Modern France

From the French Revolution to the twenty-first century, Jewish women in France have undergone radical legal, political, cultural, and religious transformations. The political emancipation of Jews during the French Revolution had a longstanding impact on Jewish women, leading to important transformations in the following decades. During the nineteenth century Jewish women adopted bourgeois gender roles and gained access to education and public visibility in French society. Starting at the end of the nineteenth century, the Jewish community in France was transformed by several waves of migration from Eastern Europe, the Levant, and North Africa. Since the turn of the twentieth century, Jewish women have made major contributions to all spheres of French society.

Jewish women in modern France experienced both the changes in the status of Jews and the changes in the status of women that occurred in the two centuries after the French Revolution. The emancipation of the Jews of France during the Revolution marked a significant shift in the civic and political rights of Jews: France was the first European country to accord citizenship to its Jews. The career open to talent became a reality for many Jewish men in nineteenth-century France, but Jewish women began to play a public role in French life only with the opening up of opportunities for women at the turn of the twentieth century. Their being women determined their fate, more than their Jewishness, except for in the Holocaust years.

The Nineteenth Century

Political emancipation affected Jews differentially, depending on their place of residence and their socio-economic status. Of the almost forty thousand Jews who lived in France at the time of the Revolution, the most acculturated were the Sephardim of the Southwest, descendants of Spanish and Portuguese conversos. However, the vast majority, more than three-quarters, of the forty thousand Jews in France, were the Yiddish-speaking Ashkenazim of the eastern provinces of Alsace and Lorraine. Living for the most part in villages, they supported themselves as peddlers and cattle dealers, or commission agents, lending money on the side. Jews saw emancipation as an opportunity to free themselves of the economic restrictions of the ancien régime (the period before the Revolution). The most ambitious migrated to cities, especially Paris.

Household and Economic Roles

Jewish women were primarily concerned with their domestic obligations. In the first three generations after the Revolution, they continued their traditional roles, maintaining the household and raising their children. They also played an economic role in the family, as they had before emancipation. A talent for efficient and thrifty domestic management was recognized as a valuable asset in a prospective bride. Wives assisted in commercial dealings, in stores located in or near their dwellings, or in petty crafts. Treating them as virtual partners, their husbands often granted them considerable legal economic autonomy. Married women also lent money and held mortgages. Wives who had participated actively in the family’s support—like Alfred Dreyfus’s mother Jeanette, who had worked as a seamstress—retired as their husbands prospered. The two Dreyfus daughters, like their peers, were raised with the goal of entering into advantageous marriages that would free them of economic responsibilities.

Education

Although most French Jews did not qualify financially for the bourgeoisie until the end of the nineteenth century, French Jews adopted bourgeois gender roles a generation earlier. Jewish communal leaders considered education for girls an important component of the project of “régénération,” the moral and economic improvement of the Jewish population. Although Jewish schools for girls were established somewhat later than those for boys—whose first school was established in Paris in 1819—they reflected the recognition that mothers were deemed responsible for the moral development of their children. This was a central tenet of the bourgeois gender ideal, which held that men and women had different character traits and distinct and complementary roles to play in society. A popular French-language prayerbook, written by a rabbi and published in 1848, clearly expressed this point of view. A prayer for the male head of household went as follows:

My God, in your goodness you have given me a wife, the inseparable companion of my passage through this life…May I never forget that if strength and reason are the perquisite of my sex, hers is subject to the weakness of body and the feeling of the soul; do not permit me, Lord, to be unjust toward her and to demand of her qualities that are in no way in her nature…May her weakness even be her support against my strength; for it would be cruel to take unfair advantage of it toward a weak and delicate being whom love and law have conferred to my protection.

These sentiments did not guarantee specific behavior on the part of either sex, but they lent religious authority to the bourgeois ideal.

Jewish elites who sought social approbation also realized that modernizing the communal treatment of women signaled to the larger society that Jews had adopted French ways. They were aware, in particular, that the segregation of women in public Jewish rituals was a visible reminder of the Oriental origin of Jews and Judaism. Beginning in the 1840s, the moderate reformists who dominated the Consistories, the government-recognized organizations of French Jewry, called for the enhancement of women’s role in the synagogue and introduced confirmation for adolescent girls as well as boys.

Theater

Jewish women were publicly visible in nineteenth-century France in a milieu that was not quite respectable, the theater. The actress Rachel (Elisa-Rachel Félix, 1821–1858) was celebrated during her brief lifetime as a major interpreter of the French classics at the Comédie Française, and Rosine Bloch (1827–1912) also had a following. At the end of the century, Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), always seen as a Jew despite her conversion to Catholicism, became the most famous actress in France. The Jewish actresses contributed to the stereotype of “la belle juive,” the beautiful Jewish woman who incarnated femaleness that was both seductive and potentially threatening. The Jewess was exotic and at the same time the quintessential female; she was a sorceress with the potential to do good or bring harm. The Jewish courtesan was a frequent figure in the works of Balzac. In actual French society, Jewish actresses and courtesans were relatively rare. Equally rare, but far more respectable, were the few upper-class Jewish women, like Geneviève Straus (1849–1926), wife of the composer Georges Bizet, who conducted a salon and served as muse to Marcel Proust.

