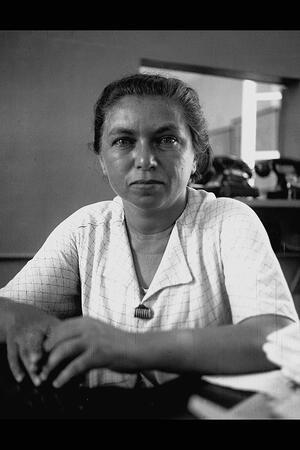

Bracha Habas

Bracha Habas immigrated to Palestine with her family in 1906, where she attended the Training Seminary for Women Teachers. In 1919 she joined the socialist-Zionist party Ahdut ha-Avodah, through which she established innovative classes for young working women. In 1926 Habas traveled to Germany to deepen her knowledge of pedagogical theory. She returned to Palestine and worked at an elementary school for six years. During this time Habas also published stories and articles in Davar. In 1931 she co-founded its children’s newspaper, Davar le-Yeladim, to which she submitted material weekly for 25 years. In 1935 Habas became a permanent staff member of Davar’s editorial board. Habas is considered one of the first professional women journalists in Erez Israel; enumerating on Habas’s 48 publications, Rahel Adir described her as “the recorder of Yishuv history.”

Family & Immigration to Israel

Editor, writer and one of the first few women journalists in The Land of IsraelErez Israel, Bracha Habas was born in Alytus, a town in the district of Vilna (Lithuania) on January 20, 1900, to a wealthy and cultured family of merchants who were actively involved in communal life. (The family name is the acronym of Hakham Binyamin Sefardi or Hakham Beit Sefer [School].) Her grandfather, Rabbi Simha Zissel, the scion of a rabbinic family in Vilna (that of the Yesod, Yehudah ben Eliezer; Yesod is an acronym for Yehudah safra ve-Judge in Jewish law cases; member of a rabbinic court.dayyan , “Yehudah scribe and judge,” d. 1762), was the first member of the family to turn to trade, opening a large general store that became a center of life in the township. On the other hand, her father, Rabbi Israel, successfully combined business with study: ordained in the yeshivas of Volozhin and Slobodka, he turned to business as a leather merchant only after marriage; nevertheless he continued to teach and to lecture on Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah-related subjects and, on joining the Lit. "love of Zion." Movement whose aim was national renaissance of Jews and their return to Erez Israel. Began in Russia in 1882 in response to the pogroms of the previous year. Led to the formation of Bilu, the first modern aliyah movement.Hibbat Zion (Lovers of Zion) movement, was extremely active in converting people to the Zionist ideal and the study of Hebrew. He established a branch of Safah Berurah (“Plain Language,” a society founded in Jerusalem in 1889) in his hometown, was among the founders of the Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi movement in 1902 and, once in Erez Israel, edited a non-partisan religious Zionist journal, Ha-Yesod (1931). Habas’s mother, Nehama Devorah, daughter of Rabbi Nahman Schlesinger (a descendant of Rabbi Eliyahu, the Vilna Head of the Torah academies of Sura and Pumbedita in 6th to 11th c. Babylonia.Gaon, 1720–1797), was also highly educated. Her father taught her Bible and she was fluent in both spoken and written Hebrew (an exceptional phenomenon among women born in the 1870s).

Habas was the fourth child in a family of seven. When the oldest son reached Lit. "son of the commandment." A boy who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbar mitzvah age, her father decided to immigrate to Erez Israel and fulfill his life’s dreams; firstly, to abandon his occupation as a merchant and instead earn his living by farming; secondly, to protect his children from the increasing secularism of East European Jewry and educate them to a religious-Zionist life in Erez Israel. In the summer of 1908, the Habas family immigrated to Palestine. However, the encounter with their new homeland resulted in sorrow, disappointment and wandering. Their first stop was Petah Tikvah, where her father wished to purchase an orchard to cultivate and provide for his family. But the family found the heat there unbearable, the children developed skin and eye ailments, and Nehama was overwhelmed by the combination of household duties to which she was unaccustomed (laundry and bread-making) and the hitherto unfamiliar local foodstuffs, such as tomatoes, eggplants and olives.

