Conservative Judaism in the United States

Women have played a pivotal role in Conservative Judaism throughout the 20th and 21st centuries and have been instrumental on both the grassroots and national levels in propelling the Conservative Movement to confront essential issues including Jewish education, gender equality and religious leadership. Strong female leaders and constituents have challenged the Movement to continue to adapt to an ever more egalitarian world, while maintaining rootedness in tradition and halakhah (Jewish law). The Conservative Movement’s attention over the decades to issues such as the religious education of Jewish girls, the status of the agunah (deserted wife), equal participation of women in ritual, the ordination of women, and innovations in liturgy and ritual to speak to women’s experiences has helped to shape the self-definition of Conservative Judaism and its maturation as a distinct denomination.

Women have played a pivotal role in Conservative Judaism throughout the 20th and 21st centuries and have been instrumental on both the grassroots and national levels in propelling the Conservative Movement to confront essential issues including Jewish education, gender equality, and religious leadership. The Conservative Movement’s attention over the decades to issues such as the religious education of Jewish girls, the status of the agunah (deserted wife), equal participation of women in ritual, the ordination of women, and innovations in liturgy and ritual to speak to women’s experiences has helped to shape the self-definition of Conservative Judaism and its maturation as a distinct denomination.

Women’s Roles as Rebbetzins and in Sisterhoods

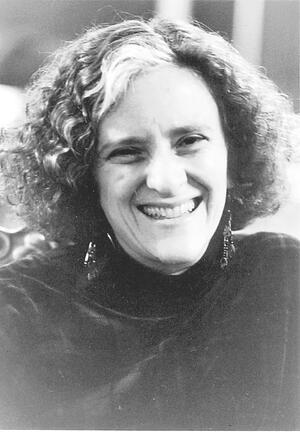

Mathilde Schechter.

Courtesy of CJ: Voices of Conservative/Masorti Judaism.

Solomon Schechter, president of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) (1902–1915), and his wife, Mathilde Schechter, were convinced of the indispensability of Jewish homemakers to the preservation of Judaism in the United States. After her husband’s death, Mathilde Schechter extended their vision by founding the National Women’s League (now the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism) in 1918 as the women’s division of the United Synagogue of America. Through this organization, which is the coordinating body of Conservative synagogue sisterhoods, the Conservative Movement has promoted the perpetuation of Conservative Judaism in America and the Masorti Movement worldwide via the home, synagogue, and community.

Mathilde Schechter believed in setting a personal example of Jewish living and was a powerful role model, especially for Jewish Theological Seminary faculty wives and rebbetzins (rabbis’ wives) who in turn influenced others. Rebbetzins have served as important role models and experts for their congregants. They opened their homes for Sabbath and holidays, teaching by example the beauty of Jewish observance. Some served as guides to fledgling sisterhoods by supervising committees and programs, delivering divrei Torah (brief talks on religious topics), and writing bulletin columns. They were particularly valuable in the area of The Jewish dietary laws delineating the permissible types of food and methods of their preparation.kashrut, setting communal standards through their own home kitchens and teaching others the minutiae of keeping a kosher home.

The Conservative Movement experienced rapid growth in the interwar and post–World War II periods. During that time, congregational sisterhoods formed the backbone of the educational mission of the Conservative synagogue. Rabbis generally depended on these women for their loyal support of educational programming. Sisterhood women successfully took on many projects that greatly enhanced Conservative Jewish life in their synagogues, offering financial support as well as volunteer hours. They often took responsibility for assisting in Sunday and religious schools and were instrumental in organizing classes in Jewish living and observance for mothers. Typically, women also maintained the synagogue kitchen, both by ensuring kashrut and by serving as cooks and hostesses for the collations and luncheons that were the hubs of synagogue activities. Many groups also took it upon themselves to issue a sisterhood cookbook, a popular fund-raising project that demonstrated on a local level that it was possible to keep the highest standards of kashrut while cooking a wide variety of both Jewish and American-style dishes. Maintaining the synagogue gift shop, women were largely responsible for introducing Jewish ceremonial objects, as well as Jewish books and artwork, into the homes of Conservative Jews. Finally, these women were often instrumental in campaigns to decorate or refurbish synagogue buildings. Choosing curtains, carpeting, and wall hangings, women often set the tone for their synagogue through their dedication to its beautification.