In popular discourse the Jewish woman was perceived more as a woman than as a Jew. With the development of political antisemitism in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and especially at the time of the Dreyfus Affair, Jewish women appeared in caricatures that stressed not their allure but their negative Jewish traits. They were presented as fat, ostentatiously rich companions to their stockbroker or banker husbands, and, like them, they spoke French with thick German accents.

Immigration from Eastern Europe

At the end of the nineteenth century, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, most from Poland-Lithuania, became a substantial component of French Jewry. About forty-four thousand settled in France in the years 1881–1914, the majority arriving after the failed Russian revolution of 1905, contributing to a total Jewish population of some eighty thousand in 1900, which grew to one hundred and fifty thousand two decades later. (With the loss of Alsace-Lorraine as a result of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the number of Jews in France had declined significantly.) About one-third of the eastern European immigrants were female. Yiddish-speaking immigrant Jews who concentrated in Paris and a few other cities, were primarily working class, laboring in large numbers in various sectors of the garment industry and in other artisan trades. Married women, whose contribution to the family economy was not likely to be noted in census data, assisted in the family’s support by taking in piece work at home, caring for boarders, or helping out in the store. In the interwar period more than twenty percent of job applicants at a communal charitable employment agency were women. Women participated in all the cultural and political activities of the vibrant immigrant Jewish community, which flourished until World War II. They took their place as novelists and poets in the Yiddish cultural world. They also participated in a variety of political movements—Bundist, Communist, and Zionist—which were largely independent of French and French Jewish organizations.

There were also young east European immigrant Jewish women who were drawn to France by the possibility of studying in French universities. In the decade before World War I, for example, Russian and Romanian women, most of them Jewish, comprised more than one-third of all the female students at the University of Paris and about two-thirds of those of foreign origin.

Twentieth Century

Immigration from the Levant and North Africa

A smaller group of Jews, from the Levant as well as North Africa, also settled in France, often in southern cities as well as Paris. Their numbers grew somewhat after World War I, with the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire. Unlike the Jews from eastern Europe, they concentrated in mercantile occupations. In the interwar years about a quarter of women of working age were employed in commerce and the garment industry, and, by the 1930s, increasingly in clerical work. Because they had been educated in schools of the Alliance Israélite Universelle and were familiar with French culture, although they maintained their own synagogue (the Association Culturelle orientale israélite de Paris, created in 1909), they tended to participate more freely in already existent Jewish organizations than did Polish immigrants.

Philanthropy and Politics

In both the native and immigrant communities, women took part in philanthropic activity. Bourgeois women's roles included charitable work, and traditional Jewish society had sponsored associations that were the responsibility of women. In the first part of the twentieth century Jewish women participated in a secondary role in Jewish communal charities, even while their own charitable associations proliferated.

World War I expanded women’s horizons, affirming their philanthropic role and leading to their involvement in political issues. Native and immigrant women even cooperated during the war to establish the Aide fraternelle au soldat and to organize a benefit for war widows. French Jewish newspapers reported in the 1920s and 1930s on such Jewish women’s associations as Paris’s “L’Oeuvre des Femmes en Couche,” an organization founded in 1850 to help mothers with their newborn children, and Mulhouse’s Société des Dames, which held sewing classes to respond to the economic crisis of the Depression. In 1930 the wife of the rabbi of the Sephardi consistorial synagogue in Paris established the organization Protection de l’Enfance Sépharadite. In a 1926 internal report on the Paris Jewish community’s extensive charitable and educational ventures the Consistory affirmed a gendered division of labor, pointing out that each philanthropic institution “appeals largely to the practical aptitudes and the qualities of devotion particular to each sex.” The administrative decision-making of the umbrella group, the Comité Israélite de Paris, for example, was exclusively in the hands of men; the subcommittee that distributed charitable assistance to poor families was entirely female.

Local work, though, was not merely a continuation of women’s charitable work of the mid-nineteenth century. French Jewish women took the initiative to establish new associations, such as one in Paris dedicated to the physical education of Jewish youth. They used an established organization such as the Association Israélite pour la Protection de la Jeune Fille to deal with a contemporary concern: persuading immigrant women from Eastern Europe to have civil marriages in addition to religious ones, to mitigate the misfortune of abandoned wives.

Zionism

The arena in which Jewish women established the greatest number of new organizations in the interwar period was Zionism. But women’s Zionist activism often mirrored traditional women's philanthropy, simply applied in a new context. In 1924, for example, women founded the Union des Femmes Juives pour la Palestine, which donated money to a women’s agricultural school in Nahalal and became the French section of WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization). In the 1930s both the Paris-based Union des Femmes Juives and the Union des Dames Juives of Strasbourg sent regular donations to WIZO in Palestine for a childcare center in Tel-Aviv called Mothercraft Training Centre.

