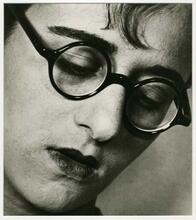

Ellen Auerbach

Ellen Auerbach was remarkable both for her avant-garde photography and for her innovative and successful ringl+pit studio, where she and fellow artist Grete Stern signed all their work collaboratively. Auerbach met Stern in 1929 when both were private students of Walter Peterhans, Master of Photography at the famed Bauhaus School for art and design. Auerbach fled to Palestine in 1933, where she supported herself in making short films to promote Israel and opened a studio specializing in photographing children. In 1937, she moved to the United States, where she worked again as a children’s photographer and collaborated with a child psychologist on short films on children’s behavior. In the 1950s, she slowly lost interest in photography and shifted to working as an educational therapist with learning-disabled children.

The life of Ellen (Rosenberg) Auerbach was a constant journey of self-discovery and, in her photographic work, a search for the essence that lies behind people and things. Her curious mind, her keen and intuitive eye, and her sense of humor permeated her photography, which was re-discovered in the late 1970s, along with that of other avant-garde photographers and artists of the Weimar Republic. Auerbach belonged to the generation of New Women who sought to break with traditional female roles and become independent through their work.

While riding on the crest of the avant-garde photographic trends of the late 1920s, Auerbach developed her own distinctive style, which corresponded with her constant need to find the “essence behind things.” Her wonderful intuition, her “third eye,” allowed her to capture atmospheric moods that went beyond the subjects she photographed.

Early Life and Family

Ellen Rosenberg was born on May 20, 1906, in Karlsruhe, Germany, the daughter of Max Rosenberg and Melanie Gutmann. An older brother died when he was a child. Her brother Walter was born twelve years later. The Rosenberg family enjoyed a comfortable life in which the parents filled traditional roles: her father was a successful businessman, while her mother looked after the family and social life. From an early age Ellen wanted to become independent. Seeing that she had no interest in the family business, her family allowed her to study but provided little financial or emotional support. Between 1924 and 1927 Rosenberg studied art at the Badische Landeskunstschule in Karlsruhe under professors Paul Speck and Karl Hubbuch and in 1928 continued her studies at the Academy of Art (Am Weissenhof) in Stuttgart. She recalled visiting a house designed by the renowned French architect Le Corbusier, which was raising the ire of local people for daring to have benches come out of the walls. An uncle for whom she had done a bust gave her a 9 x12 cm camera and thus she discovered photography. Rosenberg thought that this new medium would be a better way to make a living than creating sculptures.

Berlin and Early Career

In 1929 she moved to Berlin to study photography with Walter Peterhans, who had been recommended by a friend for his excellent photographs and jazz record collection. At his studio, Rosenberg met Grete Stern, Peterhans’s only other private student. Ellen and Grete began a profound friendship that lasted throughout their lives. He taught them his exacting techniques about light and composition. Berlin was a thriving arts and cultural center and a place where young women could live free lives without having to worry about what their families would think. But they had few models to follow. For Ellen Rosenberg, the move to the capital was the beginning of a final rupture from her bourgeois background and from her family’s traditional expectations for her. In Berlin women could wear trousers, smoke in public, cut their hair short, and live free social and sexual lives—all emblems of the New Woman. They were exposed to new films by directors such as René Clair and theater pieces like Brecht’s The Three Penny Opera.

Rosenberg had only a short period of lessons with Peterhans, because in 1930 he was named Master of Photography at the renowned Bauhaus School for art and design in Dessau. But the lessons had a deep influence on the women, who were able to understand through Peterhans that photography could be an art form, just like painting or sculpture. This was a novel idea at a time when photography was used primarily for illustration.

Collaboration with Grete Stern

Using the proceeds from an inheritance, Stern bought Peterhans’ equipment and with Rosenberg established a photography studio to do advertising, fashion, and portrait photography. Since “Rosenberg and Stern” sounded too much “like a Jewish clothes manufacturer”, they called the studio ringl+pit, after their childhood nicknames (ringl for Grete, pit, an abbreviation for Pepita, a dancer Ellen resembled). At the time it was quite unusual for two young women to start a business. They decided to sign all their work together, which was also unique. The two young women also lived together in their studio.

In the early 1930s, modern advertising was at its beginnings and left ample room for creative exploration. ringl+pit’s advertising work represented a departure from current styles by combining objects, mannequins, and cut-up figures in a whimsical fashion. Stern and Rosenberg were also influenced by the intense creative environment current in Berlin at the time. Their work explored a new way of portraying women, also in character with the image of the New Woman that was emerging. There was a subtle irony in their work about what was accepted and expected of women that was a marked departure from the dominant image of women. Grete’s specialty was in graphic design and she was more interested in the formal aspects of photography. Ellen provided the more subtle, humorous, and ironic touches that challenged the traditional representations of women in advertising and films. Their very different personalities were able to emerge in a small body of work that was starting to become recognized at the time. As Ellen explained, “We are very different people. She is more serious than I am. I’m a frivolous person. But we had a lot of fun together. She was serious and I frivoled.”

