Photography in Palestine and Israel: 1900-Present Day

Although women photographers long struggled for recognition and appreciation in Palestine and Israel, in recent years awareness of their roles and contributions to photograph has increased. The activity of women photographers who focus on gender issues has increased dramatically, while female curators and academics are gaining new perspectives on Jewish female photographers, re-evaluating their role in the development of photography in Israel. In the pre-state period, many women photographers were immigrants from Germany who brought new training and techniques. By the 1970s, photography was newly perceived in Israel as an important mode of expression. Over the last several decades, the male-dominated nature of the field has begun to change as female photographers produced innovative portraits, landscapes, socio-politically oriented photography, and conceptual art.

Introduction

Women photographers have always struggled for recognition and appreciation in Palestine and Israel. Historically, photography was primarily used to document the Zionist enterprise in Palestine, and photographers assumed the responsibility of expressing its history, the people, and the land. Until the late 1970s, most photography in Israel was used for recording facts, in contrast to much of the Western world, where photographers were busy exploring the medium’s artistic possibilities. In recent years awareness of women’s roles and contributions to photography has increased, due to the growing number of highly qualified female photographers, curators, and academics. The activity of women photographers who focus on gender issues has increased dramatically, while female curators and academics are gaining new perspectives on Jewish female photographers, re-evaluating their role in the development of photography in Israel.

Photographs by women in Palestine developed concurrently with the evolution and growth of the country itself and the changing status of women in Israeli society. Over eleven decades of photographic activity, women photojournalists, portraitists, influential art-world photographers, curators, researchers, teachers, and younger artists created and directed imagined scenes; they worked, exhibited, curated, researched, published, taught, and influenced society from within.

Photography in Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Palestine

From the time of photography’s invention in 1839 through the 1880s, photographs in Palestine were intended for Western audiences and taken mainly by Western photographers, missionaries, gentlemen travelers, tourists, and explorers. Photographers depicted the Holy Land and its sites, archeological ruins, and portraits of the local populations. They intentionally presented local inhabitants as primitive and backward, to suit the Western imperialist and colonial gaze (Graham-Brown). The Western gaze disregarded cultural and urban development in the area, as well as the existence of local Arab, or Armenian photographers. Jewish photography in Palestine began in the early 1880s, with immigrants of the First Lit. "ascent." A "calling up" to the Torah during its reading in the synagogue.Aliyah (1882–1903) from Eastern Europe providing tangible depictions in the form of photographs for their fellow Zionists at home in Europe and the United States.

Early in the twentieth century, two Zionist organizations, founded for the purpose of encouraging the growth of the new country, commissioned photographers to document and further the national agenda. The Jewish National Fund (JNF) was established in 1901 for the purchase and development of land. In 1920 the World Zionist Organization created its financial umbrella organization, Keren Ha-Yesod (Palestine Foundation Fund). The JNF recruited male photographers to document Zionism in the making and to create a utopian vision intended for fundraising. They documented every aspect of life in Palestine extensively in the hope of encouraging fellow Jews around the world to take part in building a homeland for the Jews. Transforming the land, by Jews for Jews, seemed miraculous, and no time was wasted before disseminating evidence of the progress around the world in the form of photographic images. Pioneers were portrayed working the soil and building roads and towns. These images formed a collective vocabulary for the new Zionism, one that endowed the working pioneers with heroic and romantic qualities. The low-angle style of photographing workers and groups of pioneers toiling the and in hard labor was influenced by Soviet Realism (Barromi-Perlman). These images became an integral part of the JNF’s promotional material. At the same time, in order to make a living, some photographers set up private studios where they made portraits of individuals and families.

Jewish Women Photographers in the First Half of the Twentieth Century

Sonia Narinsky’s photographs around 1910 are the first thought to have been by a woman photographer in Palestine. A member of A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Deganyah, the first A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kevuzah established in Palestine, Narinsky had emigrated from Russia around 1905 with her husband Shlomo Narinsky, a well-known and successful painter; they lived in Jerusalem and traveled around the country taking pictures until they were deported to Egypt in 1916, where they established a photo studio in Alexandria for Jewish refugees from Palestine. They eventually returned to Palestine in 1944. Details of Narinsky’s life and activities are unclear, and no photographs have been definitively identified as hers. They are signed as Narinsky or S. Narinsky and mostly attributed to her husband. Historians are divided over the extent to which Sonia was actually involved in picture-taking; one states that during the four years her husband pursued his painting in Cairo she supported him by taking pictures, and that, as a woman, she had access to the harems of the Egyptian elite. She is also said to have been the first to take pictures of Egyptian women without their veils (Gidal and Silver-Brody).

Through the 1920s, photographs in Palestine were typically of landscapes, settlements, immigrants, and working farmers. Stylistically, they were straightforward and purposeful, their aim to promote Zionism and the flowering desert.

By the mid–1930s, the area was home to many artists and photographers fleeing Nazi Germany. They came with sophisticated equipment, training, and an awareness of the various visual and technical experimentations that had taken place in post-World War I Europe and Russia. New angle shots and unusual ways of seeing emerged, and the European immigrants expanded their subjects to include architecture, body parts, and industrial scenes, in addition to landscapes. It was a time of experimentation, abstraction, and a new visual artistic language. The immigrants who came to Palestine with first-hand knowledge of this new genre hoped to be hired by the Zionist institutions to make pictures that would be used for promotional purposes. They quickly discovered that the JNF recruited male photographers to craft photographs of smiling faces of pioneers. There was no room for personal taste or reflection or a humane reflection. During the heyday of the Yishuv, women photographers often worked privately in their homes. They achieved little fame or recognition; some were forgotten, and their archives were discarded. In the little that remained, the choice of subject matter and experimentation with avant-garde style, photograms, and photo-collages makes clear that they were free to create outside the mainstream of Zionist photography.

