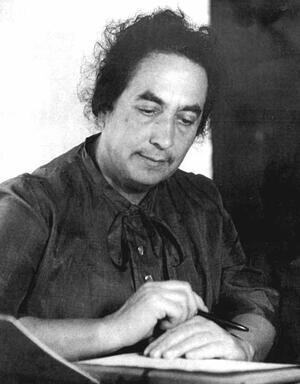

Recha Freier

Recha Freier established Youth Aliya, the movement to bring Jewish children from Germany to Palestine, enabling thousands to escape Nazi persecution and build new lives in pre-State Israel. It was not until the end of her life that she received formal recognition for the visionary initiative that saved so many Jewish children.

Institution: Serem Freier.

A social activist and musician, German-born Recha Freier founded Youth Aliyah in 1933, just as Hitler came to power. After trying unsuccessfully to find employment for five Jewish teenagers in 1932, Freier had an alternative idea, which became the basis for Youth Aliyah: to send teenagers to Palestine to train as agricultural pioneers on kibbutzim. Freier asked Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah, to take responsibility for the youth upon their arrival in Palestine. Tensions between Freier and Szold eventually led to Freier’s withdrawal from the Youth Aliyah upon her immigration to Palestine in 1941. At that time Freier became very involved in the musical community in Palestine. Although she was responsible for saving many thousands of young Jewish lives through the Youth Aliyah, Freier’s efforts were not officially acknowledged until 1975.

By founding the Youth Aliyah (Jugend-Alijah) in Berlin, Germany in 1932, Recha Freier saved thousands of Jewish lives. She was a multi-talented woman, a poet and musician, a teacher and social activist. However, in most accounts of the Holocaust she has either been underestimated or totally unacknowledged.

Early Life & Education

Recha Schweitzer was born in Norden (East Friesland), a small town in northeast Germany, on October 29, 1892, to Orthodox parents—Bertha (née Levy, 1862–Theresienstadt, 1945) and Menashe Schweitzer (1856–1929), both of whom were teachers. Her mother taught French and English, while her father taught a variety of subjects at a Jewish primary school. The family members were musical and Recha played the piano.

At a very young age Recha Schweitzer encountered antisemitism in her hometown, in the form of a notice in the local park which stated that “Dogs and Jews are forbidden.” In 1897 the Schweitzer family relocated to Silesia. There, Recha Schweitzer was tutored at home for some years before attending a lycée in Glogau, where most of the pupils were the daughters of officers. Once again she was confronted with antisemitism. Forbidden to write on the Sabbath, she was mocked by her classmates. The distress she felt as she grasped the import of this response influenced her whole life and made her an ardent Zionist.

Recha Schweitzer next attended a private gymnasium [high school] in Breslau where she completed the four-year curriculum in half a year. In 1912 she received permission to study at a university and simultaneously completed the examination for teachers of religion. As a graduate student she studied philology at universities in Breslau and Munich.

In 1919 Recha married Rabbi Dr. Moritz Freier (1889–1969), whom she had met in Breslau, where they also began their married life. They soon moved to Eschwege, where her husband was already a rabbi. Here, their first son, Shalhevet, was born in 1920. From 1922 to 1925 her husband served as a rabbi to the Jewish community in Sofia and while there she taught at a German high school. In 1923 their second son, Ammud, was born, followed in 1926 by a third son, Zerem. In 1929 the couple welcomed a daughter, Ma’ayan. In 1925 the Freier family moved to Berlin, since Moritz had been hired by the Jewish community of Berlin to officiate as rabbi at three synagogues: Rykestrasse (Prenzlauer Berg), Heiderreutergasse (Alte Schul) and Kaiserstrasse. In addition to being a busy young wife and mother, Recha worked as a writer and folklorist.

