Bronia Klibanski

From a young age, Bronia (Bronka) Klibanski had practice defying authority. When the Nazis invaded her hometown in Grodno, Poland, she discovered a knack for tricking guards and for sneaking in and out of the ghetto walls to bring food back to friends and family. Her sense of adventure and quick wit, not to mention her good looks and self-confidence, made her well equipped to join the resistance of the Kashariyot organized by Mordechai Tenenbaum. She survived the war and saved numerous Jewish lives, while also arming Bialystok resistance fighters and saving the contents of the ghetto archive. She moved to Jerusalem in 1953 and worked at Yad Vashem as an archivist until her retirement.

Bronia (Bronka) Klibanski is well known as one of the heroic CourierKashariyot of the Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. She worked with Mordechai Tenenbaum, the leader of the Jewish resistance in the Bialystok ghetto, becoming the primary kasharit for the Dror Zionist group in 1943. She obtained critical weapons for the ghetto revolt, gathered intelligence, rescued other Jews, and saved the secret archive of the Bialystok ghetto. She continued her underground activities after the Bialystok ghetto was destroyed, working with a group of five young women from other movements to continue rescuing and helping Jews. They also smuggled weapons, supplies and medicine to the partisans in the forests near Bialystok and were awarded medals as heroines of the USSR after the war.

Early Life

Bronka Klibanski was born on January 24, 1923, to Bashia and Leib Vinitski in Grodno, Poland. She had two younger sisters, Dvora and Shulamit, and a much younger brother, Shalom. Her mother, an actress and singer in the Jewish theater before she married, inspired her children’s love of Yiddish music, culture, and literature with her yearning tales of Palestine and beautiful Jewish songs. When Bronka’s father, a cattle dealer, lost most of his customers in the depression of the early 1930s, her mother became the family provider by opening a kiosk to sell fruit and sweets.

It was an attack on the kiosk that led Bronka first to Zionism and later to her underground activities during the war. In 1935, just when her mother’s newly built wooden kiosk was making enough income for Bronka to have violin lessons, it was trashed and destroyed by an antisemitic mob in a government-supported pogrom. Twelve-year-old Bronka decided that she did not want to live in a country where Jews were hated: she would go to Palestine. She joined the Dror Zionist youth group to prepare for Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.aliyah.

Bronka was still in school on June 22, 1941, when the Germans invaded Grodno. Her family’s home was hit by a bomb and consumed in flames, leaving Bronka’s parents, their four children, and her grandmother with no place to sleep and no resources to help them withstand the assaults of the German invasion.

“From the beginning I was not following their orders”

One of Bronka’s earliest acts of defiance occurred during this period. Bronka was put in charge of a group of Jewish girls conscripted for forced labor for the Germans. When it began to rain, Bronka told their German overseer that they “did not work outside in the rain.” Since she had not asked, but had simply stated the policy with authority, the German acquiesced.

While this experience emboldened Bronka, she was in fact bold, self-confident and sure of what was “right” from the start. She acted as if she expected the Germans to accept this, and, surprisingly, many of those she encountered did. She had an intuitive sense of how to accomplish whatever she set out to do, whether through her elegant poise, her simple politeness, or her sparkling blue eyes.

The 30,000 Jews in Grodno were ordered to move into the ghettos in a single day on November 1, 1941. When Bronka saw the long lines and the way the German guards were inspecting and harassing the Jews, she decided to find another way to get into the ghetto. Once again she succeeded, and once again she was empowered. As she said: “From the beginning I was not following their orders.”

Bronka’s talent for slipping in and out of the ghetto soon led her to smuggling to get critically needed food for her family, to “bring home something to ease the gnawing hunger” (1998: 175), because the Germans intentionally set the ghetto rations at starvation level. She would sneak out of the ghetto with some clothes or linens to trade for food, and would smuggle the food back into the ghetto. Soon other people in the ghetto, who were afraid to take the risk themselves because Jews caught outside the ghetto risked death, offered her a commission for trading their goods as well.

Bronka had several characteristics that proved to be critical assets for her smuggling, as well as for her later success as a kasharit for the Jewish resistance. First, she had what she called “a good face,” did not look Jewish and would not be easily identified as a Jew on the Aryan side. Second, she spoke colloquial Polish with no trace of a Jewish accent. Third, she had lived among non-Jewish families and had former neighbors she could trust to be steady “customers.” Finally, she was adventurous and fearless: while others were terrified of the danger of being caught as a Jew outside the ghetto, Bronka made a sport of finding new ways to get in and out. At eighteen, she was young enough to assume that “nothing could happen to me.”

