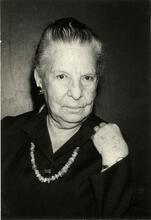

Hela Rufeisen Schüpper

The only member of her family and fellow resistance fighters to survive the Holocaust, Hela Schupper felt that she could only live in Palestine, where she could tell the story "of what happened to us… of the murder of millions, of life in the ghettos, of the unequal, impossible and heroic struggle against the Nazi beast," while also helping to "build Erez Israel."

Courtesy of Yael Peled

Born to a hasidic family in Krakow, Hela Rufeisen Schüpper joined the Zionist youth movement Akiva against her family’s wishes. When the Germans invaded Poland, Schüpper joined the Jewish resistance against the Nazis, becoming a key courier on account of her Aryan looks. She smuggled weapons and other vital supplies for the resistance between Warsaw and Krakow, only being captured after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was over. Schüpper survived Bergen-Belsen and moved to Israel after the war.

Early Life

One of five children, Hela (var. Hella) Rufeisen was born in Krakow on June 7, 1921, to Simha (née Rosenberg, 1896–1931) and Pinhas Schüpper (1896–1943). She had two sisters, Nehama-Halinka (1927–1942) and Miriam (1931–1943), and two brothers, Josef (1920–1943) and Heszu-Melech (1923–1942).

Schüpper grew up in a A member of the hasidic movement, founded in the first half of the 18th century by Israel ben Eliezer Ba'al Shem Tov.hasidic atmosphere. Her maternal grandfather had been a trusted assistant to the rebbe of Bobówa (Bobov). Her father was a cantor and ritual slaughterer. In 1931, when Hela was ten years old, her mother died shortly after giving birth to Miriam. Left with five young children to care for, her father gave Hela into the care of her grandmother. Even after he remarried, Hela stayed in the very religious home of her grandmother, her aunts, and her uncles. Schüpper attended the Polish public school where she was exposed to Polish religious patriotism that was in sharp conflict with the very religious atmosphere of her grandmother’s home. When she was fourteen, her grandmother died and Hela remained with her aunts and uncles.

Upon completing elementary school, she attended the Polish commercial high school. Instructors from the Women’s Organization for Military Training, a Polish nationalist organization, visited the school to persuade the girls to join their group. When Schüpper saw that no one was interested, she became ashamed of her classmates’ lack of patriotism and joined, whereupon other pupils followed suit.

The group’s meetings were devoted to culture, sport, riflery, and pistol practice. Schüpper was a member for two years until she was sixteen. She left demonstratively after a member of the Polish parliament, Janina Amelia Prystorówa, tried to have Jewish ritual slaughter abolished, ostensibly on humane grounds. Schüpper, however, saw this as an antisemitic act.

Joining Akiva

Schüpper’s friends had been trying for years to bring her into the Zionist youth movement. She decided to join Akiva when Shimshon Draenger (1917–1943), one of its leaders, assured her that although the movement was Zionist, it was not atheist. Interestingly, her family, who had not opposed her activity in the Polish nationalist youth movement since they saw it as part of her school activities, opposed her joining the Zionist movement because it was coeducational, advocated immigration to Palestine and was, they felt, remote from Judaism. One of her uncles described her membership in the movement as “unbecoming to a girl of good family.”

Considering herself independent because she supported herself by working in a laundry, Schüpper went to the movement’s summer camp against her relatives’ wishes. Faced with their anger upon her return, she announced that since her membership in the movement was not to their liking, she would leave home. Accordingly, she rented a bed in the home of two elderly women, with whom she lived for six months. Shimshon Draenger calmed her by reminding her that they would in any case be immigrating to Palestine in half a year. Severing all contact with her family, Schüpper made the movement her home.

Joining the Resistance

World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, but before the Germans entered Krakow on September 6, the members of the youth movement decided to flee eastward to the Soviet Union and afterwards to join the Polish army. Together with her brother Josef, Schüpper traveled some two hundred kilometers to Rozwadów, which they reached on the eve of the Jewish New Year. When the Germans caught up with them, they decided to return to Krakow, arriving after The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur 1940. After Josef was captured by Germans and badly beaten, he decided to flee eastward once again. This time he refused to take his sister with him, thinking her incapable of enduring the difficult journey.

