Sarah Bernhardt

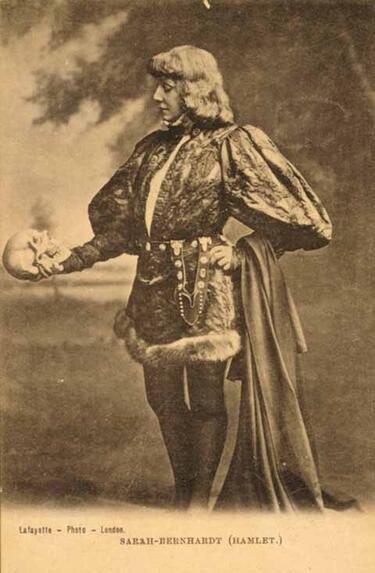

"Accused" of sounding "like a Jew," French actress Sarah Bernhardt (1844-1923) wrote, "I am a daughter of the great Jewish race, and my somewhat uncultivated language is the outcome of our enforced wanderings." Indeed, she took her own theater company around the world, transforming herself, a member of the wandering race, into an object of worldwide welcome and acclaim. The great French actress appears here in 1880.

Institution: U.S. Library of Congress.

Hailed as “the Divine Sarah,” Sarah Bernhardt is recognized as the first international stage star. She debuted in the title role of Racine’s Iphigénie in 1862 and built a reputation as a versatile actress with an expressive voice and poetic gestures. She was hailed for her performances in Racine’s Phèdre in 1874 and Victor Hugo’s Hernani in 1877. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, she pursued multiple careers, buying a series of French theaters to produce modern experimental plays while touring Europe, the United States, Latin America, and Canada. She also wrote, painted, and sculpted. During a 1905 performance in Rio de Janeiro, Bernhardt badly injured her knee, which finally required amputation in 1915. Despite her injury, Bernhardt performed on stage and in films until weeks before her death.

To be modern in poetry, to represent really oneself and one’s surroundings, the world as it is today, to be modern and yet poetical, is, perhaps, the most difficult, as it is certainly the most interesting, of all artistic achievements. In music the modern soul seems to have found expression in Wagner; in painting it may be said to have taken form and color in Manet, Degas and Whistler; in sculpture, has it not revealed itself in Rodin? On the stage it is certainly typified in Sarah Bernhardt (Stokes, 15, quotes from Symons).

The French actress Sarah Bernhardt, named by her fans the “Divine Sarah,” is recognized as the first international stage star. Bernhardt played some 70 roles in 125 productions in Europe, the United States, Canada, South America, Australia, and the Middle East. She managed several theaters in Paris before leasing the Théâtre des Nations, which was renamed Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt (today Théatre de la Ville). Bernhardt reinvented herself as a public icon, allowing the romances and tragedies of her stage heroines to reflect her own life. Her notable roles included the title characters in Phèdre by Jean Baptiste Racine (1639–1699), La Tosca by Victorien Sardou (1831–1908), Sardou’s Théodora, Adrienne Lecouvreur by Eugène Scribe (1791–1861), Doña Sol in Hernani by Victor Hugo (1802–1885), and Marguerite Gautier in La Dame aux camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils (1824–1895).

Family and Education

Sarah Bernhardt was born as Henriette Rosine Bernard to the Dutch Jewish courtesan Julie Bernard (?–1876, also referred to as Judith and as Youle in biographies), on October 23, 1844. Her original birth certificate is lost and some biographers also note the previous day as her birth date. Julie was the daughter of Maurice Bernard (also noted in documents as Bernardt), an oculist, and Jeannette née Hart (noted also as Hard, or van Hard). Sarah was the eldest of Julie’s three illegitimate daughters; the second was Jeanne (1851–1900) and the third was Régine (1853?–1874). It is not clear who was Sarah’s father. It is assumed that it was a young student named Morel who pursued a career as a naval officer. Her uncle Edouard Bernard signed as her father in her baptismal certificate when Bernhardt was thirteen. She spent her childhood in a pension, cared for by a hired nurse, and in Grandchamp Augustine convent school near Versailles. Her mother was absent most of the time. Given her religious education, she wanted to become a nun. Yet when she turned sixteen, her mother’s lover Charles Duc de Morny (1811–1865), the illegitimate half-brother of Napoleon III, designated for her a career in the theater.

