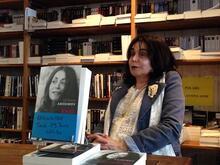

Mala Zimetbaum

Mala Zimetbaum was born in Brzesko, Poland, in 1918 and was captured and sent to Auschwitz at age 24. She became a privileged prisoner due to her fluency in several languages, thus gaining a relative freedom of movement. Zimetbaum and her lover, Edek, fled Birkenau and were captured by a border patrol twelve days later. Following torture and interrogation, she was sent to Birkenau and soon died. Multiple survivors noted that Zimetbaum had an unbroken spirit and did everything in her power to save others and fight back against the Germans. Her story has transcended the realm of individual experience and found a place in the chronicles of Aushwitz-Birkenau.

Mala got hold of a razor blade and quietly slit open her veins. … One of the blockführers grabbed her by the hair. Mala slapped him across the face with her bleeding hand. The SS man crushed her hand. Legend has it that she told him: “I shall die a heroine, but you shall die like a dog!” (Raya Kagan, Hell’s Office Women)

Mala Zimetbaum, the first woman and the first Jewish woman to escape from Auschwitz-Birkenau, was born on January 26, 1918, in Brzesko, Poland, the fifth and youngest daughter of Pinhas and Chaya Zimetbaum. In 1928, when she was ten years old, her family emigrated from Poland to Belgium, where they settled in Antwerp. Mala, a brilliant student, had to leave school because of the family’s economic situation—her father became blind—and work in a diamond factory.

Imprisonment

Probably on July 22, 1942, Mala was captured during one of the German efforts to hunt down Jews and was sent to Auschwitz on September 15. Her transport arrived in the camp two days later. Of the 1,048 Jews who arrived in the camp, two hundred thirty men and one hundred one women actually entered it after the selection. Mala was given the number 19880.

Thanks to her fluency in several languages (Flemish, French, German, English, and Polish), Mala was chosen to serve as runner and translator for the SS, and so became a privileged prisoner with relative freedom of movement.

While in the camp, Mala met Edward (Edek) Galinski, and the two fell in love. Edek, born on October 5, 1923, was brought to Auschwitz as a Polish political prisoner. He arrived in the camp on June 14, 1940, in the first transport of Polish prisoners from the Tarnow prison, and bore the number 531.

Many autobiographies and testimonies refer to Mala’s story as a collective story of sorts. Her figure has become a “local legend,” and her story has transcended the realm of individual experience and has found a place in the chronicles of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

One of Mala’s outstanding characteristics, which women survivors who knew her recount time and again, was that camp life did not corrupt her character. Unlike other privileged prisoners, Mala did all in her power to help other prisoners and saved many of their lives. The autobiographies and accounts that mention her recall that she was generous, risking her life for other prisoners, and standing proudly against the Germans. Also, many accounts tell that Mala was part of the camp’s underground. As Giza Weisblum relates:

One of Mala’s responsibilities was to assign the sick released from the hospital to various work details. She always tried to send the women who were still weak from their illnesses to the lightest type of work. Also, she always warned the patients of the coming selections, urging them to leave the hospital as quickly as possible. In this way, she saved the lives of many women.

Tzipora Silberstein recounts:

I would like Mala Zimetbaum’s story to be heard. … Mala’s story is not my story, but it is connected with me and many other people. … The young woman was pretty, indeed very beautiful. She spoke Polish, Yiddish, Flemish, French and German. She was charming. … This young woman did hundreds and thousands of good things for all of us. There were transports from Greece and she would stand near the Germans, writing things down. Many times, I heard that she only pretended to write, thus saving many people’s lives. She would bring medicine to sick people.

Escape and Death

On Saturday, June 24, 1944, Mala and Edek fled from Birkenau. Edek donned an SS uniform obtained from Edward Lubusch, an extraordinary SS man who aided prisoners, and Mala, who managed to obtain a blank SS pass, dressed as a prisoner being led to work. On July 6, the two were captured by a border patrol in the Beskid Zywiecki mountains at the Slovakia border, returned to the camp, and placed in separated cells in Bloc 11. Following a lengthy interrogation and severe torture, under which they did not break, and probably after confirmation by Himmler, they were transferred to Birkenau on September 15, 1944, for public executions which were to take place simultaneously: Mala’s in the women’s camp and Edek’s in the men’s camp. As her sentence was read, Mala slit her wrists and slapped SS man Ruitters, who attempted to stop her. She was taken to the camp hospital in order to stop the bleeding. According to some eyewitness accounts, she died on the way to the crematorium. According to others, she was shot to death at the crematorium entrance.

