Sarah Schenirer

"Frau Schenirer, we are not merely placing a memorial on your grave site. We are placing it upon our hearts: for us, and for all the generations who will come after us." Bais Ya’akov students and teachers from around the world attended the 2005 re-dedication ceremony of Sarah Schenirer’s gravestone, and with these words, the director of the Central Bais Ya'akov in Jerusalem eulogized the woman to whom all had come to pay their respects.

Institution: Devorah Sandorfy Sabag, Jerusalem

Sarah Schenirer was a divorced dressmaker who, in 1917, founded a school in her studio in Krakow, seeking to provide Orthodox girls with a religious education and thus stem the tide of religious defection. The school grew into a network of schools called Bais Yaakov and in 1923 came under the auspices of Agudat Israel, the political organization of world Orthodoxy. Her 1933 Gizamelte shriftn (Collected Writings) was advertised as “first sefer (religious book) by a modern woman.” Schenirer remarried near the end of her life but had no children. Bais Yaakov girls in her lifetime and afterward called her “Our Mother Sarah,” and she continues to be venerated and commemorated by the movement she founded.

As the founder of the Bais Ya’akov educational movement, Sarah Schenirer brought about a revolution in the status of women in Orthodox Judaism.

Early Life and Education

Schenirer was born on July 3, 1883, in Kraków, Poland, the third of nine children of Bezalel and Rosa (Lack) Schenirer; the Schenirers were a distinguished rabbinic family with ties to both Belzer and Sandzer Hasidism. But the environment in which she was raised was rapidly secularizing, and several of her eight siblings and many of her friends abandoned Orthodox observance. The crisis of defection was especially acute among girls; girls were generally sent to non-Jewish schools, where they imbibed a love for secular culture, while their brothers were protected from such influences by being enrolled in yeshivas. Schenirer herself attended a Polish public school through eighth grade and loved Polish and German literature and theater. Unlike most of her peers, however, she combined these interests with an intense devotion to Jewish Orthodoxy, nourished by the Yiddish religious texts her father provided her. Her environment, though, provided few outlets for girls and women to express their religious interests, and she envied her brothers the opportunities they had for Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah study and Hasidic pilgrimage. All these aspects of her personality set her apart from other girls and women around her, and she earned the pejorative nickname of “Hosidke” [little A member of the hasidic movement, founded in the first half of the 18th century by Israel ben Eliezer Ba'al Shem Tov.hasid, or little pious one] when she was still young.

Bringing Orthodox Women Back to Observance

After she left school, Sarah Schenirer found work as a seamstress and dressmaker, but she continued her education by voraciously reading both Jewish and secular texts, attending public lectures, and frequenting the Polish theater. Her Polish diary records that by 1909 or so, she had begun harboring what she herself saw as an eccentric and persistent dream, to bring her “Orthodox sisters” back to passionate observance. Her first marriage in 1910, to Shmuel Nussbaum, broke up after three years in part because her husband had no patience for these aspirations. She was known by her maiden name during the years after her divorce.

Schenirer found support not in her immediate environment, where Orthodox authorities neglected the religious lives of young women, but in Vienna, where she relocated as a refugee at the outbreak of World War I. There, she was inspired by a neo-Orthodox rabbi, Rabbi Moshe David Flesch (1879-1944), who was a follower of the teachings of the founder of German neo-Orthodoxy, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888). One of Rabbi Flesch’s sermons, describing the glorious role women had played in Jewish history, allowed her to imagine how she herself might inspire Polish Orthodox women. Upon her return to Kraków in 1915, Schenirer founded a club and library for the young women of her community, her attempt at an Orthodox alternative to the vibrant secular culture of youth movements and popular adult education of Kraków.

Founding Schools for Orthodox Girls

Schenirer’s initial attempts were only partly successful: while the young women were inspired with the religious ideas she transmitted in her lectures, they were not interested in taking on Orthodox observance. Given these difficulties, Schenirer decided to found a school for young girls. At her Hasidic brother’s suggestion, she sought a blessing for her endeavor from the Belzer Rebbe (Issacher Dov of Belz, 1854–1927) at his lodgings in Marienbad; the Rebbe wished her blessings and success, thus giving his sanction to the endeavor. He may not have understood precisely what she was proposing, since he later forbade his Hasidim from sending their daughters to her school.