The National Women’s League provided inspiration on a national level for each of these local efforts through its publications and its leadership. For example, Betty Greenberg and Althea Osber Silverman shared their views on the beauty and spirituality of the Jewish home with other American Jewish women in “The Jewish Home Beautiful,” a pageant first presented in the Temple of Religion of the World’s Fair in 1940 and then published as a popular book by the National Women’s League. Althea Osber Silverman with her Habibi and Yow and Sadie Rose Weilerstein with her K’tonton series became noted children’s authors who made it easier for mothers to enrich their children’s Jewish upbringing by providing adventurous, age-appropriate stories on Jewish customs and festivals. The combined efforts of all these women reinforced the message that one could both embrace American culture and transmit a full Jewish life to one’s children. Through their writings, as well as through their lives, these women reassuringly demonstrated that Conservative Jewish living was compatible with the aspirations of upwardly mobile women.

Over the years, synagogue sisterhoods have developed programs to nurture modern Jewish women’s educational and spiritual growth. Many contemporary sisterhoods sponsor classes for women interested in reading Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah or leading prayers, workshops in which they fashion their own tallitot (prayer-shawls) or are guided in how to don tefillin (phylacteries), or special programs for Rosh Chodesh (the celebration of the New Month) that may involve meditation, yoga, or other spiritual practices. While for years many Conservative synagogue have devoted one SabbathShabbat a year to highlighting the sisterhood’s activities and members, Sisterhood Shabbat (or Women’s League Shabbat, as it is referred to in some synagogues) is now more likely to feature women as leaders and participants in all aspects of the shabbat services. Women’s League, too, working to enhance the engagement of 21st-century women with Jewish texts, conducts remote programs, such as an eighteen-month study of the entire tractate of Mishnah Berakhot, taught by women rabbis affiliated with Conservative/Masorti Judaism.

Historically, many women found sisterhood provided a space in which to develop and realize leadership within a synagogue community that was generally administered by men. Eventually, however, some women moved up the ranks of synagogue administration from sisterhood to congregational leadership positions, where they have played active roles as officers of congregations throughout the United States and Canada. Currently nearly half of the congregations affiliated with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ) are led by female synagogue presidents.

The National Women’s League also played a crucial role in the national Conservative scene through its fund-raising capabilities. Through its yearly Torah Fund campaign, Women’s League was responsible for collecting sufficient funds to open the Mathilde Schechter Residence Hall—the first JTS dormitory to house women—and, later for refurbishing what is now called the Women’s League Seminary Synagogue. Funds raised by these women made an important difference in the quality of life for students at the Jewish Theological Seminary. In addition to its continued support of JTS in New York, Torah Fund of Women’s League currently supports projects in each of the Conservative/Masorti Movement’s other affiliated educational institutions: the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies (Los Angeles, CA), Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem), Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano (Buenos Aires, Argentina), and Zacharias Frankel College (Potsdam, Germany).

