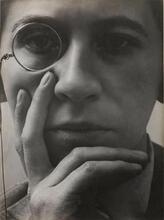

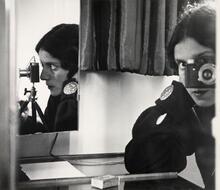

Trude Fleischmann

Trude Fleischmann opened her studio at age 25, worked as a successful independent photographer through the Depression, and photographed some of the great artists, thinkers, and activists of her day, including Max Reinhardt, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Albert Einstein. In 1920 she founded her studio, photographing musicians and performers for magazines. Her expressive, often erotic style brought her difficulties in 1925 when her powerful nude photographs were confiscated for indecency. Fleischmann fled the Anschluss in 1938, first to Paris and then New York, where she opened a studio in 1940 with fellow émigré Frank Elmer. Her clients included many artists and intellectuals who had fled Europe, as well as noted Americans. In 1969 Fleischmann retired to Switzerland, and in 1987, she returned to the US.

Trude Fleischmann, who developed a passion for photography already as a child, rapidly became one of Vienna’s leading portrait photographers soon after opening her own studio at the age of twenty-five. Though she is largely unrecognized today, her outstanding portraits of intellectuals and artists, including Karl Kraus (1874–1936), Peter Altenberg (1859–1919), Adolf Loos (1870–1933), Alfred Polgar (1873–1955), Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), Alban Berg (1885–1935), Bruno Walter (1876–1962), Max Reinhardt (1873–1943), Paula Wessely (1907–2000) and Grete Wiesenthal (1885–1970), remain an important record of twentieth-century European culture. That she was able to continue her successful career after emigrating to the United States attests to her flexibility and talent in a field to which she later referred as the most important aspect of her life.

Early Life and Family

Born in Vienna on December 22, 1895 as the second of three children in a wealthy Jewish family, Trude Fleischmann attended the Lyceum of the School Association for the Daughters of Civil Servants. Her family, including her father Wilhelm, a salesman originally from Hungary, and mother Adele (neé Rosenberg) constituted a major source of financial and emotional support in her early career. Her training included one semester studying art history in Paris and three years at the “Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt für Photographie und Reproduktionsverfahren,” where women had been allowed to train in photography only since 1908. Upon finishing her studies in July, 1916 she became an apprentice photo-finisher in the studio of the well-known portraitist Madame D’ora (Dora Kallmus), whose work she greatly admired. Because d’Ora complained about her slow pace, she left after only two weeks. Shortly thereafter, Fleischmann managed to secure a position with photographer Hermann Schieberth, whose clients from the Viennese cultural and intellectual scene greatly interested her. In 1919 she became a member of the Viennese Photographic Society. After three years, with the encouragement of her mother and financial backing of her family, she founded her own studio in 1920. Fleischmann, who never married, had a number of relationships with women.

Photography Career

That Fleischmann was able to pursue a successful career during the economically unsound interwar years speaks to her talent, especially since she did not photograph weddings or baptisms, nor did she remain under contract with any magazines. The boom in photography during the interwar years, which paralleled the growth of magazines, also aided her career. Fleischmann’s artistic portraits of opera, music, dance and theater celebrities soon became indispensable to the Austrian and international print media, including Die Bühne, Moderne Welt, Welt und Mode and Uhu. As her circle of friends in the art world grew, Fleischmann’s studio became a gathering place for Vienna’s cultural elite. Her lack of fixed assignments and clients allowed her more freedom in subject matter and style, as can be seen from the expressive and often erotic manner in which she portrayed the faces and bodies of her subjects. Fleischmann was among the first to photograph the new dance styles in Vienna and in 1925 an exhibit of her photographs featuring dancer Claire Bauroff was confiscated by a Berlin district attorney for indecency.

Fleischmann’s career in Vienna represented part of a trend in which a number of women, many of them Jewish, pursued careers in photography, which, as a relatively new commercial media, was comparatively easy to enter. Like some others, Fleischmann regarded photography as a craft rather than an art, an attitude which also helped open the field to women.

Because of her Jewish background Fleischmann was forced to seek work elsewhere after the Auschluss in 1938. Leaving behind most of her negatives, she emigrated to Paris, London and eventually, with the help of her former student and lover Helen Post (1907–1979), to New York. There Fleischmann pursued a successful career in photography, first together with Post and, after 1940, in her own studio at 127 West 56th Street, which she ran until 1969 together with Frank Elmer, another Viennese émigré. Unlike her earlier work, many of these later photographs feature the New York cityscape, as well as fashion models whom she often photographed for Vogue. Her clients in New York also included emigrants from the European cultural scene such as Elisabeth Berger, Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980), Lotte Lehmann (1888–1976), Otto von Habsburg (b. 1912), Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894–1972) and Arturo Toscanini (1867–1957). In 1969 Fleischmann retired to Lugano, Switzerland, claiming she did not want to return to Vienna because of the behaviour of the population during the war. In 1987 she returned to the United States to live with her nephew, pianist Stefan Carell, in Brewster, New York until her death in 1990.

Auer, Anna and Carl Aigner. Trude Fleischmann. Fotografien 1918–1938. Vienna, 1988.

Auer, Anna and Kunsthalle Wien, eds. Übersee. Flucht und Emigration österreichischer Fotografen 1920–1940. Vienna: 1997.

Herrberg, Heike, and Weidi Wagner. Wiener Melange: Frauen Zwischen Salon und Kaffeehaus. Berlin: 2002.

Schreiber, Hans. Trude Fleischmann. Fotografin in Wien 1918–1938. Vienna: 1990.