Nan Goldin

Nan Goldin in 2009. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Nan Goldin fled a conventional Jewish middle-class home at the age of fourteen. Starting in the 1970s, she used her camera to document her own life and that of her friends, her alternative family. Her pictures revealed intimacy and violence, love and abuse, sexuality and addiction, in the downtown punk scene of New York in the 1980s, a world subsequently devasted by AIDS. She adopted a slide show format to be a mirror to her friends, and ended up mirroring their lives to the outside world. Goldin’s innovations in personal documentary expanded the range of documentary subject matter to embrace emotion. She also subjected herself to searing self-portraits, creating a visual diary of her life.

“The people who carried my history, the people I grew up with and I was planning to grow old with are gone,” Nan Goldin wrote in the afterword to The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. “Our history got cut off at an early age. There is a sense of loss of self also, because of the loss of community. But there’s also a feeling that the tribe still goes on.” The photographer Nan Goldin is not a Holocaust survivor or the daughter of Holocaust survivors. Her language, redolent of loss and hope, the dream of continuity amidst death, of self embedded in community, sounds all too familiarly Jewish, too close to classic Jewish texts both of despair and renewal and of intimate consolations. But Goldin is not reflecting on her family or the Jewish people; she is referring instead to friends who have died from AIDS.

Family

To invent an alternative family, Goldin first had to flee expectations that suburban middle-class parochialism could inflict on Jewish daughters. The youngest of four children, she was born in Washington, D.C., on September 12, 1953, to Hyman Howard (1913-2012) and Lillian Kantrovitz Goldin (1915-2017). Her parents had met in the Boston Public Library. Her father received a doctorate in agricultural history from Harvard University but realized that discrimination against Jews prevented him from securing an academic position. After marriage, her parents moved to Washington, D.C., to find work with the Federal government. Nan’s older siblings included a sister, Barbara, the oldest, and two brothers, Jonathan and Stephen.

Goldin’s father accepted a professorship at Boston University and the family moved to Boston after the suicide of her older sister, Barbara Holly Goldin, on April 12, 1965. A talented musician, Barbara threw herself across the railroad tracks outside Washington’s Union Station and was killed by an oncoming train. When the family was sitting Lit. "seven." The seven-day mourning period held following the death of an immediate family member: spouse, parent, child or sibling.shivah (the seven-day period of mourning) at home, eleven-year-old Nan was sexually abused by an older male relative who claimed he had been in love with her sister.

Becoming a Photographer

At fourteen Goldin ran away from home. With her parents’ support, she attended a hippie free school and shared a group apartment in Boston. At eighteen she started to photograph. She befriended drag queens, documenting their glamour and vulnerability. For three years she studied photography at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In 1978, she moved to New York, where she worked as a bartender. With her camera, she entered the downtown gay, punk, and drug scene. She photographed drag queens, transvestites, and addicts. Her photographs captured the raw intimacy of relationships, as well as the emotional pain.

At some point Goldin decided: “I don’t ever want to be susceptible to anyone else’s version of my history” (Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 9). Photography gave her tools both to make history and to invent family. The photograph documents and triggers “real memory.” The photograph produces as well as reproduces her relationships.

Photography as a Redemptive Project

I’ll Be Your Mirror, the title of both Nan Goldin’s 1996 retrospective show and a separate film, extends an invitation to document her extended “family of friends” and by doing so to save them and thereby herself. Goldin has invested herself in photography as a “redemptive” project: “I still believe that pictures can preserve life rather than kill life” (Ballad of Sexual Dependency, 146). This redemptive project echoed Jewish, especially mystical, understandings of human purpose in the world. Goldin, however, did not explicitly draw upon any Jewish texts.

If Goldin was her subjects’ mirror in their early relationship, once drawn into the institutional world of art exhibitions and books, she also became a window for an audience of outsiders. The ambiguity of photographic revision calls attention to the issue of agency in the photographic process.

As Goldin’s exhibition practices evolved, she developed a complex, layered relationship to the rounds of editing that create photographic value by promoting individual pictures into existence, even though she was most interested in connections among multiple portraits across time. Initially she shared photos of her friends from bags of drugstore prints. To save money after shifting to color work, Goldin used slide film. She projected many hundreds of slides within her “family of friends” essentially unedited.