In 2019, as part of the PHOTO IS:RAEL festival, Eyal Landsman and Guy Raz initiated the Ladies of Photography project to identify female photographers in Israel between 1850 and 1978. They uncovered 110 female photographers who had been forgotten, including Sonia Kolodoni from Photo Sonia (1922-1948), who used her work for self-expression.

In conjunction with Landsman and Raz’s project, visual artist Noa Sadka curated the exhibit “"The Concerned Photographer – ‘And I was Photographing and Crying, Crying and Photographing’” at the PHOTO IS:RAEL festival. Sadka (b. 1967), an art-photographer and teacher who studied at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, exhibited the work of ten female photographers, most from the 1930s and three from later periods: Frieda Mayer-Jacobsohn (1892-1971), Aliza Holz (1895-1991), Lou Landauer (1897-1991), Anna Riwkin-Brick (1908-1970), Chava Salomon (1914-2010), Bettina Oppenheimer (1919-1972), Behira Eden (1933-2015), Naomi Zur (b. 1940), Yael Rozen (b. 1945), and Ronit Shany (b.1950). Some of the women had arrived as refugees or worked under exceptionally trying conditions, photographing between cooking and caregiving, using their kitchen or toilet as their darkroom. Sadka refers to their photography as “humanist, intuitive” work. In her Introduction, she asks, “Why is that I was embarrassed to show a photograph of me changing diapers or breast feeding in the Tel Aviv Museum?” According to Sadka, the women’s photographs—a cat, stars, pregnancy, giving birth, babies, homelessness—had been overlooked by Israeli institutions; their photography was not taught, exhibited, or archived.

Many of these overlooked women photographers had immigrated from Germany. Photographer and documentary filmmaker Lou Landauer, for example, came to Palestine in 1933, worked as a photojournalist and book-cover artist from the 1930s through the 1950s, and was hired by the Keren Ha'yesod to document modern architecture. She became the first photography teacher at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and taught under difficult conditions, mostly from her home. Influenced by her German background, she taught the new style of photography, using experimental and avant-garde photography, photo montages, double exposures, and landscapes. Landauer, whose teaching position was in the graphic arts department, also attempted to create a separate photography department. In 1948, her work at Bezalel was terminated, and her archives and works are unknown or lost.

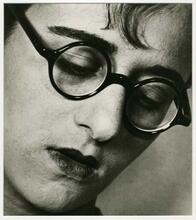

Ellen Auerbach (1906-2004, née Rosenberg), born in Karlsruhe, Germany, studied sculpture before turning to photography and taking lessons in 1929 from important Bauhaus professor Walter Peterhans (1897–1960). The following year she opened a photography studio in Berlin with her friend Grete Stern. Because they thought their own last names sounded too much like a firm of Jewish merchants, they called their studio “foto ringl + pit,” using their respective childhood nicknames: Grete’s was Ringl, Ellen’s Pit. The studio specialized in avant-garde advertising that won them assignments and awards but ultimately was not a commercial success due to their extreme avant-garde style and lack of business acumen. In 1933, Stern immigrated to London and Ellen to Palestine; that same year Auerbach opened a studio in Tel Aviv called Ishon (“pupil of the eye”) to photograph children. By 1936 Auerbach had left Palestine for London, where she took over Stern’s studio. Unable to obtain a work permit, she moved to the United States in 1937. She continued working as a photographer until 1965, when she became an educational therapist.

The sisters Charlotte (1911–1978) and Gerda (1913–1993) Meyer were born in Posen, in eastern Germany, and moved to Berlin in 1921. Their education was overshadowed by the political climate: Gerda was forced to abandon her medical studies at the University of Berlin due to the racial laws, while Charlotte opted to stay out of university and instead experiment with photography. By 1933 they realized they had no future in Germany; at the end of 1934, Charlotte left for Palestine and opened a photography studio in Haifa. Soon after, Gerda also decided to become a photographer, studying with Professor Fritz August Breuhaus (1883–1960) and working as an apprentice in the studio of Arno Kikoler, the official photographer of the Jewish community in Berlin. In 1936 she joined her sister and together they worked in the Haifa photography studio, which rapidly became highly regarded for portrait photographs and attracted an international clientele. Their famous subjects included Arturo Toscanini, David Ben-Gurion, Bronislaw Hubermann, Eugen Schenkar, Chaim Weizmann, Golda Meir, and Moshe Dayan. In the mid–1940s the sisters also pursued industrial photography and were commissioned by the Iraq Petroleum Company to document the building works and refineries in Haifa Bay. This series of modernist photographs emphasized the form of the machinery rather than its function. Gerda left for Canada with her husband and daughter in 1953; the studio remained open until 1957, when Charlotte moved to London.

Other photographers who came from Germany included Lotte Errell, Sonia Gidal (b. 1922), Rachel Hirsch (b. 1937), Aliza Holz (1898–1993), Frieda Mayer Jacobsohn, Bettina Oppenheimer, Ricarda Schwerin, Liselotte Grjebina, and Marli Shamir. Hannah Degani (b. 1917 in Saarbruecken) moved to Italy in 1935 and studied photography until moving to Palestine in 1936 with her family. She was initially a portrait and medical photographer in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. In 1944 she married Ephraim Degani (1912–2001), who had moved to Palestine from his native Berlin in 1933; the couple operated Photo Prisma, the premier photography shop in Jerusalem, located in Zion Square. Degani is best known for her 1936–1937 Tel Aviv series “First Impressions: The Carmel Market,” of which “The Shoe Maker” is one of the most poignant examples.