Jewish Identity

For two years Bernhardt studied acting at the Conservatoire de Musique et Déclamation in Paris, where the acting style of another student, the famous Jewish actress Rachel, was regarded as the ideal. Throughout her career Bernhardt kept in her room a portrait of Rachel, with whom she would be compared time and again. Rachel became a celebrity in Paris and in London through her performances as Phèdre (1843) and in the title role in Scribe’s Adrienne Lecouvreur (1849). Choosing to adopt Sarah as her stage name, Bernhardt was aware that Rachel’s fame and her own future reputation would be linked to romantic and antisemitic fascination with Jewish women. Their identification as Jews drew discriminatory antisemitic caricatures, which attacked them, for example, for their presumed greediness. Their Jewishness was further stressed in antisemitic contemporary novels and pseudo-biographies, such as Dina Samuel (1882) by Félicien Champsaur (1858–1934), Les Mémoires de Sarah Barnum (1883) by Marie Colombier (1841–1910), La Faustin by Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896), and Le Tréteau by Jean Lorrain (1855–1906).

After the Franco-Prussian war (1871), Bernhardt was forced to defend herself against press accusations that she was German and Jewish. Her proud reaction, reported in her biographies, was: “Jewish most certainly, but German, no.” In his book on Bernhardt (1899), the journalist Jules Huret of Le Figaro quoted a letter she wrote in connection with these accusations, in which she parenthetically restated her Jewish identity: “If I have a foreign accent—which I much regret—it is cosmopolitan, but not Teutonic. I am a daughter of the great Jewish race, and my somewhat uncultivated language is the outcome of our enforced wanderings.” When Sarah Bernhardt attained fame and independence, she took her company around the world, turning the rejected (enforced) wanderer into an internationally admired and welcomed star.

Acting Style

In 1862 Bernhardt made her first appearance in the title role of Racine’s Iphigénie at the national theater, the Comédie Française. However, she was dismissed a few months later after slapping an older actress. Dissatisfied with the small parts she received in the fashionable theater Gymnase-Dramatique, she escaped to Brussels. On December 22, 1864, she gave birth to her only son Maurice, the fruit of her affair with Henri Prince de Ligne (1824–1871) in Brussels. In 1866 she began working at the Odéon. In 1868 she had her first public success playing the seductive Anna Damby in Alexandre Dumas’s Kean. The critics noted her eccentric costume and warm voice. That same year she played Cordelia in Shakespeare’s King Lear. Her greatest triumph at this theater was her travesti role (playing a male role) as the minstrel boy Zanetto courting an aging courtesan in the one-act play Le Passant by François Coppée (1842–1908) in 1869. During the Franco-Prussian War Bernhardt opened a hospital in the Odéon. When Victor Hugo returned from exile after the war, Bernhardt brilliantly played Queen Maria in his Ruy Blas at the theater. The audience was captivated by her gestures, expressive voice, and superb declamation. In 1872 her success convinced the Comédie Française to invite her back. In the succeeding years with the Comédie Française she attained full stature as a celebrity through her portrayals of Phèdre (1874) and of Doña Sol in Hugo’s Hernani (1877).

Bernhardt developed her own emotional romantic acting style based on her lyrical voice (known as the “golden voice”), calculated nervous action, and the subversion of her viewers’ expectations concerning her characters, disclosing strength in weakness and weakness in strength. Accordingly she impressively acted travesti roles such as Zanetto in Le Passant and later Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Yet as the author Elaine Aston has noted, the essence of Bernhardt’s performance was pictorial. She sculpted and drew with some success, exhibiting at the Salon at various times between 1876 and 1881. In 1880 she also exhibited a painting there. Yet her finest skill was projecting her emotional poses into unforgettable tableaux. She made sure that her appearance would echo masterpieces (for example, playing Théodora dressed similarly to the Empress Théodora in the mosaic murals in Ravenna), or would be marketed as such, through oil portraits, posters and photos of key scenes, as were her portrayals of Fédora and Marguerite Gautier in La Dame aux camélias. The famous photo by Melandri of Bernhardt, lying dressed in white with closed eyes in a coffin, echoing the painting of Ophelia by Sir John Evertt Millais (1829–1896) and La jeune martyre by Paul Delaroche (1797–1856), was meant to promote her favorite tableaux of dying heroines such as Marguerite, Fédora, and Adrienne falling lifeless into the arms of their lovers.