Establishing Youth Aliyah

In 1932, which became a decisive year for her, it became clear to Recha Freier that Jewish teenagers had no future in Germany, where they were being denied the right to professional training and employment. That year her husband had asked her to help five teenage boys who complained that they could not find any work because they were Jews. Wanting to help them, she first turned to the Jewish employment agency. Here, all that the counselor could do was recommend that she be patient, since a solution would surely turn up. One night an idea came to her: the boys should go to Palestine to be trained in workers’ settlements as agricultural pioneers. The boys enthusiastically agreed to this plan. As a result of this experience, the idea for the Youth Aliyah occurred to Recha Freier one year before the Nazis took power.

The difficulties her concept encountered from all sides were immense. Both Jewish organizations and parents were skeptical about the plan to send children alone to a distant country. Nevertheless, in January 1933, in Berlin, Recha Freier founded the Committee for the Assistance of Jewish Youth (Hilfskomitee für Jüdische Jugend), which provided the organization and support necessary to make the Youth Aliyah from Germany a reality. Offices were later opened in Jerusalem and in London.

Recha Freier traveled widely to publicize her idea and raise funds. She also contacted Henrietta Szold and the labor movement in Palestine. She asked Szold, the founder of Hadassah, to take over responsibility for the teenagers arriving in Palestine from Europe. Although Szold was initially of the opinion that the plan was not feasible, she ultimately agreed to become the director of Youth Aliyah’s Jerusalem office and to coordinate accommodation for the young people in Palestine. As a result, she was frequently (and incorrectly) assumed to be the founder of the Youth Aliyah.

Due to the clash between their very different personalities, these two valiant women rarely met. Despite their common goals, Recha Freier was repeatedly rebuffed when she tried to speak with Henrietta Szold. Neither the strong resistance that Recha Freier’s idea initially encountered nor the many subsequent difficulties and misunderstandings that beset her remarkable program prevented thousands of German teenagers from leaving Germany for Palestine in the next few years, thus saving their lives. As the modes of persecution of Jews became more severe under Nazi tyranny, and as hope for political change faded, the objectives of the Youth Aliyah received increasing recognition from Jewish organizations in Germany.

Life in Nazi Germany

Recha Freier resisted fleeing from Germany as long as the possibility of rescuing Jews remained. Her son Shalhevet had left for England in 1937. Moritz Freier followed in 1938 with their other sons. Recha and her husband, who had been separated for a long time, never again lived together. In 1949 Moritz Freier took up a post as rabbi of the Jewish community in Berlin, and ultimately retired to Zurich where he lived until he emigrated to Israel in 1967, two years before his death.

After September 1939 Recha Freier tried to rescue Polish Jews who were considered “enemies of the state” in Nazi Germany and who were treated with extreme cruelty in concentration camps. Unafraid of using illegal means to help the Polish men, she succeeded in getting some of them out of the concentration camps, helping them to go on to Palestine. Noble as her intentions were, this additional effort to rescue yet another group was the prelude to a conflict with both the Palestine Office and the Reich Association of Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland). Eventually she was suspended from all her functions in the Youth Aliyah.

Work in Yugoslavia

After she was banned by the Palestine office of Youth Aliyah in 1940, Recha Freier had to leave Nazi Germany. She fled to Yugoslavia with her eleven-year-old daughter. They remained for a while in Zagreb, hoping to be able to organize the emigration of German Jewish children from there. Recha Freier thought that if she and her daughter had been able to cross the Yugoslavian border illegally, this must also be possible for other young people. She therefore turned to the Reichsvereinigung as well as to friends, WIZO members and the Jewish community in Zagreb, with a plea to initiate the transportation of children to Vienna, whence they would be smuggled over the border into a safe country. Since the Association was unwilling to cooperate, no Jewish children arrived in Vienna to test Recha Freier’s latest scheme to save them.