Bettina Oppenheimer (née Sander, 1919–1972) was born into a Zionist family in Stuttgart. In the mid–1930s her brother became a farmer in Palestine and she joined a group of Germans planning to go to Palestine to work the land. In 1939, she moved to London for agricultural training, joining her brother in Palestine when war became inevitable. After several years of study, she married Dr. Willi Oppenheimer and had little time to pursue photography until two years after the War of Independence, when she trained with Ephraim Degani. She also managed her husband’s office and assisted him in scientific studies that influenced her work. Bettina Oppenheimer experimented with light and color and photograms, ultimately creating many photographs featuring the dandelion—a flower that brought to mind happy memories of her childhood in Germany.

Tzipora David (b. 1882-1936) photographed from within Kibbutz Ein Harod in the early 1930s. Her photographs, which were rediscovered by Guy Raz in 2016, focused on women and children on the kibbutz and reflect a sensitive spirit and personal freedom. She was considered not only a pioneer but also a photographic pioneer. She developed her photographs in a small dark room in an attic above the cow shed. Although the negatives are lost, the photographs remain.

Ricarda Schwerin (née Meltzer, 1912–2001) had a deep interest in photography beginning in childhood. She convinced her father to allow her to study photography in Dessau from 1929 until 1933. While in Dessau, she married Heinz Schwerin; after 1933, they spent two years looking for a new homeland before settling in Palestine in 1935. Together they established a workshop where they made wooden toys. Unable to manage the shop alone after Heinz’s death in 1948, Ricarda returned to her original profession as a photographer in 1956. She met Alfred Bernheim (1885–1974) and developed a close working and personal relationship with him until his death. The two photographed together, and her work after 1965 is virtually indistinguishable from his.

The German photographers introduced new subjects—portraits, architecture, industry, dance—that were incorporated into the lexicon of Yishuv images. The themes supporting the JNF’s agenda remained constant: pioneers creating new settlements, farmers working the land, the armed forces, and immigrants arriving in their new country, all created with a sense of pride and new-born identity.

A watermelon photographed in the 1930s by Liselotte Grjebina (1908–1994, born in Germany, immigrated to Palestine in 1933) was evidently not produced solely for artistic pursuits, in spite of the avant garde composition and lighting. Stamped on the melon in clear Hebrew letters is an insignia with the words “Hebrew watermelon,” articulating the pride the early Zionists felt in the produce of the land they cultivated. A later work, Discus Thrower, shows a strong, beautiful female athlete poised before throwing the discus, shot from below; she is the female equivalent of the male pioneer, forming a “larger than life” heroic figure presenting an unmistakable argument countering antisemitic notions of weakness, physical or otherwise.

The Polish-born Hila Reichman (b. 1893), who studied in Vienna, ran a studio on her porch in Tel Aviv, where she photographed the leaders of the Yishuv. Aliza Holz (b. 1898) studied the new German style of photography with Alfred Bernhiem. She moved to Palestine around 1935 and similarly focused on portraits of celebrated figures in the Yishuv, including Martin Buber and Ben Gurion.

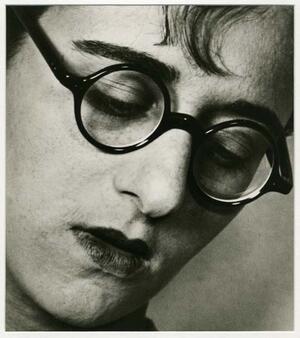

As the Yishuv matured and grew stronger, the photographs become bolder, both visually and in content. The figures came to the foreground, no longer anonymous additions to the landscape. Faces are close to the picture plane, defiant and stubborn.

Jewish Women Photographers After Independence

Following the founding of the State of Israel in 1948, immigrants and refugees from Europe streamed into the country, their obvious relief and joy coupled with the realities of adjustment and absorption. For the next decade, photojournalism became the prevalent mode of photography in Israel. Few women worked in this field, although in 1951 American photographer Ruth Orkin (1921–1985) traveled with the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, lived on a kibbutz for several months, and photographed Iraqi immigrants arriving at Lod Airport.

Photography in Israel during the 1950s and 1960s for the most part remained photojournalistic but was enhanced with a new sense of artistry. The late 1960s through 1970s were marked by the realities and consequences of the Six Day War (1967) and the Yom Kippur War (1973), the effects of which were extensively documented in photographs. By the late 1970s, the work of both natives and immigrants who studied in Europe and America, developing new ideas and influences, reflected a change in Israeli photography. International trends and a sophisticated understanding of the medium and its possibilities became very much a part of photography in Israel. The country’s economic and political maturity enabled the medium to develop as an independent art form and to be accepted as such. Though the photographers were freed of the need to create images for propaganda, their work was still informed by their individual connections to the country. Gone were the early days of Zionism and the deliberate, emotionally charged images. Innovative and creative photography blossomed, and the medium was essentially liberated from its ties to the past.

The Emergence of Photography as an Art Form in Israel

By the mid–1970s, photography’s significance in visual culture was recognized around the world. Museums began to form photography departments and collections, galleries opened, and auction houses offered sales devoted exclusively to photography. Though the medium was over 130 years old, it was newly perceived as an exciting and important mode of expression. The Israel Museum began exhibiting photographs in the early 1970s, and in 1977 both it and the Tel Aviv Museum opened their Photography Departments. Numerous schools created departments dedicated to photography, staffed by an influx of new teachers who had trained in other countries.