The Union des Femmes Juives demonstrates, however, that women’s organizations were not merely philanthropic. It was headed by the lawyer Yvonne Netter (1889–1985), a fully acculturated French Jew, who was active in both Jewish and general philanthropic, political, and feminist issues. In the interwar years, she combined her Zionist work with the presidency of the Société pour l’amélioration du sort de la femme, which was established in 1876. In 1926 the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs invited the Union des Femmes Juives to send a representative to the ministry’s bureau of religious affairs. Although Jewish women in France could not boast of significant victories for women within their own communal institutions, they mirrored the situation of women in French politics; France was a country that introduced women’s suffrage only in 1945. In the interwar period Jewish women did at least succeed in raising the issue of women’s right to be elected to the consistory in the pages of L’Univers israélite, a major communal periodical.

French representatives also participated in the two World Congresses (the second was called a World Conference) of Jewish Women that took place in Vienna in 1923 and in Hamburg in 1929. The Congress saw its tasks as dealing with religious and educational as well as social and economic issues that affected women, exploring the potential use of the League of Nations to protect women and girls, and supporting the endeavors of Jews in Palestine. The resolutions of the 1929 conference dealt primarily with specifically Jewish issues of education, Palestine, equal rights for women in all communal institutions, and the need to educate Orthodox rabbis to address the problems of women in Judaism. It also expressed support for the general issue of peace activism, which attracted Jewish women in France as well as many politically active women worldwide.

Suffrage and Peace Movements

As women took more prominent public roles in France in the twentieth century, Jewish women whose Jewishness was incidental to their identities were prominent in local and international suffrage and peace movements. Perhaps the most ubiquitous woman of Jewish descent in France was the political journalist Louise Weiss (1893–1983), who was active in public life even in old age. In 1979, when she was eighty-six years old, she was selected to deliver the opening remarks at the European Parliament in Strasbourg. A strong advocate of women’s equality and of democracy, in 1918 she created the weekly L’Europe Nouvelle and later the Ecole de la Paix, which sponsored lectures on the peace movement. In 1934 she founded the feminist association, La Femme Nouvelle, which she served as president. Another Jewish activist, Cécile Brunschvicg (1877–1946), was secretary-general of the preeminent French suffrage organization, the Union française pour le suffrage des femmes, founded in 1909. In the 1920s and 1930s she served as its president. Her entry into the highest echelons of the state when she became one of three female undersecretaries of state in Léon Blum’s 1936 Popular Front government was considered a sign of the growing respect for female equality in France. Another feminist activist, Suzanne Schreiber-Crémieux (1895–1976), the daughter of a senator, was active in Radical Party politics, becoming vice-president of the party in 1929. In 1931 the Radical Party enabled another Jewish feminist, Marcelle Kraemer-Bach (1896?–1990), to be appointed to a responsible position in the Ministry of Public Health.

Christine Bard, a historian of French feminisms of the period 1914–1940, has pointed out that the Jewish women who were so prominent in French feminist life were discreet about their Jewishness. They were aware that the Right regarded feminism as enjuivé (Judaized). Still, none denied their Jewishness, and some, like Cécile Brunschvicg, married in a Jewish ceremony.

Culture

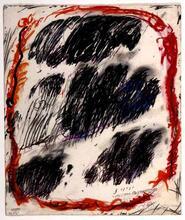

Jewish women were also active in cultural fields. Several, such as the opera singer Lucienne Breval (1869–1935), made their mark in the world of music; others, like Marthe Brandes (1862–1930), achieved prominence as actresses. A few Jewish women, among them the sculptor Chana Orloff (1888–1968) and the painter and textile designer Sonia Delaunay (1885–1979), were part of the avant-garde circle of Montparnasse, the international movement of artists in Paris. Among the Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, several women achieved fame as novelists, including Irène Némirovsky (1903-1942), Elsa Triolet (1896-1970), and Nathalie Sarraute (1900-1999).

World War II

About three hundred thousand Jews lived in France at the outbreak of World War II. Like all Jews, Jewish women became vulnerable to Nazi and Vichy persecution during the war. They were subjected to racist laws, wore the yellow star, and accounted for about 43 percent of the seventy-seven thousand Jews deported, of whom fewer than two percent survived. Their lower percentage among the deportees suggests that they were able to be hidden more easily than men and that they may have had more ties with non-Jews in the larger society. Women participated in providing relief to those interned in camps in France and were particularly prominent in caring for and rescuing children, tending them in group homes and placing them with Christians who agreed to hide them. Women like Anny Latour and Paulette Fink (b. 1911-2005) also fought in both the general and Jewish armed Resistance. After the war, women made important contributions to the reconstruction of Jewish life in France. For example, Éliane Amado Levy-Valensi (1919-2006), a French philosopher and psychoanalyst with roots in Algeria and Salonica, was central to the renewal of French Jewish thought as the only woman of the “École de pensée juive de Paris,” alongside towering intellectual figures such as Emmanuel Levinas and Léon Askénazi.