“So I had to do something,” recalled Recha Freier. “In desperate situations I was afraid of nothing, not even trickery and lies. I sent a telegram to Berlin: ‘Hundreds of immigration certificates lay here and if the children do not come, I will make a world-wide scandal of the situation.’” This proved effective. A little later, smugglers brought the first group of German children to Zagreb. These children were the orphans of fathers who had been killed in concentration camps. In the next few weeks one hundred and twenty children and teenagers arrived. It was almost certain that they would be sent to a concentration camp if they were to return to Germany.

While awaiting the opportunity to leave Yugoslavia for Palestine, the children were housed with Yugoslavian Jewish families. After eighty certificates arrived, eighty children traveled to Palestine. The remaining forty eventually reached Switzerland, where they remained till the end of the war.

Involvement in the Music Community in Palestine/Israel

Recha Freier and her daughter had left a month earlier for Istanbul, where a certificate awaited them. They then proceeded to Syria and arrived in Palestine in March 1941. Although Recha Freier wanted to continue her work for the Youth Aliyah, the differences with Henrietta Szold prevented this. Szold told her that there was no position open for her anywhere within the organization in Palestine.

Recha Freier thus withdrew from the Youth Aliyah and founded the Agricultural Training Center for Israeli children. She also pursued her activities in community work and as a writer.

In 1958 Recha Freier established The Israel Composer’s Fund to encourage musical creativity by commissioning works from local composers, who had to eke out a living by giving private lessons, instead of devoting their time and talent to composing. By 1968 some fifty compositions had been commissioned. In 1966 she founded the Testimonium, together with the avant-garde composer Roman Haubenstock-Ramati (1919–1994), who wished to create an artistic framework comparable to the Passion, the subject of which would be Jewish suffering. Recha Frier expanded the concept to include Jewish faith and heroism throughout history.

In 1968 the Testimonium gave its first performance—Jerusalem: A Pageant of Three Thousand Years of History—in David’s Citadel in the Old City of Jerusalem, which was put at Freier’s disposal by courtesy of the then Mayor of Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek. A total of six Testimoniums were performed between 1968 and 1983 (see selected works).

Conductor Gary Bertini (1927-2005) wrote that “The Testimonium … has broken through the accepted forms of the concert … by disbanding existing definitions [of a concert] and creating a combined concert-theater-musical and recital.”

Receiving Recognition

In her later years Freier occasionally felt bitter that her earlier work for the Youth Aliyah was never properly recognized and that Henrietta Szold was mistakenly considered its founder. It was not until 1975, when she was eighty-three, that her work was acknowledged by the award of an honorary doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem for her idea of “organized transport of youth into kibbutzim.” Now at last, she was celebrated as one of the “most commendable Zionists.” In 1981 she received the Israel Prize in acknowledgement of her special merits.

Recha Freier died in 1984 in Jerusalem. In November of that year the City Council of Berlin-Charlottenburg affixed a commemorative plaque at the Jewish Community Center in Fasanen Street honoring “Recha Freier, the Founder of Youth Aliya.” In 1990 the Recha Freier Educational Center at Kibbutz Yakum near Herzliyyah in Israel was founded in her honor.

Selected Works

Arbeiterinnen erzählen, Berlin: Kedem, 1935.

Auf der Treppe. Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag, 1976.

Fensterläden. Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag, 1979.

Let the Children Come: The Early History of Youth Aliyah. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1961.

Testimonium: I Jerusalem (1968); II The Middle Ages (1971); III De Profundis (1974); IV Lucem cum Fulgeret (If ever I saw the light shining, Job 31:26) (1976); V Trial 19 (Spanish Inquisition) (1979); VI From the Revealed and From the Hidden (1983).

Recha Freier wrote or arranged texts for many works which were performed in The Testimoniums.

Allgemeine Jüdische Wochenzeitung, (April, 27 1984): 6.

Allgemeine Jüdische Wochenzeitung, (May 16, 1992): 12.

Asaria, Zwi. Die Juden in Niedersachsen. Von den ältesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart. Leer: Rautenberg, 1979: 296, 664 (picture).