The new photography departments of the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, the Midrasha College of Art, Wizo Haifa, and Hadassah College generated many highly qualified, serious female photographers during the 1980s. Yet while photography in Israel flourished with the active support of museums, curators, collectors, schools, and galleries, the teachers, curators, collectors, and heads of photography departments were predominantly male. For example, there were no tenured women in the Bezalel Academy of Fine arts photography department before 2008 (Sadka, 2018).

Portraiture

Portraiture has been a traditional field for women photographers. Aliza Auerbach (b. 1940) began her photographic career in 1972 making movie stills, portraits, and photojournalist pictures. In 1991, she accompanied immigrants from Ethiopia and the former Soviet Union on their flights to Israel. She documented the realities of the process of leaving one’s homeland and family and becoming olim (new immigrants) in Israel. Aliyah, the Hebrew word for the act of moving to Israel, signifying “going up” to the holy land, is also the title of Auerbach’s 1992 book of photographs of the new olim. Neither idealized nor superficial, the photographs are sensitive and meaningful, enabling the viewer to understand the realities and complexities of the immigrants’ lives.

Vardi Kahana (b. 1959 in Tel Aviv) was asked by a friend suffering from cancer if she would document the remaining years of her life. Gili Pattir was diagnosed in the early 1990s, and soon afterwards she and Kahana began their collaboration. Pattir’s only stipulation was that the photographs be exhibited after her death. The result was Beauty Has Cut Itself Off, a group of remarkably powerful photographs that are direct and life-affirming in their sustained beauty. Kahana’s famous photograph of Emil Grunzwieg was taken moments before his assassination in a Peace Now demonstration in 1983 in Jerusalem. In 2007, Kahana presented “One Family,” a solo exhibit at the Tel Aviv Museum that documented her extended family in a wide scale project that presents the entire Jewish Israeli narrative through one family, a cross-section of Israeli society.

Before Ariela Shavid turned her camera on herself as a breast cancer victim, she had been a fashion model, artist, and mother. In Beauty is a Promise of Happiness, her 1996 exhibition at the Israel Museum, she examined femininity, sexuality, and ideal notions of beauty through posing and photographing herself in a variety of guises, all accentuating her post-mastectomy physique. In one series she is a single-breasted calendar pin-up girl, in another her face and body are projected onto cut-out paper dolls; both are evocative and question the idea and significance of beauty.

Kiki Elefant (b. 1956) also uses herself as the primary figure in her photographs. Technically not self-portraits, they attempt to solve a “multi-level identity dilemma … in relation to her past (the Holocaust) as well as present condition (gender).” In one 1997 work she holds a white strip in front of her eyes, creating a barrier between subject and viewer. She is apparently both shielding herself and preventing the viewer from seeing who she really is.

The portraits by Sharon Bareket (b. 1967) are unidealized and striking in their anachronism. Using teenage girls and women as models, she presents them wearing clothing and hairstyles popular many years ago in another, foreign country. The females project a sense of displacement, taken from one time and place and seemingly dropped into another (the land of Israel). Reminiscent of the many thousands of immigrants from the former Soviet Union living in Israel, the portraits are of people regularly confronted with the issue of “being Jewish” and therefore eligible for citizenship in Israel, according to the Law of Return.

Elinor Carucci (b. 1971) received her B.F.A. from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem before moving to New York in 1996. She received two major prizes: the 2001 ICP (International Center of Photography) Infinity Award for Young Photographer and the 2002 Guggenheim Fellowship. In addition to doing commercial work, she photographs herself and her family members in Jerusalem. While not altogether free of sexual tension, these intimate pictures convey the warmth and intimacy of her family life in Jerusalem and capture the essence of her relationships with those most important to her. Free of pretense, relationships rapidly tend to become warm and meaningful; Carucci’s pictures express this characteristic of Israeli life and culture. Clothed or nude, her subjects are as comfortable with themselves and the presence of the photographer as if the camera were invisible. The viewer becomes a voyeur, watching complicated familial relationships in situ as though through a two-way mirror (Eran Holds me in Hotel Room, 2000).

Noa Zait (b. 1967) photographs slices of life. They are not snapshots that record a decisive moment or capture a significant event but rather pictures of stories: street scenes, interiors, or urban landscapes—with people, but not necessarily about people. A seemingly homeless man crosses the street, his possessions in tow. Surrounded by signs telling him where not to turn, he nonchalantly walks ahead, against the red light. The idea of a bridge leading to an unknown destination combines with the undetermined fate of the homeless man to convey a sense of existential disinterest.

Socio-Political Photography

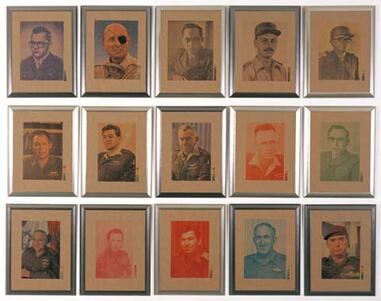

The Limbus Group was comprised of three women photographers, Judith Guetta (b. 1963), Galia Gur-Zeev (b. 1954), and Dafna Ichilov (b. 1964), who created photographic images together. They founded The Limbus Gallery in Tel Aviv, an important feature in the Israeli contemporary art world. Their seminal work, Embroideries of Generals, 1997, was recognized as an iconic work that undermines the myth of the Israeli war hero. They printed fifteen portraits of former Israeli army chiefs of staff onto a needlepoint canvas, thus undermining the notion of the macho male, as personified by the Israel war hero and leader, by using a material associated with women’s handiwork. It is a feminist statement unambiguously debunking the myth of the Israeli soldier, who has always been a symbol of masculinity and machismo.

