Photographers in the United States

There is no simple way to categorize Jewish American women photographers, who are a highly diverse group. Links, however, exist among some of them. A significant number of Jewish American women photographers have had a strong social conscience—whether they were born to wealth as were Doris Ulmann and Diane Arbus, or in working-class neighborhoods, as were Helen Levitt and Rebecca Lepkoff, or come from abroad, as did Sandra Weiner. Many seem to reject pretty subjects and conventional techniques, in favor of work that is intellectually probing, wryly amusing, radical, or even disturbing. Many appear to want their work to serve some moral, historical, or humane purpose, however subtly expressed. Finally, many went to art school and only later, often by accident, found their way to photography.

Introduction

There is no simple way to categorize Jewish American women photographers—they are too diverse a group. They come from distinctly different political periods, economic strata, and even cultures (some were born abroad). They share neither mind-set nor style, their subjects and interests vary widely, and their worldview and art seem to have little to do with their Jewish identity.Links, however, may exist among some of them. Allowing that this characteristic may be common to the artistic temperament in general and to women artists in particular, a significant number of Jewish American women photographers seem to have a strong social conscience—whether they were born to wealth as were Doris Ulmann and Diane Arbus, or in working-class neighborhoods, as were Helen Levitt and Rebecca Lepkoff, or come from abroad, as did Sandra Weiner. Many seem to reject obviously pretty or pleasing subjects, and sometimes conventional techniques, in favor of work that is intellectually probing, wryly amusing, radical, provocative, or even profoundly disturbing. And many appear to want their work to serve some moral, historical, or humane purpose however subtly expressed. Even Annie Leibovitz, the ultimate “celebrity photographer,” documented the tragedy of Sarajevo, where she traveled with noted photography critic Susan Sontag. Finally, many went to art school to study sculpture or painting and only later, often by accident, found their way to photography. Many seemed to feel it was a much less demanding medium to master than other art forms.

From the time of its invention in 1839, and for some period thereafter, photography was regarded more as a scientific invention and curiosity than a new and valued fine art—the talents of women, therefore, were deemed appropriate for it. What is more, women found in photography fewer obstacles to their progress than in the traditional fine arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. Photography, then, offered women a career, a way to earn a living, and a medium for artistic expression.

Portraiture

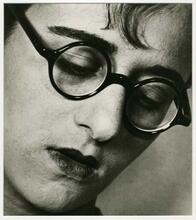

Portraiture was a natural subject for photographers. With the advent of photography, portraits suddenly became a reality not only for the middle classes but even for the masses. It was a genre many women found congenial, including many Jewish American women photographers, and some specialized in it—at least for periods within their careers.

It must be understood, however, that “portraits” come in many guises and depend on many factors: the motive of the photographer, the complicity (or lack of it) of the sitter, and the variables of lighting, focus, and composition.

Doris Ulmann (1882–1934) was born to wealth and raised on New York City’s Park Avenue. Like other women of means, she took up photography as a hobby and as a creative outlet. A student of sociologist/photographer Louis Hine (who used photography to make people aware of the plight of recent immigrants) and later of photographer Clarence White, Ulmann established her reputation by publishing portfolios of the medical faculties of Columbia and Johns Hopkins universities. Because she worked to please herself, she rarely photographed anyone in whom she was not interested. Her subjects in the early 1920s were prominent urban artists and intellectuals (Albert Einstein, Thornton Wilder, Paul Robeson, for example), who posed at Ulmann’s request and expense.

Later in the decade, her work took a new direction as she set out to document rural life. Traveling to New England, New York, and Pennsylvania, she photographed Mennonites and various Shaker settlements. Later, in the rural South, she recorded South Carolina’s Gullah people, Creoles, and Appalachian mountaineers. Why the interest in cultural anthropology? The early death of Ulmann’s mother and the photographer’s own delicate health as a youngster, as well as exposure to Hine, no doubt sensitized her to the dignity of human struggle. Also, she wanted to record a disappearing way of life and to serve some social purpose. However, this body of work could never be mistaken for an objective record; although handsome, the images romanticize and idealize their subjects.

