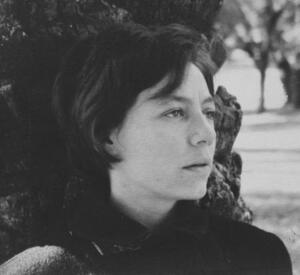

Alejandra Pizarnik

Alejandra Pizarnik stands out as one of the most important and influential figures in twentieth-century Latin American poetry. Pizarnik spent her childhood in the Avellaneda, in the province of Buenos Aires. At the age of nineteen, she published her first book, La tierra más ajena (The Most Foreign Country). During a four-year stay in Paris, she became acquainted with key literary figures and wrote some of her most accomplished works, although she also suffered from debilitating bouts of depression that pushed her to addictions of all kinds. In 1972, Pizarnik died after ingesting a large dose of sleeping pills. During her short life, she created a vast body of work, including several books of poetry, countless prose works, articles and essays, a play, and over 1000 pages of diaries.

Family and Early Life

Alejandra Pizarnik was one of the most important and influential figures in twentieth-century Latin American poetry. She was born Flora Pizarnik on April 29, 1936, to Elías and Rosa Pozharnik, Jewish immigrants to Argentina from Eastern Europe. Her father was a cuentenik, or peddler, selling goods, mostly jewels, from door to door; her mother was a housewife. Pizarnik had an older sister, Myriam, born in 1934.

Pizarnik spent her childhood in Avellaneda, a city in Buenos Aires province. While she had stable family life, from a young age she felt different from her family and community. She struggled with weight and speech issues and had a complicated relationship with her parents. In her diaries, she recalled those early years as a sad and lonely time: “My childhood is a burlap bag, emptied of coal, in which there are broken toys I do not remember” (November 6, 1962; all translations are by the author).

Pizarnik’s transition from child to adult was marked by three fundamental transformations. The first was changing her name: from the birth-given Flora to the self-chosen Alejandra, perhaps symbolizing a will to construct a new identity. The second was a change of scenery: in 1954, she began her studies at the University of Buenos Aires. Although she never graduated from any of the educational programs she pursued, this period proved crucial to her intellectual and artistic formation. Finally, and most importantly, was her transformation from a student with literary aspirations into a published poet: at the age of nineteen, Pizarnik published her first book of poetry, La tierra más ajena (The Most Foreign Country, 1955). The following years saw the appearance of La última inocencia (The Last Innocence, 1956) and Las aventuras perdidas (The Lost Adventures, 1958).

Paris

In 1960, Pizarnik fulfilled her long-time dream and traveled to Paris. During her four-year stay in the city, she became acquainted with prominent literary figures and wrote some of her most renowned works: Árbol de Diana (Diana’s Tree, 1962), Los trabajos y las noches (Works and Nights, 1965), Extracción de la piedra de locura (Extracting the Stone of Madness, 1968), and La condesa sangrienta (The Bloody Countess, 1971).

According to the recollections of family, friends, and the poet herself, her time in Paris constituted the happiest period of Pizarnik’s short life. Nevertheless, these years of freedom and creativity were also filled with terrible bouts of depression that pushed her to addictions of all kinds. Pizarnik was painfully conscious of her disease: “Recognizing my addictive nature: I must live inebriated. If not from alcohol let it be from tea, coffee, phosphoric acid, very strong tobacco … only after having drunk ten cups of coffee and swallowed various ‘cerebral revitalizing’ pills I can breathe freely, wander the streets without feeling the imperious desire to kill myself” (August 12, 1962).

Recognition and Tragedy

The years following Pizarnik’s return to Buenos Aires offered an unusual combination of auspicious events and tragic occurrences. On the one hand, she secured her position as an outstanding poet renowned in the Americas and Europe, as attested by the Guggenheim Fellowship and the Fulbright Scholarship she received in 1968 and 1971 respectively. On the other hand, she suffered from a series of emotional crises that drove her further toward alcohol and pills. The sudden death of her father in 1967 aggravated her already precarious condition. Pizarnik’s last years were characterized by a gradual withdrawal from her family and social life, a series of suicide attempts, and consequent hospitalizations. The last book published during her lifetime was El infierno musical (A Musical Hell, 1971). On September 25, 1972, at the age of 36, Alejandra Pizarnik died after ingesting a large dose of sleeping pills.

Alejandra Pizarnik lived a short yet prolific life. Five decades after her death, the full extent of her artistic legacy has become clear: more than eight books of poetry, countless prose works, articles and essays, a play, over 1,000 pages of diaries, and a lengthy correspondence, all of which were edited into a series of comprehensive volumes.

Representative Works

Two texts written at approximately the same time are representative of Pizarnik’s work: Extracting the Stone of Madness and the diaries of 1962.