Women’s Status and Issues of Equality in Conservative Judaism

Several difficult Jewish legal issues have long perplexed rabbinic leaders concerned about the inequality of women. The most difficult of these is that of the agunah, a woman whose husband has left her without issuing a Jewish divorce. She is unable to remarry as a result. The longstanding concern for the agunah is an important sign of the Conservative Movement’s commitment to addressing the unequal treatment of women. The Law Committee tried for over 20 years to resolve the dilemma, and the first breakthrough came with the adoption of what came to be known as the “Lieberman clause” (developed in 1953 by Talmudist and Conservative The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhicdecisor Rabbi Saul Lieberman [1898–1983], who served as both dean and rector of the Jewish Theological Seminary), which made the Jewish marriage contract into a binding civil agreement that committed both husband and wife to abide by the recommendations of a Jewish court of law if their marriage ended. Though widely used throughout the Conservative Movement, it did not resolve the agunah problem. First, many rabbinic authorities hesitated to bring Jewish legal matters to the civil courts. Second, the civil courts have been reluctant to decide religious questions, even in states like New York that have laws prohibiting one spouse from impeding the remarriage of another. Therefore, the Joint Bet Din (Jewish court) of the Conservative Movement has, in recent years, become more aggressive in dealing with this problem, both by certifying Conservative rabbis qualified to write gittin (bills of divorce) and by using hafka’at kiddushin (annulment of marriage) as a tool against recalcitrant husbands. Based on a Talmudic text, though not universally accepted, hafka’at kiddushin is reserved for those severe cases where a Jewish divorce cannot be obtained, either because of the husband’s extreme recalcitrance or his disappearance. The Joint Bet Din deals with each case individually and, where necessary, grants approval for a local Bet Din to annul the marriage. This approach has protected and aided women beyond what the Lieberman clause accomplished without abandoning a commitment to Jewish legal principles. Additionally, the Conservative Movement’s Rabbinical Assembly (RA) has accepted the use of pre-nuptial agreements stipulating the requirement of a get (Jewish divorce) should the marriage be dissolved.

The Conservative Movement has long advocated equal education for both sexes, calling for primary Jewish education for girls at a time when girls traditionally were receiving little formal Jewish instruction. Similarly, on a more advanced level, the Teachers Institute of the Jewish Theological Seminary, founded in 1909, offered Jewish higher education to men and women on an equal basis. From 1915 on, it also offered a professional teacher-training curriculum that enabled women to prepare for careers in Jewish education.

The path of women from the periphery to the center of religious life began with the introduction of mixed seating in prayer services. By 1955, mixed seating characterized the overwhelming majority of Conservative congregations and served as a yardstick to differentiate them from Orthodoxy. The Bat Mitzvah, first introduced by Mordecai M. Kaplan in 1922 for his own daughter, Judith Kaplan (Eisenstein), became increasingly popular within the Conservative Movement. By 1948, approximately one-third of all Conservative synagogues had introduced such a ceremony. Bat mitzvah took different forms, including group rituals that resembled confirmation as well as individual ceremonies at the late Friday evening service, where the bat mitzvah girl generally chanted a haftarah. By the 1980s, most bat mitzvah ceremonies came to resemble a Lit. "son of the commandment." A boy who has reached legal-religious maturity and is now obligated to fulfill the commandmentsbar mitzvah, with girls being called to read from the Torah and chant a haftarah. A 1995–1996 survey of Conservative synagogues reported that 80% gave identical treatment to bar and bat mitzvah celebrants. The rapid growth of the bat mitzvah ceremony was also designed as an incentive to retain girls in the same supplementary religious school educational setting as boys. The Conservative Movement was challenged to accept the implications of this equality in education and obligation in places like Camp Ramah as well, where girls were given the opportunity to assume leadership roles in prayer services.

In 1955, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards (CJLS) of the Conservative Movement responded to the changing role of women in the synagogue by deciding to permit women to be called up for aliyot (the honor of being called to the Torah). At that time, the option was implemented in only a few synagogues in the Minneapolis area, but the precedent was established. In 1973, the CJLS passed a takkanah (enactment) that allowed women to count in a The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan equally with men. One year later, it adopted a series of proposals that equalized men and women in all areas of ritual, including serving as prayer leaders. Also in 1973, the United Synagogue of America, the Conservative Movement’s congregational association, now called the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism (USCJ), resolved to allow women to participate in synagogue rituals and to promote equal opportunity for women for positions of leadership, authority, and responsibility in congregational life. Between 1972 and 1976, the number of Conservative congregations giving aliyot to women increased from seven percent to fifty percent.