Joining Dror

The dramatic event that changed Bronka’s life was a meeting with Mordechai Tenenbaum, one of the national leaders of her Zionist youth group, Dror, when he came to the Grodno ghetto in January 1942. It was Tenenbaum’s shocking news of the mass killings of the Jews of Vilna in the forests of Ponary and his analysis of the systematic murderous agenda of the Germans that led Bronka to active resistance.

One month later, in February 1942, Bela Hazan, a Dror kasharit, came to the Grodno ghetto to tell Bronka she was summoned to Bialystok for a national meeting of Dror leaders. Since it was too risky for them to travel together, Bronka had to get to Bialystok by herself. It seemed like an impossible assignment: Jews were not allowed to travel—they were not even allowed outside the ghetto—and Bronka did not have the documents or the money to buy a ticket.

Once again, her talent for “on the spot improvisation” stood her in good stead. At the train station, she saw a German officer. She approached him “and asked him, very nicely, if he could buy me a ticket. And he said, yes, why not.” While Bronka describes herself as very polite, she does not mention that she was also very beautiful, with strawberry blond hair, sparkling blue eyes and a warm smile that made others want to help her.

Bronka also had the advantage of inheriting her mother’s talent as an actress and found it easy to play whatever part was required. For example, when she faced the next set of obstacles getting into the Bialystok ghetto, she started running toward the gate and breathlessly told the guard that she had to go back to get the sewing she had done for her German boss. Again, she got through.

Bronka returned to Grodno after the Bialystok meeting, but she was pledged to secrecy and could not tell her parents about her underground activities. Nor could she tell her mother she was leaving Grodno when she was called back to Bialystok two months later, but she felt the hurt and sadness in her mother’s eyes as she sensed that Bronka was leaving forever. That last image of her mother was seared in Bronka’s memory.

The April 1942 meeting of the Dror members from surrounding ghettos—who had risked their lives to come to Bialystok for the “A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Pesah seminar”—was led by Frumka Plotniczki, a national leader of Dror, who had come from Warsaw. It was an exciting event, lightyears away from the grim reality of the ghettos they had left, and the members were inspired and energized to mobilize resistance. When Bronka was asked to stay in Bialystok, she was willing and eager.

They all lived in a communal house they called A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Tel Hai. Bronka was given a job in the ghetto’s vegetable garden in the summer of 1942 and in the fall “sewed buttons that looked O.K. but were likely to fall off” in a factory that made German military clothing. At night, when they returned from their jobs, they would gather at the long table to talk, argue, and plan. Bronka, responsible for their cultural activities, might entertain them with stories from Shalom Alechem, Yiddish folk songs and arias she learned from her mother.

Becoming a Kasharit

In November 1942 Tenenbaum returned from Warsaw to organize the resistance in Bialystok and soon tapped Bronka to become a kasharit (courier) for the Dror movement. By the end of 1942, all but one of the Dror kashariyot had been caught by the Germans, and Bronka’s skills were keenly needed. Tenenbaum needed someone with the courage to undertake the dangerous task of securing weapons for the ghetto revolt, but he also wanted someone who looked innocent and would remain calm and self-assured in a crisis. Bronka was the ideal candidate, not just because of her “Aryan” appearance, calm manner, colloquial Polish and personal comfort in the non-Jewish world; most important, as she herself noted, was her courage and confidence: “I was not afraid … and I would not get caught.”

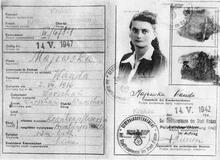

Armed with little more than her German-issued identity card, Bronka left the ghetto on the last day of 1942. For the next eight months she was totally alone—and on her own—on the Aryan side. She was surrounded by people who hated Jews and who would have been happy to turn her in to the Gestapo. That was not just a hypothetical concern. Although Tema Sznajdermann, the only surviving Dror kasharit in Bialystok, had found a room and a job for Bronka (before Tema left for Warsaw), her neighbors suspected that she might be Jewish because it was unusual for a young girl to live alone, and even more unusual for her to have no one from her family come to visit her. The neighbors’ concerns led them to scrutinize her activities in order to unmask her if she was really a Jew. They were especially vigilant about scrutinizing everyone who came to her door. One day five Jewish girls who had escaped from Grodno appeared at Bronka’s flat. She had no idea how they found her, but she agreed to hide them when she went to work. However, the neighbors had already seen them, and they immediately told her landlady that “Bronka was hiding Jews.” That night Bronka faced down a Gestapo officer with one of the amazing performances of her career and managed to persuade him to leave. The next day she moved the girls.

