Orthodox Judaism in the United States

In September 1954, an inaugural class of thirty-two students enrolled at Stern College for Women, as Yeshiva University opened the first Jewish liberal arts college for women in America. In this picture from Stern's first commencement in 1958, New York City Mayor Robert F. Wagner, flanked by Yeshiva University Dean Dr. Samuel Belkin, presents certificates to Shirley Pasternak and Anika Wintner, members of the college's first graduating class.

Institution: Yeshiva University, New York

Throughout American Jewish history, the issues of if, and, how, women might participate in religious life has been a major point of differentiation among that group’s variegated leadership and laity. Until recently, among the most recurring issues were whether women could have all the rights of synagogue membership that men possessed and to what degree women could have access to both rudimentary and advanced religious educational opportunities. Until the post-World War II period, women took part in congregational life in their own circumscribed “special sphere,” the sisterhood. In recent decades, some Orthodox congregations have moved towards creating more gender egalitarian forms of ritual life within the halakhah. In the first decades of the 21st century, women have assumed Orthodox religious leadership roles, developments that have sparked much controversy within that community.

Introduction

Orthodox views on the role women may play in their community’s religious, educational, and social life have reflected the range of attitudes that religious group has harbored toward American society and culture. Generally, those Orthodox Jews who have resisted American culture and who have attempted to live religious lives reminiscent of their European past have not countenanced the active participation of women within the synagogue. In the most recent generations, some of these Orthodox men and women have loudly opposed what they perceived to be the deleterious impact feminism has made on American Jewish life. They have censured Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist leaders for their broad redefinitions of women’s roles. They have also criticized other segments of the Orthodox community who have pressed the The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah (Orthodox rendering of Jewish law) to allow women greater activity in public ritual and religious leadership. Yet, even the most traditional of Orthodox Jews have come to recognize that modern conditions have necessitated that girls and young women in America receive a more extensive Jewish education than their mothers and grandmothers had. This understanding has inspired the creation of comprehensive Orthodox school systems for girls, which have produced some outstanding Orthodox women educators. This dynamic approach to women’s education reflects, to some extent, Orthodox attitudes that were first expressed in Eastern Europe some one hundred years ago.

For many other Orthodox Jews, the opening of synagogue life to greater women’s participation, within what they see as the expansive boundaries of halakhah, is but another dimension of their accommodating approach to their encounter with America. Those who have altered the architecture of synagogues to make women comfortable at Orthodox services, who have admitted women to their synagogue boards and ritual committees, and who, beginning in the 1970s, first supported the creation of women’s Prayertefillah (Orthodox prayer) groups have all acted in accord with their beliefs that for traditional Judaism to remain vital, it had to and could adjust to the American environment. Even more significantly, during the first decades of the twentieth century, women have assumed Orthodox religious leadership roles. Predictably, resisters of varying types have opposed this major extension of women’s professional religious profile. Meanwhile, even as accommodationists have not always been of one mind over the extent of female participation in religious life, they have been uniformly in favor of providing women with ever increasing Jewish educational opportunities comparable to those accorded men.

1700–1850

The need to increase room for women within the Orthodox synagogue, as they observed services and rituals, was among the issues congregational leaders faced in the earliest periods of American Jewish history. (It must be remembered that the few synagogues established in this country before approximately 1840 adhered to Orthodox rules.) Jewish officials from New York to Philadelphia to Newport to Charleston were concerned that their services and edifices merit the approbation of their non-Jewish friends. They were apprehensive that gentile visitors might look askance at women segregated behind a closed latticed partition, “like a hen coop” as one visitor in 1744 described the women’s section in New York’s Shearith Israel. Accordingly, they designed open galleries that would improve women’s sight lines, without making men immediately aware of their presence. Often, these synagogues engaged Christian architects to facilitate their plans and to implicitly ensure that their synagogues were built for American-style worship. There were no religious discussions about the permissibility of this architectural innovation. It was a generally accepted Jewish adjustment to American life. Likewise, there were no calls, until the 1850s, for men and women to sit together. In colonial New England and elsewhere, separate seating was not uncommon in churches and meeting houses. Thus, the accommodating Orthodox synagogue was in consonance with American mores in having its modern gallery.

But even as women of this period, and men too for that matter, were unconcerned with advocating a role for females in synagogue ritual, some women were interested in greater recognition as members of these congregations. Typically, women’s identities within congregations were subsumed beneath those of their fathers and husbands. Many congregations did accord widows rights as “members” to retain their seats in the synagogue, to be buried in the congregational burial ground, and possibly to send their children to the Jewish school. But women could not vote on synagogue plans and policies. Ultimately, those women who wanted a sense of empowerment and participation within communal life established their own separate benevolent societies that were sometimes affiliated with, and other times separate from, synagogue life. The Female Hebrew Benevolent Society of Philadelphia was one of the most important of these independent organizations. Led by Rebecca Gratz and other women of that city’s Mikveh Israel, it established in 1838 the first Jewish Sunday school in the United States. Offering classes conducted initially by an all-female faculty, it attracted by its second year some eighty boys and girls and was praised by Rabbi Isaac Leeser, the most important Orthodox spokesperson of the pre-Civil War period.