Avishag Shaar Yeshuv is a photojournalist and commercial and fashion photographer who created poignant work of women in prison and female IDF combat soldiers. She has won the “Local Testimony” prize from the Israeli press exhibition.

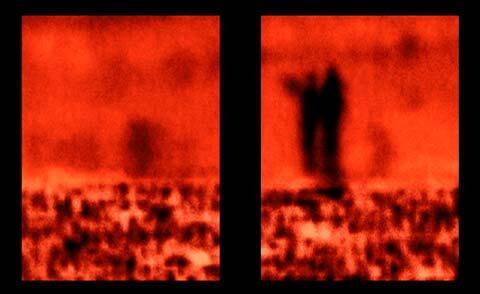

Michal Rovner (b. 1957) creates photographs, videos, paintings, and films that transcend both reality and abstraction. She studied at Tel Aviv University and then at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. In 1978 she co-founded the Camera Obscura Art School in Tel Aviv. Since 1988 she has lived in New York and spends much time in Israel, where she often shoots her material. She starts her photographs with images, from a Polaroid or video still, of staged or actual scenarios and then drastically reworks these images so that it is impossible to decipher what, where, or who is being represented. The results are powerful images that are blurry and almost featureless. In Decoy #12, 1991, Rovner photographed documentary footage from the television screen while the news showed images of deployed soldiers actively engaged during the Gulf War. She captured the running soldiers on film and repeatedly rephotographed them to enhance the color, scale, and texture until they were reduced to blurred outlines and fields of hazy color. Rovner, considered one of the most important photographers working today, had a mid-career survey exhibition of her work at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in Summer–Fall 2002, the first Israeli artist to be so honored. She represented Israel at the Venice Biennale, Summer 2003.

Using bomb shelters as stage sets, Tiranit Barzilay (b. 1967) typically presents a group of young women and men in states of dress and semi-undress standing in a carefully arranged group pose. Her characters are usually dressed in white, white and grey, or white and blue. White and blue, the national colors of the state of Israel, are traditionally worn by schoolchildren on Holocaust Day, Memorial Day, and Independence Day. The combination of this allusion to Israel, the subjects’ apparent emotional lack of interest in what they are doing, and their unresponsiveness to the camera in these tableaux vivants all evoke the sense of a soldier performing his duties. The mechanical gestures of the submissive young adults seem to portray the conflict between the collective and the individual that is inherent in Israeli society today. They are all together in the bomb shelter, yet engrossed and involved in their own separate activities.

Nurit Yarden’s (b.1959) projects shift between private and public space. This practice began with several exhibitions dealing with private space: Visual Diaries (2002), Home Cooking (2005), her artist book Family Meal (2007), and Family Files (2009), focusing on home and family, raising questions about sexual abuse and trauma. In 2010 Yarden started a visual diary based on wandering Tel Aviv, her home city. Her range has broadened from Tel Aviv to the entire country, reflecting her desire to become better acquainted with Israeli society its public spaces. Her project Sojourn is an independent ongoing residency project in Israel. Her work can be defined as a political-social diary, in which she attempts to point out aspects of society that people prefer not to see, such as issues of gender, power balances in Israeli society, and the occupation.

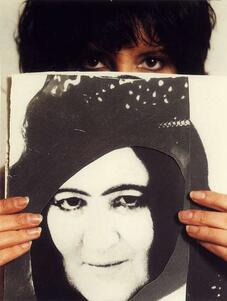

Michal Heiman (b. 1954) defines herself not as a photographer, but rather as a “photographic objector.” Experiencing photography and trauma as bound together led her to offer a new reading of the photographic medium. In her view, it is both a site imbued with libidinal exchange and a space of encounters, thus being an unethical tool. An artist, curator, theoretician, activist, founder of the Photographer Unknown archive (1984), and creator of the Michal Heiman Tests (M.H.T.s)1–4, Heiman teaches at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design and is a member of the Tel-Aviv Institute for Contemporary Psychoanalysis. She has contributed to the development of a discipline that joins history, visual culture, psychoanalysis, and human rights, focusing on women's rights. Her installations, enactments, archival materials, photographs, and film series are deeply rooted in the Israeli political, familial, and social arenas. Heiman was the first recipient of the Shpilman International Prize for excellence and research in photography, in collaboration with the Israel Museum. In recent years, she has focused on her on-going research with anonymous and marginalized women hospitalized in asylums and has had solo exhibits in Israel and the United States.

Landscapes

A dominant theme of photography since the 1970s is that of the “land” of Israel and the issues that accompany it. The earth, the soil, the very ground for which the people of the country continually battle and on which they farm and build structures takes on new significance. Preoccupation with the land, its geography, and territorial issues is seen in the work of Chava Salomon (b. 1914), Dalia Amotz (1938–1994), and Marli Shamir (b. 1919). They create imagery through a combination of direct knowledge of the history of the land and individual perspectives on its transformation and development.

Dalia Amotz was the first noteworthy female photographer to be born in Palestine, specifically on a kibbutz. She consistently photographed the Israeli landscape and the effect of natural light on its transformation. Amotz’s connection to the physical “land” of Israel is both visually and metaphorically powerful, particularly in her photographs of Arab villages.

In her large-format color photographs Ruth Agassi (b. 1949) conveys a strong sense of time and place without actually disclosing where the subject is located. The viewer is drawn into the scene by its pure beauty and familiarity, then distanced by its anonymity. Agassi has also done photographic series of domestic interiors that are devoid of specifics about place but succeed in capturing strong feelings of rootedness.