In February 1941 the Germans announced that only fifteen thousand people would be able to enter the Krakow ghetto, which was to be opened on March 21. Of all her family, only Schüpper was permitted to enter. Since the rest of her family, including her father, his wife and her youngest sister, had moved to Wieliczka, she decided, with her counselors’ encouragement, to join Akiva’s Warsaw branch. Defined as a “place of refuge for young people who had left Krakow,” their apartment was sponsored by the Jewish Association for Social Aid (Zydowskie Towarzystwo Opeki Spolecznej, ZTOS). Most of the twenty-five members who lived there were from Krakow and Warsaw, while two were from Sanok. To support themselves they worked at various jobs until the afternoon, later conducting a wide variety of movement activities. They established a group of three hundred members whose activities included the study of Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, Jewish history, Hebrew, and literature.

As conditions in the Warsaw ghetto deteriorated and many people died of starvation and disease, the situation in the commune also became difficult. Matters took a dramatic turn after the great aktion of July 22, 1942, which continued on and off until September 12, with 265,000 Jews sent to the crematoria of Treblinka. This aktion sparked the establishment of a militant Jewish underground. Representatives of the three pioneer youth movements—Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir, Dror/He-Halutz, and Akiva—met on July 28, 1942 and decided to establish the Jewish Fighting Organization (Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, ZOB). Schüpper and Israel Kanal represented Akiva at the meeting. Schüpper conveyed the committee’s decision about armed struggle to her comrades, most of whom were in favor, well aware that they had to take orders from their leaders in Krakow, Dolek Liebeskind (1912–1942) and Shimshon Draenger.

Heroism and Smuggling

Schüpper now began her career as a courier in late July between Warsaw and Krakow and between Krakow and other branches of the movement. Dyeing her hair a lighter shade, she set out on the dangerous journey out of the ghetto, continuing by train to Krakow and into the Krakow ghetto—all without any identity papers. The Germans were not her only source of potential danger; she also had to beware of szmalcowniki, Polish blackmailers who extorted money from Jews who were passing as Aryans, threatening to hand them over to the Gestapo if they did not pay. Though the journey to Krakow was filled with “adventures,” she finally presented herself to Dolek Liebeskind and Shimshon Draenger, the leadership of Akiva. From them she learned of the underground established in Krakow and its connection with the Polish Workers’ Party (Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR), which was actually a Communist underground and which had undertaken to help them reach the forest. They had no weapons, but were promised that they would receive them from Warsaw.

The task of bringing the weapons from Warsaw fell to Schüpper, who reported to her comrades in Warsaw about developments in Krakow and the leadership’s decision that whoever had an Aryan appearance and could reach Krakow must do so and go to the forests to fight, while whoever could not leave the ghetto because of their Jewish appearance should join the fighting underground in Warsaw.

When Schüpper returned to Warsaw with these orders she learned that many of her friends had been deported in the aktion. The group had disbanded and moved living quarters as the ghetto shrank. Schüpper entered the ghetto toward evening as part of a returning work detail. She returned to Krakow together with two colleagues who wanted to join the fighters there immediately. Schüpper brought ten pictures of colleagues with her so that Shimshon Draenger, an expert forger, could prepare identification papers for them, enabling them to leave the Warsaw Ghetto and also join their Krakow comrades. This time, Schüpper was asked to bring weapons from Warsaw that a member of the PPR had purchased for them.

