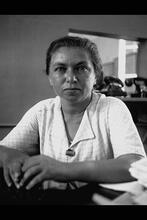

Chava Slucka-Kesten

Chava Slucka-Kesten began her career teaching in Warsaw before World War II and kept teaching during the war in Moscow. During this time, she was also a part of the Warsaw Zionist socialist party, and she continued her political participation after her postwar move to Tel Aviv, where she was an active member of the Communist Party of Israel (MAKI) until her death. Slucka-Kesten’s writing reflected her life, and her prolific career included articles on pedagogy, literary criticism and politics, short stories and children’s stories. Writing from the perspective of a politically engaged woman, Slucka-Kesten offers a unique glimpse into pre- and post-war Jewish life in Poland’s cities and villages, as well as into the early years of the State of Israel.

Early Life

Born in Warsaw, Poland on December 24, 1900 to an impoverished working-class family, Chava Slucka-Kesten (also spelled Chawa Slucka-Kestin; Khave Slutski-Kestin; Yiddish סלוצקא-קעסטין, חוה, transliteed Khave Slutska Kestin,) managed to receive both Jewish and secular academic education. She earned a master’s degree in history and pedagogy at the University of Warsaw in 1939, a rare accomplishment for a Jew and a woman. While she pursued her studies in Warsaw, she managed to work as a researcher in the Tsemakh Shabad program at YIVO (the Institute for Jewish Research) in Vilna and graduated from the Jewish Teachers’ Seminary in Warsaw, where she later became an instructor. Slucka-Kesten taught at secular schools under the auspices of socialist parties such as the Bund and the Borokhov parties and also founded a school for developmentally handicapped children. Throughout this period, she was active in the cultural section of the Po’alei Zion, the Zionist socialist party in Warsaw.

World War II and Later Life

When the Germans overran Poland in 1939 Slucka-Kesten escaped to the Soviet Union, where she was able to continue her teaching career. In 1946, after the war, Slucka-Kesten returned to Poland where she taught at the Jewish Teachers’ Seminary and was an active member in the Central Committee of Polish Jewry. From 1950 to her death on March 1, 1972, Slucka-Kesten lived and wrote in Tel Aviv as an active member of the Communist Party of Israel (MAKI). A surviving daughter lives in Israel.

Literary Content and Style

As a writer from the perspective of a politically engaged woman, Slucka-Kesten offers a unique glimpse into pre- and post-war Jewish life in Poland’s cities and villages, as well as into the early years of the State of Israel; there are few such women’s voices.

In Shef un rinder (Sheep and Cattle) she uses the form of the memoir to describe pre-Holocaust Jewish (Yiddish) Small-town Jewish community in Eastern Europe.shtetl life through the eyes of a sophisticated and educated Jewish woman. As in the writing of many women, her focus is on the intimate and the familial. Such descriptions and reports are rare, as we know from the dearth of available women’s writing and the areas of Jewish life they illuminate. So also, with Slucka-Kesten; most of her writings are lost but what remains helps to flesh out a literature of women’s lives and women’s sense of events, differing in both subject matter and tone from the literature with which we are familiar.

Her description in the aforementioned book lovingly portrays the common Jewish practice in nineteenth-century Europe, of children raised by grandparents. In Slucka-Kesten’s case, as was generally true, this was due to extreme poverty. Besides the generational gap we also see an emerging secularist socialist girl growing within a religious conservative home, and the tolerance that love and warmth afforded. We have a model of a woman caught in the cataclysmic changes of Jewish life at that time, who reacts by embracing change. She pursues education and a career.

Slucka-Kesten’s stories of early Israeli life also afford unique perspectives due to her focus on the lives of women who are not part of the Zionist discourse of those years. An example is “Her Story,” in which the taboo subject of Moslem-Jewish intermarriage and racism are discussed.

Her writing style is direct and her presence as narrator evident. Her Yiddish is accessible and inviting. Although not interesting stylistically, Slucka-Kesten’s writing is significant both sociologically and in terms of gender studies. It offers an alternate model from the passive, home-centered portraits often presented to us.

Publications

Chava Slucka-Kesten’s writing reflected her life and covered a wide spectrum. She wrote articles on pedagogy, literary criticism and politics, short stories and children’s stories. Although the Yiddish Lexicon cites numerous political articles—in such magazines as Arbeter Tsaytung (Workers’ Times), Der Yunger Dor (New Generation) Warsaw, Vilner Tog (Vilna Daily) and YIVO Bleter (YIVO Letters) from Vilna, Arbeter Vort (Workers’ Words) and Dos Nayeh Lebn (The New Life) in Łódź, Ney Velt (New World) in Shvel, Arbiter Tribuneh (Workers’ Tribune), Kol Ha-Am (Voice of the Nation), Fray Yisroel (Free Israel) from Tel Aviv and Sovietishe Heimland from Moscow none of them are available.

Her two books of short stories which are known to date are In Undzere Teg: dertseylungen, miniaturn un skitsen (In Our Time: Stories, Miniatures and Sketches), published in Tel Aviv in 1966, and Shef un rinder. Some chapters of an unfinished novel were published in Fray Yisroel, Tel Aviv.

“Bread.” Rasskazy izrail'skikh pisateleĭ; perevod s ivrita i idish. Moscow: Progress, 1965.

"Shul-yontoyvim in lebn un in psikhik fun kind" (School holidays in the life and psyche of a child)." Yivo-bleter, vol. 12 (1937): 474-84.