Kashariyot (Couriers) in the Jewish Resistance During the Holocaust

Isolated from the outside world, Jews in Nazi-created ghettos relied on kashariyot (couriers) to bring news, goods, and sometimes other Jews to the ghettos. Originally created to sustain schools, soup kitchens, and culture within ghettos, these young women were already part of Jewish youth groups and were able to blend in with the Polish population. After learning of the Nazi mass extermination plan, their work shifted to acquiring weapons and rescuing Jews, all while evading capture from several groups; none of the kashariyot expected to survive. While the people who fought the Germans within the ghettos are often most celebrated for their bravery and heroism, the kashariyot were essential in the survival of Jews within ghettos.

Introduction

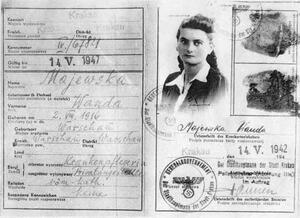

The Courierkashariyot were young women who traveled on illegal missions for the Jewish resistance in German-occupied Eastern Europe during the Holocaust. Using false papers to conceal their Jewish identities, they smuggled secret documents, weapons, underground newspapers, money, medical supplies, news of German activities, forged identity cards, ammunition—and other Jews—in and out of the ghettos of Poland, Lithuania, and parts of Russia. Their name comes from the Hebrew word for connection, kesher, because the kashariyot provided the kesher for Jews who were trapped in ghettos. The kashariyot were a lifeline—a “human radio” for news and information, a trusted contact for supplies and resources, and a personal inspiration for hope and resilience.

During the Holocaust the kashariyot were seen as fearless heroes whose death-defying activities were a source of great pride. Emmanuel Ringelblum, the distinguished historian who organized the underground archive in the Warsaw ghetto, immortalized their bravery in his diary entry of May 19, 1942:

These heroic girls, Haika and Frumka, are a theme that calls for the pen of a great writer. Boldly they travel back and forth through the cities and towns of Poland. …

They are in mortal danger every day. … Without a murmur, without a moment of hesitation, they accept and carry out the most dangerous missions. … Nothing stands in their way. Nothing deters them. … How many times have they looked death in the eyes? How many times have they been arrested and searched? … [T]hese girls are indefatigable. (Ringelblum 1942, published in 1974, 273–274)

Although Ringelblum predicted that “the Haikas and Frumkas” would be viewed as leading figures by future historians, surprisingly, they have received relatively little attention. (The notable exception is the unpublished M.A. thesis of Shimshi, 1990.)

The reasons for this neglect will be considered in the final section of this essay. First, we examine why the Jewish resistance needed kashariyot, who they were, and what they did. For convenience, the Hebrew words “kashariyot” (fem. plural) and kasharit (fem. singular), and the English translation as “couriers” and “courier,” are used interchangeably, even though the English terms do not capture the heroic connotation of the Hebrew words.

Why Did the Jewish Resistance Need Kashariyot?

When the Germans forced the Jews of Poland into ghettos, they not only segregated them from their Christian neighbors, but also cut them off from other Jews. The ghetto walls were designed to isolate the Jews from news, information, supplies, and assistance that might help them survive. To overcome that paralyzing isolation, the Jewish resistance developed a “secret weapon,” the kashariyot, who could break through the walls of the ghettos throughout the vast territory of prewar Poland, and who could deliver news, help, and hope.

In the early months after the German invasion of Poland, the young men and women who first set out on these reconnaissance missions were the leaders of pre-war Jewish organizations who wanted to re-energize the local members of their movements. But when the Germans instituted the death penalty for Jews found outside the ghetto—the exact date varied in different zones of German administration—it became more dangerous for the male leaders to travel (because Jewish men were circumcised and could be clearly identified as Jews). While the men began restricting their travel, the women continued, and the couriers became predominantly female.

But the death penalty for Jews who were found outside the ghetto increased the danger for the women kashariyot as well. They had to travel with false papers, disguised as non-Jews, and had to rely on forged travel permits and sheer chutzpah to bluff their way through multiple police inspections, document checks, and border controls. They were always at risk of being unmasked, and always under the threat of death. It was a task that required great courage, quick wits, and nerves of steel.

When a kasharit arrived in a ghetto, she immediately sought out the local members of her movement. The news of her arrival quickly spread through the underground grapevine, and the members rushed to greet her. Everyone had family and friends in other ghettos, and they wanted to know what was happening to them. They were also eager to learn about recent events and to devour every precious word in the underground newspapers, letters, and bulletins she carried. The kasharit often assumed a motherly role and some of the local members just wanted to be close to her, to touch her and to hug her—as if they needed to be sure she was really there, and that the movement was really functioning. They all knew the risks she had taken to reach them, and they basked in the reflected glory of her success in breaking through the German barricades. In the early days of the German occupationm the kashariyot also conducted educational seminars, with inspiring lessons from Jewish history, and held all-night meetings to organize local programs.

The kashariyot were also symbolically important: they were living heroes, the personal embodiment of Jewish resilience. Some of them had already acquired a legendary status at that time, and they had an awe-inspiring ethereal aura. Their sheer presence was like “a blessing of freedom … a beam of light.” These were the words that were used by Rozka Korczak, a leader of the Jewish underground in Vilna (Vilnius), to describe the emotional response of her besieged colleagues in the Vilna ghetto when Tosia Altman, one of the most famous kashariyot/leaders from Warsaw, arrived in December 1941:

Tosia came.

It was like a blessing of freedom.

Just the information that she came.

It spread among the people. …

As if there were no ghetto. …

As if there was no death around.

As if we were not in this terrible war.

A beam of love.

A beam of light.(Korczak 1965, 31)

Who Were They?

