EL Konigsburg

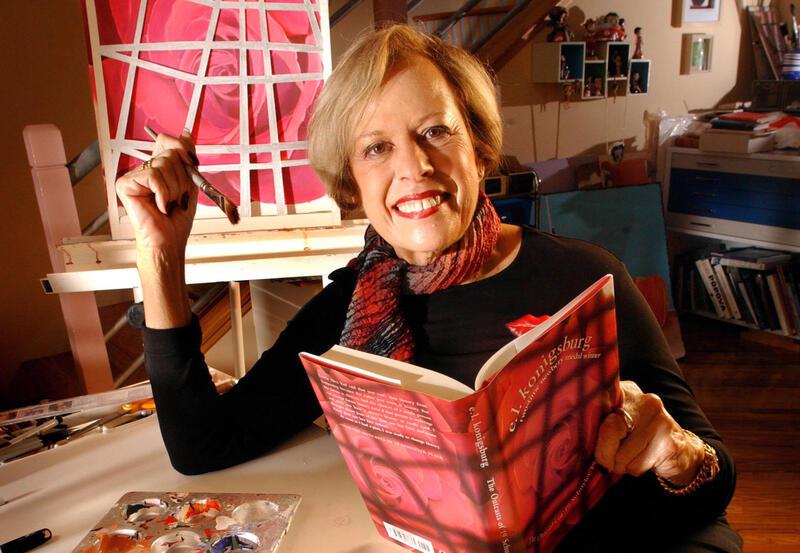

E.L. Konigsburg, the daughter of working-class Hungarian Jewish parents, had to figure out early on how to create her own opportunities. Only after her three children were in school did she begin to write the children’s books that made her beloved. Her first, Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and me, Elizabeth, emerged from watching her daughter hesitantly discover new friends in a new school; her second, From the Mixed-Up Files of Ms. Basil E. Frankweiler, is about two siblings who run away from their Connecticut suburb and live in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She was the only author to have two books on the Newberry Award list at the same time: From the Mixed-Up Files won the Newberry in 1968, the same year Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth was a runner-up.

Introduction

Some people think small-town life is a curse. Everything there is limited—opportunities, choices, chances. In school, children can’t study some subjects that their city cousins might, and they may not have teachers who are as well prepared. They may feel isolated, and if they don’t have many friends, it’s tough and lonely. But some people see opportunities in growing up in a small town. A bright child may find ways to study or learn on their own, particularly if a public library is nearby, and may find other opportunities to seize.

That’s what E.L. Konigsburg did, and it took her far: two Newberry Medals, and the devotion of fans the world over—readers far from the small Pennsylvania town where she was raised.

Elaine Lobl Konigsburg, known professionally as E.L. Konigsburg, is remembered by many people who grew up with her beloved novels: The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler; About the B’nai Bagels; Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth, or any of her other novels. Konigsburg’s novels and her characters reflect the angst of growing up in a middle-class world and finding your way, no matter where you come from.

Early Life & Family

Konigsburg, born in New York in 1930, moved with her family to a series of small towns in Pennsylvania and had to figure out very early on how to create her own opportunities, because nobody was going to show her the way. Her parents were working-class people of Hungarian Jewish heritage who ended up in a mill town north of Pittsburgh where her father owned a bar. With three daughters, the parents worked hard: Elaine and her sisters wore clothes sewn by her mother.

No one in the family seemed to care about anything that did not involve the activities of daily living, so Elaine found, quite early, that if she wanted to read—and she did—she would have to do it by the light of a bare lightbulb in the only bathroom in their apartment above the bar. She hid in the bathroom at night and read books such as The Secret Garden and Mary Poppins. If a particularly sad passage moved her to tears, she would flush the toilet to keep her parents from hearing her crying. But not all of it was “good” literature. She later told the Saturday Review that “I have no objection to trash. I’ve read a lot of it and firmly believe it helped me hone my taste.”

Even though Konigsburg was valedictorian of her high school and editor of the school newspaper, she had no guidance counselors to help her figure out what to do about college, and she had no money to pay for tuition. She decided to apply to the chemistry program at Carnegie Institute of Technology. To pay for one year’s tuition, she worked as a bookkeeper for a local meat company for a year after graduating from high school. There she met David Konigsburg, her future husband, a relative of the owner.