When Edek attempted to kick away the bench he stood upon, the SS men present held him back. After his sentence was read, Edek managed to shout: “Long live Poland!” before the noose tightened around his neck.

Legacy

There are various versions of Mala’s last words. Even now, despite the differences between the various versions, all the testimonies and autobiographies are united in their description of Mala, a courageous and impressive Jewish woman. She remained unbowed by camp life and will be remembered as one of the heroes who lived and died in Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Cyra, Adam. “The Romeo and Juliet from Birkenau.” In Pro Memoria (5–6), Information Bulletin of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and the Memorial Foundation for the Commemoration of the Victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camp. Poland: 1987, 25–28.

Maurice, Jack. “The Angel of Auschwitz: Mala Zimetbaum.” Jerusalem Post, 1972.

Sichelschmidt, Lorenz. Mala: Ein Leben und eine Liebe in Auschwitz. Bremen: Donat, 1995.

Weisblum, Giza. “The Escape and Death of the Runner Mala Zimetbaum.” In They Fought Back. The Story of the Jewish Resistance in Nazi Europe. Edited by Yuri Suhl. London: Schocken, 1967, 207.

Hebrew

Baumel-Theodor, Yehudit. “She Girds Her Loins with Courage: Heroines of the Holocaust in Collective Memory.” In Research of the Holocaust Period 13 (1996), Haifa: 189–201.

Gutman, Israel, et al. People and Ash: A Book of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim, 1957, 141–143.

Mark, Bernard. The Scrolls of Auschwitz (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Am ‘Oved, 1985.

Testimonies (Hebrew)

Bender, Baila. Yad Vashem Archives 1469:1. Bialystok: November 11, 1945.

Kagan, Raya. Declaration to the Israel Police. Yad Vashem Archives: May 29, 1961, 6.

Kagan, Raya. Testimony at the trial of Adolf Eichmann, vol. 2. Jerusalem: 1974, 1200.

Lokmo, Yona. Yad Vashem Archives 03/8971. Jerusalem: 1995.

Lonhoff, Karla. Yad Vashem Archives 03/4219. Jerusalem: 1981.

Olvesky-Zalmanovitz, Rahel. Yad Vashem Archives 03/4444. Jerusalem: May 21, 1984, 18.

Silberstein, Tzipora. Yad Vashem Archives 03/5467. Jerusalem: May 21, 1989, 1–23.

Solomon, Alexander. Yad Vashem Archives 03/3331. Jerusalem: 1970.

Weiss, Joseph. Yad Vashem Archives 03/6388. Jerusalem: 1991.

Selected Autobiographies

Fenelon, Fania. Playing for Time. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1997.

Levi, Primo. The Drowned and the Saved. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

Kagan, Raya. Hell’s Office Women: Oswiecim Chronicle. Merhavyah, Israel: Sifriat Poalim, 1947.

Nomberg-Przytyk, Sara. Auschwitz: True Tales from a Grotesque Land. Translated by Roslyn Hirsch. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Caroline Press, 1985.

Tedeschi, Giuliana. Questo povero corpo. Milan: Edizioni dell’Orso, 1946 (Hebrew edition: Yesh makom al pnei ha-adamah. Yad Vashem: 2000).

Wiesla, Kielar. Anus Mundi: Fifteen Hundred Days in Auschwitz-Birkenau (German). Translated by Susanne Flatauer. New York: Times Books, 1980, 224–263.

Fiction

Govrin, Michal. Hashem (Hebrew). Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1995.

Artifacts

Locks of Mala’s and Edek’s hair are on display at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum, along with a pencil portrait of Mala done by Zofia Stepien-Bator at Edek’s request.

Edek’s engraving of his and Mala’s names in the prison cell of Block 11.

Photographs of Mala before the war are extant, as are photographs of Edek during his imprisonment in the camp.

Yad Vashem has a scholarship fund in Mala’s name.