Trude Fleischmann, who took up photography at age nine, grew up in a prosperous Jewish family in Vienna. On returning there after studying art history in Paris, she opened a thriving portrait studio in 1918, drawing her subjects mainly from the world of actors (Hedy Lamarr [link to new entry on Hedy Lamarr], Katharine Cornell), dancers, and musicians (Bruno Walter). While her early work was brown-tinted and soft-focused, she favored a more “modern” sharp-focused approach. Later in New York, Lotte Jacobi (1896–1990), born in Germany, likewise specialized in portraits of artistic and scientific achievers (Einstein, Thomas Mann, J.D. Salinger).

Rebecca Lepkoff’s (b. 1916) work evolved in ways similar to Doris Ulmann’s. Born on New York City’s Lower East Side, she concentrated on the city’s streets in her early work, producing portraits and city views. After moving to Vermont, she photographed the local people (farmers, homemakers) in their world.

During her career, Ruth Orkin did portraits, photojournalism, and street photography, and also codirected films (The Little Fugitive, Lovers and Lollipops). In the 1950s, she photographed illustrious actors and musicians (Marlon Brando, Woody Allen, Leonard Bernstein, Isaac Stern). One of her more interesting later projects was to take pictures throughout the year from the window of her Central Park West apartment. Given the limitations of her perch, the variety of images is impressive—she documented shifts in light, clouds, weather, and a parade or two.

Judy Dater (b. 1941) uses portraiture toward a totally different end from her older colleagues, and there is an unmistakable feminist slant to her work. Using herself and others costumed or nude as models, she explores women's roles, strengths, and vulnerabilities. At its best, her work displays a caustic humor in the images and titles: “Elephant Woman Steps Out” or “Death by Ironing.” In her earlier work, content is clearly at the center (women’s identities, stereotypes, and sexual roles); aesthetics was not a major consideration. More recently, she has experimented with constructions consisting of portraits and various evocative scenes arranged in differently configured grids. She has also been experimenting with computer-altered images.

Annie Leibovitz, whose own celebrity rivals that of many of her sitters, is one of today’s highest-paid and most sought-after commercial photographers. Her specialty is portraits of celebrities, and, as critic Charles Harding observes, “a startling number of her images have become icons of popular culture.” Some critics have dismissed her work on the arbitrary grounds that it is commercial, deals with popular culture, and rarely seems to get “below the surface.”

Her portraits are unidealized and striking for their sharp wit, for her inventive use of props, and for her habit of parodying what she sees as her subject’s persona. She photographed Whoopi Goldberg submerged in a milk bath, roaring with laughter; Demi Moore nude and very pregnant for a cover of Vanity Fair; Roseanne and Tom Arnold wrestling in the mud (Vanity Fair). Her portrait of artist Keith Haring is particularly apt. Nude, he becomes a piece with the room he poses in—his body, the walls, couch, lamp, and even the coffee table on which he stands are all white and painted with his trademark black “primitive” writing.

Leibovitz’s childhood was unique for a Jewish youngster because her father was an Air Force colonel. She lived in many places, including a year in Israel on aA voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz. Like many women photographers, she began as a painting student (in the 1960s, at the San Francisco Art Institute) but was seduced by the immediacy of photography. In 1991, she was the second living photographer ever to be featured in an exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C

Advertising

Foto Ringl + Pit was the name of a photographic studio founded in 1930 in Berlin by Ellen Auerbach and Grete Stern, which produced witty, prize-winning, avant-garde advertising work. As Juan Mandelbaum’s film on the studio reveals, Ringl + Pit was a name derived from the photographers’ childhood nicknames: Pit for Auerbach and Ringl for Stern. (Their last names, they believed, sounded too much like a firm of Jewish merchants). The two, raised in bourgeois Jewish homes in Germany, rejected the constraining values of their families. They studied photography with Bauhaus Professor Walter Peterhans, adopted a bohemian life-style, and came to epitomize the “new woman”—that is, they were emancipated, independent women who cropped their hair, wore trousers, took lovers, and answered only to themselves.