Their second stop was Haifa, where their alien status and loneliness were even harder to bear. Because of the crowded living conditions of the city’s small Jewish community, they were compelled to rent quarters in an Arab neighborhood and live among people with whom they had no common language. Furthermore, Arab culture predominated even in the Jewish school, where only Arabic and French were taught, no Zionist education was provided, and the Jewish women teachers went around veiled. Their third stop was the Jewish neighborhood Neve Shalom near Jaffa (founded in 1890). Although even here they had to continue coping with unexpected conditions (such as moving house every year according to the Muhram law), henceforth there was no more wandering.

Education

Israeli journalist and children's author Bracha Habas. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Neve Shalom was a religiously observant neighborhood, with religious schools (Talmudei Torah and yeshivot) for boys, but nothing for girls. No religious schools had as yet been founded for them. Thus their father was reluctantly compelled to send Bracha and her sisters (Hemda, Batsheva and Sarah) to a girls’ school in nearby Neve Zedek. This was a modern Hebrew school, with an excellent staff (including Dr. Nisan Turov, 1877–1953), which provided its pupils with high-level studies and a wide-ranging liberal education (all this despite the lack of even basic equipment and Hebrew textbooks). Since there was no religious education, their father was obliged to minimize the damage by gathering his daughters during their free time (particularly SabbathShabbat afternoon) and teaching them basic texts in Judaism, such as Ethics of the Fathers, Ibn Pakuda’s Hovot ha-Levavotand Judah Halevi’s Kuzari. Nevertheless, the religious gap between him and his daughters only increased.

The storm broke out when the oldest daughter, Hemda, finished school and wanted to continue her studies at the newly established Training Seminary for Women Teachers (later the Lewinsky Teachers’ Seminary). Her father objected violently and the family dispute attracted so much attention from neighbors that delegations of teachers and parents came to their home in an attempt to persuade him to change his mind. Finally, he gave in, with the result that not only Hemda but all the sisters attended the seminary.

Career in Education

Bracha’s educational career was similar to that of Hemda: in 1914 she completed elementary school and in 1921 graduated from the Teachers’ Seminary. (Her college career was interrupted by the events of World War I, when the family, like all Jewish residents of Jaffa, were compelled to transfer to Petah Tikvah and Kefar Sava.) In 1919 she joined the socialist-Zionist party, Ahdut ha-Avodah, which gradually came to occupy a major place in her life—an organization to which she contributed the best of her abilities and talents, in education and journalism. As a party member, Habas joined its cultural committee and participated in its educational institutions. In her final year of studies, she counseled and taught working youngsters in a club which she established in Neve Shalom. Later she was among those who established and were active in Beit ha-Yeladim (The Children’s House), an afternoon club for workers’ children, as well as the first school for working youth (Noar Oved) in Tel Aviv. In the latter she developed unprecedented studies for young working women. The innovative aspect of this work lay in the fact that Bracha not only initiated and developed appropriate courses of study in a variety of subjects, but that she succeeded in getting together a class of young housemaids, most of them Yemenites, who diligently attended classes every evening. As her friend Ita Eig-Faktorit wrote: “She prepares for this work, day by day, as if for sacred worship; she arrives early, prepares the heder (room), a kind of canvas tent erected by amateurish hands on the sands of Tel Aviv, on the road to the sea, and welcomes the girls at the entrance to the class, as a sense of festival pervades the heder, so neatly arranged and tastefully decorated.”