Grassroots pressure for change intensified throughout the 1970s. In 1972, Ezrat Nashim, a group of young, well-educated women, most of whom were products of the camps and schools of the Conservative Movement, presented to the RA a call for the public affirmation of women’s equality in all aspects of Jewish life. They demanded that women be granted membership in synagogues, counted in a minyan, allowed full participation in religious observances, recognized as witnesses in Jewish law, allowed to initiate divorce, permitted and encouraged to attend rabbinical and cantorial school and perform as Rabbis and Cantors in synagogues, encouraged to assume positions of leadership in the community, and considered bound to fulfill all the mitzvot (commandments) equally with men. While this call evoked a sympathetic response from the rabbinate, it precipitated widespread, often heated, divisive debate within the Conservative Movement and in the press over the following decade.

The Movement to Ordain Women as Rabbis and Cantors

Some women who wanted to become Conservative rabbis came to study at the seminary, and due to an unrelated academic reorganization effective with the 1974–1975 year, they were able to study in any class at their appropriate level. Preparing for ordination without being officially enrolled in the rabbinical school, they hoped that someday they would be ordained on the basis of their studies. In September 1977, the seminary’s chancellor, Gerson D. Cohen, appointed a Committee for the Study of the Ordination of Women as Rabbis, which held hearings in cities throughout the country to obtain the perspective of the laity as well as the view of its professionals. The committee’s final report of January 30, 1979, recommended, 11 to 3, that women be ordained, but the RA voted 127 to 109 to take no action prior to the decision of the seminary faculty. Pressure increased when, one month later, seminary students formed GROW (Group for the Rabbinical Ordination of Women) in an attempt to organize political action and education. In 1979, the issue was brought to the seminary senate for a vote, but it was tabled when its divisiveness became apparent.

In 1983 the RA decided to consider for membership Beverly Magidson, a graduate of Hebrew Union College, the Reform Movement’s seminary. Her admission fell short of receiving the necessary three-quarters vote of rabbis present but had widespread support, an indication that such approval was imminent. This spurred JTS to reconsider the issue, and on October 24, 1983, the seminary faculty voted 34 to eight, with one abstention and over half a dozen absent in protest, to admit women to the seminary’s rabbinical school. The Jewish legal basis for their acceptance was the Halakhic decisions written by rabbinic authories in response to questions posed to them.responsum of Rabbi Joel Roth (known as the Roth Teshuvah), which held that individual women could become rabbis (and prayer leaders) if they chose to assume the same degree of religious obligation as men. Individuals opposed to the decision formed the Union for Traditional Conservative Judaism, which became a separate group in 1990, changing its name to the Union for Traditional Judaism.

The first class to include women entered the seminary in the fall of 1984 and Amy Eilberg was the first woman ordained (1985). At the spring 1985 convention, the RA voted to admit for membership Beverly Magidson and Jan Kaufman, also a graduate of Hebrew Union College. Their membership was made effective July 1, 1985, to enable Eilberg, the seminary graduate, to be the first woman admitted to the RA. By 1997, there were 72 women members of the RA out of a total membership of almost 1400. This included several in Israel and one in Latin America. By 2004, that number had reached 177, about eleven percent of the total membership. As of 2020, female rabbis make up 20 percent of RA memberships, with female-identified rabbis comprising 24 percent of North American Conservative rabbis working in the field. Women rabbis also have become active members in the CJLS, influencing not only the discourse around issues of Jewish law but also the choice of topics taken up by the committee, including appropriate mourning rituals for women suffering a miscarriage or stillbirth. As of 2019 the CJLS has a female co-chair.

Women’s presence in the rabbinical schools has had a dramatic impact on the nature of rabbinic education. Enrollment in the Rabbinical School at JTS averages about an equal split between male- and female-identified students (there are gender non-binary and trans students enrolled as well). This ratio is generally also born out at the Zeigler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles; founded as an independent rabbinical school in 1996, Zeigler is the other Conservative-affiliated rabbinical school in the United States. Women have also become more prominent in the faculty, administration, and leadership of these institutions. The inclusion of women’s voices in the classroom—as students and professors—has added a diversity of perspectives to rabbinic training in a myriad of ways. Moreover, history was made in May 2020 when historian Dr. Shuly Rubin Schwartz was selected to serve as the Chancellor of JTS—the first woman head in the seminary’s 134-year history.