Post-War Period

In the postwar years, the face of French Jewry was transformed with the mass migration, beginning in the 1950s, of North African Jews from Morocco, Tunisia, and Algeria. Sephardim became the majority of the French Jewish community, bringing with them their liturgical, culinary, and musical traditions, such as Chaabi music. Algerian-born Jewish singers Sultana Daoud, known as “Reinette l’Oranaise” (1915-1998), and Line Monty (1926-2003) were among a number of immigrant artists who introduced French audiences to Arab-Andalusian music from North Africa. According to a sociological study conducted in 1972, more Jewish women of Moroccan, Tunisian, and Algerian origin defined their Jewish identity as “religious” than did their male peers. However, of the one-third of the community who saw their Jewishness in non-religious terms, again, more were women, perhaps a reflection of the lesser Jewish education given to females than males. With the destruction of most of European Jewry, France’s Jewish population, estimated at six hundred thousand at the end of the twentieth century, became the largest Jewish community in Europe (with the exception of the Soviet Union and its successor states).

At the same time women became ever more visible in public life as they entered the educational institutions that prepared individuals for careers in academic and in civil service. Jewish women, too, participated fully in French life. Initially, they were for the most part not drawn from the new North African immigrants, but in the last two decades of the twentieth century Sephardi women also achieved mobility. Sephardi immigrants have educated their daughters as well as their sons in secular studies, and in their aspirations for their children they express preference for them to enter the salaried professions, the civil service, and the liberal professions rather than commerce. Their daughters have realized their dreams.

In the academic world Jewish women became professors in a variety of fields. Former member of the Resistance Annie Kriegel (b. 1926–1995), Elise Marienstras, Lucette Valensi, Françoise Basch, and Claudie Weill have written important works of history. Annie Cohen-Solal (b. 1948), born in Algeria, is best known for her biography of the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, but, with a Ph.D. in literature from the Sorbonne, she has taught at both French and foreign universities and has also published on American art. Another Algerian-born Jewish woman, writer and literary critic, Hélène Cixous (b. 1937), established the first center devoted to feminism at a European university, at the University of Paris VIII. The field of Jewish Studies, in particular, has drawn a number of women scholars: Renée Bernheim-Neher (1922-2005), Rachel Ertel (b. 1939), Annette Wieviorka (b. 1948), Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, Esther Benbassa (b. 1950), American-born Nancy Green, and Rita Thalmann (1926-2013), all in history; Doris Bensimon (1924-2009) and Dominique Schnapper (b. 1934) in sociology; and Blandine Kriegel (b. 1943) in philosophy. Beginning in the prewar years, Jewish women also achieved significant positions in science and medicine, particularly in the fields of molecular biology, biochemistry, and chemistry. They also expanded their presence in law, a field that became open to women in France early in the twentieth century. One of France’s most notable lawyers was Tunisian-born lawyer Gisèle Halimi (1927-2020), a life-long defender of women's rights who was instrumental in decriminalizing abortion and homosexuality in France.

Jewish women have also been visible in entertainment, in broadcasting, and in politics. Although antisemites have attacked the presence of Jews in public life, Jews seem to have achieved widespread acceptance. Simone Signoret (1921–1985) was one of the most popular actresses in France and internationally during her long career. Anouk Aimée (b. 1932), too, has been seen as one of the stars of French cinema. Behind the scenes, a number of Jewish women, among them Diane Kurys (b. 1948), have served as film directors and screenwriters. Popular singer Barbara (1930-1997) was viewed by many as an icon of French music. A Jewish woman, the television journalist Anne Sinclair (b. 1948), was even selected in 1989 to represent Marianne, the symbol of republican France.

In addition to her academic work, Annie Cohen-Solal served as the Cultural Counselor at the French Embassy in the United States from 1989 to 1993. Perhaps the single best known French Jewish woman in politics is Simone Veil (1927-2017) who first attracted much attention when she was appointed Minister of Health in 1974 and was internationally acclaimed after she was chosen to be the president of the European Parliament in 1979. In 2018, Veil received a rare state funeral, and she became the first French Jewish woman buried at the Pantheon, alongside other illustrious French personalities such as Voltaire and Victor Hugo. Simone Veil’s death, followed a year later by that of her fellow Auschwitz survivor and lifelong friend Marceline Loridan-Ivens, has raised questions about how to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive as the number of survivors in France is rapidly dwindling.