Most of the kashariyot shared five basic characteristics. First, and most important, they were already active in, and often recognized as leaders of, a youth group affiliated with a specific Jewish organization. These organizations ranged from Zionist youth groups (such as Dror, Akiva, and Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir) to major political parties (such as the Jewish-Socialist Bund and the Communist party).

The young women who were recruited to become kashariyot were deeply committed to and identified with their organization and were asked to be couriers for that specific movement. It is difficult to convey the intensity, passion, and pride with which many young people defined themselves as “a member of” a particular movement. The movement’s ideology defined their goals; its leaders were their role models; and its members were their closest friends. As the war progressed, and as many young people lost their families, these movements became surrogate families and the center of their lives.

Because these movements inspired such ardent devotion, the kashariyot were, like other members, proud to demonstrate their loyalty by carrying out missions for the movement. This close identification between the individual and her movement explains why the kashariyot were known as couriers for a specific group and why their first missions were aimed at finding and energizing members of their own movement in each ghetto.

The second characteristic of the kashariyot was their physical appearance—they did not look distinctively Jewish and could blend into the Polish population. While it helped to have blond hair and blue eyes, blending into the local population required much more than the color of one’s hair or eyes. It involved the totality of one’s appearance, including one’s clothing, gestures, and demeanor.

Because most Jews in Poland grew up and lived in a Jewish community, their customs, manners, language, and modes of behavior were different from those of non-Jewish Poles. As a result, as Nechama Tec noted, most Polish Jews “felt like strangers in the world of the other” (Tec 1986, 36). In contrast, many of the young women who became kashariyot had more exposure to the non-Jewish world because they had lived in Polish neighborhoods or had attended Polish schools and were familiar with the styles and rhythms of daily life among their Catholic neighbors.

Third, the young women who became kashariyot typically spoke fluent Polish and did not have a Jewish accent. In contrast, most Jews in Poland grew up in Yiddish-speaking homes and communities. (In fact, in the 1931 Polish census, seventy-nine percent of the Jews listed Yiddish, not Polish, as their mother tongue.) Although most of these Jews also spoke Polish, many spoke it with a Jewish accent, or inflection, or with a style of speech that made it easy for gentile Poles to identify them as Jews. Because one could not interact with others without talking, the way one spoke Polish was critical for passing as a non-Jew and, as such, it also affected one’s self-confidence. Hence the ideal courier was someone who had grown up speaking colloquial Polish and did not have to worry about how she formed each sentence.

Fourth, most kashariyot were in their late teens and early twenties, as were most of the other young men and women in the Jewish resistance. As young people they were more likely to be strong, energetic, and idealistic. They were also more likely to be single and therefore less likely to be constrained by primary responsibility for children or a spouse.

Fifth and finally, most kashariyot were female because the leadership of the Jewish underground explicitly preferred and selectively recruited women to be couriers. Their rationale was not only based on the above noted physical disadvantage of Jewish men (who were marked by their circumcision) but was also based on the social and psychological advantages of being a Jewish woman in wartime Poland. For example, the social definition of appropriate male and female roles allowed women more freedom in public spaces. It was considered normal for a young woman to be out shopping and walking in the streets during the day, while a young man who was walking around (and not working) was suspect and was more likely to be stopped and questioned by the police. Those routine checks meant that male couriers were subjected to greater scrutiny and were more likely to be caught. In addition, male couriers faced the risk that hung over all young men in Poland: they were more likely to be arbitrarily picked up for forced labor.

A second social advantage was the greater exposure that some Jewish girls had to the non-Jewish world through Polish schools, as noted above. Because a Jewish education was considered more important for boys, many Jewish boys were sent to special Jewish schools, the Lit. "room." Old-style Jewish elementary school.heder and the yeshivah, while their sisters were sent to the “inferior” Polish schools where they learned Polish literature, customs, songs, prayers, and manners, along with their colloquial Polish. Some Jewish girls also acquired non-Jewish friends and acquaintances who might be willing to help them in the future.

Another social advantage was rooted in the traditional upbringing and “feminine” skills that were encouraged in young girls—such as being sensitive to the feelings of others, worrying about how others were reacting to what one said or did, being attuned to their nonverbal cues, and intuitively responding to others’ needs and wishes—and all of these skills were critical for a kasharit.

A final social advantage was the “natural appeal” of a young woman in dealing with both Germans and Poles. There are many instances of seemingly miraculous accomplishments by a kasharit who appeared to be “just a young woman asking for a favor”; Hasia Bornstein escaped from an inspection when she was carrying a laboratory for forging documents because she appealed to a guard and “looked so innocent”; Liza Czapnik was saved from walking into a massacre by a peasant woman who responded to her large blue eyes and “little girl looks”; Bronka Klibanski simply asked men who looked like gentlemen to buy her train tickets and carry her suitcases—when she was smuggling guns and ammunition—because her smile and elegant bearing inspired men to be chivalrous; and Bela Hazan received special travel passes from the Gestapo officers who employed her because she looked like the picture-perfect German girl with her long blond braids—and all the officers trusted her.

It is worth noting, however, that most couriers explicitly avoided sexual enticement, not only because of their traditional upbringing and mores, but also because it was “just too dangerous”; the last thing they needed was a man who wanted to know more about who they were, or what they were doing.

Their Four Missions

The specific tasks of the kashariyot changed as the Jewish resistance responded to shifts in German policy. Because German policies were instituted in different areas at different times, it is not possible to link these missions to a uniform set of dates for the entire territory of pre-war Poland, Lithuania, and parts of Russia. However, we can say that the kashariyot were involved in the following four missions during the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe.