In 1917 Schenirer set up a kindergarten, finding the pupils among the daughters of her customers. According to some versions of this founding story, she began with 25 pupils, which according to gematria (the numerical values of Hebrew letters) has the same value of the first word in the biblical verse “KO tomar le-veit Yaakov” (“Thus shall you say to the house of Jacob …” [Exodus 19:3]), at the very beginning of the story of the giving of the Torah on Sinai. The name of Schenirer’s school system, Bais Yaakov, or House of Jacob, thus connected her enterprise with the A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrashic understanding of women as having been present at Sinai, even as having received the Torah first. In its name and through similar strategies, the Bais Yaakov movement found ways to ground its innovative experiment within Jewish tradition.

A Growing Movement

The movement grew with extraordinary speed, at first under Sarah Schenirer’s sole leadership, and within a few years under the larger institutional umbrella of the new political organization of world Orthodox Jewry, Agudath Israel. Agudath Israel resolved at its First World Congress in 1923 to support and administer Sarah Schenirer’s school system, which had grown to dozens of schools by that time. Many Hasidic groups and other stringently Orthodox leaders considered Bais Yaakov too radical a departure from traditional practices, or worried that a school that drew a diverse student population would lead to the lowering of the strict standards that were upheld in their own circles. Rabbi Avraham Meir Alter (1866-1948), of Gur, however, one of the founders of Agudath Israel, was a strong supporter of the movement. Bais Yaakov drew many students from Gur and other Hasidic groups, but it also attracted girls from Lithuanian Orthodox families, and indeed from a broad spectrum of religious and even secular families.

By the mid-1930s, the system had grown to more than 300 schools throughout Europe and a budding system in New York and Palestine. Bais Yaakov also included a journal, a publishing company, youth movements, summer camps, three teachers’ seminaries, and a distinctive religious culture by and for girls and young women, influenced not only by German neo-Orthodoxy, Eastern European Hasidism, and the yeshiva, but also by socialism, feminism, Yiddishism, and other secular ideologies of the period. In discovering and reviving “old-new” Jewish rituals for women, Sarah Schenirer created “kosher” substitutes for the secular nature clubs and youth movements of her milieu, as well as female variations on the Hasidic and yeshiva experiences that had excluded her as a woman.

Sometime around 1930, Schenirer remarried, to Rabbi Yitzhak Landau. They had no children together. In 1933, Schenirer’s Gizamelte Shriftn (Collected Writings) was published by the Bais Yaakov Press, advertised and acclaimed as “the first sefer [religious text] written by a modern woman.” That same year, she stepped down from the directorship of the Kraków Teachers’ Seminary but remained the symbolic head until her death.

Schenirer died of cancer on March 1, 1935, at the age of 51. By the time of her death, Sarah Schenirer, a divorced seamstress with no formal degrees or status in either the religious or secular realm, had seen her dream embodied in a worldwide movement crediting with rescuing Orthodoxy at a moment of great peril.

Legacy

Schenirer’s charisma and the legends of the founding of Bais Yaakov not only continued after her death but perhaps even increased, with the trauma of the Holocaust and the continuing flourishing of the school system. Bais Yaakov girls everywhere consider themselves “daughters” of Sarah Schenirer, “Mame Sore” or “Sarah Imeinu”—Our Mother (or Matriarch) Sarah.

In 2001, during a pilgrimage to Kraków convened by the Sara Schenirer Commemorative Committee of Agudah Women of America, a Hebrew and English commemorative plaque was placed on the building that had housed the Teachers’ Seminary. Two years later, a cadre of women set out to restore Schenirer’s tombstone, razed along with other Jewish tombstones when the Plaszow concentration camp was built. A large contingent of Bais Yaakov students and teachers from the United States and Israel traveled to Poland to attend the rededication ceremony. The director of the Central Bais Yaakov in Jerusalem eulogized Sarah Schenirer, saying: “Frau Schenirer, we are not merely placing a memorial on your grave site. We are placing it upon our hearts: for us, and for all the generations who will come after us.”