Shirley Wegner creates large-scale photographs of landscapes informed by nostalgia and ideology. Her landscapes question the relationship between documentary photography, storytelling, and the way in which her own memories were shaped by early imagery of her homeland of Israel.

Photojournalism and commercial photographers

Photojournalist Efrat Shvili (b. 1955) works in the Jerusalem bureau of the Los Angeles Times. She studied photography at the Meimad Art School in Tel Aviv (1989–1990) and the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design (1991–1992) and received an M.A. in political science at Oxford University, England (1978–1981). For artistic reasons her photographs are untitled, although when used for documentary purposes they are designated eponymously. They depict towns and neighborhoods, including Ramot and Pisgat Ze’ev—land lost by Jordan to Israel during the Six Day War. These lands, considered by some to be disputed territory, are referred to as the “Occupied Territories” or as “Greater Jerusalem,” depending on the speaker’s position on the political spectrum. The photographs are clear political statements: the houses shown appear to be half-built and devoid of life; they are not integral to the surrounding landscape; they are presented as uniform pre-fabrications; yet they are still standing. Disclosing no unique characteristics, the houses and towns are interchangeable. Shvili was featured in three major international exhibitions in 2003: Venice Bienniale, Istanbul Biennial, and the International Center of Photography’s Triennial.

Judy Orgel Lester (b. 1944) carries the double distinction of having achieved successful careers in both commercial and artistic photography. She studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York in the late 1960s with her husband, photographer Kenny Lester, at the same time as Gary Winogrand, Robert Frank and Bruce Davidson. After returning to Israel in 1970, the couple opened the Judy and Kenny Studio, a commercial photography establishment. Judy was instrumental in founding of The White Gallery, the first photography gallery in Tel Aviv, and exhibited her work there beginning in 1979.

Michal Chelbin (b. 1974) creates poignant portraits of unusual people on the fringe of society: wrestlers, dwarfs, acrobats, migrants, and circus workers. Other portraits are of rapists, cannibals, and murderers in the Ukraine and Russian prisons. She also defines herself as an artist who creates fashion photography. Working with Dior and Gucci designers, she contributes work regularly to the New York Times magazine, the New Yorker, the Guardian, the Sunday Times, Le Monde, the Financial Times, and others.

Conceptual Photography

Deganit Berest (b. 1949) created her Dreams series by layering images (both visually and metaphorically), resulting in provocative photomontages difficult to decipher. The ephemeral qualities of these large-format color photographs force the viewer to explore the possibilities of interpretation. A painter as well as a photographer, Berest has had many solo exhibitions around the world and is an important teacher in Israel. She graduated from the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design in Jerusalem in 1973 and received her M.F.A. from Pratt University in New York in 1980. She was awarded many prestigious prizes over the years from the Tel Aviv Museum, Tel Aviv municipality, Minister of Education, and the Israel Museum.

Whether photographing the insular world of Me’ah She’arim, body parts floating in water, or still lives of dead animals, Pesi Girsch (b. 1954 in Munich, moved to Israel in 1968) consistently emphasizes formal composition. Flawless both technically and compositionally, her images reveal a quiet and peaceful beauty. She studied sculpture with Rudi Lehmann (1903–1977) from 1969 to 1974, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich in 1977, and at the Art Teachers’ College in Ramat ha-Sharon in 1987. Untitled, in which body parts from several human beings can be discerned, is a clear reference to Girsch’s experience as a second-generation Holocaust survivor. Her work has been widely exhibited and she has received many prizes. She teaches in the Art Department of Haifa University.

In her photographs, Orit Raff (b. 1970) closely scrutinizes man-made objects, ranging from a close-up of a row of buttons on the front of a white shirt to ice formed in a freezer; the resulting images are elegantly minimal yet visually rich. Her works are quiet, intelligent studies of what appear to be abstractions but which, under close examination, are revealed to be everyday white things simply transformed by the photographer and her camera into conceptual images. Though she focuses on the abstraction of objects, allegorically, her photographs can be interpreted as representing the fragility of Israel’s borders. Raff expresses the body and domestic space we inhabit as symbolic of the land of Israel.

Leora Laor's (b. 1952) pictures are about people and their psychological states. Observed from afar, the subjects range from playful children to alienated adults. All are infused with an unusual combined sense of pictorial wonder, romanticism, and emotional isolation.

Jewish Women Photographers in the Twenty-First Century

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, Israel continues to be consumed with conflicts relating to national, religious, political, and cultural identity, as well as threats to the country’s very survival. Many photographers have a social conscience that, while in keeping with liberal opinion elsewhere, has an element specific to Israel’s political complexities and almost daily moral dilemmas. The majority of Israeli women photographers explore their own personal realities—including nationality, identity, and a preoccupation with time, place, and self—in addition to social and political issues and the lives and experiences of others.

The twenty-first century has witnessed a remarkable increase in creative activity by Israeli women photographers, many of whom have won recognition abroad. The role and status of women in society and forms of female presentation and representation have become rich subject matters. Rona Yefman (b. 1972), for example, explores gender, identity, and the tension between illusion and reality. She intentionally erases gender differences in her photos, searching for new definitions of gender identity. Yael Meiry (b. 1982) examines transgender, queer identity through photography dealing directly with subjects considered taboo.