When the ghettos were first established and most Jews were confined behind their walls and gates, the Jewish resistance (and the kashariyot) focused on contacting their members and improving conditions in the ghettos. However, once they realized that the Germans were planning mass murder and were going to totally obliterate the ghettos, they shifted gears and embarked on their second mission—an all-out effort to warn the Jews in far-flung ghettos and to urge them to resist. The kashariyot’s third mission focused directly on mounting that resistance. They spearheaded activities outside the ghetto by locating and smuggling arms and ammunition, gathering intelligence, establishing contacts with non-Jewish allies, and providing safe houses, false papers, and escorts for other members of the Jewish resistance who were working on the Aryan side. Their final mission focused on rescue and saving lives. In the last days of the ghettos, the kashariyot helped Jews escape from the ghettos and supplied them with false papers and places to hide. The kashariyot also supported them and their caretakers financially, and sustained them with visits, news, messages, and moral support.

While it is analytically useful to delineate these four discrete missions, it is important to reiterate that they did not begin or proceed in a uniform manner across and within different zones of German administration. Because the German policies varied, the specific tasks and priorities of the kashariyot also varied as they continuously responded to local conditions.

First: Making Contact and Sustaining Life in the Ghetto

When the prewar political and Zionist groups reconstituted themselves in the ghettos, they believed they would survive the German “occupation” of Poland. Once they had gathered and reorganized their own members, they reached out to help others survive—and to help them live with dignity—by setting up social welfare projects in the ghettos, such as underground schools, soup kitchens, illegal newspapers, educational seminars, public lectures, and cultural events. For example, the Dror underground set up secret (and illegal) classes in the Warsaw ghetto to give children a purpose, dignity, and hope.

At the same time, several groups sent couriers to the Aryan side of their own cities and towns to find food and other supplies to smuggle into the ghetto. Many of the kashariyot also engaged in local reconnaissance. They gathered information about German activities in nearby ghettos and established channels for future information and assistance. In addition, several young women who later became couriers started to master the art of smuggling: they embarked on private acts of resistance to keep their families alive by smuggling food into the ghetto.

With hindsight, we see that this initial period provided the kashariyot with critical training and experience. They studied the routines of the guards at the ghetto gates and learned when and how they could get out; they prepared their documents, dress, and appearance so that they could pass as non-Jews and work on the Aryan side; they rehearsed the “cover story” that would camouflage their real purpose and honed their techniques for smuggling illegal goods into the ghetto; and they found safe rooms and places to meet outside the ghetto, and a few people they could trust to help them in the future. These experiences also empowered them psychologically: they learned that they could succeed in outwitting the Germans.

Second: Carrying the Warning and Urging Resistance

The second, and most critical, mission of the kashariyot required them to shift gears. In fact, it required a major change in their strategy, a change inspired by terrifying news. In June 1941, when the Germans launched a surprise attack against their Soviet “allies,” German mobile killing units began mass shooting operations in which entire Jewish communities were murdered in a single day. While these massacres were highly secret operations, like those carried out in the Ponary forest near Vilna (in September 1941), the shocking news eventually reached the leaders of the Jewish underground in nearby communities. To their credit, they slowly began to understand that the killings were not isolated events: they were part of a comprehensive German plan to annihilate the Jews.

The Jewish underground leaders also realized that if the Germans were indeed planning genocide, there was no point in helping people cope with the hardships of the ghetto. All their efforts to sustain schools, soup kitchens, and culture were futile if no one could survive. In fact, if all Jews had already been sentenced to death, the only thing that mattered was finding a way to warn them about the Germans’ plans. Relaying that warning was clearly a job for the kashariyot. It became the most urgent priority of the Jewish underground and the most important mission of the kashariyot.

It was Abba Kovner, a leader of the Jewish underground in Vilna, who first dispatched the couriers with the news of the murders—and the call for resistance. It was not by chance that the news came from Vilna. The Jews in Lithuania were on the front lines of the German invasion (in June 1941) and they were among the first to be massacred by the German killing squads. Abba Kovner was one of the first leaders to hear—and to believe—an eyewitness who had escaped a mass killing at Ponary, and he was one of the first to understand what her story meant. In his famous speech calling for armed resistance in Vilna (on December 31, 1941) Abba Kovner declared: “Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter. … It is better to die as free men fighting. … Let us defend ourselves to the very last breath.”

It was Kovner who dispatched the first couriers to Grodno, Bialystok, and Warsaw, and each of them carried the carefully copied text of his speech to read as their call for resistance. (That is why Kovner’s dictum “Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter” appears in so many survivor accounts.)

It was hard for the kashariyot, who had always encouraged others to believe in life and hope, to find themselves traveling the same dangerous routes to speed the news of impending death. It was as if their world had turned upside down, and the propelling energy of their spirited optimism had to be transformed into unflinching grim pessimism. If they wanted to be effective, their descriptions had to be detailed and specific. But it was psychologically burdensome to repeatedly describe the gruesome scenes of mass murders. In addition, they themselves were forced to witness more German atrocities: they were often the only Jewish eyewitness to the anguish and end of entire villages and longstanding Jewish communities. While they felt compelled to bear witness, remember, and “record” everything they had seen for posterity, they also bore the psychological burden of keeping those memories alive (Gutman, 1963).

It was not only hard for the kashariyot to carry the news of the killings; it was also difficult for others to hear—and to believe—their reports. How could anyone believe that families who were told to bring bedding and clothing for “resettlement” were instead taken directly to be shot and buried in mass graves?

We now know that the Germans went to great lengths—using both secrecy and deception—to disguise the killing sites and to prevent the Jews from learning about the mass murder. If the Jews in each ghetto believed they were being resettled, they would be caught unaware and would not mount any resistance. But if the kashariyot were able to reach the ghetto before the deportations began, and if they were able to warn the Jews that the trucks and trains were really taking them to killing sites, the Jews would be more likely to resist being deported. That is why the Germans were eager to hide the mass killings, and that is why the Jewish underground was so eager to get the kashariyot out to warn the Jews. Both sides understood the critical importance of this news, and both sides predicted that knowledge of the mass murders would thwart the German plans.

