Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle

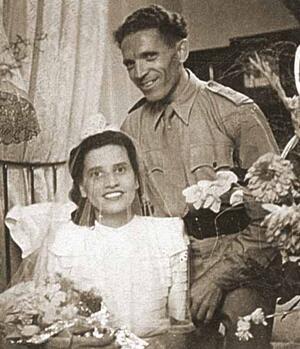

Born in 1916, Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle’s family was part of an established Sephardic community of Salonika, Greece. Life changed drastically after the Nazi invasion in 1941. Bouena joined the Red Cross and began describing her experiences in her Ladino poetry. She had violent confrontations with the leader of the Jewish collaborators; he had her fiancé shot to death on Bouena’s wedding day. After being put in prison, a friend helped Bouena flee. She joined the partisans, serving first with Loyalists and later with Communists. Bouena saved many children, smuggling them into Turkey and Palestine. In June 1945, she returned to Greece on an undercover assignment to set up an underground railroad to Palestine for survivors. In 1946, she married Max Garfinkle and a year later they moved to Montreal, where she wrote her memoirs.

Bouena Sarfatty Garfinkle was a highly unusual woman whose devotion to her community during World War II led her to activities no other Sephardi woman dared undertake. At a later stage in her life, her historical-literary acumen enabled her to record Jewish life in Salonika during the twentieth century, including the Nazi conquest and the devastation of this community. Her courage and insights led to the saving of lives as well as to recording her heritage in Ladino.

Family & Early Life

Bouena (Tova) Sarfatty was born on November 15, 1916 in Salonika, Greece to a family of descendants of exiles from Spain which was established and well-respected in the Sephardic community. After the death of her father, Moise (ca. 1919), Bouena’s older brother Eliahu took on the responsibilities as head of the family and cared for their mother Simha, their maternal centenarian grandmother Miriam, the three older girls (Rachel, Daisy, Marie), Bouena and the youngest, Regina.

All of the girls were educated; some studied at the local Alliance Israélite Universelle school while others also attended the Italian school. Bouena spent some time in Marseille studying with a couturier and living with her sister Marie, who had moved there before World War II. Bouena was fluent in French, Ladino, and Greek (which was unusual) and her linguistic abilities are reflected in her writings.

Pre-war Salonika was a bustling and exciting place for a young Sephardi woman. Debutante balls were part of the social world of the high society, and Bouena was presented at the age of eighteen. The family, especially Eliahu, was involved with Zionist organizations such as the Keren Hayesod until the Nazi invasion in April, 1941. At this time, however, life changed drastically for all the Jews of this northeastern port city. Bouena, her sisters and friends immediately volunteered for the Red Cross, helping the Gifts for the Poor organization in distributing soup to the hungry. In July, 1942, the Nazis began to conscript the young Jewish men into forced labor.

Salonika During the War

Family Portrait, 1937. L to R, back row: Marie (Miriam, older sister of Bouena), Eliahu (older brother), Rachel (older sister); front row: Regina (younger sister), Bouena, Henrietta (daughter of Marie), Alice (daughter of Marie), Simha (Bouna's mother), Daisy (Desica, daughter of Rachel).

Courtesy of Dr. Eli Garfinkle

Bouena recorded Ladino proverbs during the war and composed hundreds of verses in Ladino that reflected the everyday trials and tribulations of the conquered community. Because of her Red Cross work, she had contact with the young men in the labor camps and often brought news to the anxious mothers and relatives—no easy task, since many of the men starved to death. She and her sister often brought bread and water to the POWs who were marched past their home daily; when they noticed a mezuzah on the chest of a wounded British prisoner, they decided to act. The family sneaked him into their home, washed and dressed his wounds, but unfortunately their English patient died of fever. The subsequent clandestine burial in the dead of the night was dangerous for the entire community, but fortunately went unnoticed; all these experiences are described in Ladino poetry (coplas). Her family still has the mezuzah.

Bouena had confrontations with the leader of the Jewish collaborators, Vital Hasson; as a demonstration of his strength, he beat Bouena and forced her to drink such large quantities of the powdered milk that she was preparing for needy infants that she became ill. Her poetry and memoirs frequently refer to Hasson and his hooligans, who forced Bouena’s close friend Sarah Trabout to marry Hasson’s brother against her will; Sarah cried throughout the ceremony but was aware that her family would suffer severely if she refused. Hasson also took revenge on Bouena by informing the Nazis that her fiancé, Hayim, had escaped from his forced labor group. He was shot to death on their wedding day—a tragedy that would haunt Bouena for years.