Bronka’s real purpose on the Aryan side was her missions as a kasharit. Her first and most important assignment as a kasharit was to buy arms for the resistance and to deliver them to the ghetto. Her second crucial mission was to find a secure place outside the ghetto where the underground archives of the Bialystok ghetto could be hidden and saved. She was also responsible for collecting information and intelligence for the ghetto underground, rescuing other Jews and serving as a one-person communication center for mail and information that linked the ghetto to the world outside. As the only Dror kasharit on the Aryan side of Bialystok (after January 1943), she bore the enormous weight of conducting these missions alone.

When she was outside the ghetto she lived an ever-vigilant, disciplined and lonely life. She could not relax until she was back in the ghetto, and she looked forward to and lived for those times. As her relationship with Mordechai Tenenbaum developed from friendship to love, her frequent visits to the ghetto and the letters they exchanged sustained her and gave her “enormous strength and self-confidence … in the shadow of the inevitable end” (1998, 180–181).

Arming the Bialystok Uprising, Preserving the Archive

The single biggest problem that Mordechai Tenenbaum faced was the lack of weapons for the would-be fighters in the ghetto. (In August 1942, when they were starting to talk about resistance, the underground had only one gun.) That was what they most needed from Bronka, and that was the arena in which her talents were most evident. For example, on her first mission for weapons she traveled to a rural village to get a revolver and two hand grenades. The farmer “packed” the weapons in a huge loaf of country bread and she walked back to the train station happily anticipating the joy that would greet her delivery. But a German policeman with a large dog was standing on the platform at the station. He looked at her suitcase suspiciously and asked what she was carrying. Realizing that she could not avoid his inspection, she decided to adopt a friendly posture and, with a smile, confessed that she was carrying food from the farmers, thereby admitting that she was smuggling. Surprisingly, the German became her protector. He instructed the conductor to keep an eye on her and to be sure no one disturbed her suitcase (2002, 58).

Bronka’s efforts to accomplish her second mission and to find a hiding place for the ghetto archives were less dramatic but equally fraught with danger. The archive was the ghetto’s legacy, the diaries, testimonies, reports—even the records of the Judenrat—that Zvi Mersik and Mordechai Tenenbaum had collected to document the experiences of the Jews in Bialystok and the cruelty of the Germans. Each time Bronka set out to investigate a potential hiding place she encountered such strict searches on the trains that she decided she could not to risk transporting the archives. In the end a Polish friend, Dr. Filipowski, agreed to hide the materials on his land, and Bronka smuggled them out of the ghetto. (The archives survived the war and are now in Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.) When the uprising in the Bialystok ghetto began on August 16, 1943, it became impossible for anyone on the Aryan side to reach the fighters. This was a time of great anguish for Bronka—watching three rings of armed German soldiers and SS men surround the ghetto, seeing them enter, hearing the barrage of gunshots, knowing that Tenenbaum and all her friends were in the ghetto, and being unable to do anything whatsoever to help them. Despite the danger, Bronka was drawn to the ghetto and kept walking around the walls, hoping that she might find some way to communicate with and help her friends.

On the first day of the uprising, by chance Bronka met Haika Grosman, one of the leaders of the unified Jewish resistance in the ghetto and a kasharit for Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, and Marylka Rozycka, the kasharit for the Jewish partisans in the forests near Bialystok. Realizing that they might be the only survivors of their movements, they pledged to work together to save any Jews who managed to escape and to help them reach the Jewish partisans in the forests. In addition, they pledged to help the Jewish partisans who were themselves in dire need of supplies. The three of them were soon joined by the surviving kashariyot-members of other groups: Liza Czapnik and Anya Rod from the Communists, and Hasia Bornstein-Bielicka and Rivka Madajska from Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir.

Joining Forces with the Red Army

After the Bialystok ghetto was liquidated, and Tenenbaum and most of the fighters were killed or committed suicide, this newly formed group of young women kashariyot from different groups began to work together to rescue Jews from other ghettos, labor camps, prisons, and deportation trains and to help them reach the group of Jewish partisans in the forest. As a result, the Jewish partisan group, the Forojs (Forward), grew from 50 to 100 people. Bronka tried to save some of the survivors of the uprising, but only one was willing to accept her help. She also rescued one man who escaped from Treblinka and helped him reach the partisan group.