Although that reasoning sounds straightforward in hindsight, it is important to underscore just how difficult it was for the kashariyot to convince the Jewish leadership in each ghetto that they themselves were in imminent danger. For example, Bela Hazan, the Dror courier who was sent from Vilna to Grodno in January 1942, reported that the Grodno Judenrat “did not believe” what she described, even though she brought authoritative information on the massacres in Vilna and Ponary.

One source of the Jewish leaders’ inability or unwillingness to accept the warnings about mass murder was the sheer magnitude of the crime: it seemed outside the realm of human behavior. As the Dror courier Bronka Klibanski explained, the Grodno Judenrat simply “could not believe such a policy could exist … because it was so inhuman … what civilized society, even in wartime, would kill an entire people?” (Klibanski interviews, 1993 and 1994).

A second source of skepticism was that the Jewish leaders continued to assume that German policy was based on some form of “rationality” or “rational calculus”: In each ghetto, the Jewish leaders had specific reasons why what happened in Vilna—if it did indeed happen—could not happen in their ghetto because the killings would not be economically or politically or practically rational (for the Germans). That was the reaction that Haika Grosman encountered on her first mission to Warsaw in January 1942. Grosman was a national leader of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir who was sent to Warsaw as the first official representative of the newly formed United Partisan Organization of Vilna. Hers was a high-level mission to brief the Warsaw Jewish leadership on the mass murders in Vilna and to convince them to organize armed resistance. The national leaders of most of the major Jewish organizations in Poland came to the Warsaw meeting with Grosman. But they dismissed her warning about the peril they faced because, as the Bund representative told her, it would not happen in Warsaw because Warsaw was the capital of Poland and the Germans would not risk the world-wide exposure of killing close to a half-million Jews in the center of the capital (Grosman, 1987: 74–79).

Similarly, in Bialystok, the head of the Judenrat, Ephraim Barash, assured Grosman that the Germans “would not dare” do what they did in Vilna because the factories in the Bialystok ghetto produced essential uniforms for the German army (Grosman 1987, 64). Barash insisted that the Germans would never cut off their own supply lines: “They need us.”

Thus, the biggest challenge the couriers faced was breaking through such “paralyzing illusions” (Klibanski, 1998). It is difficult for anyone to believe that he or she is going to be killed for no reason at all. And those beliefs were cynically exploited by the Germans who were, after all, masters of the art of skillful deception. In fact, in light of all the obstacles the kashariyot faced, what is surprising is how successful they ultimately were, and how much anti-German resistance their reports ultimately inspired.

The information and exhortations of the kashariyot had a much more immediate impact on the young men and women who were to become the leaders of the ghetto uprisings. For example, before her frustrating meeting with the Warsaw ghetto establishment, Haika Grosman first met with Mordechai Anielewicz (the future commander of the uprising) and the other leaders of her movement, Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, in their “kibbutz” headquarters in the ghetto. There was great excitement and they stayed up all night talking: they “understood” the meaning of the murders in Vilna, and they understood the need for armed resistance. However, at that time (in January 1942), they and their Dror partners in the would-be revolt, Yitzhak Zuckerman and Zivia Lubetkin, were still trying to figure out “when and how.” One year later, in January 1943, Anielewicz and Zuckerman were leading the first uprising in the Warsaw ghetto.

Grosman’s meeting with the Zionist youth in Bialystok was also “exhilarating.” When she read them Abba Kovner’s speech they were ready to act. While it would take some time before the Bialystok resistance was organized and unified, a core group of young people was already on board.

There was one notable exception to this pattern of positive responses from the Zionist youth groups on one hand, and resistance from the Judenrat and the “ghetto establishment” on the other hand. In the Kovno ghetto, the Judenrat immediately understood the dire warnings brought by the courier Irena Adamowicz in the summer of 1942. Irena was a non-Jewish member of the Polish Scouts who became an important courier for the Jewish resistance in Warsaw and Vilna. The Jews in Kovno were so completely isolated that they did not know about the killings in nearby Vilna. When Irena told them about the mass murder in Ponary and read Abba Kovner’s speech calling for armed resistance, the Kovno Judenrat responded immediately and started to plan and organize resistance. This exemplary Judenrat worked directly with the underground JFO (the Jewish Fighting Organization) in the ghetto. They directed the Jewish Police to provide military training for the fighters and to teach them how to use weapons. Later on, they also facilitated smuggling arms into the ghetto and, in 1943, they helped young people escape from the ghetto to join the partisans. Clearly Kovno provides one example of the direct and immediate impact of the warnings of a courier.

Third: Mounting the Resistance and Getting Weapons

The third sphere of courier activities, which overlapped chronologically with the second, focused on resistance. Because the kashariyot had developed the expertise and contacts for working outside the ghetto, they became responsible for a wide range of difficult and dangerous tasks that had to be undertaken on the Aryan side. At the top of this list was the all-important job of acquiring guns, explosives, and ammunition for the ghetto revolts and finding a way to smuggle them into the ghetto. The kashariyot also smuggled money, messages, supplies, and ammunition to groups of Jews planning resistance in factories, prisons, camps, and distant ghettos. At the same time, they provided critical guidance and logistical support for other leaders of (and operatives in) the Jewish resistance who were working on the Aryan side.