Generally, Jewish education during this time was based in congregational schools where preference in enrollment was given to male applicants. Still, by the 1840s, most synagogue schools were coeducational, although both sexes received little more than rudimentary training in Jewish studies.

1850–1900

With the emergence of Reform congregations in the 1850s, policies on whether men and women could sit together during services was one of the essential points of demarcation between liberal and Orthodox congregations. In the pre-1880 period, membership disagreements over instituting family pews probably caused more splits in once-Orthodox congregations than any other proposed reform. Proponents of change spoke of their respect for women’s equality, the need to attract young people to services, and above all the importance of their synagogue conforming to American social trends. The accommodating Orthodox of that era also wanted to project a modern image to the larger world and were troubled by widespread disaffection from Judaism. But for most Orthodox groups mixed seating was a violation of Jewish law that could not be countenanced. It was also, to their minds, a harbinger of other ritual reforms that would further undermine traditional Judaism.

Despite the halakhic constraints, not all late nineteenth-century American congregations that defined themselves as Orthodox kept the genders apart during prayer. Indeed, when the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America was founded in 1898, a number of its charter constituents had family pews.

Nonetheless, consistent with American Orthodox political traditions, these synagogues, whether they countenanced mixed seating or not, did not ordinarily admit women as members. But in continuing to deny women (except an occasional widow) congregational suffrage, they seemingly differed little from their liberal religious counterparts who polemicized in favor of women’s equality but who denied them membership in their synagogues.

The issue of synagogue membership for women did not concern those Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe who began arriving in this country as early as the 1850s, intent on transplanting the religious civilization they remembered from the old country to these shores. In the ephemeral landsmanshaft (associations based on home-town ties) synagogues, as well as in the larger, more established shuls on New York’s Lower East Side and elsewhere, women had no role in ritual life. Possibly as a concession to the American religious environment on the part of men just beginning to acculturate—or maybe because the gentile architectural firm they hired deemed it appropriate—in landmark synagogues like the Lower East Side’s Eldridge Street’s Kehal Adath Jeshurun, women were able to see services very well from the large open galleries. And women could be of service to their congregation and community through their ladies’ auxiliary fund-raising and mutual aid. Still, at least in the public sphere, men remained the focus of religious attention. For most immigrant rabbis, the key women’s issue had to do with the traditional requirement that proper Ritual bathmikvehs (ritual baths) be established for those who might use them. Leaders were also worried that poorly trained colleagues often issued improperly written Writ of (religious) divorcegittin (writs of divorce). Their great fear was that if remarriage occurred, children from a second union would be Jewishly illegitimate. In 1902, when the Agudath ha-Rabbanim (Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada) was founded, solving the problem of gittin was identified as an important organizational objective.

The central place men occupied in the worldview of those who tried to resist Americanization is best illustrated, however, in their attitudes toward Jewish education and the preventive socialization of their second-generation youngsters. In 1886, a group of the most religious downtowners pooled their limited funds to establish Yeshiva Etz Chaim, a small Lit. "room." Old-style Jewish elementary school.heder for boys. Its mission was to train boys the way young men had been traditionally educated in Eastern Europe and, as important, to keep them away from the assimilatory pressures imposed by this country’s public schools. Analogizing as they did from their Old World pasts, they assumed that in America, too, girls would receive their Jewish training as they always had: informally, at home, from their mothers or from a private tutor. In Russia, most Jewish girls did not go to the government schools. In America, however, they attended the public schools en masse. Because they were thus exposed to systematic English-language and secular training, the pace of acculturation of daughters from the most religious downtown families was far greater than it was for the small number of male scholars who were sent to Etz Chaim and its other yeshivah counterparts that were established around the turn of the twentieth century.

The transplanted Orthodox community’s sense that formal education was for boys alone was also reflected in early admission policies of both the ephemeral, independent heder melamdim (untrained teacher in a one-room tenement school) and of the metropolises’ first afternoon Talmud Torahs. Thus it was a major departure when, in 1894, leaders of the Machzike Talmud Torah, some of whom were also prime supporters of the Etz Chaim endeavor, instituted classes for girls. It was a signal recognition that American conditions required some new approaches toward indoctrinating and socializing young women into the traditional faith.

Outside of New York and other large Orthodox enclaves, where the pool of potential students was very limited, school officials could not as easily stand on law or ceremony in restricting education to boys. While heder melammeds (heder teachers) usually trained only boys in preparation for the youngsters’ Lit. "son of the commandment." A boy who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbar mitzvahs, classes in fledgling congregational or communal schools were often coeducational.