In the spring of 1944, the Soviet paratroopers reached the forests and began to unify the groups operating there. The Forojs joined the Soviets and their material situation improved greatly. Bronka’s group of young women also joined the Soviets and became couriers for the Soviet headquarters of the partisan groups, which was coordinated with the Red Army.

In May 1944 the Soviets established an official anti-Fascist Committee in Bialystok and named Liza Czapnik as its leader. Liza and the other women in the group, who continued to work together as equals, provided critical assistance to the Russian partisan command in the forests and were able to supply them with sorely needed weapons, food, medicine, blankets, and clothing. (Bronka provided the medicines which she got from Dr. Filipowski, an employee of a German pharmaceutical warehouse.) The young women also gathered intelligence for the Russians and provided them with detailed information about the Bialystok airport and German military installations. In the last few weeks of the war Bronka unexpectedly participated in blowing up a German train that was rushing troop reinforcements to the front.

Bronka met her future husband, Michael “Misha” Klibanski, in Bialystok in the summer of 1944, after liberation. He had been in the Polish army, escaped to the Soviet Union at the beginning of the war and was sent back as a Russian parachutist to help the partisans in the winter of 1943.

After the War

After the war Bronka became a counselor for teenage survivors in the first kibbutz, a group home in Warsaw for children who lost their entire families in the Holocaust.

Misha had injured his hip on a jump during the war and suffered from severe pain. He spent the first years after the war receiving medical help and recovering in Switzerland. Bronka resumed her studies in Geneva, receiving her basic degree in 1950, and from 1950 to 1953 they both studied in Zurich, where Misha completed his Ph.D. in economics in three years. Bronka, who wanted to be an actress, studied art and theater.

The couple came to Israel in 1953 and settled in Jerusalem. Their son Eli was born in 1957. Since the Habimah Theater was not welcoming to new immigrants, especially those who did not speak Hebrew, Bronka began to work as an archivist at Yad Vashem in 1955 and held that position until she retired. She was instrumental in preserving and publishing the diary and letters of Mordechai Tenenbaum and the underground archive of the Bialystok ghetto, creating the Mersik-Tenenbaum Archive. She also compiled the collected documents from many countries, including Germany, Yugoslavia, Hungary, France, Belgium, and Slovakia, and the list of testimonies in the 033 central archive. Her facility with languages and her personal warmth were of enormous help to several generations of scholars. In 2002, her beautifully written account of some of her wartime activities, Ariadne, was published in Israel.

Bronka Klibanski died on February 23, 2011.

Selected Works

“The Underground Archives in the Bialystok Ghetto, founded by (Zvi) Mersik and (Mordechai) Tenenbaum.” Yad Vashem Studies 2 (1958): 295–332.

“The Bialystok Revolt.” Yalkut Moreshet 36 (Hebrew) (1983) 32–39.

“Five Hundred Years of Jewish Settlement in Podlasie.” Paper presented at an international conference, Bialystok, 1987. Published in Studia Podlaskie 2 (in Polish) (1989).

“Children in the Theresienstadt Camp.” Yalkut Moreshet 54 (Hebrew) (1993): 125–132.

“L’affaire du transfert de 1200 enfants du ghetto de Bialystok au camp de Theresienstadt.” (The case of the transfer of 1200 children from the Bialystok ghetto to Theresienstadt concentration camp). Le Monde Juif 155 (1995): 143–155.

“In the Ghetto and in the Resistance: A Personal Narrative.” In Women in the Holocaust, edited by Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, 179–186. New Haven: Yale University Press. 1998.

Ariadne (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Geranium Publishers, 2002.

Archival Collections Compiled by Bronka Klibanski

Collection of documents on the destruction of German Jewry. Yad Vashem: 1975.

Collection of documents on the destruction of Yugoslavian Jewry. Yad Vashem: 1976.

The Archives of the Swiss Consul General Charles Lutz. “Labor Batallion in Slovakia, Cumulative Index of Vols. 1-XV.” Yad Vashem Studies 15 (1983): 357–366.

Collection of documents on the destruction of Hungarian Jewry. Yad Vashem: 1984.

Personal interviews with Bronka Klibanski in Jerusalem by Lenore J. Weitzman on June 12, 1993, June 21, 1994, December 19, 2003, and January 21, 2005.

Tenenbaum, Mordechai. Pages from the Fire: Chapters of a Diary, Letters and Essays, edited by Bronka Klibanski and Tsevi Shner (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1984.