Securing guns and ammunition was for many kashariyot their most difficult, most frustrating—and most important—assignment. As Vladka Meed, a Bund courier in Warsaw, wrote: “[T]he main objective of our mission on the Aryan side—the goal for which we endured constant danger [and] hid like frightened animals … was to obtain arms for the resistance in the ghetto” (Meed 1993, 94).

In retrospect, it is difficult to believe that the Jewish resistance had virtually no weapons when they decided to fight the Germans. Yet this was true in each of the major ghettos. In Bialystok, for example, the underground had only one rifle by the summer of 1942. The rifle had to be carried to each unit of would-be fighters—always at great risk in the ghetto—so that each group could be trained with a real rifle (Grosman 1987, 967). In Vilna the fighters shared a single snub-nosed revolver for their training, “which was passed hand to hand like an icon” (Cohen 2000, 59). In Cracow, they did not have a single gun (Draenger 1996, originally published in 1946).

In the judgment of both the participants at that time and later historians, the lack of weapons was the single biggest obstacle for the Jewish resistance. The Jewish leaders assumed the Polish underground was going to help with arms and military support but, as Antek Zuckerman wrote with great bitterness, the Jews were betrayed.

It was in this bleak environment that the kashariyot were sent out to find weapons—on their own. Time was running out and the resistance desperately needed guns and ammunition. This was the ultimate challenge for the kashariyot. It was the point at which their expertise and Aryan contacts were most needed.

Each kasharit has a dramatic story to tell about her efforts to locate, obtain, and transport weapons. And each of those who survived had more than one close brush with death. Bronka Klibanski, the Dror courier in Bialystok, was smuggling a revolver and two hand grenades hidden in a loaf of country bread in her suitcase. At the train station a German policeman asked her what she was carrying. By “confessing” that she was smuggling food, she managed to avoid having to open her suitcase. Surprisingly, her “honest confession” also evoked a protective response from the policeman who instructed the train conductor to take good care of her and to be sure that no one bothered her or her suitcase.

Itka Szwajger, a young doctor who was a Bund courier, was also extraordinarily lucky. One day she was carrying ammunition in her bag when she was stopped by an ordinary police patrol in Warsaw. The officer ordered her to open her bag. She smiled and opened the bag wide to show him the potatoes that were on top. When he saw the potatoes, he waved her on.

Hela Schüpper, the kasharit for Akiva, was sent to Warsaw to buy guns for the Cracow resistance. Knowing that she would be under scrutiny for twenty hours on the trains, she prepared her appearance with great care. She dyed her hair to be “really blond,” borrowed an outfit from the mother of a non-Jewish friend so that she would look “very Polish, very stylish and very mature,” and splurged on an elegant handbag. Her costume gave her the air of a carefree, chic, cultured lady off to an afternoon of theater. When she received the weapons, she carefully taped the five pistols to her body, under her clothing, and hid the explosives and bullets in her fashionable bag. Although her stomach was tied in knots, her performance was a success and she returned to Cracow by train without ever being searched (Schüpper interview, 1994). Gusta Davidson describes Hela’s triumphant return with the guns: “No one had ever been greeted with the outpouring of affection that was showered on Hela…it was truly a miracle…” (Davidson, 70–71).

Hasia Bornstein, the kasharit who delivered a machine gun and six hundred bullets to the partisans in the forest near Bialystok, was also welcomed as a savior and celebrated with an emotional outpouring of affection and gratitude. There was such excitement and rejoicing that the partisans refused to let her leave to return to the city.

These kashariyot were the lucky ones—and the exceptions. Most of the kashariyot, especially those who were sent on missions to buy and smuggle guns, did not survive. In fact, the tragic arrest of two of the most talented and most experienced kashariyot, Lonka Korzybrodska and Bela Hazan, was triggered by Lonka’s carrying four pistols to Warsaw. Because Lonka and Bela looked “so good,” and because they were so multi-talented, everyone assumed they would always find a way to get through, and they were routinely sent on the most dangerous missions. When they were arrested, they were, ultimately able to maintain their Aryan cover, despite the fact that they were caught with guns, and neither one was ever unmasked as a Jew. Bela, who was arrested on April 12, 1942, was also carrying Hebrew materials hidden in her long blond braids, but she was able to get rid of them in the bathroom before she was thoroughly searched. Although they could not explain away the guns, the Gestapo assumed they were working for the Polish resistance and tortured them for information on their contacts. But neither Bela nor Lonka broke. After months in prison, they were eventually sent to Auschwitz as Poles (while they would have been shot if they had been identified as Jews). Lonka died of typhus in Auschwitz in March 1943. Bela survived to tell their story (Hazan interview, 1994).

Courtesy of Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

Fourth: Saving Lives: Rescue as Resistance

The fourth mission of the kashariyot was to save Jewish lives. Once it became clear that the ghettos were being liquidated, the kashariyot were charged with the massive task of saving as many Jews as possible. Aware that they were engaged in a race against time, they embraced the mission with passion: they escorted and aided children and adults in escaping from the ghetto, located rooms for them to stay on the Aryan side, prepared their new identity cards, and supplied them (and those who were hiding and helping them) with financial support.

Each of these tasks was enormously complicated and dangerous. One never knew if someone had placed an advertisement for a reasonable room to set a trap, or if the landlord would change the published price after the escapee arrived. In addition, the arrangements were always falling apart and had to be redone: a neighbor would become suspicious, or a landlord would become nervous, or someone would be discovered by a blackmailer. The psychological stress was relentless. Adina (Itka) Szwajger, the Warsaw doctor who was a courier for the Bund, said she could feel the shivers of fear and anxiety spread throughout her body from the moment she hid the forged ID cards in her handbag or tucked them into her clothes: “It was a cold feeling … an awareness that from that moment on every accidental search in the street might be the end” (Szwajger, 1990: 81).