Initially, they received few commissions, sporadically aided by the Mauritius agency. They also photographed friends and lovers whom they met through bohemian circles. These included the dancer Claire Eckstein and her friend Edwin Denby, the poet Marieluise Fleisser and a set designer, Walter Auerbach.

In 1931 ringl+pit’s work received positive reviews in the magazine Gebrauchsgraphik and in 1933 they won first prize for one of their advertising posters at the Deuxième Exposition Internationale de la Photographie et du Cinéma in Brussels.

However, in April 1930 Grete Stern followed Peterhans to Dessau to continue her studies. There she met an Argentine photographer and fellow Peterhans student, Horacio Coppola. Ellen kept the studio running and Stern returned to continue their work together in March 1931. Stern went back to the Bauhaus for further studies with Peterhans between April 1932 and March 1933. Walter Auerbach started to visit the ringl+pit studio and occasionally also lived there with the two women. In 1932 Ellen went to live in Walter’s small attic apartment.

Ellen, who also experimented with film, made two short black and white films. Heiterer Tag auf Rügen was an experimental film that mixed elements of nature with images of friends on a visit to the island of Rügen. The short silent drama Gretchen hat Ausgang features Grete playing a maid who meets a handsome man (played by her future husband Horacio Coppola) who tries to seduce her at the local ice-cream parlor.

Move to Palestine

When Hitler rose to power in 1933, Walter Auerbach, who was active in leftist political circles, warned the women of the dangers ahead. Ellen and Walter left their apartment and fled to the countryside. Aware of the increasing political repression, they decided to leave Germany. Palestine was the only place Ellen could go to, thanks to a loan from Grete that allowed her to enter as a “capitalist.” At the end of 1933, Ellen emigrated to Palestine and Grete left for London. Shortly after her arrival, Ellen made Tel Aviv, a 16mm black and white film about the growing city, for the WIZO organization. But these commissions to promote a Jewish Palestine were thematically and personally far from her interests. Walter Auerbach also went to Palestine and in 1934 they opened Ishon (“apple of my eye”) in Tel Aviv, a studio specializing in children’s photography. At the same time Ellen started photographing everyday life in Palestine. This took her out of the studio and into the streets and villages. She was greatly affected by the difficulties in coexistence between Arab and Jews.

In 1936, with the outbreak of the Arab revolt, the studio’s commissions declined. Walter and Ellen, who had not adapted well to life in Palestine, left for London to visit Grete. Once again Grete and Ellen collaborated in a few commissions, notably one for a maternity hospital. This would be their last work together. In London they also met Bertolt Brecht, whom they both photographed. Ellen made a short film of Brecht reciting his poetry so that future generations would see how he read his poems. The only problem was that the film was silent.

By this time their styles had changed, with Grete continuing the formal style learned with Peterhans and Ellen becoming much freer and less preoccupied with technical perfection. Grete emigrated to Argentina that year. Ellen tried to continue with the London studio but was unable to obtain a work and residency permit.

The United States and Work with Children

In 1937 Ellen married Walter Auerbach in order to emigrate to the United States on one visa, thanks to an affidavit they had received through a distant relative of Ellen’s. They lived first in Elkins Park, a suburb of Philadelphia, where Ellen continued to work as a children’s photographer in order to make a living. In 1938 one of her child photographs was selected for the cover of Life Magazine’s second-anniversary issue. Between 1939 and 1942 she documented artworks for the Lessing-Rosenwald art collection and experimented with infra-red and ultraviolet light and with Carbro printing.

Meanwhile her brother Walter Rosenberg had managed to secure a visa for Argentina in 1936 and sailed there to live with Grete Stern, who had married Horacio Coppola. The Rosenbergs’ parents stayed behind in Karlsruhe. In 1941 they were interned by the Germans at the Gurs concentration camp in France, from where they were freed in 1943 by American troops. At the end of the war they returned to Karlsruhe—a most unusual move for Jewish survivors.