In 1924, Habas left Tel Aviv in order to contribute with her education and professionalism also to rural youth. For two years (1924–1925), she taught in the Lit. "village." The dominant pioneer settlement type of the Jews in Palestine between 1882moshavah of Kinneret and later for a short while at the Meshek ha-Po’alot (Women’s Farm) at Nahalat Yehuda, where she both taught and worked at the chicken coop. It is worth noting that throughout all these years her father maintained ongoing contact with her, despite his pain and disappointment. He sent her long letters in which he not only conveyed news of home and family, but also discussed issues of outlook and ideology even as he never ceased to try to bring her back to her origins and to persuade her that there was no conflict between her socialist theory and religious belief.

In 1926, seeking to further her schooling and deepen her knowledge of up-to-date pedagogical theory, Habas went to Leipzig, Germany. Here she earned her living as a teacher at the Zionist school headed by Dr. Vaskin and registered for courses in pedagogy at Leipzig University. A year and a half later, in 1927, she returned to Palestine and joined the staff of Beit Sefer le-Dugmah (the model elementary school) attached to the Women Teachers’ Seminary. She worked there for six years, both teaching in the elementary school and serving as a counselor to the upper classes of the seminary (1928 to 1933). At the same time, she did not neglect the school for working youth, where she taught both boys and girls voluntarily several times a week.

Davar le-Yeladim

Throughout these years, she was also writing, perhaps because Joseph Hayyim Brenner (1881–1921), her literature teacher at Lewinsky, encouraged her to do so. Certainly her encounter with him as both teacher and author exerted a great influence on her and on her decision to adopt writing as a way of life. Her first article appeared in Ba-Hathalah (At the beginning, 1921), which was published by the Ahdut ha-Avodah’s Cultural Committee. In it she described her follow-up work with her young worker pupils. In 1922, when the literary journal Hedim (Echoes) began publication, under the editorship of Asher Barash and Ya’akov Rabinovitch, Habas found a welcoming base there, as well. When she left for Germany, she continued to send her essays and stories to the weekend supplement of Davar, the newspaper founded in 1925, this time at the invitation of its editor, Berl Katznelson. At the same time (1926) she published a vocalized rhymed booklet for children, Tik ha-Segulah (The Exceptional Bag), which contained stories of her family and childhood in Alytus.

On returning from Germany, Habas continued to publish stories and articles in the Davar supplements, mainly about her experience with, and observations of, children. In the autumn of 1931 Katznelson invited her to join Yizhak Yaziv (1890–1941) in founding a children’s newspaper. As Uriel Ofek (who edited Davar le-Yeladim in the 1960s and 1970s) wrote: “A few days after Rosh ha-Shana (September, 1931), two figures marched through the deep sands of Little Tel Aviv and turned towards the house of the artist Nahum Gutman (1898–1980). They were the tall Yizhak Yaziv and Bracha Habas with her long braids. The two told the artist about the plan of the Davar editorial board to publish a special supplement for children and asked him to illustrate it. On that day Davar le-Yeladim was founded.”

Bracha Habas was involved with the weekly for twenty-five years, sometimes as editor. She wrote editorials, stories and reports. Even when she traveled abroad on missions far and wide, and also after her marriage to David Hacohen (1898–1984) in 1946 and her subsequent move to Haifa, she continued to submit material every week.

Work Abroad & Joining Davar’s Editorial Board

In 1933 Habas took a leave from teaching and journalism in order to go to Vienna for further training in pedagogy and psychology. While in Vienna she was invited to Warsaw for literary work at the He-Halutz journal and also published Dapim le-Ivrit and a first collection of Yaldei he-Amal (The Child Laborers, a collection of stories for youngsters about child workers all over the world). From Warsaw she went as a correspondent to the Zionist Congress in Prague, where she met Berl Katznelson, who invited her to establish “The Youth Center” of the Histadrut Labor Federation and serve as editor of its publications. She headed this center from 1934 to 1935, combining her professional skills as educator, author and editor. The result was a long list of booklets, which included Vienna (1934); Tel Hai—A Collection (1934); Rahel (1934); The Kinneret Four (1935); The Life of Alexander Zeid (1938); Homah u-Migdal (Stockade and Tower: The New Settlements During the Blockade Years, 1939); Ha-Godrim ba-Zafon (The Fence Builders of the North, 1939); Hayyim Sturman: The Man and His Deeds (1939) and her own stories (Little Heroes:Lives of Children in Erez Israel, 1934).