Sigal Avni (b. 1960) photographs distorted bodies and spines, presenting women devoid of sexuality. Tamar Masel's (b. 1965) photographs deal with the masculine gaze: photographing portraits from behind, revealing the neck and hair, restraining sexuality, and avoiding direct feminine attributes, such as beauty. Chen Cohen, who was awarded the Gerard Levi prize by the Israel Museum in 2021, works with mixed media, exploring the fragile body as an arena of struggle, pain, and abuse. Lea Golda Holterman (b. 1976) deals with issue of religion, gender, and identity and exposes visual aspects of sexuality among Orthodox Jewish men.

Vered Nissim (b. 1980) examines questions of identity, social status, and gender in the environment of her home, family, and private life, using media, photography, sculpture, installation, video, and video performances. She created powerful images of her parents in a series dealing with the social status of the Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi population in Israel. Noa Ben-Shalom (b. 1975) turns her camera to look at how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has permeated all aspects of life in Israel. Efrat Shalem (b. 1972) deals with culture, locality, history, and identity.

For her project “No Thing Dies” at the Israel Museum, Ilit Azoulay (b. 1972) interviewed curators, archivists, and conservators, studied the museum’s archives, and surfaced artifacts that had never been publicly exhibited. These items were displayed in large collages in 2017, alongside stories about their original purpose, their journeys to the museum, and the challenges of their preservation. In 2008, she exhibited Finally Without End at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, including photographs of scraps and remains of daily life composed during her six-month residency in Berlin.

Naomi Leshem (b. 1963) photographs landscapes and is interested in the concept of time. She created a series of images of sleepers: attractive young people in bed, asleep, depicting stages of transitions from childhood to adulthood, wakefulness to sleep. Other active photographers are Hadas Satt (b. 1981), who focuses on public gardens and wildlife parks; Noa Ben-Nun Melamed (b. 1954); France Lebee Nadav (b. 1956); and Orit Siman-Tov (b. 1971).

Ronit Shani (b. 1950) is considered one of the most prominent Israeli photographers today; she photographs her surroundings with a sensitive eye. After studying photography in London and completing a Masters at the Pratt Institute in New York, Shani returned to Israel in 1977 and taught in the Midrasha College, Camera Obscura, Koteret School, Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, and Tel Aviv University, influencing generations of Israeli photographers. She exhibited extensively, published books on Israeli photography collections, and was awarded the prize of the Israel Museum and the Israeli Minister of Culture.

Tal Shochat (b. 1974) photographs fruit trees against cloth backdrops. Her work is meticulous and theatrical, created with precision and rich vibrant colors. Her photographs deal with natural and artificial life, the real and the imaginary, the personal and the collective. The Indie Gallery in Tel Aviv promotes photography; among its artists are Lihi Binyamin (b. 1986), Ronit Porat (b. 1975), and Keren Zaltz (b. 1981). Dana Lev Livnat (b. 1978) embarked on her “Permanent Vacation” photography project in 2013, leaving Israel to travel the world. The project is based on one rule: she must post images on social media every two hours, and every image must document one moment of her last 24 hours. Etty Schwartz (b. 1970) photographs nature using Instagram.

Others active photographers include Osnat Bar-Or, Sheffy Bleier, and Ayelet Hashachar-Cohen, who creates intimate hand-tinted and hand-painted images and heads the photography department at the Musrara school of Art and Society. Shai Ginott, a self-educated photographer, specializes in scenes from nature from an environmental standpoint. Vivienne Silver-Brody, a historian of photography in Israel, is author of Documentors of the Dream: Pioneer Jewish Photographers in the Land of Israel 1890–1933 (1998) and From Mirror to Memory—One Hundred Years of Photography in the Land of Israel (2000). Until her untimely death in 2001, Shosh Kormosh was a highly creative and unique force in the field of photography in Israel, specializing in portraits and a super-realistic style.

Photography Research

Although as of 2021 there have been no female photography professors in Israel, Israeli women trained at the PhD level in photography participated in and shaped critical public discourse through research in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Diverging from the mainstream, they construct alternative historical narratives and legacies. Their narratives include a discourse critical of Zionist history, visual legacies of the Nakba, and militarism, as well as deconstruction of gender hegemonies and hierarchies in Israeli society.

Ariella Azoulay is an internationally renowned scholar, art curator, filmmaker, and theorist of photography and visual culture. She is a professor of Modern Culture and Media and the Department of Comparative Literature at Brown University. She researches archives dealing with photographic presentations of oppression resulting from colonialism, imperialism, and militarism.

Rona Sela is a curator, visual history and culture researcher, and lecturer at the Tel Aviv University. Since 1996, she has researched the history of colonial Zionist and Israeli photography and archives; women photographers in Palestine/Israel 1920-1970; photography and marginal populations in Palestine; Palestinian photography; the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; cultural looting and seizure; archives under occupation; Nakba images; Palestinian visual history in Israeli archives; and visual representations of conflict, war, occupation, exile, immigration, and human rights violations. Sela raises questions about the role of archives, archivists, and researchers in colonial regions and zones of conflict. She explores the process of Israeli colonial archives becoming a large reservoir of Palestinian knowledge and information and exposes the means by which Jewish and Israeli forces (institutional bodies, soldiers, citizens) control Palestinian knowledge and manipulate the writing of history. After seizing and looting Palestinian archives and artifacts, Israel controls them in Israeli archives through censorship, restricted access, and biased interpretation.

Hagit Keisar has also researched and created visual archives, uncovering stories of Palestinian villages, personal histories, and various aspects of migration and deportation, civic inequalities, and human rights violations. She has conducted critical research on aerial photographs in Israel/Palestine and carried her own work using do-it-yourself aerial photography techniques.