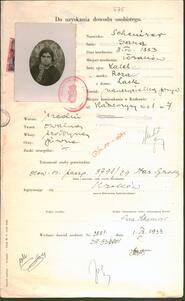

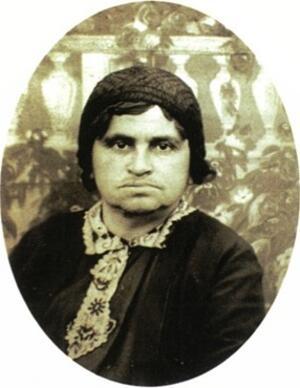

In 2005, the seventieth anniversary of Sarah Schenirer’s death, between 500 and 1000 students and graduates came to Poland from Israel, North America, and throughout Europe to pay their respects at her grave; that same year, an archival repository was established at the Central Bais Yaakov in Jerusalem to document the early history of the Bais Yaakov movement. Schenirer had refused to be photographed during her lifetime, and the only extant photo of her is an application for an ID card. But numerous women, including Holocaust survivors who had attended the first Bais Yaakov schools, contributed both memories and mementos towards the establishment of the Bais Yaakov historical society. Pilgrimages to the Teachers’ Seminary and to Sarah Schenirer’s gravesite in Kraków and commemorations of her yahrzeit (anniversary of her death) around the world continue as part of Bais Yaakov culture until the present day.

Bais Yaakov Project, dedicated to the collection, preservation, and digitization of historical material related to the Bais Yaakov movement from its founding in 1917 through today. https://thebaisyaakovproject.com/

Baumel, Judith Tydor, and Jacob J. Schacter. “The Ninety-Three Bais Yaakov Girls of Cracow: History or Typology.” In Reverence, Righteousness, and Rahamanut: Essays in Memory of Rabbi Dr. Leo Jung, edited by Jacob J. Schacter. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, 1992.

Benisch, Pearl. Carry Me in Your Heart: The Life and Legacy of Sarah Schenirer. New York: Feldheim Publishers, 2003.

Dansky, Miriam. Rebbetzin Grunfeld: The Life of Judith Grunfeld, Courageous Pioneer of the Bais Yaakov Movement and Jewish Rebirth. Rahway, NJ: Mesorah Publications, 1994.

Leibowitz, Rebbetzin Danielle S. with Devora Gliksman. Rebbetzin Vichna Kaplan: The Founder of the Bais Yaakov Movement in America. Brooklyn, NY: Keter Judaica, 2016.

Lisek, Joanna. “Orthodox Yiddishism in Beys Yakov Magazine in the Context of Religious Jewish Feminism in Poland.” In Ashkenazim and Sephardim: A European Perspective, edited by Andrzej Katny, Isabela Olszewska, and Aleksandra Twardowska. Pieterlen and Bern: Peter Lang, 2013.

Rubin, Devora, comp. Daughters of Destiny: Women Who Revolutionized Jewish Life and Torah Education. Rahway, NJ: Mesorah Publications, 1988.

Seidman, Naomi. Sarah Schenirer and the Bais Yaakov Movement: A Revolution in the Name of Tradition. Liverpool: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2019.

Weissman, Deborah. “Bais Ya’acov: A Historical Model for Jewish Feminists.” In The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives, edited by Elizabeth Koltun. New York: Schocken Books, 1976.

Weissman, Deborah R. “Bais Ya’acov, A Women’s Educational Movement in the Polish Jewish Community: A Case Study in Tradition and Modernity.” Master’s thesis, New York University, 1977.

Zolty, Shoshana Pantel. “And All Your Children Shall Be Learned”: Women and the Study of Torah in Jewish Law and History. Lanham, MD: Jason Aronson, 1997.