Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman

Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman learned folk songs from her mother and a love for Yiddish from her father. After a lifetime of writing poetry, stories, folklore, songs and children's literature in the language of her childhood, she remains a force on the Yiddish educational scene.

Courtesy of Linda Lipsky

Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman grew up in Romania in a family of Yiddish linguists and writers, but soon after marrying Dr. Jonah Gottesman in 1941, she and her family were detained in a ghetto. They eventually returned to Vienna, where Schaechter-Gottesman worked with the Freeland League (the League for Yiddish). In 1950 she immigrated to America, where she mentored young poets, edited Yedies fun YIVO and Afn Shvel, and was secretary of the Yiddish PEN club. She began writing in 1956, starting with Khayml un taybele, a children’s book, and balanced books and music for children with poetry for adults, including Perpl shlenglt zikh der veg (2002), which combined poetry with visual art. Schaechter-Gottesman’s honors include the National Endowment for the Arts’ National Heritage Award (2005).

Introduction

Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman was born in Vienna on August 7, 1920, and died in the Bronx, New York, in 2013. A Yiddish poet, songwriter, educator, writer of children’s literature, graphic artist, folklorist, song stylist, Yiddish territorialist and community activist, Schaechter-Gottesman was inducted into the Museum of the City of New York’s “City Lore Hall of Fame” in 1999, an award that honors “grass roots contributions to New York’s cultural life.” Winner of the Usher Tshutshinsky Prize of the World Congress for Jewish Culture in 1994, she was something of a folk hero among her faithful. Her volume of songs, Zumerteg (Summer Days), is a vade mecum for lovers of Yiddish. The plaintive yet uplifting meditation on deferred dreams, “Harbstlied” (Autumn Song, 22), has been sung in Berlin, Tel Aviv, Buenos Aires, and Odessa by Schaechter-Gottesman herself and by noted performers such as Michael Alpert and Nehama Liphshitz.

Early Life and Family

Schaechter-Gottesman learned folksong from her mother; her father educated her to the love of Yiddish. She grew up in Czernowitz (then Cernauti, Romania, today Chernivtsi, Ukraine), in the province of Bukovina known as the “El Dorado of the Jews,” the seat of linguistic diversity by token of its changing borders and colonizing forces. Her father, Binyumin Schaechter, born in 1890 in Dilyatyn, Galicia, then part of the Austro-Hungarian commonwealth, moved to Vienna in 1918, where he married Lifshe Gottesman the following year. He was a descendent of generations of shohtim (ritual slaughterers) and Horodenker Hasidim (Vegn Mordkhe Schaechter 7). By profession a journalist, he also helped his wife in their dry goods business. A devotee of Chaim Zhitlovsky, the young Binyumin attended the First Yiddish Language Conference in Czernowitz in 1908. This was to become the defining moment in the history of Yiddish, as indeed it would become for the Schaechter family and its successive generations of linguists, scholars, musicians, and journalists. Schaechter-Gottesman’s brother, Dr. Mordkhe Schaechter (192-2007), pre-eminent linguist and key figure in Yiddish language planning, was an adaptive terminologist and dialectologist. He was the prime mover in efforts to standardize, normalize, and modernize the Yiddish language and its orthography. In her poem, “Er hot gehat di skhie” (He Had the Honor) (Perpl 120–121), Schaechter-Gottesman writes about the passion which brought her father to hear the fierce polemic of the literati and linguistic ideologues of his generation—Isaac Leib Peretz (1852–1915), Sholem Asch (1880–1957), Matthias Mieses (1885–1945), and Nathan Birnbaum (1864–1937), among others—who gathered to determine the fate of Yiddish as “a national language.” As she tells it, her father, a young yeshiva graduate, went to Czernowitz as if on “pilgrimage” to a holy site. In what Schaechter-Gottesman’s mother would call in her memoirs “[t]he [f]irst [a]ct” in the family’s wartime tragedy, Durkhgelebt a velt (A Full Life, 248), Binyumin was arrested by the Russian military on September 14, 1940, beaten, imprisoned after a trial on trumped-up charges, and finally driven into Siberian exile from which he never returned.

