Vered Nissim

Multi-disciplinary artist, curator, and art consultant Vered Nissim was born in Israel to Iraqi immigrant parents. She identifies as a Mizrahi feminist; her art revolves around her gender, ethnic, and class identities, and she aims to give voice to marginalized women in Israeli society. Nissim seeks to provide an alternative to the rigid canon determined by mainstream art by presenting works that undermine Israel-Western aesthetic values and content. She uses materials and art forms that the mainstream art world regards as “improper.” Like other feminist Mizrahi artists, she uses her artwork to articulate the obstacles they face in their daily lives, including inequalities and oppression in the job market, racial profiling, sexual exploitation, and the degrading attitude toward Mizrahi culture in general and feminine Mizrahi culture in particular.

Family and Identity

Multi-disciplinary artist, curator, and art consultant Vered Nissim was born in the city of Holon, Israel, on August 4, 1980. She was brought up in a working-class family of newcomers who arrived in Israel in 1954 from Baghdad, Iraq. Her family included her father, Benjamin, her mother Esther (Suada), and her siblings Liat, Lior, and Ronen, who passed away young. She has been especially influenced by her mother, a cleaning and maintenance person by profession, and has even included her mother in most of her art projects.

Nissim earned a B.F.A from the Midrasha School of the Arts, Beit Berl College (2006) and an M.F.A from the arts department, Haifa University (2017).

Nissim self-identifies as a Mizrahi feminist, and her art revolves around her gender, ethnic, and class identities. She holds a political Lit. "Eastern." Jew from Arab or Muslim country.Mizrahi worldview, aiming to give voice to marginalized women in Israeli society. She seeks to provide an alternative to the rigid canon determined by the mainstream art field by presenting works that undermine Israeli-Western aesthetic values and content. One of the ways in which she does this is by utilizing materials and art forms that the hegemonic art world regards as “improper”—folkloristic and decorative art customarily deemed unworthy of inclusion in the discourse of visual culture.

A Sun Composed of Cleaning Gloves

One such piece is an installation (Untitled, 2014) set on the floor, whose composition consists of dozens of simple, cheap, yellow rubber cleaning gloves arranged in the shape of a circular shining sun.

The artist explains that the sun—a symbol of bright light—here ironically creates questions regarding color and shades of darkness. Nissim’s dark-skinned Iraqi heritage seems to be pleading with the sun, as if whitening her dark looks in order to whitewash her black skin clean, its warm beams casting out all the shadows of her Mizrahiness. The use of yellow gloves to symbolize the sun evokes a matrix of associations. One such associations is the stereotype of the “hot-as-sun” Mizrahi woman—an inhabitant of the Orient, which, as Edward Said asserts, still suggests not only fecundity but also sexual promise (and threat), untiring sensuality, and unlimited desire. Another is that of the sunflower, whose seeds are, in the dominant public imagination, consumed by oriental women lounging on sun-flooded Middle Eastern balconies—an image sharply contrasting with Van Gogh’s Western, civilized iconic sunflower. Likewise, it evokes, states Nissim, the stereotypes of kitsch and bad taste, Mizrahi woman regularly being called freha or slutty. Nissim thus employs a style, content, and medium that subverts the good taste of high art, disrupting the proper social order.

In this piece, Nissim also uses a strategy of humor as subversion. The work addresses repressed histories and the fragile nature of contemporary assumptions about marginalized subjects, such as Mizrahi women. The cheap yellow gloves evoke the stereotype of the under-educated Mizrahi woman who stays at home to cook, clean, and take care of her large brood rather than the standard, Western 2.4 children that enable women to earn a higher education and develop a career outside the home. Because they are of lower socio-economic status, Mizrahi women in Israel are frequently associated with cleaning and maintenance jobs, not only in offices and factories but also for rich Ashkenazi families. Nissim confronts the viewers with the ever-growing gap between ethnic groups as Mizrahi women choose or are compelled to work in low-paid, low-status jobs. She also accentuates the limited opportunities open to Mizrahi women for higher education and their confinement to the periphery—whether geographic, economic, or cultural. Women living in peripheral areas generally do not receive sufficient and high-quality education; often their social mobility is restricted, perpetuating their low-income status. Finally, the artist states that the plain, cheap yellow gloves bear a very personal meaning for her, as they are an integral part of the daily equipment of her mother, who works as a cleaning woman.