1900–1970

In the first decade of the twentieth century, acculturating Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe and their second-generation children revisited the role women might play in congregational life and emphasized the need to train both girls and boys in the basic principles and practices of Judaism. For example, the Orthodox Union and its youth wing, the Jewish Endeavor Society, which operated both on the Lower East Side and in Philadelphia, offered Americans new modern Orthodox services. As always, men and women were separated by a The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.mehizah during services. But now women, including Miriam Jacobs, Frances Lunevsky, Ida Mearson, and Irene Stern, who were students of Jewish education at the Jewish Theological Seminary, served as members of the board of directors of the society and taught in that organization’s religious schools, which offered classes to both boys and girls. The union and its society’s philosophy was that it was not so important how much girls and boys learned about their faith through their encounter with the synagogue and school. Rather, it was essential for young women and men to be inculcated with an interest in being part of the Orthodox community. Thus, the Orthodox Union supported the New York Kehillah’s educational innovations that were directed at both girls and boys. It was, likewise, the stance of Orthodox schools like the Uptown Talmud Torah and the Rabbi Israel Salanter Talmud Torah, both in Harlem, which worked with the New York Kehillah’s bureau of education and offered separate classes for girls and boys in their neighborhoods.

Concomitant with these efforts, a different strain of transplanted Orthodoxy began to evolve in immigrant neighborhoods, first in Brooklyn and then downtown, which advocated still another way girls might be educated. The first Mizrachi (Religious Zionist) National Hebrew School for Girls was founded in Williamsburg in 1905. Analogizing itself to the modern heders of Eastern Europe (the so-called heder metukkan, or improved or reformed heder), these American schools offered girls a supplementary school curriculum that emphasized Hebrew language, grammar, conversation, and literature. In 1910, a sister school was created on Madison Street in Lower Manhattan. According to one contemporary observer, the “school was confined to the teaching of girls, for two reasons; first, because it was easier to get Jewish parents to permit the teaching of these modern ‘fads’ [that is, Hebrew language and religious Zionism] to girls than to boys, and second, because the nationalist movement made the education of Jewish women an essential part of its program” (Dushkin, p. 83).

In 1929, the scope of Mizrachi-style education for girls took an additional step forward when the Shulamith School, the first American all-day Orthodox school for girls, was established in Brooklyn. In this “girls’ yeshivah,” elementary school students were exposed to a Hebrew-intensive curriculum that was integrated with their general studies. Interestingly enough, in organizing their school, American Mizrachiites drew upon a newly nascent Eastern European model, the bais ya’akov movement, that was being sponsored by their ideological opponents within the Orthodox world, the anti-Zionist Agudath Yisrael.

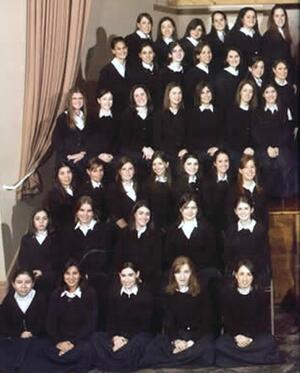

During the post World War I era, Sarah Schenirer, a Polish seamstress with a passion for Jewish tradition, developed the first school system for Orthodox girls in history. By the eve of World War II, the network encompassed over two hundred and fifty schools with more than forty thousand pupils, primarily in Eastern Europe. Pictured here is the second graduating class of the Bais Ya'akov in Lodz, Poland, in 1934.

Institution: Yehudis Bobker, Sydney, Australia.

Beginning in 1917, at the instigation of Sarah Schenirer, some of Poland’s most Orthodox Jews addressed the problem that their counterparts in America failed to address: the growing dichotomy between the socialization of girls and boys. As Schenirer saw it, the best young men were still under the safe influence of the yeshivah. But girls, bereft of formal Jewish education, were drifting away from ancient traditions. The Bais Ya’akov answer was the creation of a new women’s Jewish educational system that, in its heyday, offered girls a seven-year curriculum that included prayers, the Bible, and Jewish laws and customs, taught primarily in Yiddish. Secular subjects were also offered as required by Polish law.

The American Shulamith group agreed with Schenirer’s assumptions and believed that, in this secularized country, yeshivah education for girls was essential. They differed, of course, over the ideological messages to be proffered. As Mizrachiites, they wanted, above all, for students to be inculcated with the love of Hebrew and of Zion, teachings that the Agudists disdained.

Some years later, with the approach of World War II, in 1937, the Bais Ya’akov girls’ yeshivah movement put down roots in Brooklyn’s hospitable Orthodox soil. And with its Yiddish-based, anti-Zionist Jewish ideology, its provision of only minimal general studies, and its pedigree as having merited the approbation of the great Torah sages of Eastern Europe, it quickly became one of the most favored organizations of the Agudath ha-Rabbanim and other comparable resistant Orthodox organizations. Still, when these American-based groups backed the Bais Ya’akov concept, they tacitly admitted that modern conditions necessitated that girls and young women in America receive a more extensive Jewish education than had their mothers and grandmothers.