In 1876, Sarah’s mother died. That year, Bernhardt’s reputation as a femme fatale provoked a scandal when two journalists were challenged to duels by two gentlemen who wanted to defend her honor. During this time she also left her apartment in the rue de Rome and moved to her own newly built grand house at the corner of the rue Fortuny and the avenue de Villiers. Renowned painter friends such as Gustave Doré (1832–1883), Georges Clairin (1843–1919), Louise Abbéma (1853–1927), and Philippe Parrot (1831–1894) covered the walls of her house with allegorical murals. Her artistic bastion symbolized her new bohemian way of life. Unlike other famous salons in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, the central attraction in her salon was not her guests but the hostess herself. Among her friends were the authors George Sand (1804–1876) and Victor Hugo, artist Gustave Moreau (1826–1898), novelist Pierre Loti (1850–1923), and playwrights such as Jean Richepin (1849–1926) and Jules Lemaître (1853–1914), who also became her lovers.

Growing Fame

In June and July 1879, Bernhardt scored a triumphant debut at the Gaiety Theatre in London with the Comédie Française. Early in 1880 she resigned from the company and left Paris for a tour with her own company in Europe and in the United States. For the American tour Bernhardt chose plays that best showed her talents: Phèdre, Adrienne Lecouvreur, Hernani, Froufrou by Henri Meihlac (1831–1897) and Ludovic Halévy (1834–1908), and one in which she had not previously acted, Dumas fils’s La Dame aux camélias. Her tour was a great financial success.

Early in 1882 Sarah met Aristidis Damala (1857–1889), a Greek army officer who was her junior by twelve years. They married at St. Andrew’s in a Protestant ceremony in London at the end of Bernhardt’s successful tour through Italy, Greece, Hungary, Austria, Sweden, England, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Holland, and Russia. Treated as royalty, Sarah received honors from the highest nobility. King Umberto of Italy presented her with an exquisite Venetian fan, Alfonso XII of Spain gave her a diamond brooch. The Austrian emperor Franz Joseph placed an antique cameo necklace around her neck after her performance of Phèdre. In Saint Petersburg Tsar Alexander III was deeply moved by her art.

In July 1882, after her return to France, encouraged by the success of her company, she bought the Théâtre de l’Ambigu in the name of her son Maurice. This turned into her first managerial disaster, although accompanied by her triumph as a Boulevard actress. The playwright Victorien Sardou offered her melodramatic scenarios to display her abilities. With her consent he wrote plays such as Fédora (1882), Théodora (1884), and La Tosca (1887). As she received the highest payment for an actress, she gathered huge debts at her theater. Her son Maurice gave up the directorship of the Ambigu theater, and Bernhardt leased the Porte Saint-Martin, a large 1800-seat theater. Following the successful performance of Froufrou and La Dame aux camélias, Richepin’s new play for her, Nana Sahib, was a failure. She returned to La Dame aux camélias in order to save her theater from financial catastrophe. Her repertoire of assured successful roles suggests that her performances were experienced as “ritualized events.”

In September 1884 Bernhardt began her successful cooperation with Félix Duquesnel (1832–1915) as the new director of Porte Saint-Martin and Sardou as the house playwright. Their major sensation was the play Théodora, which opened on December 26, 1884. The play was performed 300 times in Paris and more than 100 times in London in 1885 and 1886. In 1886 she left for a tour through South and North America, starting with Brazil. In the summer of 1887, she returned to Paris and proudly boasted to friends that her tour made her a millionaire. Bernhardt bought a house at 56 Boulevard Péreire where she lived until her death. That same year, her son Maurice married the Princess Marie-Thérèse Jablonowska (? – 1910), a member of a distinguished Polish family. Bernhardt’s partnership with Duquesnel and Sardou achieved a further triumph with Sardou’s La Tosca. In 1889 her husband Damala died of a morphine overdose.