The use of the yellow rubber cleaning gloves (made to protect laboring hands from toxic cleaning products and overuse) to symbolize the sun also raises the question of the tension between function and aesthetics. Nissim prompts the viewer to consider whether Mizrahi women can ever be totally clean(s)ed of their blackness—or whether they are forever doomed to suffer the consequences of the dominant society’s power relations and remain economically and culturally suppressed. Calling attention to multiple ongoing power relationships—between Mizrahis and Ashkenazis, blacks and whites, impoverished and affluent, men and women, Nissim lays bare the complex, multilayered, intersectional positions of various members of Israeli society. The contrast between domestic (feminine) cleaning and the creation of high art in the (masculine) public space of the museum places identity construction—including racialization and gendering— at center stage.

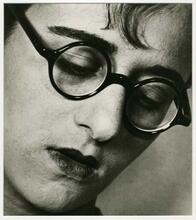

Self-Portrait: Half Free

Nissim’s 2005 self-portrait photograph “Half Free” allows her to embark on a multi-layered discussion of gender, race, and class dimensions. The title refers to an Israeli supermarket chain that offers low-priced basic food items in outlets on the outskirts of big cities. Targeting low-income families, it is famous for its cheap plastic shopping bags.

In this image, the bag with its writing, Half Free, covers Nissim’s face, leaving her choking for air. Both shocking and grotesque, the image exemplifies how humor can subvert fossilized cultural values. A unique type of weapon, humor takes freedoms with conventional moral, social, and economic values.

Placing the issue of class at the center of this work, Nissim states that it gives visibility to people who are invisible—namely, blue-collar workers. This piece not only refers to the socio-economically lower class but also reflects the traditional gender division of labor, as women are expected to be in charge of shopping for groceries and cooking for the entire family. The woman in this photograph, with her dark skin and bright red lipstick—an allusion to the “sluttiness” traditionally attributed to Mizrahi women—signals the threefold oppression from which Mizrahi women suffer: class, gender, and ethnicity. In so doing, Nissim seeks to undermine stereotypical attitudes and to highlight the political intersections of various categories of identity categories.

Civic Guard

In a 2006 photo titled “Civic Guard,” Nissim again chose to present herself, this time dressed in a uniform of a contracting company providing security services to major shopping centers, her dark-skinned face fitting the exploitative occupational profile of Mizrahi women in contemporary Israel.

This choice draws subversive attention to the status of Mizrahi women in Israeli society, many condemned to work in temporary, exploitative jobs to ensure the safety of the general population while having no financial security of their own. Nissim takes an ironic and humorous approach: in the contemporary era of surveillance and security cameras, secret undercover government activities, and unstable security around the globe and in the Middle East in particular, a woman with no proper training is put in charge of the safety of hundreds of thousands of people visiting shopping malls. Not only are security checkpoints common in Israel, but profiling forms one of the central tools for foiling potential threats. Here, the Mizrahi worker is employed to prevent the danger she herself is often seen as constituting: the Arab/Other/enemy. In charge of securing the area, she symbolizes the dominant order as it prevents women such as herself from penetrating the public sphere and taking equal part in the civic, cultural, and economic life of the country. Nissim also emphasizes the doubly oppressed position of the woman in the image: in contrast to the prestigious security jobs (for men fighting in the IDF and protecting the home front with real weapons), she is left with the much less prestigious, un-skilled, civilian job of checking bags at the entrance to a shopping mall.

“Civic Guard” also represents the marginality from which Mizrahi women suffer under Israeli neo-liberalism, drawing attention to the fact that security guards employed by contracting firms are exploited financially and have no job security. Workers in unskilled jobs—cashiers, cleaners, care-givers, security guards—are extremely vulnerable to abuse. Contracting firms in Israel in particular exploit the system and trend towards privatization in order to gain greater a share of the non-professional market sector at the expense of those least able to stand up for their rights, including working conditions, over-time wages, sexual harassment, social and employment security, and more.

“Civil Guard” also reveals the ethnicization and gender processes prevalent in Israel—Ashkenazim work in high-salary, high-status, high-tech jobs, Mizrahim in low-paid, low-status, “low-tech” jobs, and 70% of minimum wage jobs in Israel are filled by women. The majority of women in Israel who work in low-paid jobs are resigned to being exploited, frequently not even expecting to gain a fair recompense for their labor.

Feminist Mizrahi women artists such as Nissim thus use their artwork to articulate the obstacles they face in their daily lives. Such obstacles include inequalities and oppression in the employment market, racial profiling, sexual exploitation, and the degrading attitude toward Mizrahi culture in general and feminine Mizrahi culture in particular. These artistic representations draw attention to and help to undermine patriarchal-Ashkenazi-neoliberal hegemony.