Meanwhile, Mizrachi influences were strongly apparent and unchallenged in the mission and outlook of the Yeshivah of Flatbush, founded in 1927, and at the Ramaz School in Manhattan and the Maimonides School of Brookline, Massachusetts, both established in 1937. These first coeducational modern yeshivahs in the United States emphasized to girls and boys both the importance of modern Hebrew studies and culture even as they disdained the Talmud-predominant or Talmud-exclusive curriculum that had characterized earlier boys’ yeshivahs in this country and put a high premium on Orthodox accommodation to the secular world. Eventually, in the 1940s, as both the Mizrachi- and Agudist-influenced schools and their first students matured, each of these institutions added high-school programs to their offerings. Until that time, if New York Orthodox girls wanted training beyond elementary school under their denomination’s auspices, they had only the supplementary Hebrew Teachers Training School for Girls, sponsored by the women’s branch of the Orthodox Union. That is, of course, if these ambitious youngsters did not opt for pedagogic studies at the more established Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary of America, a school that welcomed both men and women.

Still, in all, through the interwar period, intensive Orthodox Jewish education remained the preserve of an elite, usually New York–based, group of women who had access to these schools. For most Orthodox women, both in the city and elsewhere, the synagogue, and specifically the synagogue sisterhood, was the locus of their public Orthodox Jewish lives and the source of their education and communal participation. Sisterhood educational and social activities were expanded dramatically for a middle-class female constituency that had time to devote to religious volunteer work. Women were told that they had a role to play and a particular talent in improving the aesthetic beauty of the sanctuary. And sisterhood classes were the place where many adult women acquired the Jewish knowledge that had been withheld from them as youngsters. Moreover, with the help of materials often produced by the national Women’s Branch of the Orthodox Union, major attempts were made to convince women that observance of commandments that they were learning about could be consonant with good middle-class life-styles. For example, pamphlets and books that spoke of the importance of Jewish women maintaining Term used for ritually untainted food according to the laws of Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws).kosher kitchens advocated for the faith on the basis that “nothing has refined the Jewish character as much as the dietary laws,” that “abstinence from foods permitted to others... develop[s] and strengthens self mastery and control,” and of course builds strong, healthy youngsters (Joselit, NY’s Jewish..., p. 110). The observance of laws of family purity (menstrual restrictions) was projected as contributing to family happiness, mental health, and beauty. And maybe as important, efforts were made to build beauty parlor–like modern ritual facilities that made purification more attractive.

What was done by, with, and for women as part of the modern Orthodox synagogue remained circumscribed within their own “special sphere,” the sisterhood. There, women assumed leadership roles and demonstrated their abilities and commitments. They were not part of the synagogue’s overall governance structure. Even the most avant-garde interwar synagogues emulated neither the example of the Jewish Endeavor Society nor of Harlem’s Congregation Mikveh Israel, which when founded in 1905 admitted two women to its original board of directors. However, it seems that Orthodox women of this period were not overly perturbed by their absence from the congregation’s power base. As one historian of interwar Orthodoxy has pointed out, “the guidebooks of the Women’s Branch of the Orthodox Union” do not evidence “even a hint of implied criticism or demurral” about the “special sphere.” Middle-class Orthodox women and men apparently agreed that in the end, women’s “chief characteristic was that of ‘homemaker’” and their “overriding objective in life was to beautify the Jewish home “(Joselit, “The Special Sphere...,” p. 223).

Educational opportunities for women under Orthodox auspices grew enormously in the postwar period as the varying styles of day school or yeshivah schooling for girls and boys became an expanding norm within that community. For those within the resisting segment, made up now primarily of those who had fled Hitler or survived the Holocaust, the Bais Ya’akov schools offered a curriculum that bolstered adherence to Old World ways and consciously underplayed the importance of general education. By 1948, it was possible for a young woman to stay within that educational system from elementary school through high school and through the seminary. At that most advanced level, the best and most committed students were offered their own Hebrew teachers’ training course, essential for that movement to produce its next generation of instructors. Significantly, their teacher certification did not mandate a college degree. Quite to the contrary, Bais Ya’akov women, like their brothers in old-line yeshivahs, were actively discouraged from entering that world of higher secular education. By the early 1960s, seminary graduates were running some sixteen Bais Ya’akov elementary and secondary schools and seminaries in New York and two sister schools outside the metropolis. Complementing the Bais Ya’akov system that attracted religious girls of all types were those smaller A member of the hasidic movement, founded in the first half of the 18th century by Israel ben Eliezer Ba'al Shem Tov.Hasidic girls’ yeshivahs, like Lubavitch’s Beth Rivkah schools, that were controlled by the specific groups that established themselves in postwar America.