The kashariyot were also responsible for guiding and protecting the leaders and members of the Jewish resistance who were working undercover outside the ghetto. The kashariyot helped them plan and carry out their missions, supplied them with false papers and certificates of employment, secured “safe” houses, rooms, and apartments for their missions, and served as their official emissaries and escorts.

Because it was hazardous for male leaders of the Jewish resistance to be on the streets on the Aryan side, they were typically accompanied by a kasharit, who furnished a cloak of respectability, since a couple always looked more innocent than a single male. The kasharit, who usually spoke more colloquial Polish and had already developed “street smarts” outside the ghetto, could serve as his local guide and “front person.” For example, she would often be the one who spoke when they had to purchase train tickets or rent a flat.

In the final days of the ghettos, there was intense pressure on the kashariyot to complete two critical and urgent tasks at the same time: to secure weapons and to rescue Jews. Because of the high mortality rate of the kashariyot, there were not enough experienced couriers to carry out these crucial tasks, and each movement had to continuously recruit new kashariyot. Most of these new kashariyot remained in the local area, and they immediately became involved in rescuing children and adults from the ghetto. The intense and exhausting efforts required to find non-Jews who were willing to provide shelter, and the constant pressure on the kashariyot to be alert, vigilant, and available, meant that they were always under stress and always on the brink of a disaster.

The kashariyot in Warsaw also had to cope with a particularly dangerous and obnoxious group of Poles, the schmalzowniks—the extortionists and blackmailers who terrorized the Jews on the Aryan side. Itka Szwajger, the Bund courier in Warsaw, never understood how the extortionists managed to find the addresses of people who were hidden, but a blackmailer’s visit to one of her charges was “the ultimate disaster.” Even though the blackmailer would promise silence in return for a substantial payment, he would return again and again until the victim had nothing left. As soon as a kasharit learned that a blackmailer had “burned” one of her flats, she had to quickly find a new place and camouflage the move.

It would be reasonable to assume that the kashariyot would not have any personal difficulties with blackmailers because they were not likely to be identified as Jews. However, their work required them to be seen in places (such as leaving the ghetto) that made them suspect. For example, Haika Grosman was approached by an extortionist who saw her leave the Warsaw ghetto. She was carrying important documents and a substantial amount of money to buy guns for the Vilna resistance. The man followed her, and she could not deter him by yelling and cursing him. Haika finally scared him away by announcing she was going to complain to a German SS officer standing nearby.

After the ghettos were liquidated, the kashariyot who survived continued their resistance activities. They carried out ever more daring missions to save and support Jews who had escaped from the deportations or were still in forced labor, camps, or hiding in the forests or the city. Some of them also worked with Jewish or Russian partisan groups and with the Polish resistance.

Because every Jewish organization was devastated by the loss of members in the final liquidation of the ghettos, those who survived began working together despite the fact that they were previously affiliated with different groups. For example, one extraordinarily successful group of kashariyot who formed the core of a united “anti-fascist” group in the Bialystok area, were originally from three different movements: Hasia Bornstein, Haika Grosman, and Rivka Madajska from Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Bronka Klibanski from Dror, and Liza Chapnik and Anya Rod from the Young Communists. Their united group worked with Marylka Rozycka, the kasharit for the Jewish partisans in the forests near Bialystok, to accompany escaping Jews to the partisan hideout and to help the partisans acquire weapons, food, warm clothing, medical supplies, and information. When the Soviet partisans moved into the area, these kashariyot became their lifeline, providing them with critical maps and strategic data on German installations in the city, as well as with bullets, blankets, medicine, and food. One external validation of the extraordinary accomplishments and heroism of these young women is provided by the recognition they received from the Soviet partisans and their government after liberation: all the kashariyot in the Bialystok group were honored as “national heroines” of the USSR.

Evaluating the Importance of the Kashariyot

How important were the kashariyot in the larger context of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust? The leaders of the Jewish resistance, who were in the best position to evaluate the role of the kashariyot, consistently placed them in the indispensable core of the Jewish resistance. For example, Zivia Lubetkin, who was in the central command of the Warsaw ghetto uprising, concluded that “one cannot possibly describe this work of organizing the Jewish resistance, or the uprising itself, without mentioning the role of these valiant women” (Lubetkin 1981, 75). Similarly, Mordechai Tenenbaum, the commander of the Jewish uprising in the Bialystok ghetto, described the missions of the fearless Dror kasharit Tema Sznajderman as the real “center” of resistance activities. Both the descriptions of individual kashariyot and the accounts of their accomplishments are filled with glowing accolades and a reverence that approaches awe. For example, Yitzhak Zuckerman, a commander of the Jewish fighting organization in Warsaw, described the “intelligence, wisdom and charm” of the Dror kasharit Lonka Korzybrodska as like those of “a high priest … with ‘magic,’” her long blond braids arranged “like a halo on her head” (1985, 68–69).

The reverence for the kashariyot was not limited to words. They were also treated with great respect and deference by the leaders of the Jewish resistance at that time. For example, at the historic meeting that united the Jewish organizations in Vilna on December 31, 1941, after Abba Kovner first delivered his speech calling for armed resistance in Yiddish, he turned to Tosia Altman, the kasharit/leader who had just arrived in Vilna on a mission from Warsaw. Tosia then delivered the same powerful speech in Hebrew. The symbolic recognition and status accorded to Tosia Altman was not only a reflection of her personal stature as a kasharit/leader from Warsaw. It was also an indication of the legendary importance of the kashariyot as those who would carry the call for resistance. In fact, as we have seen, the kashariyot literally carried the text of Kovner’s speech and delivered its powerful message in other ghettos.