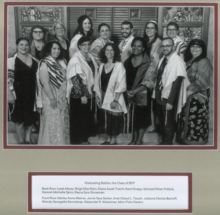

The struggle for acceptance of women as cantors took a different course. Since its inception in 1952, the Jewish Theological Seminary’s Cantorial School/College of Jewish Music (now the H.L. Miller Cantorial School) had accepted women to its degree programs in sacred music; however, only men were eligible to study simultaneously towards a diploma in hazzanut. In 1987, Chancellor Ismar Schorsch announced that the seminary would confer the diploma of Synagogue cantorhazzan on two women, Marla Barugel and Erica Lippitz. The Cantors Assembly (CA) voiced its disapproval and established a Committee of Inquiry to look into the question of admitting women. A resolution to admit women to the CA was defeated in 1988 (95 for, 97 against) and again in 1989 (108 for, 82 against, 2 abstentions) and 1990 (110 for, 68 against); although the majority of the assembly had turned in favor of admission, the resolution failed to receive the necessary two-thirds vote. Women were finally admitted in December 1990 as a result of a decision by the executive council of the assembly. In 1997, 38 of the 476 members of the CA were women (about eight percent); by 2017 women comprised about one-third of its membership. Today women make up about half of the student body in the H.L. Miller Cantorial School. Cantor Nancy Abramson, who in 2013 was elected the first female president of the CA, is presently the Director of both the cantorial school and the Women’s League Seminary Synagogue.

The Roth Teshuvah guided the seminary synagogue until 1995, when Chancellor Schorsch announced that in the Women’s League Seminary Synagogue the principle of full egalitarianism would be decisive in granting women religious status equal to that of men. Some students agitated for liturgical change as well, challenging the Conservative Movement to address issues of sexism and patriarchy in the liturgy. Responsive to these types of challenges, the Conservative Movement’s prayer book, Siddur Sim Shalom, first published in 1985, which is utilized in the seminary synagogue and in the vast majority of Conservative synagogues, provides for the optional inclusion of the matriarchs along with the patriarchs in the main Lit. "standing." The primary element of each of the three daily prayer services.Amidah prayer. While the Women’s League Seminary Synagogue is fully egalitarian, it leaves the inclusion of the matriarchs to the discretion of each day’s prayer leader.

The Impact of Female Clergy on the Conservative Movement

After nearly four decades in the rabbinate and cantorate, women have made an undeniable impact on the Conservative Movement; women occupy pulpits throughout the United States and even in Israel. While over the years there has been an increasing acceptance of women clergy by Conservative congregations, the road has not been without its challenges. Given the RA seniority system of placement for rabbis, women began to become eligible for positions in large congregations only in the 1990s. Debra Newman Kamin was the first woman to serve as senior rabbi of a major Conservative congregation, Am Yisrael, in Northfield, IL (1995). The 2005 hiring of Rabbi Francine Roston to lead Congregation Beth El, in South Orange, NJ, marked the first time a woman would serve as senior rabbi in a Conservative synagogue of more than 500 families.

These issues came to the fore in August 2004, when the RA released the results of a survey it had commissioned of women in the Conservative rabbinate, entitled “Gender Variation in the Careers of Conservative Rabbis: A Survey of Rabbis Ordained Since 1985.” The survey found that women rabbis were paid less and occupied far fewer senior or full-time positions: 83 percent of women pulpit rabbis surveyed led congregations of fewer than 250 families, seventeen percent led congregations of 250–499 families, and none led congregations larger than 500 families. Conversely, nearly all—91 percent—declared themselves to be uninterested in holding a senior rabbinical post at a large congregation. At the time, RA leadership presumed that, although the nature and challenges of rabbinic leadership were essentially the same for all rabbis, women were generally more concerned about quality-of-life issues—in terms of their families and private lives—and were more likely to make adjustments in their careers for the sake of those concerns. However, after the results of the survey were published, Movement leadership committed to ensuring that those women who would choose to lead large congregations had the opportunity to do so. This issue, however, reemerged nearly fifteen years later, as it became clear that inequities remained, and that, in fact, women rabbis were faced with certain gender-specific challenges in their rabbinate.

