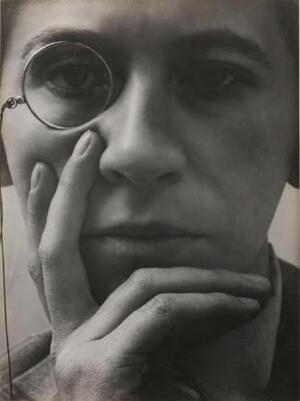

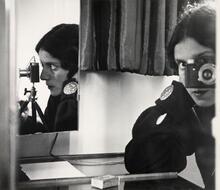

Aenne Biermann

Self-portrait of photographer Aenne Biermann, 1928.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In her short life, self-taught photographer Aenne Biermann made a profound impact on the arts as a major proponent of “new objectivity,” a rejection of romantic idealism in favor of practical engagement with the world. Frustrated by the work of traditional portraitists, she taught herself photography to better capture her growing children. She experimented with other subjects, producing her most important works between 1926–1932. She explored nature, the quality of light shining on metal utensils, and even captured the precise structures of minerals for geologist Rudolf Hundt. Her works were part of every major exhibition in Germany at the time. Due to the rise of Nazism soon after her death, only four hundred prints remain of the thousands of negatives she created.

Writing in 1929 about her development as a photographer, Aenne Biermann stated: “I realized ever more clearly that the lighting was of critical importance for the clarity of the work. … The effect of light on the polished surface of a metal utensil, a play of shadows seldom noticed, surprising contrasts of black and white, the problem of achieving a happy spatial arrangement in a picture, created inexhaustible surprises.” This “intimacy with objects” and the effort she invested in coming into close contact with everyday objects remain characteristic of Biermann’s work.

Early Life and Family

Anna Sibilla (Aenne) Biermann was born in Goch on the Lower Rhine, where her father Alfons Sternfeld (1865–1928) had taken over the leather factory founded by her grandfather Wolfgang in 1855. Aenne’s mother, Julie (née Meck), was born in 1868 and died in 1927. Aenne’s husband, Herbert Joseph Biermann, a prosperous textile merchant and art lover, whom she married when she was twenty-two, was also born in the Lower Rhine area. His father, Max, was a founding member of the Jewish community in Goch, together with Hermann Tietz. In 1920 Aenne and her husband moved to Gera, a center of progressive German culture, where the couple’s children, Helga (b. 1921) and Gershon (Gerd, b. 1923), were born.

Photography Career

It was her children who prompted her to take to photography in 1921, at first as a recorder of “private souvenirs,” later in profound disagreement with the conventional “portrait technicians.” Her major works were created between 1926 and 1932, a period during which she worked obsessively, participating in numerous exhibitions: in 1929 at the Kunstkabinett in Munich (one-woman show), Essen (Contemporary Photography) and Stuttgart (Film and Photo); in 1930 again in Munich (Photography); in 1931 in Basel (New Photography); in 1932 in Brussels (Internationale de la Photographie). At the same time her photographs appeared in international art and photography magazines. Following her early amateurish attempts at child photography, Biermann’s subjects included photos of minerals and crystals and close-ups of flowers and plants. She looked carefully at “living forms, such as flowers, leaves and plants,” based on the “partially architectonic structure,” the reproduction of which she considered best suited for photography. In this, she was following her own interest in natural science and also the stimulus provided by Rudolf Hundt, the geologist who in 1927 asked her to prepare “very precise photographs” of minerals for his scientific work. In 1929 there followed photographs of household utensils. A desire to extract something unfamiliar from everyday experience combined with her technical photographic equipment and the optical/chemical possibilities of development in the laboratory. Self-taught, Aenne Biermann worked in relative isolation, deriving her distinct tendency towards innovative photography primarily from professional journals and books. Nevertheless, her works were displayed in all the international photography exhibitions of the late 1920s and early 1930s, alongside those of Lucia Moholy, Florence Henri and Germaine Krull.

“Her working day was too short and the fact that she worked far into the night in her darkroom, developing and enlarging, may have sown the seed of her severe illness.” This was geologist Rudolf Hundt’s opinion regarding the intensive phase of creativity of his friend Biermann, in the 1920s. Shortly afterward she died of a liver ailment at the premature age of thirty-five. She was thus spared persecution by the National Socialist regime, though her family was less fortunate. Of the three thousand or so negatives she made, approximately four hundred prints survive.

Biermann, Aenne. Fotografien 1925–1933. Berlin: 1987 (exhibition catalog).

Hundt, Rudolf. “Zum Gedenken an Aenne Biermann.” Geraer Kulturspiegel 4 (1947).

Roh, Franz. “Fotos von Aenne Biermann.” Das Kunstblatt (12): 1928, 306.

Lexikon Jüdische Frauen. Edited by Jutta Dick and Marina Sassenberg.