Auerbach (who lived in New York City and died there on July 30, 2004) and Stern (who lived in Argentina and died in Buenos Aires on December 24, 1999.) have recently been “rediscovered” and are enjoying much critical and scholarly attention. Although they won advertising assignments and worked on other artistic projects, their collaboration had only limited commercial success, probably because of their avant-garde style and lack of interest in business. One of their prize-winning photographs advertises the hair lotion Petrole Hahn (1931). Typically, it employs props and features a female mannequin, whose creamy skin, cupid mouth, kohl-rimmed eyes, and simpering smile are obviously artificial. The dummy’s eyebrows and wavy stylish wig, however, are made of human hair, and the hand that displays the lotion bottle belongs to one of the photographers. This surreal blend of reality and fantasy startles at first, then coaxes the viewer toward deeper philosophical musings.

Documentation - Formal Interests

Alma Lavenson’s (1897–1989) father was a successful businessman, philanthropist, and community leader in the San Francisco area. Reflecting his era’s attitudes, he felt that it was wrong to take a job from someone who needed it and also believed that a working daughter reflected on his ability to support his family. Because her father disapproved of women working if they didn’t have to, it is no wonder that Lavenson consistently referred to herself as an amateur, and after her marriage in 1933 continued to think of photography only as an avocation. Her work is unique in that she concentrated on industrial and architectural themes, subjects traditionally favored by men. Interested mainly in formal design, textural elements, and tonalities, she did studies of dams (“Calaveras Dam II,” 1932) and dying or defunct mines and mining towns. In the 1920s and 1930s, “Precisionists” Charles Sheeler, Niles Spencer, and others, whose work Lavenson may have known and certainly was in sympathy with, also favored machine imagery and sharply defined, clearly rendered compositions.

Documentation - Social and Anthropological

Helen Levitt (1913-2009) was a native New Yorker. Born and raised in the Italian-Jewish Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn (her father was Jewish, her mother Italian), she long lived in Manhattan. Her best-known pictures were produced in the 1940s, when she combed the streets, generally of poorer neighborhoods, catching her subjects unawares—especially children at play. Her work celebrates the inventiveness and spontaneity of childhood. Her black-and-white photographs have repeatedly been described as lyrical documents of city life, and while they may stir nostalgia for a less complex time, her work was emphatically realistic and non-idealized. She seems to have shared with Ben Shahn (an acknowledged influence, along with Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans) not only a strong social consciousness and sympathy with working people and their offspring but also an aesthetic inclination for dramatic cropping and empty or decaying urban landscape.

Although Sandra Weiner (1921-2014) was born in Poland, she immigrated to the United States with her parents in 1938. Weiner shared Levitt’s interest in taking photographs of generally poorer city children at play in the city’s streets. She also wrote books for children, illustrating them with her photographs (It’s Wings That Make Birds Fly).

Lynne Cohen (b. 1944) seems as much a cultural anthropologist as a photographer, but it isn’t people she scrutinizes—only their environments and artifacts. Her photographs reveal what strange, amusing, and sometimes haunting places these environments are—lobbies, waiting rooms, beauty parlors, pools in health spas, classrooms, shooting ranges, and labs of all kinds. But Cohen is an artist, not a scientist, and she has no compunction about moving the odd chair or hat rack to make her constructions more effective or evocative. She is sensitive to textures, and her generally large-scale, sharp black-and-white images have strongly defined horizontals and verticals. She also frames them in “real” marbled Formica. So clear is this photographer’s vision and imagery that a particularly sterile or pathetically “enhanced” public place is now sometimes thought of as “a Lynne Cohen place.”

Rosalind Solomon (b. 1930) has traveled widely to document exotic cultures. Sandi Fellman (b. 1952) is likewise interested in remote places. She published a book, The Japanese Tattoo (1986), about the tattooed body. One particularly winning image, “Horiyoshi III and his son” (1984), is of a cherubic, smiling golden-skinned infant held by his father. So as not to distract from the child and the dense and gorgeously tattooed chest of his father, only the man’s torso and hand are visible—all else has been cropped.