“My profession (I also practice it in dreams) is to conjure and exorcise,” Pizarnik wrote in Extracting the Stone of Madness. Metaphorically speaking, any work of fiction or poetry is a continuous conjuring of events, places, and images in the minds of its readers. However, when the lyrical subject of La extracción speaks of her profession, she means it in the most literal sense. In this regard, it is possible to read the poems that comprise the book, and perhaps even the entirety of Pizarnik’s work, as a ritual consisting of an endless invocation and expulsion of spirits and cursed beings. In a gushing stream of poetic prose that reaches its peak in the fourth and last section of the book, the speaker summons ghostly figures, headless dolls, animals without bones or skin that wander a forest in ashes, gardens with broken statues beneath the moonlight, a woman dragging her own corpse, and more. One of the most accomplished poems of La extracción is “Las promesas de la música” (The promises of music):

Behind a white wall the variety of the rainbow. The doll inside her cage is bringing forth the autumn. It is the awakening of the offerings. A garden newly made, a cry behind the music. And may it sound forever, so that no one would attend the movement of birth, the mime of the offerings, the words of she who is me, tied to this silent one who is also me. And may nothing remain of me save the happiness of one who asked and was granted entry. It is the music, it is death, what I wanted to say at nights as diverse as the colors of the forest.

Pizarnik’s works tend to defy traditional categorization: while much of her poetry is written in prose (as in Extracting the Stone of Madness), her fiction frequently displays poetic qualities. That is also the case with her diaries, written continuously between 1954 and 1971. Pizarnik treated her diaries in the same manner as her prose and poetry, meticulously editing and rewriting them over the years. She even published a few excerpts in literary magazines. In this sense, we can certainly read the diaries both as autobiographical documents and as works of literature. Of particular interest are the diaries of 1962. They contain a series of poetic fragments that establish a clear textual dialogue with several of the short poems included in the cycle “Caminos del espejo” (“Roads of the mirror”), from the third part of Extracting the Stone of Madness (compare poems I, II, III, and XII with the diary entries dated July to December 1962). The poetry and the diaries are two realizations of the same artistic endeavor: that of endless conjuring and exorcism.

The second poem of “Roads of the mirror” can be compared to an excerpt from the diaries. The poem reads: “But I want to look at you until your face will move away from my fear like a bird from the sharp edge of the night.”

And the diary entry from August 10, 1962, reads:

But I remember you. Here I remember you. Hugging my memory. Looking at me behind my gaze. I dare not love you. Fear of annoying you. That is why I do not commit suicide. Fear of your anger. You tell me that you do not exist, that you are my old loved ghost who reincarnated in you. To another the metaphysical problems. I want to hug you savagely. Kiss you until you will move away from my fear like a bird that moves away from the sharp edge of the night. But, how to tell you this? My silence is my mask. My pain is that of a boy in the night. I sing and I fear. I love you and I fear and I will never tell you this with my true voice, this slow and deep and sad voice. That is why I write to you in a language you do not know. You will never read me and you will never know of my love.

Relationship to Judaism

On the one hand, Pizarnik grew up in a Jewish environment and was sent to a Jewish Schule (school), where she learned the history and religion of her ancestors; for a short time, she even participated in a Zionist youth movement. On the other hand, she lived a secular life largely detached from the Jewish community’s rites and holidays. Elements of Judaism are almost completely absent from her prose and poetry. In her diaries, she repeatedly refers to her Jewish identity, but these reflections are often contradicting and ambiguous. See for instance the fragment from October 10, 1968: “I am a very strange Jew. I take pride in the Hassidim as if they were my sons and at the same time I do not like Martin Buber, going to Israel, nor do I like Yahweh, so similar to that old lion in the zoo.”

During her lifetime, Pizarnik never reached the Promised Land; she never traveled to Israel, and she never truly found her place in the world. However, in the years and decades following her death, readers in Israel became increasingly acquainted with her writing through translations, studies, and commemorative events. Surely, future publications of Alejandra Pizarnik’s work in Hebrew and other languages will enhance the familiarity of readers around the world with this remarkable writer.

Selected Works by Alejandra Pizarnik:

Spanish

Poesía completa. Barcelona: Lumen, 2000.

Prosa completa. Barcelona: Lumen, 2002.

Diarios. Barcelona: Lumen, 2013.

Nueva correspondencia (1955-1972). Barcelona: Lumen, 2017.

English

From the Forbidden Garden: Letters from Alejandra Pizarnik to Antonio Beneyto. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University Press, 2003.

Diana’s Tree. Translated by Yvette Siegert. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2014.

Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972. Translated by Yvette Siegert. New York: New Directions, 2016.

The Most Foreign Country. Translated by Yvette Siegert. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2017.

The Last Innocence/The Lost Adventures. Translated by Cecilia Rossi. New York: Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019.

Chatellus, Adélaïde de, and Milagros Ezquerro, eds. Alejandra Pizarnik: The Place Where Everything Happens (Spanish). Paris: L’Harmattan, 2013.

Goldberg, Florinda F. Alejandra Pizarnik: “This Space We Are” (Spanish). Gaithersburg, MD: Hispamérica, 1994.

Graziano, Frank, ed. Alejandra Pizarnik: A Profile. Durango, CO: Logbridge-Rhodes, 1987.

Mackintosh, Fiona J., and Karl Posso, eds. Árbol de Alejandra: Pizarnik Reassessed. Woodbridge, UK: Tamesis, 2007.

Piña, Cristina. Alejandra Pizarnik (Spanish). Buenos Aires: Planeta, 1991.0