Twenty-First Century

Secular Life

Although France still lags behind some of its European neighbors with regards to gender parity in politics, several other Jewish women have held prominent political roles. Algerian-born lawyer Nicole Guedj (b. 1955) joined the French Ministry of Justice in 2004 and 2005. Audrey Azoulay, the daughter of the adviser to king Mohammed VI of Morocco, was France’s Minister of Culture from 2016 to 2017, before becoming the second woman appointed as UNESCO’s Director-General. Most recently, the prominent hematologist Agnès Buzyn (b.1962), the daughter of two Holocaust survivors and Simone Veil’s former daughter-in-law, served as Minister of Solidarity and Health from May 2017 to February 2020. In that role, Buzyn was involved in President Emanuel Macron’s first major social reform: the adoption of a controversial bill granting single women and homosexual couples free access to fertility treatments.

Well-educated and generally middle-class, Jewish women in France now partake of the rights accorded to Jews and women as citizens of the French state. Their access to virtually all positions in society reflects the gradual extension in the twentieth century of full civic and political rights to women. As women, they were fully emancipated more than a century after France proclaimed the liberation of the Jews.

Cultural and secular Jewish non-profit associations have provided fertile ground for female activism and leadership. As volunteers, philanthropists, and leaders, women are prominently involved in Jewish cultural and memorial foundations, as well as humanitarian organizations. For example, as anthropologist Jessica Roda has shown, women make up the bulk of France’s Judeo-Spanish associations. Present and former directors of major French Jewish secular institutions include Jacqueline Keller at CRIF (Conseil Representatif des Institutions Juives en France) (1981-1996), Nelly Hansson at the Fondation du Judaïsme Français (1993-2010), Laurence Sigal at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme, Nicole Goldmann at the Fonds Social Juif Unifié, Patricia Sitruk at OSE, Karene Fredj at the Fondation Casip-Cojasor, and Anne-Marie Revcolevski at the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah.

Religious Life

Somewhat paradoxically, although in recent decades Jewish women have been able to rise to top positions across all areas of secular life, in their religious and communal lives they have struggled to access the same opportunities as their male coreligionists. In part, the gender imbalances prevalent in French Jewish religious life can be explained by France’s religious and political historical trajectory, including its Catholic heritage, and the highly centralized nature of the Jewish community, dating back to Napoleonic policies. In contrast to the United States, for instance, religious pluralism within French Judaism appears relatively limited. (American denominations are of little use for understanding France’s Jewish ritual landscape, as progressive movements—“mouvement libéral” and “mouvement Massorti”—are underrepresented in France and tend to be more religiously conservative than their American counterparts; also, France has no equivalent of Modern Orthodoxy.) More than a century after consistorial rabbis lost state funding as a result of the 1905 Law of Separation between the Church and State, the Consistory system has continued to represent the Jewish community’s religious interests vis-à-vis the French state and to function as the main institution in French Jewish religious life. Among the French Jews affiliated with Jewish institutions (a minority within the community), the vast majority attend consistorial synagogues. Even unaffiliated Jews tend to turn to consistorial services on the rare occasions when they participate in ritual life.

While the centralization of Jewish religious authority around the Consistory proved particularly successful in facilitating the integration of North African Jews into French communal life in the 1960s and 1970s, it also came at a cost. In recent years, a growing number of voices stemming from both within the progressive streams of French Judaism and from the Orthodox community itself have been critiquing consistorial institutions for discriminating against women in their midst. The precarious status of women in French religious life is not merely a remnant of the past but rather a consequence of the Consistory’s turn towards Jewish ultra-Orthodoxy dating back to the 1980s, and furthered in the 1990s and 2000s. Under the influence of French Jewish men schooled in Orthodox yeshivot abroad (including in the United Kingdom, Israel and Morocco), consistorial authorities adopted increasingly stringent religious practices that widened the gender imbalance between practicing Jewish men and women and led to growing gender separation in Jewish life, including in Torah classes and communal activities. Most symbolic of this heightened gender separation within consistorial institutions in recent decades is the turn to a larger Synagogue partition between men and womenmehizah in many communities, in order to increase the physical separation between the genders.

Since the 2010s, a small number of Orthodox Frenchwomen have raised public criticism of gender roles in the French Jewish liturgical space. Most prominent among them is the (Consistory-affiliated) Talmudic scholar Liliane Vana. Inspired by the actions of Modern Orthodox Jewish feminists in the United States and Israel, in 2012 Vana founded a group named “Lecture Sefer” with the goal of organizing women’s prayer groups across France. The following year, the newly established group organized an unprecedented and controversial Torah reading by women in the Parisian suburb of Neuilly, on the occasion of Lit. "rejoicing of the Torah." Holiday held on the final day of Sukkot to celebrate the completing (and recommencing) of the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah (Pentateuch), which is divided into portions one of which is read every Sabbath throughout the year.Simhat Torah. Men attended the reading and the organizers abided by the physical separation between the genders while adopting a slight but symbolic change: women were seated parallel to the men, rather than behind the mehizah as is customary in French Orthodox synagogues. This initiative provoked the ire of consistorial leaders, including Michel Gugenheim, the Chief Rabbi of Paris at the time, who denounced it in 2013 as “an open breach towards the modification of Judaism” and accused its originators of threatening the future of Orthodox Judaism: “These women do not understand how risky their actions are. History has shown that the Conservative and Reform movements were born out of similar small changes and not from a desire to revolutionize all of Jewish practice right away.” Since this first Torah reading, “Lecture Sefer” has continued to organize Torah readings by women on Holiday held on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (on the 15th day in Jerusalem) to commemorate the deliverance of the Jewish people in the Persian empire from a plot to eradicate them.Purim and Simhat Torah across France.