In her freshman year at Carnegie Mellon, Konigsburg took a required English Composition course taught by a new instructor, Dr. A. Fred Sochatoff. A short man with a huge heart hidden behind a rather formal style, he proved to be a very important link to her future. This man and this class changed her life, although she didn’t know it at the time.

In the spring of her freshman year, Konigsburg was walking on the Cut, a grassy walkway down the center of campus, when she encountered her teacher. “Miss Lobl,” Sochatoff said, “what are your plans for the summer and what courses have you selected to take for your sophomore year?” Konigsburg, who had not confided in anyone at college about her financial straits, said she would have to drop out and work for a year to earn money for her second year in college. To which Dr. Sochatoff replied, “Miss Lobl, a student of your ilk cannot be allowed to drop out. Let me see what I can do.”

Dr. Sochatoff consulted with his wife, whose sister-in-law was a well-known community leader in Pittsburgh. Together they were instrumental in securing financial aid for Konigsburg’s sophomore year. She supplemented the scholarship funds by managing a dormitory laundry and working as a playground instructor, a waitress, and a library page. With this help she was able to graduate with honors in 1952. As Konigsburg said, “I worked hard and did well. However the artistic side of me was essentially dormant.”

But the die had been cast. As Dr. Sochatoff’s daughter, Dr. Mildred Sochatoff Myers, remembers, Konigsburg became part of the Sochatoff family. After Dr. Sochatoff died in 1987, “Millie” kept in touch with Konigsburg until Elaine’s death in 2013. Konigsburg herself expressed her relationship with Dr. Sochatoff better than anyone else; when she received a Distinguished Alumna Award from Carnegie Mellon University in 1999, she said, “The only course in writing I have ever had was Freshman Composition, taught by Dr. A. Fred Sochatoff. One of my books is dedicated to him. It says: For Fred Sochatoff—who was there at the. beginning, before either of us knew it was a beginning. Dr. Sochatoff and I had both arrived….when the school was under the Carnegie Plan. We students were to be taught how to solve problems. In Freshman Composition that translated into being taught how to explain or describe difficult processes or concepts in a straightforward manner. And in our literature course, we were taught how to interpret the bells and whistles but not write with them. To this day I cannot think of any better training for any writer.”

Marriage & Early Career

In July 1952, Elaine married David Konigsburg, who had become an industrial psychologist. From 1952 to 1954 Konigsburg worked as a research assistant in a tissue culture laboratory while a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh. After moving to Jacksonville, Florida, in 1954, she taught science at a private girls’ school. After having three children, Paul, Laurie, and Ross, she resumed teaching at the girls’ school from 1960 to 1962. While staying home with her children, she pursued painting, a foreshadowing of the artistic bent that inspired her to illustrate most of her books.

In 1962 David Konigsburg was transferred to New York, and the children were enrolled in school. Konigsburg began to write!

The inspiration for Konigsburg’s first novel came from watching her daughter Laurie hesitantly discover new friends after moving to suburban New York. The book was Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and me, Elizabeth. It tells the story of Elizabeth, who is new in town, and her attempts to find friends. It doesn’t help that she is small for her age. Cynthia, the cool kid in school, is quick to dismiss her. But Elizabeth meets Jennifer, another classic outsider who styles herself as a witch and is Black. Elizabeth soon becomes her apprentice, and suddenly life is full of adventures.

From this first novel, critics saw that this author didn’t look for easy solutions. Elizabeth comes face-to-face with what it means to be “normal” and decides it doesn’t matter, that it’s better to be yourself—a profound and timeless insight. Interestingly, Konigsburg isn’t writing about her early life but rather thinking about her daughter. Or is she also thinking about herself? She leaves you to wonder.

Growing Literary Fame

After a few years in various New York suburbs, Konigsburg and family returned to Florida. In the late 1960s, now a Jacksonville housewife with no agent, she mailed Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and me, Elizabeth to Atheneum Books. While waiting for its publication she began to write From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

From The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler is the story of Claudia and Jamie Kincaid, a sister and brother who run away from their Connecticut suburb and live in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. They end up in the house of the wealthy Mrs. Frankweiler, who cuts them a deal. As one of the characters puts it, “kids are amateur adults.”

