Roz Chast

Roz Chast is one of New York’s most distinct cultural voices, most famous for her New Yorker cartoons. Her works range from whimsical, irreverent, and quirky to poignant and heartbreaking, and her idiosyncratic oeuvre includes various collections of her works, several books for young children, and the widely acclaimed graphic memoir Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, an unsparing account of the travails of coping with the needs of her aging parents and their prolonged deaths. Dedicated to capturing the surreal nature of urban angst and its related neuroses, Chast’s signature visual language ranges from lively, sometimes frenzied drawings to serenely hued watercolors of cityscapes or, occasionally, rural life.

Introduction

Her works ranging from whimsical, irreverent, and quirky to poignant and heartbreaking, Roz Chast is widely considered one of the most comically ingenious and satirically edgy visual interpreters of everyday life. She is one of New York’s most distinct Jewish cultural voices, most famous for her New Yorker cartoons over the past four decades (over 800 cartoons as of 2022). Her idiosyncratic oeuvre includes various collections of her works, several books for young children, and the widely acclaimed graphic memoir Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, an unsparing account of the travails of coping with the needs of her aging parents and their prolonged deaths, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, was shortlisted for a National Book Award, and was one of the The New York Times 10 Best Books of 2014. Chast’s work expresses a distinctly Jewish sensibility, brimming with satirical fatalism and outsider humor but also persistent accentuations of resilience. There is a palpable sense that Chast’s postmodern cartoons ironically riff on earlier generations of immigrant Jewish maladjustments, insecurities, and angst. The results can be poignant and hilarious all at once.

As fellow cartoonist Liana Finck observes of the uneasy subjects of Chast’s art, her “disgruntled men; horrible storefronts; dumb, square-toothed horses; gourmandizing pigeons; bottom-of-the-barrel bourgeoisie in optimistic little hats—are, at their heart, about deeper things: loneliness, family, the impossibility of maintaining order, and the batshit, bonkers ridiculousness of life” (“Roz Chast,” Paris Review). While most closely associated with The New Yorker, Chast’s laugh-out-loud work has also frequently appeared in numerous other venues, including The Village Voice, National Lampoon, Scientific American, and Mother Jones. In addition to her numerous honors and awards, in 2012 she received the NYC Literary Honor in Humor by Mayor Bloomberg and was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2013.

Education and Early Success

Chast was born on November 26, 1954, in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn, NY, the only child of two educators (her mother Elizabeth was an assistant principal and her father George taught French and Spanish) who had known each other since the fifth grade. Her birth name, Rosalind, which she has never used, was inspired by the heroine of Shakespeare’s As You Like It. Chast’s grandparents on both sides were Russian Jews, and many of her relatives perished in the Holocaust. In Chast’s upbringing, Judaism was taken for granted; her father enjoyed speaking Yiddish and her mother belonged to both Hadassah and B’nai B’rith.

Chast began drawing at a very early age, and after studying painting and printmaking at Kirkland College in upstate New York, attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where she received her BFA in graphic design and painting in 1977. The latter was not an altogether happy experience; Chast has said that much of the time her works were ignored by teachers and peers alike, and she felt like an inferior artist.

Not long after graduating, Chast embraced a life of cartooning, and her first works appeared in the gay men’s magazine Christopher Street, National Lampoon, and The Village Voice. In 1978, when she was just 23, her first work for The New Yorker was accepted, a quirky drawing of imaginary objects called “Little Things” (the magazine’s Art Editor Lee Lorenz reportedly stunned Chast when he insisted that the young cartoonist should return weekly). Her work continues to appear there to this day.

In interviews, Chast has often described her early success as “very sudden and unexpected.” The macabre work of Charles Addams was an early acknowledged influence, perhaps contributing to her own mordant approach to the darker side of life. Other early sources of pleasure were the satirists of Mad Magazine. Chast was also drawn to the underground comics of R. Crumb. She always signs her work R. Chast (“not in honor of R. Crumb but not not in honor of him, either”). It is noteworthy that when Chast’s work first began to appear in The New Yorker in the 1970s, it expressed a young woman’s perspective of the world, not at all typical of the magazine’s cartoon content at the time. (It has been said that the magazine’s older generation of male cartoonists were not among her fans.) She was also one of the magazine’s first cartoonists to insist on using her own eccentric lettering, rather than their standard gag captions. In spite of her New Yorker fame, she has also collected hundreds of rejections from the magazine over the years.

