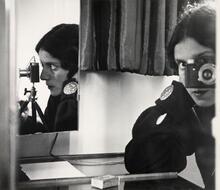

Doris May Ulmann

A photograph of an Appalachian woman, titled Old woman in sunbonnet, no. 2 by photographer, co-founder of the Pictorial Photographers of America, and philanthropist, Doris May Ulmann (1882–1934).

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Expert photographer Doris May Ulmann captured both the celebrities of her day and the rural poor of Appalachia with what the New York Times described as “haunting power.” Ulmann earned a teaching degree from the Ethical Culture School in 1903 and studied at the Clarence White School of Photography. She published three volumes of photos of doctors, but after divorcing her surgeon husband, she shifted her focus, capturing the Appalachian poor, Mennonites, Shakers, black plantation workers, as well as modernist celebrities. While on a trip to Appalachia in 1934, she fell ill, dying soon after her return to New York. She endowed the John C. Campbell Folk School in North Carolina and the Doris Ulmann Collection at Berea College in Kentucky.

One of America’s most accomplished but enigmatic pictorialists, Doris Ulmann is often mistakenly hailed as a pioneering documentary photographer. Ulmann’s interest in folk archetypes, her tableaux portraiture of impoverished rural Americans, and her life-long affiliations with Progressive Era institutions suggest that she never transcended her Victorian class biases. As a critic once described Ulmann’s significance for the New York Times: “It is the tension between her romantic vision and these little unintended bits of the present that give her photographs their haunting power.

Early Life and Education

Born May 29, 1882, on New York City’s Upper East Side, Doris May Ulmann was the second daughter of Reform Jewish parents, Gertrude (Maas) and Bernhard Ulmann, a German immigrant who amassed a fortune in America as a woolen manufacturer. As members of the Ethical Culture Society of New York, the Ulmann family embraced a nonsectarian faith in secular humanism, a sensibility reflected in Doris Ulmann’s later choice of destitute black southerners and Appalachian mountaineers as portrait studies.

In 1903, Ulmann received a teaching degree from the Ethical Culture School. She is said to have studied law and psychology at Columbia University, though no record exists of her enrollment there. She is listed as a student in the Clarence White School of Photography during the years of the First World War. White, a co-founder in 1902 with Alfred Stieglitz of the Photo-Secession, a select group of pictorialists committed to establishing photography as a fine art form. Inspired by the Impressionist painters, pictorialist photographers used large-format view cameras and soft-focus lenses to lend a painterly, dreamy quality to their idyllic landscapes and portraits. So dedicated was Ulmann to Clarence White and the pictorialist genre that she and her surgeon husband, Charles H. Jaeger, joined him as co-founders of the Pictorial Photographers of America shortly after the end of World War I.

Photography Career

From 1920 to 1925, Ulmann augmented her Victorian oeuvre with three published volumes of photos of prominent physicians and magazine editors, but her divorce from Jaeger seems to have marked a turning point in her career. Ulmann’s first photographs of rural Mennonites, Shakers, and mountaineers appeared in The Mentor in 1927 and Scribner’s in 1928, while her portraits of such modernist giants as Ansel Adams, Albert Einstein, Martha Graham, Edna St. Vincent Millay, José Orozco, and Thornton Wilder were carried by Bookman, Vanity Fair, and the gravure sections of Sunday newspapers.

During the late 1920s, Ulmann befriended the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Julia Peterkin, who invited her to photograph a large community of African-American laborers living at Lang Syne, Peterkin’s South Carolina plantation. From 1929 to 1932, Ulmann photographed black southerners there and in coastal Alabama and Louisiana, producing what may be the most extensive documentation of the southern plantation. When asked in 1931 by Allen H. Eaton of the Russell Sage Foundation to photograph native craft production in Appalachia, Ulmann hired Kentucky balladeer John Jacob Niles to assist with the transport of her cumbersome equipment and heavy glass plates.

She fell ill while working in the North Carolina mountains during the summer of 1934 and died shortly after her return to New York City on August 28. Doris Ulmann endowed the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, North Carolina, and established the Doris Ulmann Foundation at Berea College, Kentucky.

AJYB 37:262.

The Appalachian Photographs of Doris Ulmann (1977).

Attille, Martina. “Still,” in Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance (1997); Banes, Ruth A. “Doris Ulmann and Her Mountain Folk.” Journal of American Culture 8 (1985): 29–42.

Coles, Robert. The Darkness and the Light: Photographs by Doris Ulmann (1974).

Contemporary Photographers (1982).

Davis, Keith F. An American Century of Photography (1995).

Doris Ulmann: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (1996).

Eaton, Allen H. Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands (1937).

Featherstone, David. Doris Ulmann, American Portraits (1985).

Hagen, Charles. “Rural Social Commentary with a Difference.” NYTimes, November 4, 1994.

Lamuniere, Michelle C. “Roll Jordan Roll and the Gullah Portraits of Doris Ulmann.” History of Photography 21 (Winter 1997).

Lovejoy, Barbara. “The Oil Pigment Photos of Doris Ulmann.” Master’s thesis, University of Kentucky, 1993.

Obituary. NYTimes, August 29, 1934.

McEwen, Melissa A. “Doris Ulmann and Marion Post Wolcott: The Appalachian South.”History of Photography 19 (Spring 1995).

Naef, Wetson, ed. Doris Ulmann: Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum. In Focus Series (1996).

Rosenblum, Naomi. “Documenting a Myth,” in Documenting a Myth: The South as Seen by Three Women Photographers: Chansonetta Stanley Emmons, Doris Ulmann, Bayard Wooten, 1910–1940, exhibition catalogue (1998).

Ulmann, Doris. Collection of African-American studies and artist portraits. New-York Historical Society, NYC.

Photographs. Berea College, Berea, Kentucky.

Proof prints. University of Oregon, Eugene.

Warren, Dale. “Doris Ulmann, Photographer-in-Waiting.” Bookman 72 (October 1930): 129–144.