Schüpper again returned to Warsaw where she met with a member of the PPR and returned safely to Krakow two days later with the weapons hidden under her dress and the explosives hidden in her bag. In her diary Gusta Draenger described the excitement Schüpper’s return aroused, since some people knew what she was bringing:

Everyone waited tensely for the weapons, and one bright morning Hela returned from Warsaw, smiling, well-dressed and carrying a new travel bag. She walked with her own special confidence, head erect. … It seemed that nothing interested her except the attention and wonder her appearance caused. … As she traveled on the train, it would never have occurred to anyone that this young woman was a member of the underground. … Several times she traveled back and forth, each time entering the Warsaw Ghetto, where she ran the risk of being trapped for good. She was the first to volunteer as a courier in the movement. Her gift of talking to people and her good looks eased the way for her. … Those traveling with her never dreamed that she was smuggling weapons. … No one had ever been welcomed with as much excitement as Hela was now. … No one will ever understand how much we rejoiced over the weapons that had been obtained and which were now ours.

Nevertheless, on her way from Krakow to Warsaw Schüpper was arrested by a Polish police officer who suspected she was Jewish. She was in especial danger this time, since she was carrying the forged papers for her colleagues in the Warsaw Ghetto. Keeping her nerve and ability to maneuver, Schüpper insisted she was Polish and that she had to use the toilet urgently. Once there she flushed all the papers down the toilet. After three days of detention, the police released her as a Polish Catholic woman and even apologized. She entered the ghetto once more in her usual way, by joining a Jewish labor detail returning from work. Once again Schüpper collected photographs of comrades so she could return to Krakow and try to come back with identity papers forged by Draenger.

On her return to Krakow Schüpper encountered a great deal of underground activity there in preparation for a second exodus to the forest after the first failed attempt. Couriers such as Schüpper, Rivka Liebeskind (Vuschka), and others who looked Aryan were sent to various cities near the forests to prepare safe houses for the future fighters to use as exit points and also to serve as hideouts during aktions. Schüpper was first sent to Rzeszów to rent a room and then to Lvov, both to inform the comrades scattered throughout the various groups of the establishment of the Pioneer Fighting Movement and to distribute false identity papers so they could reinforce the Krakow group.

In October 1942 Schüpper was in Krakow, using forged papers identifying her as a Pole. Unknown to her, an aktion was taking place in the ghetto during which her younger brother Heszu-Melech was murdered and her sister Nehama-Halinka was killed together with all the children in the orphanage. She managed to save her youngest sister Miriam and hide her on the Aryan side in the home of the Polish janitor of the building where her grandmother was living.

On the eve of the operation, Schüpper received an order from Draenger to go to Rzeszów and not return until she was called, and to tell any other comrades she happened to meet to do the same. On January 17, 1943, Schüpper returned to Krakow to search for the comrades who remained after the Cyganeria operation. She met Gusta Draenger, who was searching for her husband Shimshon, already being held at the Montelupich Prison. Schüpper tried to persuade Gusta to come with her to Warsaw, but Gusta gave herself up when she learned of her husband’s imprisonment.

Return to Warsaw

On Schüpper’s return to Warsaw on January 18, she found an aktion and a minor rebellion in progress. Unable to enter the ghetto, she decided to return to Krakow. Here she met the remaining comrades who decided that she should travel to nearby Bochnia, where several of their colleagues were hiding in a bunker. There she would find Hillel Wodzislawski, who had undertken to lead the group after the murder of Dolek Liebeskind and the imprisonment of Laban and Shimshon Draenger. Thinking such an option still possible, the comrades decided to raise money to ransom Laban and the Draengers. For this purpose Schüpper returned to Warsaw, succeeded in entering the ghetto and announced the comrades’ decision to ransom the three prisoners. She succeeded in raising thirty thousand złotys. Once again mingling with the workers leaving the ghetto for the night shift, she was caught by a German guard renowned for his cruelty. Once more she was detained at the police station, this time appearing before the Polish and German police. She managed to stuff the money quickly into the pocket of a Jewish boy who entered to sweep her cell. Once again her courage and aplomb served her as she insisted she was Polish.