A few months after Bernhardt became the grandmother of Maurice’s daughter, Simone, she asked Duquesnel to direct her in a new play by Emile Moreau, Le Procès de Jeanne d’Arc. Through this portrayal of a nineteen-year-old virgin, the 45-year-old Bernhardt reclaimed her honor as an actress who had hitherto been identified with roles of a vicious queen, a prostitute, and a lady of doubtful morality. Although the play was a spectacle and a success, it closed after sixteen weeks because Bernhardt suffered physically from the need to constantly fall on her knees. The successful partnership was halted with the failure of Sardou’s Cléopâtre in 1890.

In 1891 Bernhardt embarked on a lucrative world tour. In June 1892 she was in London rehearsing Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, written especially for her in French. The rehearsals were interrupted because of Lord Chamberlain’s refusal to grant it performance license in England. A year later she sold the Porte Saint-Martin theater and through her agent arranged to buy the Théâtre de la Renaissance, a theater for small-scale productions and intimate soirées decorated in rococo style. Bernhardt returned to France from her world tour as the richest and most publicized actress of the day. Her net worth was 3.5 million francs d’or.

Her five years of directing every aspect of rehearsal in the Théâtre de la Renaissance were her most innovative years. Bernhardt was willing to experiment with plays by young writers such as Jules Lemaître (Les Rois, 1893) and Octave Mirbeau (1850–1917 [Les Mauvais Bergers, 1897]). Mirbeau’s treatment of the subject of striking factory workers provoked a scandal that forced her to close the theater temporarily. With La Princesse lointaine (1895) by Edmond Rostand (1868–1918), she aligned herself with contemporary symbolist theater. She failed, however, when she attempted to capitalize on the trend of mysticism and religiosity in the theater with Sardou’s Spiritisme and Rostand’s gospel play La Samaritaine (1897). In 1897, competing with the sensational season of Eleonora Duse (1858–1924) at her theater, Bernhardt arranged to present La Ville Morte (The Dead City) by Duse’s lover, Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863–1938), in the following year. However, the debts gathered at her theater amounted to two million francs d’or.

In January 1899, determined to avoid further financial losses, Bernhardt signed a 25-year lease for the Théâtre des Nations at Châtelet which was owned by the City of Paris. The theater offered production opportunities on a monumental scale, allowing her—at the age of 55—a safe distance from her audience. She renovated the theater in accordance with her status as a magnet star. The public foyer became her own “little Louvre,” exhibiting large panels by Abbéma, Clairin, Louis Bernard, and Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939), respectively depicting Bernhardt as La Samaritaine, Gismonda, Théodora, “La Tragédie antique,” La Dame aux camélias, Hamlet, La princesse lointaine, and L’Aiglon. The theater opened with a revival of La Tosca, continuing with a controversial performance of Bernhardt playing Hamlet. But the greatest triumph was achieved through her travesti role in Rostand’s L’Aiglon in March 1900. Dressed in a military uniform, she played the role of Napoleon’s seventeen-year-old son, the ill-fated Duc de Reichstadt (1811–1832). The production was timed to coincide with the great Paris Exposition, which lured large crowds to the city and encouraged French patriotic spirit. Sarah gave 250 consecutive performances of L’Aiglon, earning her respect as a national heroine. In 1903 a further success was achieved through Sardou’s seventh and last historical melodrama for Bernhardt, La Sorcière (The Sorceress), set in Toledo at the time of the Inquisition. Sarah played a passionate gypsy prosecuted by a villain. In 1904, she played Pelléas in a London production of Pelléas and Mélisande by Maurice Maeterlinck (1862–1949).

In 1905 Bernhardt left for a long tour in America. During her last performance in La Tosca in Rio de Janeiro she had an accident that eventually led to the amputation of her right leg a decade later. In March 1906 she performed in a huge tent seating 5000 in Kansas City, Missouri, and in Dallas and Waco, Texas. In 1906, after her return to Paris, she played Saint Theresa in the scandalous play La Vierge d’Avila (The Virgin of Avila) by Catulle Mendès (1841–1909). After a successful appearance in London with L’Aiglon, Bernhardt, now aged 66, again left for America in October 1910. Her chosen leading man for the tour was the handsome 27-year-old Lou Tellegan, who became her lover for the next three years. Bernhardt appeared in several silent films, but her only success was in the title role of Elizabeth Queen of England in 1912. After her return to Paris at the end of 1913 she performed the role of Sarah, the mother of a man who killed a rival who stole his fiancée, in Jeanne Doré by Tristan Bernard (1866–1947). In 1914 Bernhardt was made a Chevalier of France’s Legion of Honor.