Self-Portrait: Untitled

Nissim not only reveals the oppressive facets of being a Mizrahi woman but also accentuates and celebrates her Mizrahiness, creating positive and powerful representations of Mizrahi women. In Untitled, a photograph from 2011 (Figure 4), the woman—Nissim herself—sits naked on her kitchen counter, her body covered in cooking oil and Kuba dumplings, a traditional Iraqi food.

While this scene may be understood as Nissim’s homage to her mother—an important figure in the artist’s life who dedicated herself to taking care of her family and cooking their favorite foods—it also reveals a fiercely critical stance against ethnic and gendered stereotypes. Often, the kitchen is presented as the only Mizrahi cultural arena, as if eating is the only activity in Mizrahi culture. Nissim explained that this piece was meant to subvert the derogatory representation of the Mizrahi woman chained to her kitchen and replace it with a young, beautiful, assertive woman who chooses to continue the matrilineal Mizrahi tradition, from a new stance, proud of who she is.

Conclusion

Mizrahi artists such as Nissim create a self-reflexive gaze as part of their effort to construct a valid, sovereign identity. They hope to liberate their stereotypical image from being perpetuated as the Other in terms of ethnicity, and instead call to celebrate Mizrahi culture, and Mizrahi women especially.

Nissim has won eight prizes, among them the Oded Messer Prize for a Young Artist (2008); the Pais Prize for Artists (2008); the Joshua Rabinovich Prize (2011); the Young Artist Prize of the Israeli Ministry of Culture (2015); and the Becki Dekel Prize for Leading Feminist Israeli Artist (2020). She has had six solo exhibitions and taken part in over 30 group exhibitions.

Alon, Ktsia. “Mizrahi Women's Voices in Israeli Art – A Cross Section.” In Ktsia Alon and Shula Keshet, eds., Breaking Walls: Contemporary Mizrahi Feminist Artists, edited by Ktsia Alon and Shula Keshet, 278-244. Tel Aviv: Achoti Press, 2013.

Calderon, Nissim. Pluralists Despite Themselves. Haifa: University of Haifa Press, 2000. (Hebrew)

Chinski, Sara. “The Silance of the Fish: The Local versus the Universal in the Israeli Discourse on Art.” Theory and Criticism 4 (1993): 105-122. (Hebrew)

Dahan-Kalev, Henriette. “Tensions in Israeli Feminism: The Mizrahi Ashkenazi Rift.” Women's Studies International Forum, 24, no. 6 (2001): 1-27.

Dekel, Tal. “From First-Wave to Third-Wave Feminist Art in Israel: A Quantum Leap.” Israel Studies Journal 16, no. 1 (2011): 149-178.

Dekel, Tal. Gendered—Art and Feminist Theory. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013.

Keshet, Shula and Rita Mendes-Flohr, curators. For my Sister—Mizrahi Artists in Israel. Jerusalem: Antea Gallery, 2000. (Hebrew)

Levy, Gal. “A Lost Decade, or, Where Has the Mizrahi Narrative Gone Since the 1990s?” The Open University, Israel (2008). www.openu.ac.il/Personal_sites/gal-levy/A_Lost_Decade.pdf

Markovich, Dalia and Ktzia Alon. “Portraits from the Margins of the Employment World.” Haaretz, December 13, 2006, 17. (Hebrew)

Misgav, Chen. “Mizrahiness.” Mafteh, 8 (2014): 67-92. (Hebrew)

Motzafi-Haller, Pnina. “Knowledge, Identity, Power: Mizrahi Women in Israel.” In To My Sister: Mizrahi Feminist Politics, edited by Shlomit Lir, 87-113. Tel Aviv: Bavel, 2007. (Hebrew)

Nissim, Sarit and Orly Benjamin. “The Speech of Services Procurement: The Negotiated Order of Commodification and Dehumanization of Cleaning Employees.” Human Organization, 69, no. 3 (2010): 221-32.

Shenhav, Yehuda, ed. Coloniality and the Postcolonial Condition. Tel Aviv/Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute/Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 2004. (Hebrew)

Shiran, Vicki. “Deciphering Power: Creating a New World.” In To My Sister: Mizrahi Feminist Politics, edited by Shlomit Lir, 34-35. Tel Aviv: Bavel, 2007. (Hebrew)