This time she decided to escape, taking advantage of the permission she received to relieve herself near the ghetto wall with only one German police officer to guard her. Seizing an opportune moment, she ran off. A hail of bullets followed her, one hitting her foot. Reaching a dark place, she hid in some ruins, emerging to enter the ghetto in the morning when movement resumed.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

As her wound began to heal, Schüpper joined the preparations for the great uprising. She celebrated the A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder of 1943 with her comrades in Warsaw, intending to return to Krakow afterwards. But she never did. The Germans surrounded the ghetto in order to kill the fifty-thousand survivors of the original Jewish population of 450,000 who refused to obey the command to leave. The battle began. A close friend of Schüpper’s, who asked her to watch over his mother while he went out to fight, brought both the women to the large bunker at 18 Mila Street, which members of the underworld had previously prepared and put at the disposal of the ZOB. There Schüpper met the organization’s commander, Mordechai Anielewicz (1919–1943), Zivia Lubetkin, and others.

Seven days later Anielewicz ordered Schüpper to accompany a group to the Aryan side, as she had successfully done before. “You will succeed this time too,” he told her. She was to meet Yitzhak Zuckerman (1915–1981), who was on the Aryan side. Lubetkin accompanied her to an additional meeting place from which they were supposed to enter the sewers, aided by a guide, and thus reach the outside. Schüpper succeeded in getting out, evading the German bullets fired at her as she emerged. When she met Zuckerman she reported everything that was going on in the ghetto and at 18 Mila Street.

On May 10, Zuckerman told Schüpper and her comrades of the fall of the bunker and the death of everyone in it when the Germans pumped in poison gas. Going from one place of refuge to another, Schüpper finally reached the Hotel Polski. Rumored to be a place of temporary refuge, it in fact became a trap for thousands of Jews: here the Germans gathered Jews who had foreign citizenship papers, supposedly to exchange them for German prisoners of war. But most of them were sent to Bergen-Belsen and from there to Auschwitz.

In August 1944 Schüpper too was sent to Bergen-Belsen. She and several of her comrades had believed they would be sent abroad. The Germans lied, promising them that they would be brought to a better camp and from there sent abroad. Schüpper stayed in Bergen-Belsen, where conditions were terrible: overcrowding, hunger, cold, lice and disease were rampant. At the end of 1944 Schüpper witnessed horrible acts of murder. The young women could hear the screams of the victims through the wall all week long. Miraculously, this time too Schüpper survived.

On March 8, 1945, all the inmates were ordered to the railway station, supposedly to be sent to Theresienstadt. Exhausted by hunger and disease, most could barely walk. The train finally stopped near Magdeburg, where the German officer in charge fled together with his men, leaving the prisoners inside the train to be liberated by American soldiers.

With the end of the war and victory over Germany, Schüpper found it hard to rejoice. Alone and helpless, her family and comrades dead, with no apparent reason to go on living, she could no longer hold back her tears. Psychologically incapable of participating in acts of revenge, she felt that all she could do was go on living to tell the story “of what happened to us during the years of the occupation, of the murder of millions, of life in the ghettos, of the unequal, impossible and heroic struggle against the Nazi beast and the hope that I would participate in building The Land of IsraelErez Israel.”

After the War

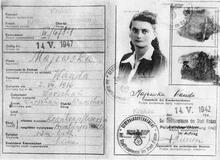

Arriving in Palestine in September 1945, Schüpper joined her comrades on A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.Kibbutz Beit Yehoshua where she met Aryeh Rufeisen (b. 1923) and they were married in 1947. In 1949 they moved to Bustan ha-Galil in the western Galilee, where they built their home and ran a farm. They had three children: Eliyahu (b. 1948), Yossi (b. 1952), and Ami (b. 1961).

Schüpper, who was always ready to give talks about her experiences in schools and various institutions, published an account of them in Farewell to Mila 18.

Schüpper passed away on April 23, 2017, at the age of 96.

Dawidson, Gusta. Justina’s Diary. Tel Aviv: 1978.

Rufeisen-Schüpper, Hela. Farewell to Mila 18: A Courier’s Story. Tel Aviv: 1990.

Gutman, Israel. The Jews of Warsaw 1939–1943: Ghetto, Underground, Revolt. Jerusalem: Hebrew University, 1977.

Peled, Yael (Margolin). Jewish Cracow 1939–1943: Resistance, Underground, Struggle. Tel Aviv: Bet Lokhame ha-Geta’ot, 1993.