Fleeing Home

While hiding and arranging to flee, Bouena was arrested and placed in the Pablo Mela prison in the local Nazi headquarters. A rescue was arranged, whereby a partisan dressed as a German officer arrived with instructions for her release. After the war, Bouena sought out her savior, only to discover that her female German prison guard later recognized the masquerading officer and had him tortured and killed. The escaped prisoner had no choice but to flee, aided by her Belgian friend, Georgette Modiano, who procured an Italian passport for her. Just before her departure, she received a packet, apparently from her brother, that contained jewelry wrapped in lingerie. Bouena, her face covered by a veil, was certain that she saw Hasson at the station as she boarded a train, but for some reason he did not turn her in.

After Bouena joined the partisans, she was known as Maria (Maritsa) Serafamidou of Comotini in northeastern Thrace. She served first with the Loyalists and then with the Communists, but she became ill and her contact was killed. One of her tasks was to gather information while posing as a cook in a German kitchen; the commandant was captured and delivered by her to a British submarine for interrogation in England. Later, she saved many children, smuggling them to Turkey and to Palestine, helping the wounded and pregnant she found en route, and risking her life time after time. Her accomplishments were so outstanding that a film was made about her in post-war Greece.

Return to Greece & Post-War Life

In June 1945 she returned to Greece, ostensibly as a dietician for the Palestinian Jewish Relief Unit of the UNRRA soup kitchens for refugees from the camps, but in reality as an undercover agent assigned to set up an underground railroad to Palestine for survivors. She remained in Salonika after she had completed her mission in order to learn the fate of her family and its possessions, and helped many survivors. Her brother, sister Regina, grandmother and aunts had died in Auschwitz. Before the deportation, Eliahu had distributed their possessions to various friends and neighbors; when confronted, most of them were antagonistic and hostile to Bouena. Somehow she managed to find a home in the country from which she recovered her trousseau, which included needlework, tapestries, linens and other handiwork and family furniture.

In 1946, Bouena married Max Garfinkle who had served as quartermaster for the relief unit and was also working for the Jewish underground; he convinced her to try life at his A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz, Ein ha-Shofet, but the experience was too bitter a pill to swallow. There was little compassion offered to the non-Ashkenazi outsider who had stolen the heart of one of their founders, despite or perhaps because of the fact that she had sewing and embroidery talents of the highest order. In 1947, they moved to Montreal, where she wrote her memoirs. Bouena died on July 23, 1997 and was survived by her son and daughter-in-law, Drs. Ely Garfinkle and Linda Dansky, and four grandchildren. She is remembered as a master of needlepoint and a feisty survivor-partisan-heroine of the decimated but once vibrant Salonikan Jewry.

Ben, Yosef. Greek Jewry in the Holocaust and the Resistance, 1941–1944 (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Institute of the Saloniki Jewry Research Center, 1985

Levine Melammed, Renée. “The Memoirs of a Partisan from Salonika,” Nashim 7 (2004): 151-73.

Levine Melammed, Renée. An Ode to Salonika: The Ladino Verses of Bouena Sarfatty. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993

Molho, Michael and Yosef Nehama. The Destruction of Greek Jewry, 1941–1944 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1965

Naar, D.E. Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Recanati, David A., ed. Remembering Salonika: The Glory and Destruction of the Jerusalem of the Balkans, 2 vols. (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: N.p., 1952

Refael, Shmuel. “The Holocaust in the Poetry of Bouena Sarfatty of Salonika (Hebrew). In The Languages and Literatures of the Spanish and Oriental Jews, edited by J. Bentulilla, D. Bunis and E. Hazan, 128-141. Jerusalem: The Bialik Institute, 2008.

Rivlin, Bracha. Pinkas Hakehillot: Greece (Hebrew). Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1998

Rivlin, Bracha. Salonika: Mother City of Israel (Hebrew). Jerusalem: N.p., 1967.

Levine Melammed, Renée. “The Memoirs of a Partisan from Salonika,” Nashim 7 (2004): 151-73.

Levine Melammed, Renée. An Ode to Salonika: The Ladino Verses of Bouena Sarfatty. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Naar, D.E. Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Refael, Shmuel. “The Holocaust in the Poetry of Bouena Sarfatty of Salonika (Hebrew). In The Languages and Literatures of the Spanish and Oriental Jews, edited by J. Bentulilla, D. Bunis and E. Hazan, 128-141. Jerusalem: The Bialik Institute, 2008.