Later Years and Death

During World War I Bernhardt visited French soldiers at the front and participated in a propaganda film, Les Mères françaises. That year, at the age of 70, she left for her last American tour, which continued for eighteen months. She was received as a celebrity and spoke at public gatherings urging the Americans to join the Allies. Deprived of the possibility of moving freely on stage, it was her golden voice that kept her audience enthralled. In 1920 Bernhardt played in Racine’s Athalie, presenting the monologue of an aging woman. She continued to perform in Daniel by Louis Verneuil (1893–1952) and in La Gloire by Maurice Rostand (1891–1968). In the fall of 1922 she gave a benefit performance to raise money for Madame Curie’s laboratory, acting in Verneuil’s Régine Armand. Early in March 1923, a Hollywood agent offered her the title role in La Voyante (The Fortune Teller), a film by Sacha Guitry (1885–1957).

Shortly afterwards, on March 26, 1923, Bernhardt died of uremia. There was a mass participation in Bernhardt’s funeral procession from her house on Boulevard Péreire to the Church of Saint François de Sales and from there to her last resting place in Père-Lachaise cemetery.

Bernhardt wrote poetry, prose, and plays. In 1878 she published a prose sketch, Dans les nuages; les impressions d'une chaise (translated as “In the Clouds,” in Memoirs of Sarah Bernhardt, 1977). She wrote two plays in which she acted: a one-act melodrama of adultery, L’Aveu (1888), and a sketch of four acts, Un cœur d’homme (1911). She also made an adaptation of the drama Adrienne Lecouvreur (1907). She wrote an autobiography, Ma Double Vie (1907), and two fictional accounts of episodes in her life in the novel Petite Idole (1920) (translated into English as The Idol of Paris, 1921) and in Jolie Sosie (n.d.). Her retrospective observation on acting and theater or, rather, on her art, in L’Art du Théâtre (1923) was translated into English as The Art of the Theater (1924).

Aston, Elaine. Sarah Bernhardt: A French Actress on the English Stage. Oxford, New York, Munich: Bloomsbury Academic, 1989.

Bergman-Carton, Janis. “Negotiating the Categories: Sarah Bernhardt and the Possibilities of Jewishness.” Art Journal, Vol. 55, no. 2 (Summer 1996): 55–64.

Brandon, Ruth. Being Divine: A Biography of Sarah Bernhardt. London: Vintage, 1991.

Cobrin, Pamela. “She’s old enough to be a beautiful young boy: Sarah Benrhardt, breeches roles and the poetics of aging.” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 22 (1), 47-66.

Duckett, Victoria. Seeing Sarah Bernhardt: Performance and Silent Film. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Duckett, Victoria. Transnational Trailblazers of Early Cinema: Sarah Bernhardt, Gabrielle Réjane, Mistinguett. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023.

Gilman, Sander L. “Salome, Syphilis, Sarah Bernhardt and the ‘Modern Jewess.’” In Love + Marriage = Death and Other Essays on Representing Difference, edited by Sander L. Gilman, 65–90. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1998.

Glenn, Susan A. Female Spectacle: The Theatrical Roots of Modern Feminism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

Gold, Arthur, and Robert Fizdale. The Divine Sarah: A Life of Sarah Bernhardt. New York: Knopf, 1991.

Huret, Jules. Sarah Bernhardt. Préface de Edmond Rostand. Paris: c. 1899; English translation by G. A. Raper, London: 1899.

Musser, Charles. “Conversions and convergences: Sarah Bernhardt in the era of technological reproducibility, 1910-1913.” Film History: An International Journal 251 (1-2), 154-174.

Ockman, Carol. “When is a Jewish Star Just a Star? Interpreting Images of Sarah Bernhardt.” In The Jew in the Text, edited by Linda Nochlin and Tamar Garb, 121–139. London: Thames & Hudson, 1995.

Stokes, John, Michael R. Booth and Susan Bassnett. Bernhardt, Terry, Duse: The Actress in Her Time. Cambridge, New York, New Rochelle, Melbourne, Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Symons, Arthur. “Modernity in Venice.” In Studies in Two Literatures. London: 1897, 188f; “The Divine Sarah.” Smithsonian Magazine, 35/5 (Internet: April 15, 2005).