Iggeret Ha-Kodesh

Written in the second half of the twelfth century, the Iggeret ha-Kodesh’s basic notion is that sexual relations between a married couple are sacred and that the state of both the husband and the wife during intimacy determines the character of their future child. The work, albeit brief, had great influence on Jewish communities throughout the ages. It underwent many printings, the earliest of which was in Basiliae (Basel) in 1546, with many later editions appearing in Amsterdam, Krakow, Altona, Berlin, and elsewhere. A fascinating study of how Kabbalah (whose burgeoning is understood as a response and a challenge to the Rambam’s views) infuses meaning into daily mitzvot, the Iggeret ha-Kodesh attempts to present a clear alternative to the Rambam’s negative attitude toward physicality and sexuality.

Controversy Over Authorship

The Iggeret ha-Kodesh (The Holy Epistle), a Kabbalistic work written in the second half of the twelfth century, has been mistakenly attributed to the Ramban (Moses ben Nahman or Nahmanides, 1194–1270). The question of the composition’s author has prompted various answers: Gershom Scholem (1897–1982) at first believed that the author was Rabbi Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla (1248–1325), a kabbalist who lived a generation after the Ramban. He later recanted this view and attributed the work to the kabbalist Rabbi Joseph of Shushan (thirteenth century), who was especially known for his erotic works. Around 1987, in an introduction to a facsimile edition to a work by Rabbi Yehoshua ibn Shuaib (first half of the fourteenth century), Shraga Abramson (b. 1915) claimed that the work was written by Ezra ben Solomon of Gerona (d. 1238 or 1245), one of the significant kabbalists of the thirteenth century. Rabbi Hayyim Dov (Charles Ber) Chavel (1906–1982), who published the Ramban’s works, also claimed after a long discussion: “… It is clear that the words of Rabbi Azriel are the foundation stone of the Iggeret ha-Kodesh …” (311). Charles Mopsik (1956–2003) shared Scholem’s early view that Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla was the author, though Moshe Idel (b. 1947) has more recently written that he tends to attribute the work to an anonymous author and its date to approximately 1280.

The deciding factor in attributing the Iggeret ha-Kodesh to the Ramban was that about seventy years after his death, Rabbi Yisrael Elnekaveh (d. 1391) included the entire work in his own book, Menorat ha-Meor, even prefacing and concluding it with an attribution to the Ramban. Similar inclusions of the entire work in other works may be found in Shevilei Emunah (Paths of Faith) by Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Aldabi (c. 1310–c. 1360). The work is quoted in full in Rabbi Elijah de Vidas’s (d. 1588) work Reshit Hokhmah (The Beginning of Wisdom), one of the most important works of kabbalistic ethics of Safed.

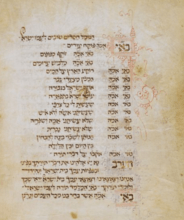

While the question of the Iggeret’s authorship is of utmost importance, it does not detract from the importance of this brief work itself, which had great influence on Jewish communities throughout the ages. It underwent many printings, the earliest of which was in Basiliae (Basel) in 1546. Many later editions appeared in Amsterdam, Krakow, Altona, Berlin, and elsewhere.

The Iggeret ha-Kodesh’s Kabbalist Premise

The basic notion of the Iggeret ha-Kodesh is that sexual relations between husband and wife are sacred and that the state of both husband and wife during intimacy determines the character of the future child. The child’s nature and essence are determined by its parents’ spiritual consciousness and the holiness of their intentions at the time of conception. The opening of the work uses theological sources such as the creation story to strengthen the argument that intimacy is holy. The work then provides more detailed explanations on how to achieve such sanctity, measuring it according to five standards: the nature of the conjugal act, the time that it takes place, the diet of the couple, and the act’s intentions and its quality.

Rejection of the Rambam

A close look at the opening of the Iggeret reveals that it attempts to present a clear alternative to the Rambam’s negative attitude toward physicality and sexuality. This kabbalist realizes that there is an enormous rift in Jewish culture between Maimonides’s Aristotelian tradition and kabbalistic tradition. Thus we can perhaps place the work within a broader trend, at the beginning of the The esoteric and mystical teachings of JudaismKabbalah, whose burgeoning is understood as a response and a challenge to the Rambam’s views.

The writer opposes the Rambam’s position, which claims, following Aristotle, that the sense of touch is disgraceful (The Guide for the Perplexed, part 2 Chapter 33), and attempts to counter it with a more positive outlook on sexuality. Throughout the work, this affirmative stance develops to such a point that one might say that by the end, not only are sexual relations viewed as holy, but through them one can empower the highest mystical experiences.