Lauren Greenfield is among the younger and talented social documentary photographers working today. In a very interesting recent project, she studied the rites of passage of teenagers in Southern California. Her print “Ashleigh, 13, weighs herself the morning of her bat mitzvah” (1995) speaks volumes about budding girls, American society’s obsession with weight, and the lurking horror of anorexia. A lovely young girl, waif-thin and elegantly dressed in black with pearls, is seen standing on a scale in a very well-appointed bathroom. As she solemnly stares down at the scale’s pronouncement, her robed parents hover in the doorway and a sister sits on the edge of the whirlpool, also anxiously awaiting the results. Greenfield, who grew up around Santa Monica, knows the life-styles and rituals of affluent teens. Her sensitivity to social and psychological issues is probably “inherited” from her mother, a professor of psychology. The photographer herself studied anthropology and photography at Harvard.

Reportage —Taboo Subjects

Documentation and photojournalism imply a certain neutrality and emotional distance, but it is unlikely that the work is ever completely objective—a photographer’s involvement with and attitude toward a subject, however subtle, is always present. Jewish American women photographers—including Lisette Model, Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, and Merry Alpern—occupy an important place in the tradition of sociological reportage that examines intense, disturbing, even shocking subjects.

Lisette (Stern) Model (1901–1983), born in Vienna to a cultivated and prosperous family, studied her first love, music, with Arnold Shönberg. She took up photography later in Paris only “as a way to make a living.” Her mordant view of her fellow human beings was already evident in a suite of her early prints called Promenade des Anglais (1934–1937). Her unsuspecting bourgeois subjects lounging on the boardwalk at Nice seem transformed into a gallery of freaks—self-indulgent, ridiculous, and alone. Among her later work in New York (where she immigrated with her husband, painter Evsa Model) are shots of people who function far outside society’s norms: dwarfs, the obese, transvestites, and derelicts.

Diane Arbus (1923–1971) studied with Lisette Model, and like her teacher was born to wealth (her family owned Russeks Furs). She, too, was fascinated by freaks and by the freakishness in all of us. Freaks reminded her of fairy-tale characters who stopped passersby and demanded an answer to a riddle. As she explained to Janet Malcolm, she saw them as life’s “aristocrats” because they had already “passed their test in life”—they were born with some terrible trauma that other people constantly fear may befall them. She succeeded in presenting images (transvestites, the mentally retarded, twins, triplets, celebrities—Mae West and Norman Mailer, for example) that “nobody would see” unless she photographed them. Considered one of the century’s preeminent photographers, Arbus achieved what most artists only aspire to—she expanded collective perceptions of the world

Nan Goldin (b. 1953), called “a Piaf with a camera,” also documents those who live on life’s margins. The difference in her work, however, is that she records her own world. She and her circle—artists, transsexuals, drag queens, and lovers of both sexes, some people wasting with AIDS—are often caught in particularly vulnerable moments (she photographed herself, eyes bloodied, after having been beaten by a boyfriend). Emotionally fragile and disconnected, all her subjects seem to suffer. Few (her parents excepted) ever laugh or smile, and most are shot in vivid warm tones and exclusively in interiors; bars, bedrooms, and bathrooms seem their natural habitat. An Edward Hopper sensibility haunts Goldin’s work. Despite proximity and yearnings, her subjects cannot seem to connect. In her book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, the photographer states her fear that “men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other, irreconcilably unsuited.” Goldin’s work has been influenced by photographers Weegee, August Sander, and Diane Arbus. In late 1996, the Whitney Museum mounted a much discussed exhibition of Goldin’s work. According to an article in the New York Times, fashion photography of the 1990s (for example, ads for Calvin Klein) has appropriated the documentary-style realism of Goldin and others, and brought the “transgressive fringes into the mainstream.”

Merry Alpern (b. 1955) earned a degree in sociology, which may help explain her interest in documenting the flotsam of the urban environment. Concerned about, but also fascinated by, the homeless, she “started hanging out” with a couple she had observed on the traffic islands of Manhattan’s Upper West Side and began to record their lives. The woman, AJ, was a hooker and an addict; her companion (not lover) was Jim Bob. Alpern asked and got AJ’s permission to photograph her at work. As the photographer explained to Simi Horowitz, she was willing to put herself in such taboo and possibly dangerous situations because, like Arbus, she felt that her camera was in some strange way a sort of shield: It functioned as a kind of barrier between her and her subjects.