Singular Style and Sensibility

Dedicated to capturing the surreal nature of urban angst and its related neuroses, Chast’s signature visual language ranges from lively, sometimes frenzied drawings to serenely hued watercolors of cityscapes or, occasionally, rural life. She draws with Rapidograph pens and later adds watercolor. The critic Adam Gopnik describes her distinctive style as consisting of “an imagery of limits and losers…quick, broken lines, spidery lettering, and much uneasy blank space.” Gopnik also claims that Chast’s “historical role” combines the “sophisticated humor of The New Yorker with the gawky, confessional truth-telling and boundary-crossing of graphic forms” and alternative comics (“Scenes from the Life”). Though filled with fury, fearful imaginings, neuroses, and various discomforts, her work is almost inexplicably approachable, and her subjects have an indelibly Everywoman appeal, perhaps due to the artist’s sheer comic inventiveness.

Perhaps most Chast admirers are drawn to her affectionate mockery of her subjects and would likely share her fellow New Yorker cartoonist Liza Donnelly’s acute observation that Roz’s “love for her characters” is palpable to an extent that “one feels reassured and joins in her affection. They are us, but not really. Roz keeps us in a complicated dance of relating to those she draws, while allowing us to keep our distance so we can laugh. It feels as though Roz’s drawings come straight from her psyche, uninterrupted. She is sharing her inner thoughts as they emerge, unedited. If one relates to what she is saying in her cartoon, it’s on an emotional level” (“Roz Chast”). Perhaps because of her capacity for channeling emotional and psychological depths, many perceive Chast’s sensibility as novelistic rather than conventionally humorous, visualizing and verbalizing the taboo and suppressed, the stress and chaos of the everyday.

Later Life and Works

Chast’s almost excruciatingly personal and undoubtedly most critically and commercially successful book, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? (2014), artfully blends cartoons, sketches, and photos, combining her finely tuned sense of absurdity with the exasperating and often traumatic difficulties of coping with her elderly parents’ struggles and her own guilty responses to their bewilderment, rage, dementia, falls, nurses, and hospitalizations in their final years. She had long portrayed her parents’ neurotic habits and travails (as well as her fraught relationship with them) in cartoons, even before her professional life, once remarking to an interviewer that she discovered from an early age that

they were funny. I think I knew them very well. And I liked drawing them. But when I drew those people that a lot of people think of as my parents I think they’re also not just my specific parents, but a certain kind of parent figure, you know? When I was younger I was very self-conscious of them because they were so different for so many different reasons from my friends’ parents…. My relationship with my parents was complicated for a lot of reasons. I am grateful to them and I love them and they also drove me bananas (Furio).

Chast’s father died at 95 and her mother at 97. In describing the memoir’s impact, comics scholar Tahneer Oksman asserts that it “ultimately presents its readers with the paradox of what it means to mourn those who had such a profound effect on you, even as they never fully grasped who you are and even as you never fully grasped who they were. Chast gets through the pain of looking back, of moving on, by comically targeting a world she doesn’t fully understand, the very world that cast her out before she became a shaper of her own.” Chast credits her inspiration in rising to the grueling challenge of portraying what happened to her parents to the achievements of earlier graphic memoirists, citing Art Spiegelman and Marjane Satrapi as influences who emboldened her approach. The acclaimed memoirist David Giffels celebrated Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? for both its candor and nuanced complexity and insistence on sacrificing neither the darkness nor light of human experience. Alex Witchel’s appraisal was also characteristic of the memoir’s effusive critical reception: “This is a beautiful book, deeply felt, both scorchingly honest about what it feels like to love and care for a mother who has never loved you back, at least never the way you had wanted, and achingly wistful about a gentle father who could never break free of his domineering wife and ride to his daughter’s rescue. It veers between being laugh-out-loud funny and so devastating I had to take periodic timeouts.”

Two years after Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? was published, the City Museum of New York, in collaboration with the Norman Rockwell Museum, hosted a special exhibition of over 200 images from this and other cartoon memoirs by Chast. Art critic Ken Johnson has praised these later works for their “soulfully wacky renditions of scenes from the surrealistic human comedy of modern life.” The success of her memoir was followed by three additional graphic novels—Going into Town (2017), an acerbic and affectionate book about how to spend one’s time in New York City, and two books of humor cowritten with Chast’s close friend and collaborator, Patricia Marx: Why Don’t You Write My Eulogy Now So I Can Correct It?: A Mother’s Suggestions (2019) and You Can Only Yell at Me for One Thing at a Time: Rules for Couples (2020). Chast and Marx are also musical collaborators in their ukulele band, Ukular Meltdown. In 2024, President Joe Biden presented Chast with the National Humanities Medal by President Joe Biden for "deepen[ing] the nation's understanding of the humanities and broad[ening] our citizens' engagement with history, literature, languages, philosophy, and other humanities subjects."

