Tosia Altman

Tosia Altman grew up in Lipno, Poland, among a warm Jewish community. She learned Polish and Hebrew and was an active member of the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir youth movement. The outbreak of World War II derailed Altman’s plans to make Aliyah, and instead she became a spy for Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir and went back into German occupied Poland. A fearless leader in the Jewish clandestine resistance to the Nazi occupation, Altman played an integral role in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising on April 18, 1943. Altman died a few months later in the custody of the Germans, after a fire in the attic in which she was hiding badly injured her.

Childhood in Poland

Tosia (Taube) Altman was born on August 24, 1919, to Anka (Manya) and Gustav (Gutkind) Altman, in Lipno, Poland. She grew up in Wloclawek, where her watchmaker father ran a jewelry and watch store. A Zionist (of the General Zionist stream), her father stood out as a dedicated, welcome participant in the institutions of the local Jewish community.

A warm, open and broad-minded cultural atmosphere marked the family home. Altman learned Polish and Hebrew and was noted for her gift for languages and love of reading. The Hebrew gymnasium and the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir youth movement were major ideological influences in her life. Altman was known as a talented youth-group leader, committed to the movement and its values. She was elected to the leadership of the local branch, which sent her as a delegate to the Fourth World Convention of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir in 1935. This was a powerful and moving experience for her. She joined the hakhsharah (training) A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz at Czestochowa in 1938, but was soon placed in charge of youth education for the central leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir in Warsaw, causing her Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah to be postponed.

Impact of WWII

With the outbreak of war and the announcement of the evacuation of Warsaw (September 7, 1939), an appeal was issued for members of the youth movements to move eastward. Together with Adam Rand (of the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir leadership), Altman made her way, mostly on foot, to Rovno, amid fleeing refugees and aerial bombings. There, members of the leadership and numerous young people had gathered to consider their next move. The entry of the Soviet army into eastern Poland confronted the members of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir with the dilemma of choosing between Zionism and Communism. To avoid this, they continued fleeing towards Vilna, which was not yet under Soviet control, hoping to carry out their aliyah from there. Members of the pioneer youth groups from throughout occupied Poland now gathered in Vilna, Lithuania, together with their leadership. They set up a central headquarters that immediately launched a series of ultimately unsuccessful attempts to immigrate illegally to Palestine.

Mission to Nazi-Occupied Poland

The leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir in Vilna was extremely concerned with the fate of the movement’s members who were left behind under German occupation without their youth-group leaders. As a member of the central leadership with the appropriate personality and appearance, Altman was instructed to return to the Generalgouvernement (Nazi-occupied Poland). Although she had family members in Vilna and had only begun to recover from the hardships of her recent journey, Altman accepted the mission. She was the first to return to occupied Poland (followed later by Josef Kaplan, Mordecai Anielewicz and Samuel Braslav). After two failed attempts to cross both the Soviet and German borders, she finally succeeded. Altman began to gather the remaining youth-group leaders and organize the movement’s branches. With the arrival of additional members, Altman began to make the rounds of other cities, despite the fact that Jews were prohibited from traveling on trains. In every city she reached, she encouraged the young people to engage in clandestine educational and social activity. In Warsaw, a leadership emerged that coped as best as possible with the life-and-death problems of the young people. Attempts were made to establish training A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim and collectives and to publish a newspaper. Altman corresponded with the leadership in Vienna (Adam Rand), the movement in Palestine and emissaries in Switzerland (Nathan Schwalb and Heine Borenstein). The correspondence was written in code for fear of German censors.

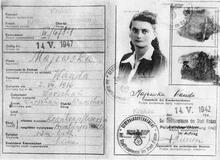

The ghettoization of the Jewish population of Warsaw and its environs (November 1940) made her travels even more difficult. Her blonde hair and fluent Polish were no longer enough; with every trip, she risked death. Forged papers, outdated documents and stamps, and the danger of Polish informants who “sniffed out” Jews were all a constant peril. But Altman continued to travel to the cities of Galicia, to the Zaglebie region (1941) and to Czestochowa, her visits serving as a source of strength and encouragement to the young people.