The Durkhgelebt a velt Memoirs

In her memoirs, Lifshe Schaechter-Widman (1893–1973) recorded in lively prose details of the family’s life in her birthplace, Zvinyace (Ukraine), and in Vienna, Czernowitz, Bucharest, and finally New York. The memoirs are a “rare and dependable reflection of east Galicianer and northern Bukoviner Yiddish of the late nineteenth century” (“Editorial Note” to Durkhgelebt 5). Schaechter-Gottesman remembers typing this archive of which she became custodian: “Now I’m mother to your past …”(“S’letste bletl” [The Last Page], Sharey 42). Lifshe sang ballads and theater songs that were produced as field recordings in 1954 and issued in 1986 as a cassette entitled Az di furst avek (When You Leave).

From Lifshe’s memoirs one learns that “Beyltzye” (a regional endearment) was a frail and pallid child who more than made up for her physical weakness with her spirited, though timid, nature. She sang beautifully and knew her compatriot Eliezer Shteynbarg’s songs and mesholim (fables) by heart. The young Beyle was taken to plays and recitations and would mimic the speeches and ape the gestures of, for example, the itinerant stars of the Vilna Troupe.

World War II and Immigration to New York

She married her cousin, Jonah Gottesman (1914–1996), a medical doctor, on February 1, 1941. No sooner had they moved to Zvinyace than they had to flee the German terror. But for serendipity and the acts of sacrifice of a Jewish family in Karolyuvka, in eastern Galicia, they would have followed the inevitable trajectory of the Bukovina Jews: deportation to Transnistria (region in W. Ukraine between the Bug River in the east and the Dniester River in the west) to almost certain death. The Schaechter and Gottesman families were further saved by Jonah’s medical credentials; they remained in Bucharest for two years. Without Mordkhe, who was arrested in transit, they stole across the border to Vienna, where Jonah became the doctor-in-chief of the DP camps.

In Vienna Schaechter-Gottesman was associated with the Freeland League from 1947 until 1950, when she and Jonah emigrated to New York, where she kept up her Yiddish activism. She continued her association with the Freeland League until 1979. She remained active in its successor, the League for Yiddish, and in the Sholem Aleichem Cultural Centre and the Congress for Jewish Culture. She mentored a generation of young poets, including Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath and Elinor Robinson, and edited the anthology Vidervuks (Regrowth) which grew out of her Yugntruf (Youth for Yiddish) writer’s circle. She served as literary editor of Yedies fun YIVO and Afn Shvel and was secretary of the Yiddish PEN club.

Yiddish Education and Literary Works

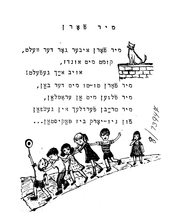

Schaechter-Gottesman studied at the Jewish Teachers Seminary in New York and became a force on the Yiddish educational scene, teaching at the Workmen’s Circle and the Sholem Aleichem Folkshul until its closure in the 1970s. She edited the children’s journal written by children, Enge-Benge, and published juvenilia in Kinder Tsaytung and Pedagogisher Buleten. Like many women writers, including Kadya Molodowsky and Ida Maze, Schaechter-Gottesman began her literary career with the publication of children’s literature: Khayml un taybele (1956) and Mir forn (We’re Off, 1963). The title song of her book of children’s songs Fli mayn flishlang (Fly, My Kite, 1999) urges the child to imitate the kite’s fearless, though tethered, upward aspiration. In the book Mume Blume di makhsheyfe (Aunt Bluma the Witch, 2000), Schaechter-Gottesman creates a whimsical universe with its own laws and fantastical creatures. A number of her animal songs are included on the CD Di grine katshke (The Green Duck).

Schaechter-Gottesman studied art in Vienna (1936–1938) and in Bucharest (1945–1946). Her poetry is read most fruitfully in the light of her abiding interest and achievement in the graphic arts: “I started drawing and painting from early childhood and considered it my calling. Poetry came later (“My Writing,” personal correspondence). Her works, which have been widely exhibited, range from charcoal gestural sketches which accompany her poems, through opaque aquarelles of nature and the city, to lyrical oil portraits. Perpl contains a cycle of ekphrastic poems which describe the paintings’ textures, lines, spaces and aspects of representation or abstraction. Sharey contains the haunting visual image of the “black on white” of her father on the snowy plains of Siberia.