The writer presents several theses to counter the view of the human body as loathsome. He argues that if God in his wisdom created physical beings with defined limbs, then physicality must be considered part of the divine plan. “The matter is not as Rabbi Moses of blessed memory thought and believed in his Guide to the Perplexed, when he praised Aristotle’s statements. … Heaven forbid! Matters are not as the Greek work states, since this work contains subtle traces of heresy. If that heretic Greek had believed that the world is renewed by intent, he would not have said that. But we, who possess the holy Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, believe that the blessed God created everything as His wisdom decreed and created nothing shameful or ugly. For if we say that copulation is shameful, then the sexual organs are contemptible. But God, blessed be He, created them according to His word: ‘And you established them….” ( p. 323)

In addition, the writer asserts that the word “knowledge” (da’at), used in the creation story, denotes sexual intimacy, indicating that it is of noble origin: “The secret is that when a drop of sperm is drawn out in holiness and purity, it is drawn from the place of knowledge [da’at] and understanding, which is the brain.” Here the writer bases himself on medieval medical theories of the humors, such as those in Galen’s works, which claimed that sperm originates in the brain. The thesis that a connection exists between sperm and the brain, the center of thought, plays a central role as the work progresses, later explaining the ability to improve the fetus by mental observation alone.

Adam and Eve: A Case Study

The story of the creation of Adam and Eve also serves as evidence for the author’s thesis that the body is neither corrupt nor shameful. Here he distinguishes between their respective states before and after the Fall. The sin of Adam and Eve is viewed simply as transgression of God’s will and as a pursuit of physical pleasure. Only in such a state could it be possible to attribute any blame or blemish to their physicality, since the human body contains no defect. Therefore, in the story of Creation, the sexual organs are perceived similarly to the eyes or hands or the rest of the limbs.

The author’s interpretation of the story of the Garden of Eden reveals that on the one hand, he attempts to reject the Rambam’s view, but on the other, he retains his ambiguous attitude toward the body and its pleasures. A return to the state before the Fall means a return to the perception of sexual relations as clearly natural, but it also means a return to a state of sexuality without desire.

After analyzing the creation story, the author asserts that hidden in the sexual act is a deep secret: “This is the secret of man and woman according to the esoteric way of inner Kabbalah, and so copulation is a matter of great elevation when it is done appropriately. …” Here, the author hints at the great secret inherent in sexuality, which is connected with the secret of the cherubim. If sexual relations were indecent, “the Lord of the Universe would not have commanded them or placed them in the most sacred of places, which is on a very profound foundation.” At this stage, it appears that the author wishes to base his claims not only within a The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhic framework, but also within mystical kabbalistic ones. Sexual intimacy takes place between two people not only in order to perpetuate human existence or in simple fulfillment of God’s command; it must also be perceived as a mystical act of the first order.

An Alternative to Rabbinic Notions of Sexuality and Intimacy

The fascinating example of the cherubim heightens the innovativeness of the author’s proposed alternative to the familiar rabbinical notions, which compare union in the lower worlds to union in the higher ones, as already hinted at in the Lit. "teaching," "study," or "learning." A compilation of the commentary and discussions of the amora'im on the Mishnah. When not specified, "Talmud" refers to the Babylonian Talmud.Talmud, BT Yoma 54:71: according to Rav Katina, “When Israel ascended on pilgrimage, they would draw back the curtain of the Ark and show them the cherubim in intimate embrace, and tell them: See how great is God’s affection for you, like the love of man and woman.” But the Talmudic saying does not develop the concept of intent, which is central to the author of the Iggeret ha-Kodesh, nor does it detail the relationship between the higher and lower worlds as the author does.

It becomes obvious to the reader that the author is describing an entire structure which the act of intimacy builds, claiming that the goal of sacred union or the parents’ goal of producing healthy male offspring merges with the higher structures and lofty spheres. Instead of presenting the sexual system as horizontal in character, he presents it as vertical, with the Shekhinah and the higher worlds connected to reality through the union of husband and wife. Thus not only is the Shekhinah a partner in the union, but the goal of the sexual act itself becomes to draw spiritual abundance and blessing down from the higher world.

Sex as Mystical Kabbalistic Meditation Practice

From this perspective, we can see in this early work the presentation of a highly developed mystical-theurgical system. The work’s strength lies in its ability to clarify theosophic mystical and deep theurgical concepts, which are concentrated into one sole act: copulation. The work is a fascinating case study of how Kabbalah infuses meaning into daily A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvah.

Henceforth, the sexual act is perceived as an active, concentrated deed whereby a human connects the upper and lower worlds. The author identifies four significant stages in the act: 1) purifying one’s thoughts; 2) elevating one’s thoughts; 3) devoted concentration and 4) drawing down of influx [meshikhat shefa].

The author explains that the mind’s ability, through the art of meditation, to draw spiritual abundance from the upper worlds derives from the mind’s upper source, and from this high, Godly source, a person can attain elevated things by mental capability alone. If mental elevation accompanies the act of sexual union, it can also affect the nature of the fetus in this world. This principle seems as evident to the writer as that of water returning to its source.

