Tema Sznajderman

Born as World War I came to a close, Tema Sznajderman grew up in Poland during the interwar period. In 1942, Sznajderman traveled to Bialystok to become a courier for the He-Halutz-Dror throughout the German-controlled areas. Sznajderman worked to aid Jews to hide their identities and assume Christian ones. Together with Mordechai Tenenbaum, her fiancé, she forged many documents that aided their Jewish comrades in fleeing to Turkey and Palestine. Sznajderman also undertook the dangerous mission of traveling to ghettos to report on their conditions and encourage resistance to the Germans. She was last heard from on January 13, 1943, after crossing the border into Poland, headed for Warsaw; she was killed 5 days later in an aktion and the first uprising in the Warsaw ghetto.

Introduction

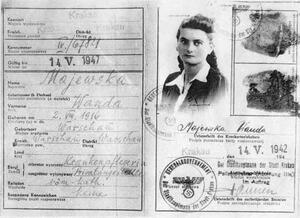

The real heroes of the Holocaust period are mostly those who did not survive, remained little known, and had no myths built around them. One such person was Tema Sznajderman, also known by her Aryan name of Wanda Majewska, one of the first couriers and an especially brave one.

In December 1942 Tema Sznajderman arrived in Bialystok from Warsaw, following Mordechai Tenenbaum (1916–1943), who had been sent by the Jewish Fighting Organization (ZOB) to organize the underground and the Bialystok Ghetto rebellion. At that time, Sznajderman remained almost the only courier who worked for He-Halutz-Dror throughout the German-controlled areas. Two other couriers, Lonka Koziebrodzka and Bella Hazan, were arrested in June 1942 as they crossed the border at Malkinia and vanished without a trace. They were suspected of belonging to the Polish underground and taken to the Paviak Prison in Warsaw where, despite prolonged interrogation, they did not reveal their Jewish origins. Much later it was learned that in December 1942 they were sent to Auschwitz with a transport of Polish political prisoners.

In March 1942, the Bialystok district was annexed to eastern Prussia, and the Christian population was ordered to carry Personalausweis, German identity cards. With Sznajderman’s approval, Mordechai asked Bronia Klibanski-Winicki to serve as a courier on the Aryan side. She was given a forged Christian birth certificate and sent as a proper Polish girl to obtain a German identity card. Later, Sznajderman came to her aid, finding her a room in the city and a suitable job with three Zugführer, German train conductors. This was significant help for a young, inexperienced woman who went out of the ghetto walls into the wide, unfriendly world—help which considerably endangered Sznajderman. Tema Sznajderman was Bronia’s alibi, the cover for her Polish identity and the proof that she was not Jewish. She was an example of determination and daring for Bronia to emulate in her new life.

Childhood

Tema Sznajderman was born in Warsaw in 1917 to a family that was neither religious nor assimilated. They spoke Polish at home. She had a sister, Rachel, and a brother, Shlomo. Her mother died when she was twelve and from childhood Sznajderman learned to be independent and care for her family and other people. Within a year her father remarried and in time two other children, Bella and Yaffah, were born.

After graduating from Polish public school Sznajderman studied nursing and began to work in a hospital. She met Mordechai Tenenbaum through a mutual friend and under his influence joined the He-Halutz-Dror youth movement and learned Yiddish. Tenenbaum brought her into the movement and also into the world of his life and dreams, and also paid close attention to her advancement and her studies. The Tenenbaum household welcomed her, and she visited it together with her six-year-old sister Yaffah, whom she cared for lovingly.

Tema Sznajderman was tall and beautiful. Her face, crowned by two auburn braids, radiated gentleness, her mouth expressed determination and her eyes contained a deep sorrow, as though she knew what was to come. She wore elegant, casual clothing and in winter sported black boots according to the latest fashion. She smiled a great deal but was emotionally controlled and more practical than Tenenbaum. She was enchanted by his high intellectual level and the two became close, each complementing the other in a kind of rare spiritual exaltation.

