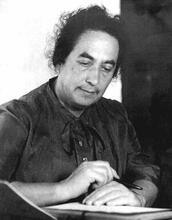

Barbara (Monique Andree Serf)

The singer, composer, and songwriter Barbara (Monique Andree Serf) in 1965.

Image courtesy of Jean Arkesteijn via Wikimedia Commons.

“Barbara” (the stage name of Monique Andrée Serf) was a French singer-songwriter whose Jewish identity influenced her music. Born in Paris in 1930, Barbara and her family hid in several different French cities throughout the German occupation. After the war, Barbara studied music in Paris, rising to fame in the 1960s after her initial debut in Brussels. Barbara was beloved in France due to her melancholy musical style, her pathos as a suffering artist, and her unique non-conforming attitudes. Barbara was public about her Jewish identity and her popular song “Göttingen” supported Franco-German reconciliation. She touched the hearts of the French people by singing “Children are the same in Paris and Göttingen. Oh, may the time of blood and hatred never return” and was honored posthumously for her work.

Early Life and Family

Under her simple stage name “Barbara,” Monique Andrée Serf (b. Paris June 9, 1930, d. Neuilly-sur-Seine November 24–25, 1997) was an immensely popular French singer and composer in the cabaret-style. As the French Yahoo encyclopedia puts it, she appeared as “a fragile woman, of dark sensuality, frail voice, and careful diction.” There was definitely something Piaf-like about her. She was born in the seventeenth arrondissement of Paris, the second child of fur salesman Jacques Serf, of Alsatian Jewish origin (b. Paris November 25, 1904, d. Nantes December 20, 1959), and Esther Brodsky, born in Tiraspol, Moldavia. During the German occupation, the family took refuge in several localities in France; in 1942 they had to flee from one of them, Tarbes, after they were denounced as Jews. In 1944, still under the occupation, the future “Barbara,” who would accompany herself on the piano, underwent the first of seven operations on her right hand.

After the war, she studied music in Paris, auditing courses at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique. In 1950, she ran off to Brussels for two years, where she was at first lodged by her cousin Sacha Piroutsky, a balalaika player, who became somewhat violent with her. It is there that she first appeared on stage under the name Barbara Brody. Back in France, on October 31, 1953, she married Claude Jean Luc Sluys (b. January 7, 1928); this union, lasting a few months, was not formally dissolved until November 12, 1962.

Rise to Fame and Death

Barbara became famous during the 1960s and has remained so, even now when she lies buried in the Bagneux cemetery, near Paris, in her mother’s family plot, under a gravestone displaying a star of David. (Her funeral service was described as “sober and secular” in Le Monde of November 29, 1997.) A sign of her enduring belovedness in France: the melancholy style for which she was known made it obvious that lyrics of one of her songs should be recited at a solemn event of national significance, the collective funeral for unclaimed victims of the summer 2003 extreme heatwave that killed thousands in France:

When those who are going go away,

When the last day has risen

In the blond light,

When those who are going go away

For always and forever,

Under the deep earth ...

Another indication of her posthumous popularity is a review of a musical homage to Barbara that appeared on the website of the French daily Le Monde on December 16, 2003. The journalist mentioned the two most disturbing episodes in the singer’s life: having to be hidden as a child during the occupation; and having suffered sexual abuse in the same period, at age ten, at the hands of her father. He is buried in a common grave in a cemetery at Nantes; his death is alluded to in Barbara’s song whose title is simply the name of that city.

Jewish Identity

Like the Jewish origins of Serge Gainsbourg (b. Lucien Ginsburg, Paris 1928, d. Paris 1991) and Georges Moustaki (b. Yussef or Giuseppi Mustacchi on May 3, 1934, to a Greek-Jewish family in Alexandria, Egypt), Barbara’s ethno-religious background is primarily of anecdotal interest, somewhat like the fact that Israel was a concert destination for her. Her Jewish identity, well-known to her adoring public, is certainly part of her non-conformist persona. Her wartime experience as a child refugee constitutes an element of pathos in the mythology surrounding her as a suffering artist. In her memoirs she writes:

It was difficult to pass unnoticed when we arrived in a new location. Our parents told us to say nothing of our lives.

Say nothing! With our different looks, and the arrogance with which I said, precisely, that I was Jewish.

“So what of it?”

So what of it? I wasn’t ashamed or particularly proud of being Jewish, but seeing how others looked at me differently made me aggressive. (Il était un petit piano noir, 35–36)

Barbara’s Jewishness certainly contributed to her becoming something of a poster child for Franco-German reconciliation. In an episode well-known to her fans, she portrays her song “Göttingen” as the end of a process that started with her distaste at the idea of singing in Germany: “Pas question d’aller chanter en Allemagne” (Il était un piano noir, p. 162). The story goes that her German hosts were surprisingly helpful in arranging for a proper piano to be brought. She penned these words of gratitude:

When the blond children of Göttingen

Don’t know what to say

They stand there and smile

But we understand them all the same

And too bad about those who are astonished

And may the others pardon me

But children are the same

In Paris or Göttingen

Oh, may the time of blood and hatred

Never return

For there are people I love

In Göttingen, in Göttingen

But if the alarm should sound

And arms be taken up again

My heart will shed a tear

For Göttingen, for Göttingen

A careful reading of the song suggests wariness: there is the possibility that arms might once more be taken up against Germany. Barbara herself wrote of a “profound desire for reconciliation, but not of forgetfulness” (Il était un piano noir, p. 168). But the popular memory of the lyrics is more positive regarding the neighbor across the Rhine. After all, Barbara composed the song in 1964, when the Federal Republic was just beginning to re-enter the concert of nations; only one year before that, de Gaulle and Adenauer had signed the Élysée Treaty on Franco-German cooperation.

Legacy

On November 22, 2002, five years after the singer’s death, the city of Göttingen named a Barbarastrasse in her memory. The following January, when celebrations were being held at the highly symbolic Versailles palace to honor the fortieth anniversary of the historic accord between de Gaulle and Adenauer, Barbara’s name came up again. Gerhard Schroeder— the German chancellor whose opposition to a U.S. campaign in Iraq would soon lead him to forge a particularly close alliance with French president Jacques Chirac—waxed nostalgic about Barbara:

She came to sing it [the song “Göttingen”] in Germany in 1967. … There were those words: “Children are the same in Paris and Göttingen. Oh, may the time of blood and hatred never return, for there are people I love in Göttingen, in Göttingen.”

Unfortunately, I never had the chance to see Barbara, but she touched our hearts. (Le Monde, January 24, 2003)

Barbara (Serf, Monique). Il était un piano noir: Mémoires interrompus. Paris: Fayard, 1998.

Davet, Stéphane. “Spectacle: L’hommage sans fétichisme de Serge Hureau à Barbara.” Le Monde, December 16, 2003.

De Chenay, Christophe. “Une cérémonie en présence de MM. Chirac et Delanoë.” Le Monde, September 4, 2003.

Faurant, François. francois.faurant.free.fr/biographie/barbara_biographie.htm (January 3, 2004). “Le jour où la France et l’Allemagne ont célébré leur réconciliation.” Le Monde, January 24, 2003.

“Monique Serf.” Simon, Catherine. “Aux obsèques de Barbara: ‘Dis, quand reviendras-tu?’” Le Monde, November 29, 1997.