In 1944, after Walter was drafted, Ellen Auerbach moved to New York, where they were introduced to the bohemian avant-garde, among them Willem de Kooning, whom Auerbach photographed, and Fairfield Porter, a painter who would become a close friend. Ellen and Walter were separated in 1945, but remained friends. She kept his name. Ellen started visiting Great Spruce Head Island in Maine, the Porter family’s summer place, where she continued her art photography, focusing on nature subjects and people on the island. All of them done with available light, these might be Porter family members or maids working at the house. Between 1946 and 1949 Ellen Auerbach worked with Dr. Sybil Escalona, a child psychologist, at the Menninger psychiatric institute in Topeka, Kansas. There she photographed and made two films on young children’s behavior. In 1946 she also traveled to Argentina to visit her brother and Stern, and to Greece, Mallorca (to visit Walter Auerbach), Germany and Austria

Later Photography

At this point photography was no longer a professional endeavor but rather a way to search for deeper meanings in life and in people, a lifelong quest of hers. She wanted to show the essence of things, whether of a tree or of a child. She called her way of finding this essence the “Third Eye,” which would capture that which lies beneath the surface of things. Auerbach continued to travel extensively between the 1940s and 1960s, photographing landscapes and nature, as well as interiors, architecture, street scenes, and portraits. As she explained in a 1992 interview, “It’s a zen question. I think that to make a photograph, the way I liked to, you have to be so completely absorbed in what you are photographing that you forget yourself, and become what you photograph. And not stand there and say: ‘now I’m making a photograph.’” She continues, “If you photograph something that you are forced to photograph, it cannot go over. You have to feel great enthusiasm or pity or whatever it is for what you are doing—and then it seems to transmit this in all kinds of shapes. Sometimes I don’t even understand why I photograph something. And when it has that effect on people, I think, at least inside of me, I must have felt the same way.”

In 1954 she went to Great Spruce Island to visit nature photographer Eliot Porter, whom she had met through his brother Fairfield. He asked her to accompany him on a trip to Mexico to photograph churches. They went there in 1955–1956. Because Auerbach and Porter were interested in portraying the atmosphere around the objects, the photographs were taken with natural light, sometimes only with candle light, which was unusual at the time. Most were in color. Auerbach also took a number of black and white photographs. When they returned they tried to interest publishers but it was not until thirty years later that their work received recognition. Mexican Churches was published in 1987 and Mexican Celebration in 1990. After the Mexico trip Eliot Porter told Ellen that he now photographed differently and better, but for her it was the opposite. She no longer wanted to photograph and gradually stopped taking pictures. “Maybe one reason is that I don’t think that you have to do the same thing forever. I had been a photographer for thirty-five years. In that time you start something new. I even today think that I should start something new,” she explained in 1992, when she was eighty-six years old.

Educational Therapist Work and Legacy

At the age of sixty Auerbach embarked on a new career: until 1984 she worked as an educational therapist with children with learning disabilities at the Educational Institute for Learning and Research in New York. She photographed only occasionally. Even though she had no training as a psychologist or therapist, Tate Schmidt, the institute’s director (whom Ellen had met briefly in Palestine), gave her training and opportunities. She used her keen insight and intuition to work with the children to find ways to cope with their problems and had a very high success rate despite the lack of formal training. She crafted a space where children were able to explore themselves and find out about themselves in ways that they never had before. Years later many of the children would come to visit her and remained friends.

From the 1980s the work of ringl+pit and that of Ellen Auerbach and Grete Stern was “rediscovered” as German museums started to look back and find these gems of their past still alive and ready to serve as role models to a new generation. Ellen’s hometown organized a show in 1988 called Emigriert. The Folkwang Museum in Essen mounted a comprehensive ringl+pit exhibition in 1993 and many others followed. For Ellen the culmination was a retrospective of her work at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1998. Ellen Auerbach took the accolades in stride. “These pictures are an expression of that time, although we did not consciously think about women and this and that, but it was in the air. It is always like that, that something does not happen in one single case. What we did then is now admired as the ‘forerunners’ of something. First of all, when you’re running you don’t know that you’re running ‘fore,’ but the modernity of those pictures was because the time was a breakthrough time.”

Ellen Auerbach died in New York on July 30, 2004, at the age of ninety-eight.

Buchloh, Benjamin HD. “Photography's Exiles: from Painting, Patriarchy, and Patria.” October (2020): 3-6.

Eskildsen, Ute, Jean Christophe Ammann, Renate Schubert, and Susanne Baumann. Ellen Auerbach: Berlin, Tel Aviv, London, New York. Prestel, 1998.

Keller, Judith, and Katherine Ware. “Women photographers in Europe 1919-1939: An exhibition at the Getty Museum.” History of Photography 18, no. 3 (1994): 219-222.

March, John. “3 Women Exile Photographers 49.” In Applied Arts in British Exile from 1933, pp. 49-66. Brill Rodopi, 2019.

Otto, Elizabeth. “ringl+ pit and the Queer Art of Failure.” October (2020): 37-64.

Porter, Eliot, and Ellen Auerbach. Mexican churches. University of New Mexico Press, 1987.

Roth, Helene. "Ellen Auerbach." METROMOD Archive, 2021, https://archive.metromod.net/viewer.p/69/2948/object/5138-10770030