Signs of Trouble

According to the June 4, 1936 edition of the Jewish newspaper Haynt, published on the first day of the pogrom in Minsk Mazovyetsk, “An unknown man, Mordechai Tenenbaum of Warsaw, was arrested together with his fiancée, Tema Sznajderman and her sister Rahel, also of Warsaw. It appears they will be released, since there are no charges against them.” Evidently their visit to Minsk Mazovyetsk was not coincidental. They went there to see for themselves what was happening there and perhaps to encourage the Jews of the city not to flee but to stay and fight. Sznajderman knew the place well since she had visited her stepmother’s family there many times, and she could tell the police she was once again visiting family.

At the beginning of 1938 Tenenbaum’s father died. When the months of mourning were over he left home to join the commune of the He-Halutz youth movement. He was active mostly in education and culture and took part in the movement’s ideological newspaper Unzere Yedios, winning a great deal of recognition from his comrades. Sznajderman, too, loved and admired his colorful personality.

At the same time, Sznajderman’s family suffered several tragedies in succession. First her father died and when World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, her home took a direct hit in a German bombing, which killed her mother and her sister Bella. Her six-year-old sister Yaffah moved to Minsk Mazovyetsk at the family’s demand and was the only one to survive the war and the Holocaust, thanks to help from Poles.

Race to Flee Poland

Sznajderman joined Mordechai and together with the members of the Dror A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz left Warsaw and made contact with the areas under Soviet control, first Kovel and then Vilna. Many refugees of all sorts also joined, including all the shelihim (emissaries) from Palestine and those who had certificates or entry visas to countries abroad. Members of the training farms (kibbutz hakhsharot), who for years had waited to immigrate to Palestine, unfortunately did not receive any certificates. Everyone sensed the danger and sought ways to flee Europe.

Mordechai Tenenbaum used all his resourcefulness and, together with Sznajderman, tried to help those who did not possess the required papers. First, they organized the emigration of the emissaries from Palestine and those who had certificates, obtaining assistance from the Joint Distribution Committee to cover travel expenses. They also began to forge documents that would allow the emigration of as many comrades as possible. The arrangements for the emigration of groups of members were based on a letter from the British government confirming that the certificates for the group awaited them in Turkey. Sznajderman, who had considerable artistic ability, forged such letters and the appropriate signatures. In this way Tenenbaum’s younger sister Tamar was able to reach Palestine in the last group, together with ninety comrades. Sznajderman insisted that Mordechai include Tamar in one of the groups after he had excluded her in favor of others whom he believed to be more deserving. The group traveled from Vilna by way of Moscow and Odessa to Turkey, arriving in Palestine two months later.

Dangerous Trips to the Ghettos

After the Germans overran Vilna in the summer of 1941 and established the ghetto, Sznajderman remained outside, visiting other ghettos in Lithuania and being the first to bring documented proof of the mass slaughter of Jews in Ponary (an extermination site 10 km. from Vilna). Arriving in Bialystok, which at that time had not yet suffered any aktions, she met with members of the movement and also with the head of the Judenrat, who agreed to let her bring the surviving members from Vilna. She returned to Vilna and with the help of an Austrian Wehrmacht sergeant, Anton Schmid, accompanied a group of twenty members to the Bialystok ghetto in an extraordinarily daring operation. From there she traveled once more to Warsaw, visiting the Czestochowa, Cracow and Bendin ghettos, bringing news of the movement, encouragement, money and information about the situation of the Jews to every member. On her return to Warsaw she gave detailed reports about what was going on in every place she had visited, which were published in underground newspapers and the report deposited in the Emanuel Ringelblum (1900–1944) clandestine archives.

Sznajderman also accompanied comrades, among them Frumka Plotnicka, a member of the movement’s central committee, when she visited Bialystok, Volhynia and the Ukraine region. Though travel to these places was difficult, they still managed to reach many ghettos there and encourage the Jews, find friends, call on people not to believe the Germans and their false promises, and encourage resistance.

These trips, which were extremely dangerous, demanded extraordinary courage and ability to improvise. They were vital for breaking the isolation that the Germans enforced on the ghettos, together with a strict prohibition of any contact between them. Sznajderman embodied the spirit of protest and disobedience to the occupier’s orders and prohibitions, the spirit of freedom and rebellion that beat within her heart and influenced the members to dare, not to be afraid and to cope.