… Know that as the spring of water is drawn from a high to a low place, so there exists strength to elevate the water to another high place corresponding to the height from which it flows. Thus the masters of Kabbalah know that human thought comes from the rational soul which is drawn from the higher worlds. The mind contains strength to expand and elevate itself, attaining the location of its source. Upon arriving at the source, it cleaves to the supernal light that is drawn from there, and the woman and man become one. When the mind returns from the upper world to the lower one, everything resembles one line, and the same supernal light is drawn downward by the strength of the mind. … Then the clear light is drawn down and spreads itself upon the place where the thinker sits. …

These statements allow us to determine the turning point that can occur as a result of mystical meditation; the act of union below creates, through mystical meditation, “one line” from above to below. The dynamics of the lower world are replaced by a linear dynamic that connects upper with lower. This wonderful relay point between sexual activity and the supernal world occurs during the special processes of the meditating mind.

Factors of Sexual Intercourse And Their Impacts On The Union

Besides the doctrine of mystical meditation in four stages which the author develops in this early work, he also discusses additional conditions that can affect the union. Here we see that the author describes the time of the successful union, the appropriate place for it and foods that affect sperm quality. The author sees these rather prosaic conditions as having great influence on the child born of the union, lending strength to some Talmudic opinions that the most appropriate time for sexual relations, for Torah scholars, is after midnight on Sabbath eve. He also warns them against having relations too soon after the meal. These Talmudic opinions are enveloped in Kabbalistic theory. The Sabbath, for example, is the preferred time for mystical activity of this type since it represents the Shekhinah, thereby enabling spiritual connection. The writer terms the rest of the days of the week “days of physicality.”

The author also suggests avoiding forbidden food, which imprints evil characteristics on the soul that may affect the child’s nature. He also explains the laws of ritual slaughter in terms of embodying spiritual characteristics and mental abilities that exist more in animal than in vegetable foods. To this, the writer adds the suggestion of eating to the point of satiety but not overeating, because of the scientific theory connecting blood quality with the quality and purity of the sperm, which he propounds throughout the work. In the second part of the work, the author develops the theory that one’s thoughts during the sexual act can influence the nature of the child conceived. The reader is made aware of the writer’s unshakeable belief in the influence of consciousness and imagination on reality.

Sex in the World of Mitzvot

When a man unites with his wife, if his imagination and thoughts concentrate on matters of wisdom and understanding, good and worthy qualities, those thoughts have the power to create an image in the drop of sperm. … This is the secret of [the verse]: Jacob then got fresh shoots of poplar, and of almond and plane, and peeled white stripes in them, laying bare the white of the shoots, etc.

In an extraordinary interpretation, the writer explains the sages’ statement “God considers good intention as if it were deed” (BT Kiddushin 40a) to mean that intention can actually create deeds. This is a subversion of the common interpretation of the sages’ statement. Thus Iggeret ha-Kodesh is one of the earliest works to express the notion that would later be developed in many Kabbalistic works, that meditation is not simply contemplative, but can also design and activate the reality. The holiness of sexual union is therefore the full merging of the spiritual and physical realms.

The exciting mental tasks required of both man and woman during the sexual act elevates the act to one that cannot be disparaged. The A biblical or rabbinic commandment; also, a good deed.mitzvah is not a simple ritual; it is umbilically tied to a multitude of systems that connect human beings to the supernal worlds. Iggeret ha-Kodesh succeeds in imparting profound significance to the mitzvah, which the rabbinical view had not hitherto succeeded in doing. In it, sexual union becomes a true ma’aseh merkavah—the mystic study of the Divine Chariot. We can attribute the author’s motives to the central trend of medieval Jewish thought. The author’s interest in ascribing meaning to ritual is reflective of the major trends of medieval Jewish thought which sought to explain and to enrich the world of Jewish mitzvot.

Abramson, Shraga. “Iggeret ha-Kodesh Attributed to the Ramban” (Hebrew). Sinai 90 (5/6) (1982): 232–234.

“Iggeret ha-Kodesh.” In The Writings of the Ramban (Hebrew), edited by R. Hayyim Dov Chavel. Jerusalem: 1963.

Biale, David. Eros and the Jews. California: 1992.

Cohen, Jeremy. “Intention in Sexual Relations According to Twelfth- and Thirteenth-Century Rabbinical Opinion” (Hebrew). Teudah 13 (1997): 155–173.

Garb, Yonatan. “The Concept of the Power of Intention in the Kabbalah” (Hebrew). Ph. D. diss., Hebrew University of Jerusalem: 2000.

Guberman, K. “The Language of Love in Spanish Kabbalah: An Examination of the Iggeret ha-Kodesh.” In Approaches to Judaism in Medieval Times, vol. 1, edited by David R. Blumenthal. Brown Judaic Studies, vol. 54, Chico, CA: 1984, 53–105.

Harris, M. “Marriage as Metaphysics: A Study of the Iggereth ha-Kodesh.” HUCA 33 (1962): 197–220.

Idel, Moshe. “Sexual Metaphoros and Praxis in the Kabbalah.” In The Jewish Family: Metaphor and Memory, edited by David Kraemer. New York and Oxford: 1989.

Scholem, Gershom. “Did the Ramban Write Iggeret ha-Kodesh?” (Hebrew). In Mehkerei ha-Kabbalah, Tel Aviv: 1998.