Criticism of French Jewish institutions, especially consistorial ones, is not limited to the place of women in French synagogues. In 2006, Jewish sociologist Sonia-Sarah Lipsyc (who left her native France for Montreal in 2008) issued a report for the Jewish feminist organization WIZO, in which she highlighted the difficulties that Jewish women in France faced in obtaining the religious bill of divorce (get). In 2014, this issue became highly publicized in the French press, when the Paris rabbinical court was accused of facilitating the blackmail of a Jewish woman who was pressured into paying thousands of dollars in exchange for obtaining a divorce. Since the 2000s, a number of Jewish women have advocated for changes in the marital sphere, including lawyer Annie Dreyfus, prominent writer Eliette Abécassis, who published a novel on Jewish divorce in 2011, and journalist Olivia Cattan, who established an association promoting gender equality within French Judaism. Additionally, in recent years, French Jewish woman have bemoaned the dearth of religious educational opportunities available to them. While access to the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud has been increasing exponentially in other Jewish communities worldwide, particularly in the Anglophone world, in France most Jewish women and girls, including those schooled in Jewish schools, are not taught the Talmud. To remedy this situation, Joëlle Bernheim, a psychoanalyst and the wife of a former Chief rabbi of France, established in 2012 France’s first Jewish house of study for women, “Beth Hamidrash Lenashim,” located in Paris’ largest synagogue, the Synagogue de la Victoire.

Finally, Jewish women have also denounced the lack of access to top lay positions within consistorial institutions. Although women gained access to administrative posts at the Paris Consistory starting in 1990s, they are still largely underrepresented among communal leadership positions. In 2006, Janine Elkouby, a former literature professor at the University of Strasburg, sparked controversy when she registered her candidacy to join the governing body of the Consistory in the Bas-Rhin (which forms part of the Alsace region), despite that institution’s decision that women were not eligible. Following rabbinical opposition to her participation in the community’s lay leadership and the local Consistory’s refusal to consider her candidacy, Elkouby brought her case against Chief Rabbi René Gutman to the administrative tribunal and won. Following this legal victory, in 2008 she became the first woman to be elected vice-president of the Consistory in the Bas-Rhin. In 2016, the controversy surrounding Evelyne Gougenheim’s candidacy for president of the Central Consistory echoed the Elkouby case; although women are eligible for this post, Gougenheim faced a great deal of pressure from Orthodox rabbis to withdraw her candidacy, and, unlike Elkouby, she lost the election.

Despite the predominant role of the Consistory in French Jewish religious life, religious pluralism within Judaism seems to be slowly rising in France, in part due to the choices and actions of Jewish women. Although the Consistory continues to attract the majority of affiliated French Jews, both non-Orthodox streams of Judaism and non-consistorial Orthodox movements are gaining more and more members. Within Orthodoxy, Chabad-Lubavitch, which is by far the most numerically important and well-known Hasidic movement in France, has been developing at a fast pace since the 1960s. In past decades, the proliferation of Chabad synagogues and childhood institutions (schools, kindergartens, summer camps) has helped further disseminate norms of gender segregation. In 2020, Chabad-led schools, which are not co-ed, represented 21% of France’s Jewish day schools. As sociologist Laurence Podselver has pointed out, the growth of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement in France is tied to the phenomenon of female “baalei teshuvah” (Jews who became observant) of North African descent, in the decades that followed the mass Jewish arrivals from North Africa. In response to the break-up of the family resulting from immigration, as well as a perceived crisis of values within the secular world, myriad French Jewish women, for the most part the daughters of immigrant parents from working-class backgrounds, joined the Chabad-Lubavitch movement, typically after their high school studies. Today, the majority of Chabad-Lubavitch affiliates in France are Jews of North African descent who have broken with Sephardic traditions in favor of Ashkenazi customs.

For French Jewish women affiliated with progressive Jewish movements, the situation is quite different from that of the female adherents to consistorial and Chabad-Lubavitch Judaism. Liberal streams of Judaism, while still relatively little represented in France, are nonetheless growing at a slow pace, in part due to the gender disparities within the majority of Jewish congregations that many Jews (male and female) lament. The Massorti movement is the smallest, with only six communities nationwide. Approximately fifteen communities in France are affiliated with Reform Judaism, serving approximately 20,000 members (out of 150,000 men and women who attend religious services). In 2019, France’s two main Reform congregations founded the association “Judaïsme en movement” (Judaism in motion), in the hopes of diversifying the French Jewish communal landscape and giving more voice to Reform Judaism, thereby creating an alternative to the Consistory.