Alpern has documented women in prison, teenagers, the physically disabled, and mountain people. More recently, with a zoom lens, she has photographed exchanges between upscale clients and anonymous prostitutes at a sex club in the Wall Street area. The series, shot over a six-month period across an air shaft and through a dirty window divided into four panes, is curiously unsexy. Nevertheless it became a sort of cause célèbre. When Alpern submitted fifteen pieces from the series as part of a National Endowment for the Arts grant application, her application was rejected. Conservative congressional forces were outraged that government monies were being spent on what they considered smut (the work of Alpern and others).

Expressionists

Judith Golden (b. 1934) combines media (paint, graphite) and various printmaking techniques to create powerful, expressive images that often center on woman, her various masks, personas, and powers. At times, she paints (with theatrical makeup and metallic pigments) and powders her models before photographing them. Likewise, Nina Glaser manipulates media and alters her models before creating photographic “staged” tableaux. In one work (untitled) she conjures up visions of the dead and dying in concentration camps. Nude models, who have been coated with a muddy white substance, lie in constructed cubicles. Only their shoulders and heads, tilted at disconcerting angles, can be seen. Like grotesque mannequins, they seem wooden, deathly.

Historically, women have been excluded and marginalized. Artistic and talented women are particularly sensitive to their restrictions and to the attitudes from which they arise. This has affected the sort of subjects and work they decide to tackle. Women photographers, like women artists in general, have been insufficiently studied. Only recently have their contributions begun to be acknowledged in books, exhibitions, and scholarly essays.

Als, Hilton. “Unmasked.” The New Yorker (November 29, 1995): 92.

Bosworth, Patricia. Diane Arbus: A Biography (1984).

Cohen, Lynne. Lost and Found (1992), and Occupied Territory (1987).

Dater, Judy. Cycles (1992).

Dater, Judy, and Jack Welpott. Women and Other Visions (1975).

Ehrens, Susan. Alma Lavenson (1990).

Enyeart, James, L. Judy Dater: Twenty Years (1988).

Fellman, Sandi. The Japanese Tattoo (1986).

Goldin, Nan. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1986).

Nan Goldin: I’ll Be Your Mirror (1996).

Gover, Jane. The Positive Image (1988).

Hogan, Charles. “Annie Leibovitz.” Art News (March 1990): 91–95.

Helen Levitt (1980).

High Heels and Ground Glass: Pioneering Women Photography. Video, written and produced by Deborah Irmas and Barbara Kasten (c. 1990).

Horowitz, Simi. “Life on the Street.” American Photographer (July 1989): 79.

Lavin, Maud. “Ringl and Pit: The Representation of Women in German Advertising, 1929–1937. The Print Collector’s Newsletter 16, no. 3 (1985): 92.

Lisette Model (1979).

McEven, Melissa A. “Doris Ulmann and Marion Post Wolcott: The Appalachian South.” History of Photography 19, no. 1 (1995): 5.

Malcolm, Janet. “Aristocrats.” The New York Review of Books (February 1, 1996): 7.

Meyerowitz, Joel, ed. Street Photography (1994).

Mitchell, Margarette. Recollections: Ten Women of Photography (1979).

Morath, Inge. Portraits (1986).

Naef, Weston. The Collection of Alfred Stieglitz: Fifty Pioneers of Modern Photography (1978).

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day (1982).

Orkin, Ruth. Ruth Orkin: More Pictures from My Window (1983).

Ringl and Pit. Video, produced and directed by Juan Mandelbaum (1995).

Rosenblum, Naomi. A History of Women Photographers (1994).

Solomon, Rosalind. Portraits in the Time of AIDS (1988).

Sontag, Susan. On Photography (1978).

Spindler, Amy. “Nineties’ Attitude: Visual and Raw.” NYTimes, November 26, 1996.

Sullivan, Constance. Women Photographers (1990).

Thomas, Ann. Lisette Model (1990).

Tucker, Anne, ed. The Woman’s Eye (1973).