Erel, Schlomo. Neue Wurzeln. 50 Jahre Immigration deutschsprachiger Juden in Israel. Gerlingen: Bleicher, 1983, 134–145.

Encyclopedia Judaica, 7, (1971): 134.

Feidel-Mertz, Hildegard. “Freier, Recha.” In Jüdische Frauen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. Lexikon zu Leben und Werk, edited by Jutta Dick and Marina Sassenberg, 125–126. Reinbek bei Hamburg: 1993.

Freier, Shalheveth. “Recha Freier and the Testimonium.” Israel Music Institute News (1991/4–1992/1): 2–6.

Gelber, Yoav. “The Origins of Youth Aliyah.” Studies in Zionism. Vol. 9, (3, Autumn 1988): 147–171.

Gill, Dominic. “Testimonium in Israel.” Financial Times London, (March 17, 1983), 19.

Gödeken, Lina. Das Ende der Juden in Ostfriesland. Aurich: Ostfriesische Landschaft, 1988, 60.

Griver, Simon. Recha Freier—Youth Aliyah’s Unsung Heroine Jerusalem: 1984.

Haag, John. “Recha Freier.” In Women in World History. A Biographical Encyclopedia, Vol. 5, Waterford: 2000, 767–770.

Jüdische Wochenschau [Lasemana Israelita], (April 3, 1984): 5.

Kova, Oda. “Recha Freier: The Dreaming Woman.” In Sie flohen vor dem Hakenkreuz, edited by Walter Zadek, 93–99. Reinbek bei Hamburg: 1981.

Levin, Marlin. “The Foundation of Youth Aliya.” Jerusalem Post. (November 28, 1995), 6.

Luft, Gerda. Heimkehr ins Unbekannte. Eine Darstellung der Einwanderrung von Juden aus Deutschland nach Palästina vom Aufstieg Hitlers zur Macht bis zum Ausbruch des Zweiten Weltkrieges 1933–1939. Wuppertal: Hammer, 1977.

Maier, Hugo. Who is who der Sozialen Arbeit, Freiburg i. Br.: Lambertus, 1998, 179–180.

Maierhof, Gudrun. Selbstbehauptung im Chaos. Frauen in der Jüdischen Selbsthilfe 1933 bis 1943. Frankfurt/Main: Campus Verlag, 2002, 221–234 and 329–330.

MB-Mitteilungsblatt des Irgun Olej Merkas Europa, (July 25, 1975): 4.

Ogorek, Monika, Recha Freier und die Gründung der Jugend-Alijah. Porträt einer ungewöhnlichen Frau, feature for the SFB, Berlin: 1986.

Portrait, Ruth. “Youth Aliyah’s Mother.” Jewish Observer and Middle East Review (December 3, 1971), 14.

Rosenkranz, Herbert. “Recha Freiers Testimonium. Die neue Hochschule. Zeitschrift für anwendungsbezogene Studiengänge, 35 (1983): 382.

Rosenkranz, Herbert. “Recha Freier.” Das neue Israel (May 1984): 29.

Schoppmann, Claudia. “Recha Freier.” In Zwischen Rebellion und Reform. Frauen im Berliner Westen, edited by Birgit Jochens and Sonja Miltenberger, 50–52. Berlin: 1999.

Voigt, Klaus. “I ragazzi di Villa Emma in Nonantola.” In La comunità ebraiche a Modena e a Carpi, edited by Franco Bonilauri and Vincenza Maugeri, 241–265. Florenz: 1999.

Voigt, Klaus. Villa Emma. Jüdische Kinder auf der Flucht. Berlin: 2002.

Walk, Joseph. Kurzbiographien zur Geschicthe der Juden 1918–1945, München/New York/London/Paris: De Gruyter, 1988, 99.

ArchivesCentral Zionist Archives, Jerusalem: Recha Freier Collection.

Kibbutz Yakum, Herzliyyah, Israel: Recha Freier Collection.

Landesentschädigungsbehörde, Berlin, Germany: Restitution File.