The tribute to the kashariyot written by the eminent historian Emmanuel Ringelblum in the Warsaw ghetto in May 1942, cited in the opening paragraphs of this entry, is another indication of the importance of the kashariyot and their courageous work. Although Ringelblum is cautious, even in a secret diary, not to disclose too much, the two first names he mentions show that he knew the real names of at least two legendary kashariyot, Haika Grosman and Frumka Plotniczki, was aware of the vast scope of their dangerous missions, and was proud of their amazing accomplishments. His words also reflect his unbounded admiration for their personal courage and bravery. Finally, and perhaps most significant, Ringelblum, who was the foremost historian in the Warsaw ghetto, also accorded the kashariyot a central role in history—a “glorious page in the history of Jewry during the present war: and the Haikas and Frumkas will be the leading figures in this story.”

We may therefore well ask why the kashariyot, who were clearly regarded by their contemporaries as central and important participants in the Jewish resistance, have rarely been accorded that status in subsequent historical accounts. Why would they be considered heroic at the time, but be neglected thereafter?

While it is possible to attribute the neglect to ignorance, or to poor scholarship, or to sexism, it is also possible that modern historians have (unconsciously) relied on their own assumptions about who should be considered a hero, and they have, on the whole, restricted the term to those who fought the Germans in the ghettos. Although some kashariyot—like Frumka Plotniczki, who led the ghetto fighters in the Bendzin ghetto—did engage in combat, most of them did not. If this, then, is the line that has separated the kashariyot from those who are defined as heroes, we need to examine the rationale for this line and to ask whether it is appropriate.

One rationale for recognizing only “the fighters” as heroes is that they were the ones who risked their lives. It is clear that all of those who fought in the ghetto revolts were willing to risk their lives to fight for “Jewish honor.” We know that most of them assumed that they were going to die in the battle. They did not fight to stop or defeat the Germans or to “win” the battle, because they knew that was not possible. Their fight was largely symbolic—they fought for honor, and for revenge, and to disrupt the Germans’ plans and take control of how and when they died.

However, as this article has shown, the kashariyot were also willing to risk their lives: they were in constant danger and always under the threat of death. In addition, like the fighters, they assumed that they were going to be killed—none of them expected to survive. When Lisa Chapnick was chastised for undertaking a very dangerous mission alone, she explained that she did not want to lose anyone else because she had assumed that she would be killed. Thus, if we define a hero as one who has risked their life, then the kashariyot should be considered heroes because they certainly took that risk.

But perhaps it is assumed that the “fighters” were in greater danger and exposed to the risk of death for a longer period of time. However, when we consider the amount of time the fighters were at risk—or even the specific number of days or hours that they were “engaged” in a life-threatening situation, we once again see that the kashariyot were in life-threatening situations for as much—and typically for much longer periods of time—as those who fought in the ghetto revolts. In Warsaw, for example, the ghetto fighters were at risk, using the most liberal definitions of the time involved, for five months (January to May 1943). In Bialystok, they were at risk for, at most, three weeks (in August 1943). In contrast, most of the kashariyot faced the risk of death for more than six months, and many of them faced the risk for several years.

Another possible rationale for honoring only the “fighters” as heroes is that we assume that they were the ones who lost their lives for the cause. While we know that most of those in the ghetto were, in fact, killed in the uprising and its aftermath, it is also clear that most of the kashariyot were also killed in the line of duty. However, because most kashariyot travelled alone, under the cloak of anonymity and secrecy, and because they intentionally left behind anything that might reveal their Jewish identity, we do not have the same level of knowledge about when or where or how they were killed. But we do know that most of them did not survive. For example, of the twenty-three women who started out as couriers in the Grodno-Bialystok area, eighteen lost their lives in the war.

Although one might assume that the “ghetto fighters,” in contrast, were all killed in the battle, in fact, some of those who fought in the ghettos also managed to survive. Yet those who survived have always been recognized as “fighters” and are still considered “heroes” of the uprising.

In addition, a closer analysis of some of the activities of the fighters reveals that some of the “fighters” did not actually “fight” in the battle in the ghetto. Instead, some of them were engaged in the same type of strategic missions as the kashariyot. For example, Yitzhak Zuckerman, one of the commanders of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt, was on the Aryan side during the uprising (in April 1943) because he was desperately trying to obtain more arms for the ghetto fighters.

This analysis should lead us to conclude that the kashariyot took the same risks and suffered the same consequences as those who fought in the ghettos, and that they are equally deserving of the title of hero. It is, however, still possible that this type of reasoned analysis may nevertheless be at odds with the popular judgment that accords more honor to those we call fighters, or to those who had guns, even if they never fired them. Is the lack of recognition given the kashariyot simply due to the fact that they were not “conventional soldiers”? Or because they did not (usually) have guns? If so, is it appropriate to restrict the definition of heroes to those who used guns and engaged in direct combat with the Germans? Were they, in fact, more valuable to the Jewish resistance?

The question is itself somewhat inappropriate because most of those who fought in the ghetto revolts did not have guns. In fact, because guns were in such short supply, most people in the ghetto fought with homemade weapons, like Molotov cocktails, and with their hands and fists and bodies. But putting aside this intrusion of reality, we can ask whether those who did have guns, and who did fight the Germans in the ghetto, were more valuable to the Jewish resistance than the kashariyot.

The leaders of the Jewish resistance in both Warsaw and Bialystok faced precisely that question in the last days of the ghettos and their answer is instructive. When the final liquidations and uprisings began, the leaders had to decide whether the kashariyot should remain in the ghetto to fight in the uprising, or if they should leave the ghetto to continue their work on the Aryan side. In both cities the leaders made the same decision: They “ordered” the kashariyot to leave the ghetto (or to remain outside the ghetto) because they considered the kashariyot’s missions on the Aryan side—i.e., securing weapons and rescuing others—as more important and more valuable to the resistance than having them fight in the ghetto.