The survey also discovered “very unusual family patterns among female Conservative rabbis,” noting that female rabbis were three times more likely to be single than their male counterparts, with a total of 58 percent of those surveyed found to be either single or childless. Many women in the Conservative rabbinate were not surprised by this finding. Some posited that certain men might find dating a female rabbi intimidating or threatening. Others theorized that Conservative women rabbis may be caught in a “catch-22”; like their male counterparts, Conservative women rabbis are likely to be more observant than their congregants, and so seek mates who share their high level of observance. But women rabbis must also seek partners who are not so traditional that they reject egalitarianism—or the possibility of marrying a woman rabbi. Today, sources at the RA point to a greater likelihood for both female- and male-identifying rabbis to be single than they were decades ago.

Today’s women rabbis and cantors are no longer the novelty they once were. As more women have entered these fields, their presence has become less noteworthy and more normative. Moreover, the rabbinate itself has changed, with assumptions for what comprises a successful rabbinic career (for rabbis of any gender) shifting radically. With the number of Conservative congregations shrinking, and thus fewer available pulpits, many more rabbis (approximately 46 percent) are pursuing careers in non-pulpit settings. Furthermore quality-of-life issues hold more weight with this generation of rabbis, with a perceived shift in importance from both male- and female-identified rabbis toward a better work-life balance, which is difficult to achieve in pulpit work. Concurrently there is a move away from using pulpit-size as a barometer of success, not only for rabbis in the field but even within the RA placement office itself. While the culture at large has clearly influenced this evolution—especially now, with dual-income homes becoming more common—the presence of women in the rabbinate (and among RA administration) over the past decades has no doubt changed perceptions as well.

The Conservative Movement, like other Jewish and secular institutions, has not been immune from the impact of the #MeToo movement that began to gain traction in 2017/2018. Accounts of sexual harassment (both verbal and physical), bullying, unwanted physical contact, and otherwise improper behavior, endured by women rabbis and cantors over the years at the hands of colleagues and congregants, were brought to light in the groundswell response to #MeToo. In addition, employment discrimination—pay disparity between men and women and more limited access to senior positions—remains a challenge, according to reports from female clergy in the field. In 2019, under the leadership of then RA president, Rabbi Debra Newman Kamin, the RA formed a Me Too Task Force to help the longstanding RA Vaad Hakavod (Ethics Committee) adapt to the complexities of the #MeToo era. Transitioning the task force into the new (as of summer 2020) Gender and Power Committee, the RA is taking a proactive approach: reexamining policies and procedures—both disciplinary and supportive—and ensuring that rabbis are educated on current culturally acceptable norms and practices. The RA is taking steps to promote a sensitive, safe, and supportive work environment for 21st-century rabbis of any gender identification.

Egalitarianism and the Conservative Synagogue

At its convention in 1992, the RA adopted a resolution calling for Gender Equality in Halakhah (Jewish law). It encouraged all branches of Conservative Judaism to support full equality of all Jews, regardless of gender, in every area of religious and community life, and urged the CJLS to address issues of continued gender inequity in its responsa, specifically in regard to the prohibition of women serving as witnesses and as judges in rabbinic courts. Subsequently several responsa were submitted that offered possible ameliorations for the issue of women as edim (witnesses). Due to the nature of the Conservative Movement, which leaves the final decision to the individual rabbi to rule on particular interpretations of Jewish law for his/her congregation, and due to the varying congregational cultures across the United States, there continue to be variations in how gender equity is applied in the congregational setting. However, since the ferment of those final decades of the 20th century, the vast majority of Conservative synagogues have become fully egalitarian. Although the official position of the Conservative Movement is to endorse both egalitarian and nonegalitarian services, and both options continue to be offered at the seminary, United Synagogue events, and some Ramah camps, it is estimated that fewer than 20 of the 600 USCJ member congregations are considered nonegalitarian.