Of course, girls’ yeshivahs were comparable to yeshivahs for boys and men primarily in their common goal of socializing their students against the perceived evils of general society. For example, as noted above, neither group of school leaders wanted their students to attend college. However, their Jewish educational missions were fundamentally different, befitting their adherence to Old World views of what Jewish men and women had to know. The ideal male student was the one most proficient in Talmud. Since the entire thrust of yeshivah training had always been to produce Talmudic scholars, that highly valued goal had to be continued in America. Women, on the other hand, were not to be taught Talmud since ordinarily they had not been exposed to such advanced learning in the past. And, in the minds of many Orthodox rabbinical leaders, it was at best a useless endeavor, at worst an evil pursuit. Practically, that meant that female yeshivah graduates were restricted to the types of studies their female ancestors were exposed to—with Bible being the most advanced subject—although they learned their Torah with greater intensity and sophistication.

The different ways these young men and women spent their long educational days had its own significant impact within these separatist communities. Freed from, or denied, the burden or opportunity of studying Talmud all day, female yeshivah students became more exposed to their American environment. Typically, these women emerged from school worldlier than their fathers, brothers, and, maybe most important, their husbands, a change that had no small impact upon how the sexes related to one another within their communities.

Meanwhile, in very different, third-generation Americanized Orthodox communities, coeducational schools flourished as the groundbreaking Flatbush, Ramaz, and Maimonides models were emulated nationally. By the early 1960s, there were some 90 coeducational schools and ten high schools under Orthodox auspices throughout the United States. In these institutions, girls and boys studied general subjects together and in some schools learned religious studies, including Talmud, in co-ed groups. After high school, girls and boys, possessed of prep school-level secular training, were expected to pursue American professional careers as that group increasingly found acceptance and felt comfortable in gentile environments.

In these same postwar years, the model of women’s education, first seen in the Shulamith School, was very attractive, in its own right, to Orthodox young women whose families identified with Yeshiva University. Although Yeshiva pioneered a comprehensive modern yeshivah educational system for men, it paid, through 1945, scant attention to the needs of Orthodox Jewish women. As early as 1928, it was possible for a male student to receive a quality, Talmud-intensive Jewish education, and more-than-adequate secular academic training, through his college years under one Orthodox roof. And if he then wanted to complete his schooling with Rabbinic ordination semikhah (ordination), as a modern Orthodox rabbi, he could finish his studies within Yeshiva’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS). There was no comparable girls’ high school or Orthodox college and certainly no rabbinical training school available for female counterparts. During the interwar period, daylong Jewish education for girls was only beginning, for a small elite, at the elementary school. The typical female counterpart of a yeshivah boy went to the public schools, and the most committed, among those who were lucky enough to live in New York, availed themselves of advanced supplementary Jewish training through high school at either the Conservative seminary or the Orthodox Union’s Hebrew Teachers Training School.

Yeshiva officials were sometimes criticized for their myopia toward young women. As early as 1925, one outspoken editorialist in the Orthodox monthly, the Jewish Forum, called upon the school “to submerge our prejudiced views of former days... let us think of our children, girls as well as boys—we regret that Dr. Revel (RIETS’ president) seems to make no provision for the Jewish education of our girls” (Gurock, The Men..., pp. 190–191). Nonetheless, such criticisms had no discernible effect upon Yeshiva’s policy makers because there was no significant demand for separate but equal training for young women emanating from its constituent families.

Most parents of Yeshiva’s students believed that their daughters could handle, as they always had, the social pressures and the sometimes anti-Jewish sentiments that were expressed in the religiously heterogeneous public schools. And as far as college was concerned, there was no need for a women’s Yeshiva College, established in 1928, because the overwhelming majority of Orthodox families did not consider postsecondary education a necessary, or even a warranted, final educational step for their daughters.

After World War II, Yeshiva University moved to provide Orthodox women with advanced educational opportunities largely because the women in their community and their families were then beginning to attend college. The first step toward the creation of an Orthodox women’s college was the establishment in 1948 of the Central High School for girls in Manhattan. Several years later, a Brooklyn branch was opened. In 1952, Yeshiva University absorbed the Orthodox Union’s Hebrew Teachers Training School as its own Teachers Institute for Women. Finally, in 1954, Stern College for Women began making its singular contribution to Orthodox women’s education.

From a social and religious ideological perspective, Stern, like Yeshiva College before it, affirmed a secular college education as permissible, indeed as warranted, for American Orthodox Jews. It also said to its prospective women, as Yeshiva had always said to its men, that they could imbibe much of the best of American college social life without challenge to their patterns of Orthodox observance. And it suggested to these women’s families that Stern’s particular niche included preparation for careers, graduate study, and “management of a Jewish home and family.” Implicit too was the understanding that this women’s college, placed within the world’s largest Jewish community, would provide its students, particularly those from smaller Jewish communities, with abundant opportunities for social engagements with potential marriage mates. From its inception, Stern College enrolled, in almost equal numbers, women from within and without the metropolitan area..