Critical Acclaim and Yiddish Linguistic Legacy

Schaechter-Gottesman published poems, stories, and reviews in a number of journals, including Afn Shvel, Goldene Keit, Der Veker, and Cheshbn. Her debut collection of 1972, Steshkes tsvishn moyern (Footpaths amid Stone Walls) met with critical acclaim for its unique voice and thematic daring. Simkhe Lev hailed Schaechter-Gottesman’s presence among women writers, such as Asya and Rivka Basman (34). While implicitly acknowledging the double marginalization that is the lot of the Yiddish woman writer, Schaechter-Gottesman does not call political attention to her gender. Chava Rosenfarb’s musings on this matter seem fitting: “… feminist thinking has not managed to penetrate to the core of my basic literary interests…[M]y wavering attitude towards feminism was … rooted in the specificity of my being a Yiddish woman writer” (217). Yet Schaechter-Gottesman’s religious typology is a female one, including the image of her grandmother at her prayers of supplication (“Mayn bobe’s tkhine,” Perpl 19) and the sight of pious women in white kerchiefs. In the Yiddish tradition of the ethical will, beginning with the seventeenth century memoirs of Glückl of Hameln, Schaechter-Gottesman issues a moral imperative, a living testament to her children. Her daughter Taube (b. 1950), her late son Hyam (1953–1997), and her son Itzik (b. 1957), co-editor of the newspaper Der Forverts, folklorist and passionate Yiddishist, are urged not to squander their linguistic legacy.

The collection Sharey appeared in 1980. Among its poems are “occasional” verses, both political (on the killing fields of Cambodia, 76) and personal (subtitled, “On reading a Soviet brochure on the Bukovina,” 77). Occasional, too, is a cycle of poems reflexive of the poetic process, including “Bergelsonishe struktur” (Bergelson’s Structure, 12). This autotelic concern with the poem’s own devices positions her squarely in the varied tradition of Yiddish Modernism. Her poetry is rife with allusion and intertextual references to Modernism’s human monuments: Moshe Leib Halpern (1886–1932), Jacob Glatstein (1896–1971), and David Bergelson (1884–1952) among others. She uses their themes and lexicon, both in parody (“Kurts—Moishe Leyb” [For Short—Moshe Leyb], Perpl 64) and in tribute (“Esther” [Esther Shumiatcher], Steshkes 80). Schaechter-Gottesman’s aesthetic reveals both her erudition and her affiliation: “I think of myself as post-Inzikhist and partly experimental. … I admire the cleverness and wit of Yankev [Jacob] Glatstein and the bold expressionist lines of M. L. Halpern” (“My Writing,” personal correspondence).

Zumerteg (Summer Days) appeared in 1990, followed by a cassette and later a CD of the same name. “A rege” (A Moment), published earlier as a poem in Steshkes, presents the interpenetration of real time and eternity: “Eternal is the moment” (28). Schaechter-Gottesman’s most recent CD, Af di gasn fun der shtot (On the Streets of the City), reveals her contemporary concerns. “The Ballad of September 11” is written in the folk tradition of disaster commemoration. As threnodist, she laments the funeral pyre of history: “And it smolders still, smolders without end …” (Liner Notes 8–9). As an international troubadour, Schaechter-Gottesman lends her own improvisational and melismatic style to her concert renditions.

Later Writings

Schaechter-Gottesman’s Perpl shlenglt zikh der veg (2002) contains poems whose music is attuned to the cadence of the rain (“Not Merely the Rain,” 25) and to the unbearable beauty of the violin’s strains (“Fiddle,” 34). Boris Sandler holds that with this third collection Schaechter-Gottesman located herself both within and against the tradition as represented by Ezra Korman’s landmark 1928 anthology of Yiddish women poets.

Finally, neither the inward turn of the Inzikhistn nor the tortured lyric assertions of the Expressionists afford her definitive answers to the questions posed throughout her canon, most notably “Tsu vos?” (To what end?) (“Bloiz linies” [Only Lines], Perpl 68). The resolution, if not the answer, might lie in a recurrent word in Schaechter-Gottesman’s lexicon: “elehey” (as if). One has to imagine life “comme si” (as if) it had meaning. If our fathers and our sons are taken from us prematurely and cruelly, let us do good in their names. If our daughter’s gait is slowed by a capricious fate, let us live as if fortune’s wheel might turn ever so slightly in her favor. If the bloom of Yiddish has been blighted in the Holocaust, let us tend its garden every day with able hands and a sense of mission. Hence she embraces the world with all its evasions, uncertainties and anguish, as in the poem, “Maskim” (Agreed): “I agree with the world/I agree with the sun/I agree with the wind” (Steshkes 52). Her muse, by her own admission, is exacting, irascible, “blood-sapping” and relentless (“My Muse,” Steshkes 21). Schaechter-Gottesman’s muse inspired her to hitherto unimagined metaphors.