Conservative women have come of age religiously, entering the mainstream of public Jewish religious life. Ceremonies for the naming of baby girls, once performed in an ad hoc, experimental way by individual families, are now commonplace, facilitated by the publication of National Women’s League’s Simhat-Bat: Ceremonies to Welcome a Baby Girl (1994). It is now commonplace to see women reading Torah and donning Jewish religious garb for prayer. Over the past 40 years, a substantial number of Conservative women have begun to wear tallitot (prayer shawls) and a smaller number also lay tefillin (phylacteries); in fact, there is now generally no difference in the introduction of these mitzvot to both boys and girls in preparation for becoming b’nai mitzvah. The ubiquity of women’s adoption of these mitzvot as norms has influenced the marketplace, with feminine-styled tallitot and kippot (skullcaps) available in Judaica shops worldwide. Boys and girls in the Conservative Movement now receive the same Jewish education, empowering women with the Jewish knowledge necessary to become equal and active participants in synagogue services and other elements of religious life.

Taken as a whole, then, the Conservative Movement took great strides during the 20th century in positioning itself to enter the 21st century committed both to Jewish law and to gender equity. While challenges remain in applying the ideals of equality in a culture that sometimes fails to live up to its highest values, the Conservative Movement has emerged strengthened and keenly dedicated to maintaining a fulfilling and vibrant Jewish life for all of its adherents.

Abramson, Nancy. Personal correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, July 2020.

Cantors Assembly Minutes, 1987–1991.

Cardin, Nina Beth, and David W. Silverman, eds. The Seminary at 100. New York: United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, 1987).

Cohen, Steven M. and Judith Schor. “Gender Variation in the Careers of Conservative Rabbis: A Study of Rabbis Ordained Since 1985,” July 14, 2004.

Fishman, Sylvia Barack. A Breath of Life: Feminism in the American Jewish Community. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 1993.

Friedman, Reena Sigman. “The Politics of Ordination.” Lilith 6 (1979): 9–15.

Geller, Myron S. “Woman is Eligible to Testify.” CJLS (HM35:14.2001a) https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/assets/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19912000/geller_womenedut.pdf.

Greenberg, Simon, ed. The Ordination of Women as Rabbis: Studies and Responsa. New York: JTS Press, 1988.

Grossman, Susan, and Rivka Haut, eds. Daughters of the King: Women and the Synagogue. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1992.

Heilman, Uriel. “When Rabbis Say #MeToo.” Hadassah (June 2019) https://www.hadassahmagazine.org/2019/06/27/rabbis-say-metoo/.

Heilman, Uriel. JTA, August 10, 2004.

Hyman, Paula E. “The Introduction of Bat Mitzva in Conservative Judaism in Postwar America.” YIVO Annual 19 (1990): 133–146.

JTS Website, “JTS Appoints Dr. Shuly Rubin Schwartz as Institution’s Eighth Chancellor,” (June 1, 2020) http://www.jtsa.edu/jts-appoints-dr-shuly-rubin-schwartz-as-chancellor.

Joselit, Jenna Weissman. The Wonders of America: Reinventing Jewish Culture, 1880–1950. New York: Hill & Wang, 1994.

Nadell, Pamela S. Conservative Judaism in America: A Biographical Dictionary and Sourcebook Greenwood Press, 1988.

National Jewish Population Survey. Council of Jewish Federations. 1990.

Nevins, Daniel. Personal correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, July 2020.

Rabbinical Assembly. Correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, July 2020.

Siegel, Seymour, ed. Conservative Judaism and Jewish Law. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1977.

Sklare, Marshall. Conservative Judaism: An American Religious Movement. Rev. ed. New York: Schocken, 1972.

Stone, Amy. “Gentleman’s Agreement at the Seminary.” Lilith (Spring/Summer 1977): 13–18.

Tigay, Chanan. JTA, March 10, 2005.

United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. Correspondence with Helene Herman Krupnick, July 2020.

Wertheimer, Jack. A People Divided. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 1993.

Wertheimer, Jack, ed. The American Synagogue. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, 1987.

Wertheimer, Jack, ed. Jews in the Center: Conservative Synagogues and their Members. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000.

Women’s League for Conservative Judaism Website. Accessed July 27, 2020. https://www.wlcj.org.