From a Jewish educational point of view, Central and Stern occupied a middle ground distinctive from Ramaz, Maimonides, and Flatbush and from Bais Ya’akov, even as the women’s college was flexible enough to attract a minority of students from these very different types of schools. For example, Talmudic study was always available as an option for students. And in the last two generations, Talmud has become increasingly popular, certainly among its college-age students. As an Orthodox, single-sex school, Stern’s classes were always closed to men, although many of their faculty members were males, as were its first three deans. In 1977, a Stern alumna, Karen Bacon, was appointed dean.

1970s-Present

By the 1970s, there emerged from among the many graduates of these girls’ yeshivahs, seminaries, and day schools and Stern College for Women a coterie of highly educated and motivated women destined to make a significant impact upon their variegated community. At the same moment, the resisting segment within Orthodoxy benefited from the work of women dedicated to upholding traditional ideas and the status quo. For example, learned women writers for the Lubavitcher movement articulated counterattacks against Jewish feminists’ calls for change within Orthodox Judaism. Some of these spokeswomen also engaged in discussions and debates on college campuses in furtherance of their movement’s outreach programs to unaffiliated Jews.

Meanwhile, other women, products of Orthodox day schools and then secular university training or Stern College, or sometimes defectors from Bais Ya’akov schools, challenged the Orthodox community to address what they perceived to be disabilities imposed upon them by halakhah and to accord them a greater role in synagogue life and public Orthodox ritual. Often defining themselves as Orthodox feminists and attuned to the rhetoric and successes of their sisters elsewhere, they saw no place for a “special sphere” within congregational governance, explored the ways in which women might participate in the Orthodox service within the bounds of Jewish law, demanded that Orthodox rabbis revisit the laws and consequences that govern the Woman who cannot remarry, either because her husband cannot or will not give her a divorce (get) or because, in his absence, it is unknown whether he is still alive.agunah (a woman who has been denied a Jewish divorce by her husband and is thus unable to remarry within Jewish law) and ultimately pressed for women to have professional religious leadership positions

Accordingly, in the 1970s-1980s, many modern Orthodox congregations changed, without profound religious debate, their long-standing rules governing membership and board leadership. Since century-old exclusions were rooted primarily in political custom and social mores and not Jewish law, it was a relatively simple matter to accommodate what women and some men wanted. In most instances, it was only a question of whether other men in the synagogue would be comfortable with women in positions of lay power within the congregation.

At the same time, the successful efforts of women to forward their participation within the Orthodox service provoked immense discussion and debate within Orthodox ranks. Unquestionably, the Hebrew Institute of Riverdale (Bronx, New York) was, and continues to be, the nation’s most avant-garde congregation in its championing of women’s involvement. There, with the expressed imprimatur of its rabbi, Avraham [Avi ] Weiss, beginning in the 1970s, worshipers regularly passed the Torah scroll from the men’s to the women’s sections during services. The parents and siblings of bar and Lit. "daughter of the commandment." A girl who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbat mitzvah children stood together on the Lit. "elevated place." Platform in the synagogue on which the Torah reading takes place.bimah during services to offer a family blessing. Women and men recited the Lit. "scroll." Designation of the five scrolls of the Bible (Ruth, Song of Songs, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther). The Scroll of Esther is read on Purim from a parchment scroll. megillah at special egalitarian readings on Purim.

Then, in the 2010s, under the initiative of Rabbi Steven Exler, who, in 2015 succeeded Weiss as Senior Rabbi of the Hebrew Institute and in close association with Rabba Sara Hurwitz, the congregation instituted additional opportunities for women to participate in service activities. As of 2019, women ascend the bimah to return the Torah to the ark and on The Jewish New Year, held on the first and second days of the Hebrew month of Tishrei. Referred to alternatively as the "Day of Judgement" and the "Day of Blowing" (of the shofar).Rosh Ha-Shanah men and women, standing within their respective sides of the mehitza are accorded the honor of calling out the notes of the Ram's horn blown during the month before and the two days of Rosh Ha-Shanah, and at the conclusion of Yom Kippur. Shofar-blowing ceremony. Beginning during Weiss’ tenure, women present learned sermons and other words of Torah on a weekly basis. On The Day of Atonement, which falls on the 10th day of the Hebrew month of Tishrei and is devoted to prayer and fasting.Yom Kippur Tisha B’Av, women have led the reading of elegies (kinot). It is also noteworthy that when a man is called to the torah, he is now encouraged to be called by both his mother’s and father’s name.