Following the German invasion of the Soviet Union (June 22, 1941), contact with the movement in Vilna was cut off and the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir leadership in Warsaw saw itself as responsible for the entire movement. Rumors began to arrive of the massacre of Jews in Ukraine, Serbia and Lithuania, described as “pogroms.” Without contacts or information regarding identity papers, Altman traveled to Vilna (after a youth Polish scout, Henryk Grabowski, had returned with reports of systematic slaughter). She arrived in Vilna following an arduous journey, apparently on December 24, 1941. She entered the now-reduced ghetto area, together with Haika Grosman, on Christmas Eve. At a gathering of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir members she recounted the desperate living conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto and the thriving movement that existed there in spite of everything. To the members of the central leadership, she proposed a return to Warsaw to save the activist core for the sake of the movement, but left the decision in their hands. They refused, for a heartrending reason—they felt responsible for the young people; moreover, there was simply no place to run. In the view of Abba Kovner, the slaughter was not local in nature; its aim was the total extermination of the Jewish people. Altman was told that a decision had been taken among the leadership of the various youth movements in Vilna that the Jews should not go to their deaths without a fight (“Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter,” in the words of the manifesto composed by Abba Kovner). Altman absorbed and internalized the spirit of resistance. (She may also have delivered the manifesto before Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir members).

Polish Resistance

Before returning to Warsaw, she managed to visit Grodno and other cities in eastern Poland. She returned to her comrades with a clear message: the Jews were being slaughtered systematically, and they must resist. In Warsaw, it was difficult for them to accept that the catastrophe would reach them. But they soon received confirmation, in the form of information on the Chelmno death camp in the Generalgouvernement. Some time later (March 18–26), the mass deportation from Lublin to Belzec began. As part of the self-defense effort in Warsaw (March 1942) the leaders of the Leftist parties (Communists, Left Po’alei Zion, Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir and Dror He-Haluz) organized an anti-fascist bloc aimed at recruiting young people to the partisans’ struggle, aided by Polish Communists and Soviet weapons. The bloc, which received no arms or assistance, soon fell apart.

Altman continued traveling to the ghettos of Poland, laying the groundwork for resistance among the youth. But she witnessed firsthand the destruction of Polish Jewry. In her final letter to Palestine, from Hrubieszow (dated April 7, 1942), she wrote of being tortured by the sight of the destruction yet unable to help: “Jews are dying before my eyes and I am powerless to help. Did you ever try to shatter a wall with your head?”

With the first wave of mass deportations from the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka (July–September 1942), the Jewish Fighting Organization (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or ZOB) was established, following negotiations with the heads of the socialist and Zionist parties. Altman, a member of the central leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, was sent to the Aryan side to make contact with the Polish underground Armia Krajowa (AK) and the (Communist) Armia Ludowa in order to obtain weapons and support. Their contribution was minimal, but Altman and other women managed to bring in hand grenades and additional arms obtained at great risk.

Worsening Conditions in Poland

On September 3, 1942, the leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir in the ghetto lost two of its key members, Josef Kaplan and Samuel Braslav, who were captured by the Gestapo. The weapons “cache” smuggled in by a young woman was also uncovered. Compounding the blow was the harsh Aktion carried out that month using the kociol (cauldron) method, whereby Jews were lured out of hiding, entrapped in a small area, and deported to the death camps. Of the ghetto’s six hundred thousand Jewish inhabitants, only fifty to sixty thousand remained alive. Altman was joined by Arie (Jurek) Wilner in order to hasten the acquisition of weapons. She continued her travels to the various ghettos, now as an emissary of the ZOB. At times she managed to save young men and women from being deported to their deaths. She journeyed to Cracow to organize cooperation with two underground groups: He-Haluz ha-Lohem and the Iskra (Spark) fighting organization, a group similar to Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, operating with the aid of the PPR (Polska Partja Robotnicza, or Polish Workers Party). These two organizations were in fact responsible for the greatest success of the Jewish fighting effort in Cracow.

On January 18, 1943, an additional Aktion was carried out in the Warsaw Ghetto. Altman returned to the ghetto at this point. The ZOB units were scattered, as were the weapons. There were pockets of spontaneous resistance here and there, in the form of shooting from various buildings. Anielewicz, commander of the ZOB, together with a party of his fighters, mingled with the masses awaiting deportation and attacked German troops. Though injured, he miraculously survived. Most of his ZOB comrades were killed in this action. A number of others, including Tosia Altman, were captured during the ensuing round-up. Taken to the Umschlagplatz, Altman was rescued by a member of the Jewish police who was acting on behalf of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir.