This analysis underscores the fact that it is inappropriate to superimpose today’s views of who and what is heroic if we are trying to understand Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. The kashariyot were not conventional fighters: they did not use conventional weapons and they did not fight in conventional battles. Their times called for daring innovations and different modes of fighting the Germans. But the kashariyot were clearly engaged in fighting the Germans and we deny them the heroic recognition they deserve if we impose inappropriate post hoc standards that disregard or diminish their heroism.

Clearly, the kashariyot were both essential and central to the Jewish resistance—whether one defines that resistance as a resistance of informing, persuading, and organizing others to resist, evade, or thwart the Germans—or whether one defines it as the armed struggle against the Germans. If they had done nothing else, their efforts to spread the news of the mass murders, and their effectiveness in mobilizing others, place the kashariyot at the very heart of the Jewish resistance.

Further, even if one limits the definition of resistance to the armed struggle, it is clear that the kashariyot, who spent months finding and buying weapons and smuggling them into the ghettos, were as essential as those who fired the guns and threw the Molotov cocktails. Both were exposed to death and both faced the risk of being killed in the line of duty. Those who fired the guns would not have had the guns to fire without the ingenious efforts of the kashariyot.

In summary, in terms of the criteria considered above—the exposure to risk and death, the amount of time at risk of death, and the loss of life in the line of duty—the kashariyot were more than equal to other participants in the ghetto resistance. It is, in fact, difficult to imagine a Jewish resistance during the Holocaust without them. It is therefore appropriate to correct the historical record to include what Dr. Ringelblum referred to as the kashariyot’s “glorious page” in the history of the Jewish resistance during the Holocaust.

Arad, Yitzhak. Ghetto in Flames: The Struggle and Destruction of the Jews of Vilna in the Holocaust. New York: 1982.

Cohen, Rich. The Avengers. New York: 2000.

Davidson Draenger, Gusta. Justyna’s Narrative. Amherst, MA: 1996 (originally published in Polish in 1946).

Fatal-Knaani, Tikva. Grodno is Not The Same: The Jewish Community of Grodno and its Vicinity During the Second World War and the Holocaust, 1939–1943 (Hebrew). Jerusalem: 2001.

Grosman, Haika. The Underground Army: Fighters of the Bialystok Ghetto. New York: 1987.

Gutman, Israel. Revolt of the Besieged: Mordechai Anielewicz and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1963.

Klibanski, Bronka. “In the Ghetto and in the Resistance: A Personal Narrative.” In Women in the Holocaust, edited by Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman. New Haven, CT: 1998.

Korczak, Rozka (Reizl). Flames in The Ashes (Hebrew). Merhavyah: 1956.

Lubetkin, Zivia. In the Days of Destruction and Revolt (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1981.

Meed, Vladka. On Both Sides of the Wall. New York: 1993.

Ringelblum, Emmanuel. Notes From the Warsaw Ghetto: The Journal of Emmanuel Ringelblum. Edited and translated by Jacob Sloan. New York: 1958, reprinted 1974.

Rotem, Simcha. Kazik: Memoirs of a Warsaw Ghetto Fighter. New Haven: 1994, 66

Shalev, Zivah. Tosia Altman: From the Leadership of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir to the High Command of the Jewish Fighting Organization (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1992.

Shimshi, Naomi. “The Communication Networks and the Couriers of the Pioneering Youth Movements in Occupied Poland” (Hebrew). M.A. thesis, University of Haifa, 1990.

Szwajger, Adina (Blady). I Remember Nothing More: The Warsaw Jewish Hospital and the Jewish Resistance. New York: 1990.

Tenenbaum, Mordecai. Pages From the Fire: Chapters of a Diary, Letters and Notes (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: 1947.

Weitzman, Lenore J. “Living on the Aryan Side in Poland: Gender, Passing and the Nature of Resistance.” In Women in the Holocaust, edited by Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weitzman, 187–222. New Haven, CT: 1998.

Zuckerman, Yitzhak. A Surplus of Memory: Chronicle of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Berkeley: 1993, 485.

Interviews:

Bornstein-Bielicka, Hasia. June 14, 1994, A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutz Lahavot ha-Bashan, Israel.

Chapnick, Lisa. June 1994, Tel Aviv. October 19, 2003, Beer Sheva. December 18, 2003, Jerusalem.

Folman-Raban, Chavka. July 9, 1993 and October 16, 2003, Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot, Israel.

Gweiser, Luba. December 16, 2003, Tel Aviv; Hazan (Ya’ari), Bela. June 20, 1994, Tel Aviv. October 20, 2003, Jerusalem.

Klibanski, Bronia (Bronka). June 12, 1993, June 21, 1994, and December 19, 2003, January 21, 2005, Jerusalem.

Kossover, Shoshana. December 17, 2003, Tel Aviv; Kovner, Vitka. October 19 and 20, 1997, Washington D.C.

Meed, Vladka. July 2002, New York.

Rotem, Simcha. June 6, 1994, Jerusalem.

Rod, Anya. October 19, 2003, Beer Sheva, and December 18, 2003, Jerusalem.

Ruttenberg, Vanda. June 23, 1994, Tel Aviv; Schupper-Rufheisen, Hela. June 18, 1994, Cooperative smallholder's village in Erez Israel combining some of the features of both cooperative and private farming.moshav or moshav ovedim Bustan ha-Galil, Israel.

Shimshi, Naomi. July 1994, Kibbutz Yagur, Israel, and October 2003, Kibbutz Lohamei ha-Getta’ot.

Silverstein, Leah. February 23, 2003, and May 22, 2005, Washington, D.C.