Today, much of Chast’s working life is structured around the intense weekly publication schedule at The New Yorker; typically she submits six or eight drawings a week for consideration, devoting the rest of her time to book manuscripts and other projects. Chast has a cherished collection of graphic novels and comics, as well as 300 volumes by New Yorker cartoonists, dating back to the earliest years. Her passions include klezmer music, playing the ukulele, and caring for her pet parrots and lorikeets (whose antics inspired the avian protagonist of her children’s books Too Busy Marco and Marco Goes to School).

Chast lives in the town of Ridgefield, Connecticut, and has been married to the humor writer Bill Franzen since 1984 (they met in The New Yorker offices). They have two adult sons.

To listen to Terry Gross’s Fresh Air Interview (December 30, 2014) with Roz Chast about her cartoon portrayal of caring for her aging parents during the last years of their lives in the memoir In Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, click here: https://freshairarchive.org/segments/cartoonists-funny-heartbreaking-take-caring-aging-parents

Selected Works

With Patricia Marx. You Can Only Yell at Me for One Thing at a Time: Rules for Couples. New York: Celadon Books, 2020.

With Patricia Marx. Why Don't You Write My Eulogy Now So I Can Correct It?: A Mother's Suggestions. New York: Celadon Books, 2019.

Going Into Town: A Love Letter to New York. New York: Bloomsbury, 2017.

Around the Clock. New York: Atheneum, 2015.

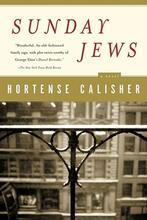

Can't We Talk About Something More Pleasant? New York: Bloomsbury, 2014.

What I Hate: From A to Z. New York: Bloomsbury, 2011.

Too Busy Marco. New York: Atheneum, 2010.

Theories of Everything: Selected, Collected, and Health-Inspected Cartoons, 1978-2006. New York: Bloomsbury, 2008.

The Party, After You Left. New York: Bloomsbury, 2004.

Childproof: Cartoons About Parents and Children. New York: Hyperion, 1997.

Proof of Life on Earth. New York: HarperCollins, 1991.

The Four Elements. New York: HarperCollins, 1988.

Mondo Boxo: Cartoon Stories. New York: HarperCollins,1987.

Last Resorts. New York: Ink Inc., 1979.

SELECTED AWARDS AND HONORS

- National Humanities Medal (2024)

- Induction into The Society of Illustrators Hall of Fame (2019)

- Annual Masters Series Award at the School of Visual Arts (2018)

- Cartoonist of the Year from the National Cartoonists Society (2015)

- Annual Heinz Award for the Arts and Humanities (2015) Rhode Island School of Design Alumni Award for Artistic Achievement (2017)

- Kirkus Prize (2014)

- Reuben Award (2014)

- Honorary doctorates from Dartmouth College (2011), Lesley University/Art Institute of Boston (2010), and Pratt Institute (1998)

Donnelly, Liza. “Roz Chast.” In “Roz Chast: Cartoon Memoirs.” Norman Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies Exhibition (2014): https://www.nrm.org/2015/03/roz-chast-cartoon-memoirs/

Finck, Liana. “Roz Chast, The Art of Comics.” The Paris Review 237, Summer, 2021: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/7816/the-art-of-comics-no-3-roz-chast.

Furio, Joanne. “An Interview with Roz Chast.” The Believer, Vol. 111, January 1, 2015: https://believermag.com/an-interview-with-roz-chast/

Giffels, David. “Reading Through Grief: 5 Books on Death and Mortality.” Literary Hub, January 3, 2018: https://lithub.com/reading-through-grief-5-books-on-death-and-mortality…;

Gopnik, Adam. “Scenes From the Life of Roz Chast.” The New Yorker, December 30, 2019: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/30/scenes-from-the-life-of-roz-chast

Johnson, Ken. “Why Roz Chast Makes Fun of White Middle-Class New Yorkers.” The New York Times, September 1, 2016: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/02/arts/design/why-roz-chast-makes-fun-of-white-middle-class-new-yorkers.html

Oksman, Tahneer. “Overthinking Life and Death with Roz Chast.” Paper Brigade. Vol. 1. (2017): 107-110.

Witchel, Alex. “Drawn from Life.” The New York Times, May 30, 2014: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/01/books/review/roz-chasts-cant-we-talk-about-something-more-pleasant.html