Despite the sense of defeat, a new plan of resistance arose, which entailed dividing the ghetto into sections, distributing weapons and creating separate fighting units. The ZOB played a major role in this process. The remaining Jews in the ghetto began to build bunkers. The January revolt led to a change in the attitude of the Polish underground (AK), which provided a small amount of weapons to the Jewish underground. The remainder were obtained by Altman and Wilner from criminal elements who traded in arms. In March 1943 Wilner was caught by the Gestapo and brutally tortured, but he did not betray any of his comrades. He was somehow saved by the young Pole, Henryk Grabowski, and brought back, injured and sick, to the ghetto. Altman also returned to the ghetto, for fear that her whereabouts had been discovered. Yitzhak Zuckerman was sent to act as liaison with the Polish underground.

Ghetto Revolt

On April 18, 1943, the ghetto was surrounded by the German gendarmerie and the Polish police. The final Aktion began—and the revolt erupted. Altman reported on the first day’s successes by telephone (from a German manufacturing plant in the ghetto) to Zuckerman on the Aryan side. Her role in the ZOB command remained, as before, to relay messages and information. On the third day, the Germans began to systematically set fire to the buildings of the ghetto. Anielewicz and his command moved to a bunker at 18 Mila Street, with Altman serving as liaison between him and the bunker of the wounded, where Wilner was located. When the situation worsened, Wilner was moved to Mila 18. Altman went out on rescue missions to retrieve fighters trapped in the burning sections of the ghetto.

Fighting continued at night, but the burning buildings made it difficult to exit the bunkers. It was only then that the idea arose to smuggle the fighters to the Aryan side by way of the sewers. One group made its way out. A second group were about to leave, but were waiting for their contact. In the bunker at Mila 18, where Anielewicz and his men had relocated, some three hundred people were huddled together under impossibly crowded conditions. From there as well, scouts were sent to check out escape routes.

On the twentieth day of the fighting, May 8, 1943, the bunker was discovered by the Germans, who piped gas into it to force out those in hiding. When camouflaged openings were discovered, additional gas was piped in. Wilner called upon his comrades to take their own lives and most of them, including Anielewicz, did so when they could no longer fight off the gas. A few lone fighters, six in number, were able to reach another concealed opening. They were found at night by Zivia Lubetkin and Marek Edelman, injured and suffering from the gas. Among the survivors was Altman. Sick, wounded and exhausted, she escaped from Zivia Lubetkin’s bunker via the sewers together with a group of fighters. On the Aryan side, she was housed with several comrades in the attic of a celluloid factory. To gain entry they used a ladder, which was later removed to prevent the discovery of their hiding place.

On May 24, 1943, as the result of a terrible accident, fire broke out in the attic and spread rapidly. A few comrades managed to escape. Altman, who was badly burned, tried to jump out but collapsed, her entire body in flames. The Polish police handed her over to the Germans, who transferred her to hospital. There she died untreated (apparently on May 26, 1943), wracked with pain and possibly tortured.

Tosia Altman, the first of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir’s leadership to answer the call, was the last to fall.

The tragedy was preceded by rescue attempts. In Palestine, it was felt that there was a need for a firsthand account. A Jewish community in Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel. "Old Yishuv" refers to the Jewish community prior to 1882; "New Yishuv" to that following 1882.Yishuv emissary posted to Turkey returned and demanded that his movement do everything possible to get Tosia Altman out of Poland. Altman, whose sole focus was the life-and-death struggle in the ghetto, was unaware of this, nor did she wish to be rescued.

Altman, who represented the Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir movement in the underground correspondence, was a symbol and a legend among the members of her movement in Palestine—a symbol that was quickly forgotten.

Gutman, Israel. The Jews of Warsaw, 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt. Translated by Ina Friedman. Bloomington, Indiana: 1982.

Shalev, Ziva. Tosia Altman: From the Leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir to the Command of the ZOB (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1992, 15–17, 268–274.