In France’s non-Orthodox synagogues, women’s active participation in religious services, such as the attribution of ritual honors and Torah reading, came relatively late compared to the United States. While one Reform congregation (Mouvement juif libéral de France, or MJLF) permitted Torah reading by women in 1977, another (synagogue de la rue Copernic) started allowing it only in 2014. Similarly, in the Massorti congregation Adath-Shalom, women did not get called up to the Torah until the 2000s. According to sociologist Beatrice de Gasquet, the belated feminization of ritual within progressive congregations in France, in contrast to the United States, is a direct consequence of the divergent histories of feminism on both sides of the Atlantic. In the context of a backlash against the women’s movement (often decried as an American import), the leadership of Reform Judaism in France expressed a reluctance to adopt practices that could be criticized by the majority of French Jews as too feminist. For many Jewish women in non-Orthodox congregations, their acceptance into a greater number of ritual practices in the 2000s left a deep impression—during her fieldwork, de Gasquet witnessed “elderly women who are visibly emotional when going up to Torah for the first time, and say the blessing with a trembling voice before returning to their seat with tears in their eyes.”

Reform congregations introduced another revolution in the French Jewish landscape: the ordination of female rabbis. There are currently four female rabbis in France—all of whom were trained and received rabbinic ordination abroad (either in the United Kingdom or in the United States). The first woman to become a rabbi in France was Pauline Bebe, who was ordained at Leo Baeck College in London in July 1990, almost twenty years after the ordination of the first female rabbi in the United-States. Five years later, Pauline Bebe left the MJLF to establish her own synagogue, the Liberal Jewish Community (Communauté juive libérale, or CJL). In the newly established synagogue, Rabbi Bebe introduced several new practices aiming to further gender equality in ritual life, including the wearing of the prayer shawl by women. Delphine Horvilleur, from the MJLF, was the second female rabbi in France. Horvilleur received her ordination in New York in 2008, after leaving behind a successful career as a journalist. In recent years, Rabbi Horvilleur has become one of the most prominent voices of Judaism in France, despite belonging to a minority movement within the French Jewish community. Horvilleur is regularly featured in the French general press—in January of 2020, she appeared on the cover of Elle magazine, with the headline “rabbi, intellectual, feminist”—especially in discussions pertaining to antisemitism in France and interfaith dialogue. Horvilleur has been at the forefront of Muslim-Jewish dialogue, and in 2017 she co-wrote a book with scholar of Islam Rachid Benzine, exploring the “thousand and one ways of being Jewish or Muslim.” As the editorial director of the French Jewish magazine Tenou’a, and the author of several books exploring the intersection of Judaism, gender, and the family, Horvilleur has also been a prominent advocate for gender equality within religion and has championed greater dialogue between the different branches of French Judaism on this matter. In 2013, French-born Floriane Chinsky, who became Belgium’s first female rabbi in 2005, joined Horvilleur’s congregation as a rabbi. Finally, France’s fourth, and most recently ordained, female rabbi is Daniela Touati, the Romanian-born daughter of Holocaust survivors. Touati received her ordination in London in 2019 and currently holds a rabbinical post at a Reform synagogue in Lyon.

It bears noting that although all female religious leaders in the French Jewish community belong to the Reform movement, several French-born Jewish women living abroad have been able to enact changes within other denominations, especially in Israel. For instance, in 1993, Valerie Stessin became the first woman to receive rabbinical ordination from the Conservative movement in Israel. In 2016, Bitya Rozen-Goldberg was among the first women to obtain an Orthodox rabbinical ordination in Israel, and she has been promoting a pluralist vision of Orthodox Judaism through Ta Shma, the Jerusalem-based Francophone Houses of study (of Torah)bet midrash she is currently directing. As of today, Rozen-Goldberg is the only French Orthodox female rabbi. Another French-born Orthodox immigrant to Israel, Nathalie Loewenberg, illustrates the new types of religious leadership roles available outside of France. As yoetzet halacha (female halachic advisor), Loewenberg provides ritual advice on family purity to Jewish women in Israel and in France, where she travels regularly. While these women have chosen to relocate in Israel, Myriam Ackermann-Sommer, who is currently training at Yeshivat Maharat in New York to become an Orthodox rabbi, is hoping to return to France after rabbinical ordination and to contribute to the growth of a pluralistic Jewish Orthodox landscape.

The emergence of heated debates about gender equality within consistorial Judaism; of French female Reform rabbis trained outside of France; and of French-born religious leaders living abroad, points to the increasingly transnational nature of French Judaism and the growing impact of the ongoing developments unfolding in Israel and the United States. In an era of intensified migrations of both bodies and ideas (especially through social media), French Judaism seems more and more connected to the rest of the world. It remains to be seen whether progressive movements will succeed in rivaling the authority of the Consistory, and whether feminist activists will be able to develop a new type of Judaism in France that may be comparable to American Modern Orthodoxy.