In 1935, Davar sent her as its correspondent to the Zionist Congress in Zürich. In the same year the Youth Center closed down and she was invited to become a permanent staff member of the Davar editorial board. She also joined the editorial board of the women’s paper Devar ha-Po’elet under the editorship of Rahel Katznelson, which had been founded in 1934. Of her work at Davar the poet Shimshon Meltzer (a colleague at the paper who later became editor of Davar le-Yeladim) wrote: “Bracha Habas was at the time the only woman on the editorial board. She was the paper’s female essence and its soul. She was among the last to express an opinion at meetings of the editorial board. She expressed that opinion quietly, briefly and clearly. And not only was her opinion heeded; it was often considered the most balanced. Whenever someone had to be appointed to a new position, such as starting a new column or even an additional newspaper, she was always the prime candidate.” Indeed, in addition to her regular work on the editorial board, she initiated and wrote the “Column for New Immigrants” and the supplement Davar la-Golah (Davar for the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora).

The Significance of Habas’s Writing

In his article “Between Two Meetings,” the historiographer Getzel Kressel portrayed Bracha Habas as the first professional woman journalist. (Mordechai Naor added that she was the first woman to report from the scene of an event.) Kressel wrote: “When I go back and try to give a bird’s eye view of the early days of Hebrew journalism, I try in vain to find the ‘species’ of woman journalist. … Of course, here and there a woman’s name appears, but Bracha was without a doubt the first to make journalism her permanent form of employment and persisted in it for decades.”

Kressel also refers to two genres of journalism which characterized her writing: one was the social reportage, through which she “covered” the real life of the working class at all stages of life and at every age; the other was lyrical reporting, which although it always dealt with work-related topics, did so from a slightly different perspective, far from the limelight, and in an emotional, involved manner. However, her writing was free of adornment or extravagance, excelling in conveying experience in a direct and clear style.

An additional contribution of Habas’s was the scores of books, pamphlets and anthologies that she wrote or edited, which via interviews, personal witnessing and documentation, told the story of “Working Erez Israel” (its institutions, activities, leadership), a story which actually told of the entire Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv enterprise. It was not by chance that her colleague, Rahel Adir, in enumerating her forty-eight publications, described her as “the recorder of Yishuv history” or “The chronicler of our times.” In 1940, Am Oved Publishing House was established and as usual she took upon herself the editorship of a series of books for young people of various ages (Shaharut [for Early Years], La-Yeled [For the Child], Min ha-Moked [From the Focal Point). Even her works for young people as well as those for adults became basic works in the critical history of the country, from Yishuv to state (settlement and struggle, Holocaust and illegal immigration, World War II and the War of Independence, the new Israel, Aliyah and absorption). Examples include: The Riots of 1936 (1937), Youth Aliyah (1941), Close Brothers Who Were Expelled (1943), Letters from the Ghetto (1943), The Second Aliyah (1947), Kinneret during the Trial Period (1950), David Ben-Gurion and His Generation(1952), The Ship that Won: Exodus 1947 (1954), The Gate Breakers, Vol. 1: The Story of Aliyah Bet (illegal immigration, 1957), The Gate Breakers, Vol. 2: From the East and from the West (1960), Benot Hayil (Women of Valor, The Book of the ATS, 1964), the story of the women volunteer soldiers from the Yishuv during WWII, Movement Without a Name: Volunteer Work by Veteran Settler Youth Among New Immigrants (1964).