Meanwhile, since the 1970s, this synagogue has been home to a monthly women’s tefillah, which begins its year’s calendar with women’s hakafot (Torah procession) and a Torah reading during Lit. "rejoicing of the Torah." Holiday held on the final day of Sukkot to celebrate the completing (and recommencing) of the annual cycle of the reading of the Torah (Pentateuch), which is divided into portions one of which is read every Sabbath throughout the year.Simhat Torah. As of 1996, the Riverdale Women’s tefillah was one of thirteen such prayer groups that met regularly in synagogues and homes in the metropolitan area. Seven other groups met in other communities across the United States. It was estimated that college campuses were then home to an additional eight prayer groups. By 2004, there were 33 women’s tefillah groups in the United States, 22 of which were in New York, as well as 57 additional prayer groups in cities around the world.

However, by that time, there were those from within the women’s tefillah cohort who often, with their spouses, began developing more egalitarian Orthodox partnership minyans where men and women shared the liturgical duties. Drawing inspiration from initiatives first hatched in Jerusalem, at these services, which meet on Sabbath and holidays, at women lead the recitation of psalms [psukei d’zimra] that begin the service, men conduct the central shacharit and mussaf services. Women may take the Torah out of the Ark before the weekly Torah portion begins and they return the Scroll at the conclusion of the Torah reading. The actual chanting of the Torah is divided between men and women and either a woman or a man chants the haftarah (Prophetic portion of the week). Throughout these religious activities men and women sit and stand on their respective sides of the mechitza. As of 2019, there were an estimated 31 such services in ten states and the District of Columbia.

While varying types of public bat mitzvah experiences have widely become part of the contemporary Orthodox girl’s coming of age within almost all segments of the community, the majority of Orthodox congregations have neither accepted nor integrated most Orthodox feminist activities or groups into their synagogues’ lives. Indeed, as early as 1982, women’s tefillahs were castigated by both the Agudath ha-Rabbanim and by a group of five roshei yeshivah (teachers of Talmud) at Yeshiva University’s Orthodox seminary (RIETS). Leaders of old-line Orthodoxy in the United States told Orthodox feminists and their supporters, “Do not make a comedy out of Torah” (Gurock, American Jewish Orthodoxy..., p. 61). Three years later, in 1985, colleagues of Rabbi Weiss and Rabbi Saul Berman—another spokesman for feminist Orthodoxy within the Yeshiva University community—unequivocally declared that prayer groups were a “total and complete deviation from tradition” (Wertheimer, A People, p. 133). (Weiss left the Yeshiva faculty in 2000 soon after he founded Yeshivat Chovevei Torah. As of 2019, Berman remains on the Yeshiva University faculty.) In all events, this resistant oppositional position continues to the present day. For example, in 2013, the Rabbinical Council of America, an organization made up primarily by men ordained by RIETS and under the sway of its roshei yeshivah, made clear that it opposed partnership minyans (Wertheimer, The New, 155). Spokesmen for the Agudath ha-Rabbanim and their brother associations have uniformly expressed antipathy to what they see as a deviant development.

On another communal front of importance to women, and arguably to many men as well, in Jerusalem in 1990, under the leadership of Rabbanit Chana Henkin, a program was established to train women to serve as Yoatzot Halacha (halakhic guide). Nishmat, now known as the Jeanie Schottenstein Center for Advanced Torah Study for Women, has provided its students with a classic halakhic and Talmudic curriculum, with supplementary instruction in women’s medicine, to qualify women to answer questions on Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah niddah and sexual and fertility issues. Since 1999, its graduates have served communities all over the world. In 2004, Bracha Rutner was engaged as the first Community Yoetzet Halacha in the United States at the Riverdale Jewish Center. Soon thereafter, Shayna Goldberg began working in Teaneck and Englewood, New Jersey, followed by Atara Eis in Silver Spring, Maryland. As of the end of 2019, there were seventeen women employed as Yoatzot Halacha in 51 institutions in 22 communities in the United States and Canada.

This institutional innovation has been seen favorably by many otherwise resistant rabbinical authorities, not so much as the acceptance of a feminist demand but rather as a formalizing, with additional scientific training and sophistication, of an essential communal function that in the past was often carried out by the wives of Orthodox rabbis who ministered to the women in their communities.

Concomitantly, there has been widespread interest among Orthodox rabbis of many stripes in addressing and ameliorating the long-standing and tragic predicament of the agunah (chained women). Since 1981, Agunah Inc. founded by Orthodox feminists Rivka Haut and Susan Aranoff, has been in the forefront of applying necessary social pressure to advance this cause within their own community. The battle has been engaged on two fronts. In some individual cases and communities, pulpit rabbis and communal leaders have excoriated men who have refused to grant their wives the necessary writ of divorce that would permit them to resume normal lives and social relationships. These efforts have received mixed reviews among Orthodox feminists, who want their rabbis and men’s organizations to ostracize recalcitrant husbands more aggressively. Various religious legal remedies have been explored to bend halakhic rules appropriately. Their solutions have ranged from prenuptial agreements to ex post facto annulments of marriages. In 1993, the Rabbinical Council of America, the national organization of Orthodox rabbis made up primarily of men ordained by Yeshiva University, approved an innovative prenuptial document. Since that critical approbation, this document has become well-nigh de rigeur at weddings conducted by accommodating Orthodox rabbis. There has, however, been some resistance within other segments of the Orthodox rabbinate to this procedure.