Finally, these religious and cultural developments are occurring against the backdrop of the resurgence of antisemitism in France since the 2000s. In the past two decades, acts of violence against Jews have prompted myriad families to leave their neighborhoods, or even to leave France altogether (primarily to Israel, and, to a smaller extent, to England, Canada, and the United States). In the first nine months of 2018, for instance, antisemitic incidents in France increased by 69%. Although antisemitism takes several forms, in the most tragic cases anti-Jewish hatred has resulted in the killings of several French Jews, including women. Among them were Elsa Cayat, a psychoanalyst and columnist, who was murdered during the 2015 attack on the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. The gruesome assassination of two elderly Jewish women, Sarah Halimi (Lucie Attal) and Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll, in two separate episodes in 2017 and 2018, profoundly shocked the Jewish community. In conclusion, Jewish women in France are currently facing both new opportunities and challenges; how they respond to this complicated state of affairs will determine not only their personal trajectories, but also the future of Judaism in France.

Arkin, Kimberly A. Rhinestones, Religion, and the Republic: Fashioning Jewishness in France. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2014.

Azria, Régine. “Being a Jewish Woman in French Society.” In Jewish Women 2000: Conference Papers from the HRIJW International Scholarly Exchanges 1997-1998, edited by Helen Epstein, 65-70. Waltham, Mass.: Hadassah Research Institute on Jewish Women, 1999.

Bard, Christine. Les filles de Marianne. Paris: Fayard, 1995.

Benbassa, Esther. The Jews of France. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999.

Bensimon, Doris and Sergio Della Pergola, La Population juive de France. Jerusalem: Institute of Contemporary Jewry of Hebrew University and Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris: 1984.

Bensimon-Donath, Doris. Socio-Démographie des France et d’Algérie, 1867–1907. Paris: POF, 1976.

Berkovitz, Jay. The Shaping of Jewish Identity in Nineteenth-Century France. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1989.

Bertin, Célia. Louise Weiss. Paris: Michel, 1995.

Birnbaum, Pierre. The Jews of the Republic. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1986.

Bitton, Michèle. 110 Femmes Juives Qui Ont Marqué La France: XIXe et XXe Siècles. Nantes: Éditions Normant, 2014.

De Gasquet, Béatrice. “Masculinité Et Sens Des ‘Honneurs’.” Travail, Genre Et Sociétés 27, no. 1 (2012): 91-107.

De Gasquet, Béatrice. “‘Dépasser L’interdit’. Le Châle De Prière Des Femmes En France Au XXIe Siècle.” Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, no. 44 (2016): 123-46.

De Gasquet, Béatrice. “Le Balcon, Les Pots de Fleurs et La Mehitza: Histoire de La Politisation Religieuse Du Genre Dans Les Synagogues Françaises.” Archives de Sciences Sociales Des Religions, no. 177 (March 1, 2017): 73–95.

Elkouby, Janine, and Julianne Unterberger, eds. Être femme et juive au 21e siècle. ACSIReims éditions, 2009.

Green, Nancy. The Pletzl of Paris. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1986.

Green, Nancy. Ready to Wear, Ready to Work. Durham, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

Hyman, Paula E. The Emancipation of the Jews of Alsace. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

Hyman, Paula E. From Dreyfus to Vichy. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979.

Hyman, Paula E. The Jews of Modern France. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1998.

Kaplan, Zvi Jonathan, and Nadia Malinovich, eds. The Jews of Modern France: Images and Identities. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2016.

Klein, Luce. Portrait de la Juive dans la littérature française. Paris: Nizet, 1970.

Las, Nelly. Jewish Voices in Feminism: Transnational Perspectives. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.

Lipsyc, Sonia Sarah, ed. Femmes et judaïsme aujourd’hui. Paris: In Press, 2008.

Podselver, Laurence. Retour Au Judaïsme: Les Loubavitch En France. Paris: Jacob, 2010.

Poznanski, Renée. Jews in France during World War II. Hanover, NH: Brandeis University Press, 2001.

Reynolds, Siân. France Between the Wars: Gender and Politics. London: Routledge, 1996.

Roda, Jessica. “Re-Making Kinship. From Community to Family: A Sephardic Experience in France.” Théologiques 24, no. 2 (July 12, 2018): 97–120.

Schreier, Joshua. Arabs of the Jewish Faith. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010.

Szwarc, Sandrine. Éliane Amado Lévy-Valensi: Itinéraires. Paris: Hermann, 2019.

Tangi, Myriam. Mehitza: Seen by Women = Ce Que Femme Voit. Jerusalem, Israel : Springfield, NJ: Gefen Publishing House Ltd. ; Gefen Books, 2016.

Zuccotti, Susan, The French, the Jews, and the Holocaust. New York: Basic Books, 1993.