew:

A Different Pedagogical Poem. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1996.

And I Knew No Rest. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1986 (autobiography).

Even the Dead Knew No Peace. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1998.

Girl in a Doghouse. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1998.

History of the Holocaust and the Resistance. Tel Aviv and Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1961 (reference book for teachers and youth-group leaders).

Once More the Daffodils Bloom. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 2003 (packet for Holocaust Remembrance Day).

The Battle of the Ghetto. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1968.

There Were Pioneers in Lithuania, 1916–1941: The Story of a Movement. Tel Aviv/Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1983.

Shner-Nishmit, Sarah, and Natan Gross, comp. Children in the Ghetto. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1980.

Shner-Nishmit, Sarah. The Children of Mapu Street. Translated into English by David S. Segal. Philadelphia: 1970.

Articles in Hebrew:

Shner-Nishmit, Sarah. “Were the German masses aware of the extermination?” Mi-Bifnim 35 (1974): 552–559.

“The purpose—posterity: Jewish documentation during the Holocaust era” (Hebrew). Edut 6 (1991): 77–94.

“Rescue activities in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania (Late June 1941–July–August 1944).” In Nisyonot U-Pe’ulot Hazalah bi-Tekufat ha-Shoah, edited by Y. Gutman, 238–275. Jerusalem: 1976.

“The Righteous of the Nations in Occupied Lithuania.” Dapim le-Heker ha-Sho’ah ve-ha-Mered, second series, collection I (1970): 317–324.

“The study of the Holocaust and Israel’s wars.” Mi-Bifnim 36 (1975): 495–510.

“Understanding the use of Tarnung: Concealment and deception in the extermination of the Jews in Eastern Europe.” Dapim le-Heker Tekufat ha-Shoah 4 (1986): 53–82.

“The Ponar diary of Hoitold Sokowski.” Zemanim 12 (1983): 95–101.

“A diary like this one: Daily notes from the early period of the Berihah organization in Lithuania.” Kivunim 30 (1986), 69–82.

“New research on the resistance and destruction of the Jews in the Holocaust.” Mi-Bifnim 45 4–3 (1983): 361–370.

“Study on the ties between the Lithuanian Fascists and the Third Reich.” Dapim le-Heker ha-Sho’ah ve-ha-Mered, second series, collection II (1973): 259–264.

“Diaries of children and young people during the Holocaust.” In Le-Zikhro shel Janusz Korczak: Arba’im Shanah Le-Herazho, edited by N. Czisling, E. Lahad, 39–49. Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot: 1986.

“Murderers and the Righteous of the Nations.” Dapim le-Heker Tekufat ha-Sho’ah 14 (1998): 273–312.

Interview by Miri Freilich. Tape recording, October 2003.