Ruthie Ginsburg is a visual culture researcher who deals with human rights and photographic presentation of oppression. Focusing on photographs women combat soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), Chava Brownfield-Stein examines visual representations of women combatants in popular news and social media. She works with images of female cultural militarism in terms of “erotic militarization.” Edna Barromi-Perlman is a visual researcher who explores the influence of Zionist ideology on the construction of personal photo albums and personal visual histographies of kibbutzim during the Yishuv. She researches online and historical photo archives and their role in creating Zionist myths. Vered Maimon is a photography theorist at Tel Aviv University who contributed to arranging international photography conferences in Israel, bringing Israel to the academic forefront in photographic theory. Ruth Oren curated historical photographic exhibits in the Eretz Israel Museum and researched the history of photography in Israel. Ya'Ara Gil Glazer combines discourses in photography and education through the lens of critical pedagogy, which she used to research Arab and Jewish college students' shared histories of migration.

Ayelet Kohn analyzes Instagram photos posted on the official website of the IDF, examining Israeli Instagram users’ presuppositions and emotional attitudes about the ideologies and values of the IDF. Her research in visual communication deals with objects that serve as props in political speeches and the use of such objects as rhetorical arguments in three speeches by Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

After years of male domination, the field of photography in Israel is shifting. Recent exposure of severe cases of sexual abuse and misconduct by senior male staff in various photography departments in Israel has also jolted the existing patriarchal structure. Women’s activity, determination, and quality of work in this field have generated a change in Israeli society. The past and present contribution of women in shaping photographic discourse is now more appreciated, and their value and worth in developing photography in Israel is acknowledged.

Acknowledgments: Edna Barromi-Perlman would like to thank her former student, Noa Sadka, for her assistance and contribution in compiling a list of active photographers in Israel in 2021.

Auerbach, Aliza. Aliya. Tel Aviv: Ministry of Defense Pub. House, 1992.

Barromi-Perlman, Edna. “Practices of photography on kibbutz: The case of Eliezer Sklarz.” Journal of Israeli History: Politics, Society, Culture. Vol. 34. No. 2 (2015): 181-203.

Gidal, Tim N. “S. Narinsky of Palestine.” History of Photography (April 1981): 125–128.

Goldfine, Gil. “Mechanical Images and the Painted Surface.” The Jerusalem Post, July 1, 2001.

Goldfine, Gil. “Lens sana in corpore dubio.” The Jerusalem Post, December 14, 2001.

Hannavy, John. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. London: Routledge, 2008.

Goodman, Helen. “Photographers.” Encyclopedia of Jewish Women in America, edited by Paula E. Hyman and Deborah Dash Moore, 1060-1066. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Goodman, Susan Tumarkin. After Rabin: New Art From Israel. New York: Jewish Mueum, 1998.

Graham-Brown, Sarah. Images of Women: The Portrayal of Women in Photography of the Middle East 1860-1950. New York: Quartet, 1988.

Honnef, Klaus, and Frank Weyers. Und Sie Haben Deutschland Verlassen … Mussen. Fotografen und ihre Bilder 1928–1997. Bonn: PROAG, 1997.

Levine, Angela. “Points of Departure.” The Jerusalem Post, January 29, 1993, 21.

Maor, Hadas. Ruth Agassi: Detailed Horizon. Tel Aviv and London: 2001.

Nessel, Jen. “Ghostly Visions.” ARTnews (Summer 2000): 138–140.

Newhall, Beaumont. The History of Photography from 1839 to the Present Day. New York: Museum of Modern New York, 1964.

Oren, Ruth. “Zionist Photography, 1910–1941: Constructing a Landscape.” History of Photography 19/3 (1985).

Perez, Nissan N. Time Frame: A Century of Photography in the Land of Israel. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 2000.

Perez, Nissan N. “Photography in Israel: A Late Awakening.” In Here and Now: Israeli Art. Jerusalem: 1982.

Perez, Nissan N. and Lea Dovev. Beauty is a Promise of Happiness: Ariela Shavid. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1996.

Perez, Nissan N. Condition Report: Photography in Israel Today. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1998 (CD-ROM).

Rosenblum, Naomi. A History of Women Photographers. New York: Abbeville Press, 2000.

Shapira, Sarit. “Some Notes on the History and Context of Young Israeli Art.” In Contemporary Art From Israel at the First International Art Biennial, Buenos Aires. Tel Aviv: 2000.

Raz, Guy. Photographers of Palestine, Eretz Israel/Israel (1855-2000). Tel Aviv: 2003.

Sadka, Noa. Photographic Truth is Natural Truth-Chronicles of a Photography Department. Tel Aviv: Resling, 2018.

Sela, Rona. "Women Photographers in the Private Arena, Women Photographers in the Public Arena." In Women Artists in Israel, 1920-1970, edited by Ruth Markus, 99-138. Tel Aviv: Ha-Ḳibuts Ha- Meʼuḥad, 2008.

Sela, Rona. "In the Footsteps of Forgotten Women Photographers, The Era of Zionist Photography, from the 1930s to the 1960s." Studio Art Magazine 113 (2000): 34-44.

Silver-Brody, Vivienne. Documentors of the Dream: Pioneer Jewish Photographers in the Land of Israel 1890-1933. Jerusalem and Philadelphia: Magnes Press and Jewish Publication Society, 1998.

Silver-Brody, Vivienne. From Mirror to Memory: One Hundred Years of Photography in the Land of Israel. Haifa: Mané-Katz Museum, 2000.

Vine, Richard. “Report From Israel: Wider Focus.” Art in America. May: 2000.