Finally, as of 2019, the area of greatest conflict between resisting and accommodating segments of the Orthodox community was the question of consummate female religious leadership: serving as rabbis. Rabbi Weiss once again paved the way in 1997 when he appointed Sharona Margolin Halickman as a “congregational intern” at his Riverdale synagogue. She was soon promoted to a staff position as its madricha ruchanit (spiritual guide.) In both posts, she basically performed the educational and pastoral duties that young male rabbinic interns fulfilled but stopped short of rendering any halakhic decisions. Halickman remained in that post for seven years before moving to Israel. In 2004, Sara Hurwitz took over in her stead. Most Orthodox rabbis did not support Weiss’ moves and some were highly and vocally critical of his activities. Yet he did have the backing of Rabbi Yitz Greenberg and Blu Greenberg, two of the staunchest supporters of Orthodox feminism. Both, for years, had been outspoken about the possibility and eventuality of women earning Orthodox ordination in the United States.

The moment in time that Weiss, the Greenbergs, and those men and women who shared their point of view had hoped and planned for and their opponents feared and vigorously opposed took place on March 22, 2009, when Weiss and Rabbi Daniel Sperber ordained Hurwitz as a “Maharat” (Leader of Jewish Law, Spirituality and Torah). Six months later, under Weiss’ initiative, Hurwitz began bearing the title “Rabba”—effectively a distaff rendering of the title “Rabbi.” Although Hurwitz—and for that matter Weiss—immediately and continually absorbed withering attacks from Orthodox opponents, she, with Weiss’s assistance, has proven to be an effective Orthodox feminist institution builder. Indeed, in the same year as Hurwitz’s conferral, she became the founding Dean of Yeshivat Maharat, a school that “ordains women with semikha so they may serve Jewish communities as fully credentialed spiritual and halakhic leaders” (yeshivatmaharat.org). As of 2019, the institution has ordained 33 women who carry the titles of “Rabba,” Rabbanit,” “Maharat,” “Darshanit,” and “Rabbi.” The school permits its graduates to choose their clerical designation. These religious leaders, along with the some 21students then in the program, served more than 50 communities nationwide in synagogues, schools, and Hillels. Opposition to “women rabbis” remains robust. In February 2017, for example, the Orthodox Union, the largest congregational association of Orthodox synagogues in the United States, issued a statement barring women from serving as clergy in synagogues. This organization has, however, frequently affirmed the role women must play as educators and scholars within the Orthodox community. Undoubtedly, the issue of women’s religious leadership is destined to continue to roil Orthodox Judaism in the United States.

Dushkin, Alexander M. Jewish Education in New York City (1918).

Fine, Jo Renee, and Gerard Wolfe. The Synagogues of New York’s Lower East Side (1978).

Furstenberg, Rochelle. “The Flourishing of Higher Jewish Learning for Women.” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 429 (May 1, 2000).

Goldman, Karla. Beyond the Synagogue Gallery: Finding a Place for Women in American Judaism (2000); Farber, Seth. An American Orthodox Dreamer: Rabbi Joseph D. Soloveitchik and Boston’s Maimonides School (2004).

Grinstein, Hyman B. The Rise of the Jewish Community of New York, 1654–1860 (1945).

Gurock, Jeffrey S. American Jewish Orthodoxy in Historical Perspective (1996), and The Men and Women of Yeshiva: Higher Education, Orthodoxy and American Judaism (1988), and Ramaz: School, Community, Scholarship and Orthodoxy (1989), and When Harlem Was Jewish (1979).

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. New York’s Jewish Jews: The Orthodox Community in the Interwar Years (1990), and “The Special Sphere of the Middle-Class American Jewish Woman: The Synagogue Sisterhood.” In The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed, edited by Jack Wertheimer (1987).

Lerner, Anne Lapidus. “‘Who Has Not Made Me a Man’: The Movement for Equal Rights for Women in American Jewry.” AJYB 77 (1977): 11–16.

Poll, Solomon. The Hasidic Community of Williamsburg (1962).

Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Aaron. The Silver Years in American Jewish Orthodoxy: Rabbi Eliezer Silver and His Generation (1981).

Sarna, Jonathan D. “The Debate over Mixed Seating in the American Synagogue.” In The American Synagogue: A Sanctuary Transformed, edited by Jack Wertheimer (1987).

Sussman, Lance. Isaac Leeser and the Making of American Judaism (1995).

Wertheimer, Jack. A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America (1993).

Women’s Tefillah Network Newsletter (August 1996).