In 2005 Schaechter-Gottesman won the National Heritage Award given by the National Endowment for the Arts.

"Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman: Song of Autumn," a 72-minute film by Josh Waletsky, was released in 2007 as part of the League for Yiddish's Series "Worlds Within a World: Conversations with Yiddish Writers." A new collection of Schaechter-Gottesman’s poetry, דער צוויט פֿון טעג ("Der tsvit fun teg," "The Blossom of Days") was released in the autumn of 2007.

Schaechter-Gottesman died on November 28, 2013, in the Bronx at the age of 93.

Selected Works of Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman

Khayml un taybele (Khayml and Taybele). New York: 1956.

Mir forn (We’re Off). New York: 1963.

Steshkes tsvishn moyern (Footpaths Amid Stone Walls). Tel Aviv: 1972.

Sharey (Dawn). New York: 1980.

Zumerteg: tsvontsik zinglider (Summer Days: Twenty Yiddish Songs). New York: 1990, second edition, 1995, CD.

Lider/Poems. Trans. Charne Schaechter et al. New York: 1995.

Fli mayn flishlang: kinderlider mit musik (Fly, My Kite: Children’s Songs with Music). Trans. Charne Schaechter. New York: 1999.

Mume Blume di makhsheyfe (Aunt Bluma the Witch). Illustrated by Adam Whiteman. Trans. Charne Schaechter. New York: 2000.

Perpl shlenglt zikh der veg: lider (The Winding Purple Road: Poems). New York: 2002.

Af di gasn fun der shtot (CD) (On The Streets of the City: Songs). New York: 2003. Also included in these anthologies: Voices Within the Ark: The Modern Jewish Poets, edited by Howard Schwartz and Anthony Rudolf. New York: 1980.

Di grine katshke (The Green Duck: A Menagerie of Yiddish Songs for Children, CD). New York: 1997.

Der tsvit fun teg: Lider un tseykhenungen/The Blossom of Days: Poems and Drawings. New York: 2007.

Glatstein, Jacob, A. Glants-Leyeles and N. Minkov. “Introspectivism: Manifesto of 1919.” In American Yiddish Poetry: A Bilingual Anthology, edited by Benjamin Harshav and Barbara Harshav, 774–784. Berkeley: 1986.

Goldsmith, Emanuel S. Di yidishe literatur in Amerike: 1870–2000 (Yiddish Literature in America 1870–2000), 2 vols. Vol. 2: H. Leivick to I. B. Singer. New York: 1999.

League for Yiddish editorial board, ed. Vegn Mordkhe Schechter un zayn verk (Mordkhe Schaechter and his Work). New York: 1987.

Lev, Simkhe. “Poets of 1972” (Yiddish). S’vive (September 1972): 34–36.

Rosenfarb, Chava. “Feminism and Yiddish Literature: A Personal Approach.” In Gender and Text in Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature, edited by Naomi Sokoloff, Anne Lapidus Lerner and Anita Norich, 217–226. New York: 1993.

Sandler, Boris. “A New Collection of Poems by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman” (Yiddish). Di Tsukunft (November 2002): 10–22.

Schaechter-Widman, Lifshe. Durkhgelebt a velt: zikhroynes (A Full Life: Memoirs). edited by Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman and Mordkhe Schaechter. New York: 1973.

Unattributed. “Schaechter-Gottesman, Beyle.” (Yiddish). In Leksikon fun der nayer yidisher literatur. Vol. 8, edited by Berl Kagan, Israel Knox and Elias Schulman, 771–772. New York: 1981.

Yungman, Moshe. “Lyrical Impressions” (Yiddish). Goldene Keit 78 (1973): 221–225.

Waletsky, Josh. Beyle Schaechter-Gottesman: song of autumn. Produced by Sheva Zucker. 2007; New York: League for Yiddish. Film.