Like the fictional Frankweiler, Konigsburg treated children with respect. Dr. Millie Socatoff Myers, recalls experiencing this characteristic when, as a teenager, she was invited to tea at Elaine’s home in Pittsburgh shortly after she was married. Elaine treated Millie “as the adult I so much wanted to be.” In all her novels, she took children seriously. Her own children would critique her work when they came home from school for lunch. Laughter would encourage her; glum faces meant she had to revise.

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler was published in 1967 and was awarded the 1968 Newberry Medal. In the same year, Konigsburg was a runner-up for that award for Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley and Me, Elizabeth. She was the only author to have had two books on the Newberry list at the same time. She later won the 1997 Newberry award for The View from Saturday. As Perry Nodelman noted in Dictionary of Literary Biography, “Konigsburg is an innovator and tireless experimenter, a creator of interesting messes. A truly artistic temperament at work, if one remembers her scientific training and artistic bent (she illustrated most of her novels).”

Jewish themes

Konigsburg’s third novel, About the B’nai Bagels, has an explicitly Jewish theme. And yet the characters and plot are a marvelous stew of ethnic Judaism, American sports culture, and universal observations on growing up and parenting. It’s poignant to note that Konigsburg dedicated this book to “My own dear mother, who knows almost nothing about baseball and almost everything about love and stuffed cabbage.”

Bessie, the mother in About the B’nai Bagels is making stuffed cabbage as the novel opens. Her older son, Spencer (who is 20 and a student at NYU), is showing his sophistication by telling her that he had gone to a famous Hungarian restaurant in New York that put raisins in the stuffed cabbage and why couldn’t she try that? “Raisins in stuffed cabbage? Never, Sauerkraut and a touch of sugar,” Bessie claims. Her son replies, “Bessie, you see that’s what’s wrong with you. You never try anything new. Your mind is closed.”

Bagels is narrated by Mark, Spencer’s (almost)13-year-old brother. Mark makes many remarkable observations on parenting, sibling relationships, pre-teen friendships, and baseball strategies. Part of the parenting piece involves Mark’s infatuation with a Playboy magazine and its playmate and his mother’s brilliant take on this, in contrast to the conventional reactions of his friends’ parents. The dialogue is hilarious and the messages timeless. One is left, though, with a big unanswered question: Did Mrs. Lobl put raisins or sauerkraut in her stuffed cabbage?

Remembrance

Konigsburg died following a stroke in 2013. One of the people who spoke at her funeral was Joseph Ellovich, a friend from high school days who remained close to her during her Florida years. His son was the model for Spencer, the B’nai Bagel character. He saw first-hand, at an early age, the bright mind, the inquisitive and observant spirit, the enormous determination to succeed that would serve Konigsburg well throughout her life. He also saw her after she had a stroke that left her aphasic and paralyzed on her right side. She showed him how she had learned to paint with her left hand and created a beautiful still life with flowers. She seized every opportunity to create something beautiful.

Selected Works by E.L. Konigsburg

Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley, and Me, Elizabeth. New York: Atheneum, 1967.

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. New York: Atheneum, 1967.

About the B’nai Bagels. New York: Atheneum, 1969.

A Proud Taste for Scarlet and Miniver. New York: Atheneum, 1973.

Throwing Shadows. New York: Atheneum, 1979.

The View from Saturday. New York: Atheneum, 1996.

Silent to the Bone. New York: Atheneum, 2000

The Outcasts of 19 Schuyler Place. New York: Atheneum, 2004

The Mysterious Edge of the Heroic World. New York: Atheneum, 2007.

Langer, Emily. "E.L. Konigsburg, author of 'From the Mixed-up Files of Mrs. Basis E. Frankweiler' and other children's classics, dies at 83." Washington Post, April 22, 2013.

Library of Author Biographies, 2006

Miller, Abigail. "Remembering E.L. Konigsburg" Tablet, April 23, 2013.

Myers, Mildred Sochatoff. "The Author E.L. Konigsburg had many ties to Pittsburgh." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 1, 2013

Telephone interviews with Joseph Ellovich, Burlington, Vermont, and Dr. Milddred Sochatoff Myers, Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University

Vitello, Paul. “E.L Konigsburg Author is Dead at 83." New York Times, April 22, 2013.