Habas’s final work, published posthumously, was He-Hazer ve-ha-Givah (The Courtyard and the Hill: The Story of Kevuzat Kinneret (1969).

Personal Life & Legacy

Bracha Habas’s first marriage in 1924, at Kevuzat Kinneret, to Joseph Barchenko, the brother of Haganah leader, MK and minister Israel Galili, was very brief. In 1946 she married David Hacohen, a founder and director of Solel Boneh, who served as a member of Lit. "assembly." The 120-member parliament of the State of Israel.Knesset for six terms (1949–1969) and was Israel’s first ambassador to Burma (1953–1955). In 1948 Habas and Hacohen jointly published a book on the Erez Israel delegation to the Congress of Asian nations, held in New Delhi, in which both of them participated (Twenty Days in India,March–April 1947). The time she spent in Burma as the wife of Israel’s ambassador also resulted in books related to the region: Pagodot ha-Zahav (The Golden Pagodas, 1959) and Distant Worlds: Impressions of a Journey to the Far East (1969).

Throughout her life, Bracha Habas sought also to engage in belles-lettres. From time to time, she published short stories (such as “Pangs of the Motherland”) and books for youngsters such as Mi-Karov (From Nearby: Landscape and Person, 1940) and Story of a Young Illegal Immigrant (1966), but she never managed to write an entire novel. As her young writer friend, Yehudit Hendel, said:

“During her last years, Bracha dreamt of one book she wanted to write, her own book, about her own life. She always wrote other books, about other people, and postponed her own story. And that too because of an overwhelming sense of duty, although with much pain. I recall that a year ago [1967], when she was asked to write the book on Kinneret, she asked me for my opinion. And I have to admit that I said, ‘Bracha, this year it’s Kinneret, next year there’ll be something else, there’ll always be something. Let it be, write your own book, which you so long to do.’ She listened. ‘You’re right,’ she responded. ‘I must.’ But she decided otherwise. With her, duty came before desire. She completed the book on Kinneret, but as for her own book, the book she dreamt of, she never even started it.”

Bracha Habas died of cancer on July 31, 1968.

Adiv, Rahel. “Writing the History of the Yishuv.” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 79–82.

Darr, Yael. Called Away from Our School Desks: The Yishuv in the Shadow of the Holocaust and in Anticipation of Statehood in Children’s Literature of Eretz Israel, 1939–1948. Jerusalem: 2006.

Darr, Yael. A Canon of Many Voices: Forming a Labor Movement for Children, 1930–1950 (Kanon bekhamah kolot: Sifrut hayeladim shel tenu‘at hapo‘alim, 1930–1950). Jerusalem: 2013.

Darr-Klein, Yael. “The Legend of the Emerging Nation: The Stories for Children and Young Adults Edited and Written by Bracha Habas in the Years 1933–1940” (Agadat hale’om hamithaveh: Hasipurim liyeladim uleno‘ar she‘arkhah vekatvah Berakhah Ḥabas bashanim 1933–1940), M.A. Thesis, Tel Aviv University, 1997.

Eig-Faktorit, Ita. “My Bracha [Things that Happened].” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 35–41.

Habas Hacohen, Bracha. “My Father’s House.” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 9–31.

Hendel, Yehudit. “The Private Bracha.” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 55–57.

Kressel, Getzel. “Between Two Meetings.” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 61–74.

Ofek, Uriel. “Bracha of Davar le-Yeladim.” In My Father’s House. In memoriam Bracha Habas, from letters of condolence. Haifa: 1969, 77–78.

Naor, Mordechai. “The First Woman Reporter: Bracha Habas and Her Path in Journalism and Literature.” In Gentlemen, the Press. Chapters in Written Communications in Erez Israel, 63–76. Tel Aviv: 2004.

Tidhar, David (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Pioneers and Builders of the Yishuv. Vol. 3, 1128–1129. Tel Aviv: 1949.