Marriage to Mordechai

Later, during the destruction, Sznajderman worked closely with Mordechai Tenenbaum. He loved her very much and would send her on the most dangerous missions. Unlike the mother’s love in Itzik Manger’s poem “Oyfn Veg Shteyt a Boim” (A Tree Stands on the Road), which prevented the poet from being “like a bird in flight,” their love spread wings and inspired spiritual exaltation and courage.

Tenenbaum decided to take her name out of love, and his forged documents bore the Tatar-Karaite name Tamaroff, incorporating her Hebrew name, Tamar. With the help of this document and despite his pronounced Jewish appearance, he visited dozens of ghettos such as Grodno, Bialystok, Warsaw, Cracow, Czestochowa and Bendin.

Both he and Sznajderman were in Warsaw during the great aktion that began there on July 22, 1942, and organized forged work papers to try to save others. In November 1942 Tenenbaum was sent to the Bialystok ghetto. Sznajderman followed him, bringing the gaiety and fragrance of the outside world. As generous as Tenenbaum, she never forgot to bring some sort of gift for her friends in the ghetto such as wild flowers she had picked or smuggled lemons, or an article of her own clothing that a friend of hers needed.

An essay of hers survives, signed with the initials of her Aryan alias, Wanda Majewska. Entitled Szlakiem Bestialstwa Hitlerowskiego (In the Path of Hitlerite Bestiality), it was meant as propaganda for German soldiers and contains an account of atrocities and murder committed against Poles and Jews. It was translated into German and published by the Polish underground in an illegal newspaper.

Dangerous Clandestine Work

On January 11, 1943, at Tenenbaum’s behest, Sznajderman traveled again to Warsaw to bring the Jewish Fighting Organization money and instructions for manufacturing grenades and Molotov cocktails. She was also to pass German documents (copies of circulars from German government ministers Albert Speer and Heinrich Himmler about annihilating the Jews even at the price of weakening the war effort) to London through members of the Armia Krajowa (AK, the Polish underground). On January 13, a telegram was received from Sznajderman, reporting that she had crossed the border successfully into the Generalgouvernement. This was the last trace of her. It is now known that after she passed the German documents to members of the AK in Warsaw, she entered the ghetto, and on January 18 was killed during an aktion and the first uprising there. Mordechai dispatched many telegrams and letters to all addresses of her friends outside the ghetto, but no response was ever received. Not even her closest friends in the Jewish Fighting Organization ever troubled to notify anyone of what had happened. Mordechai interpreted this to mean that everyone had fallen. Contact with Warsaw was interrupted and never resumed. Only in March did notification of Sznajderman’s death on January 18 in the Warsaw Ghetto arrive.

Sacrifice

Inconsolable, Tenenbaum felt isolated from the world and from his friends in the Jewish Fighting Organization, who never tried to renew the connection with him. He improvised a kind of shrine to Sznajderman’s memory in his room, surrounding her picture with flowers. Many of his writings lamenting her death survived in the archives of the underground—a fitting memorial, he said, to her love and heroism, devotion and sacrifice. “She was a living encyclopedia of the tormented life of Polish Jewry,” he wrote. “With her death, we all have died. Our lives were bound up with hers. More than once we pleaded: In any case, all will be lost. Let go of this, live, live at any cost, tell the stories, since you know so much. She would laugh as she always did. And now she is gone. Not even a trace of us will remain.”

Sznajderman had a special place in the history of the Dror youth movement and in the life of Mordechai Tenenbaum. Her logical thinking skills were impressive, as were her understanding of others and her self-restraint. These qualities frequently helped Tenenbaum to carry out important tasks in each of the three ghettos—Vilna, Warsaw and Bialystok.

Schoeps, Karl-Heinz. "Holocaust and Resistance in Vilnius: Rescuers in "Wehrmacht" Uniforms." German Studies Review 31, no. 3 (2008): 489-512.