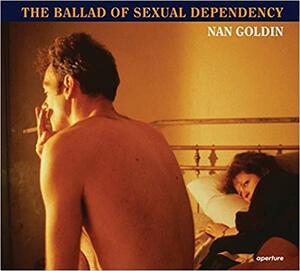

Then Goldin became interested in the interaction of the slides with music and began to adjust their arrangement. In its “performative mode,” The Ballad of Sexual Dependency was a frequently reedited assortment of around 700 slides. Each image appeared for approximately four seconds. Each gained meaning in relationship to the one that preceded and followed it. They possessed immediacy and ephemerality. To look at the photographs involved becoming a spectator, sitting in a darkened room for approximately 45 minutes.

In 1985, she published a book version of The Ballad with 125 of these images. “The text of The Ballad,” Goldin explained in an interview, “talks about bonds stronger than blood—family bonds, because the family was bonded by sensibilities, political views, aesthetics, sense of humor, shared history” (Holert, 274). The themes she addressed covered love, power, sex, addiction, abuse, and death. But she did not abandon her slide-show format.

Goldin’s redemptive project of mirroring continues through an ongoing process of winnowing and arranging. Many of her gallery exhibits still devote spaces both to luscious large Cibachrome prints and to slide shows with music. She likes the slide-show presentation format because it keeps her editorial options open. Goldin struggled to reconcile the ideal announced in her title, to be a mirror for her alternative family, with her actual working processes of selection and elimination.

Self-Portraits

Goldin has consistently photographed herself along with her friends. These self-portraits reveal her own self-perception in performative mode. She took one of her most powerful self-portraits, “Nan After Being Battered,” in 1984, a month after her boyfriend, Brian, assaulted her. After viciously attacking her eyes, her means of engaging the world, he then scrawled the words “Jewish American Princess” in lipstick across her mirror. No matter what Goldin did, she could not escape this stereotypical representation of Jewish women that flourished in the 1980s. The beating nearly left her blind. She took the photographic self-portrait so she would never forget what he did to her. It was a kind of visual diary.

Consider the image chosen for the cover of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. “Nan and Brian in bed, New York City 1983” portrays a couple, with a portrait of Brian in the background pinned to the wall above Nan’s head. The image is split by light and shadow, dividing woman from man. At the prospect of being appraised twice, or perhaps thousands of times, Brian seems determined to block all viewers out. It is left to the viewer, studying the fear, desire, confusion, or anger on this image of Nan’s face, to decide whether she should be glancing or glaring. “Nan and Brian” is one of several stage-managed pictures that bracket the body of Goldin’s work, girding it against casual, uncaring eyes. Though she made her own expression and triggered the shot in her own time, Goldin was surprised by what it revealed. For her, too, engaging this charged image was to be maneuvered out of habitual spectatorship.

Goldin rejects the notion of the directorial mode of her photography. “In no way was I directing the pictures; they’re just fragments of life as it was being lived. There was no staging,” she insisted in an interview. “When you set up pictures you’re not at any risk. Reality involves chance and risk and diving for pearls” (Holert, 233).

Goldin has lived in Berlin and Paris as well as New York City. Before her parents’ deaths, she reconciled with them.

“With her camera, Goldin had generously held a mirror up to the chosen world of her friendships, but there’s the other truth,” as Frances Brent notes, “that the Jewish middle-class world of her origins and the re-created world of her art are mirrors to one another.” Goldin made human intimacy her subject, in all its complicated permutations.

Selected Works

Nan Goldin, The Other Side. Gottingen: Steidl, 2019.

Portfolio. Hamburg: Mosaik Verlag GmbH, 1999.

Nan Goldin: I’ll Be Your Mirror. Elisabeth Sussman and David Armstrong. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1996.

A Double Life. New York: Scalo Publishers, 1994.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. New York: Aperture, 1985.

Brent, Frances. “Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency, from CBGB to MoMA, Or, how a nice Jewish girl got her nose broken by her bad boyfriend.” Tablet, August 10, 2016, https://www.tabletmag.com/sections/arts-letters/articles/nan-goldin-bal….

Holert, Tom. “Nan Goldin talks to Tom Holert—’80s Then—Interview.” ArtForum 41, no. 7 (March 2003).

MacDonald Moore and Deborah Dash Moore, “Observant Jews and the Photographic Arena of Looks,” “You Should See Yourself!” Jewish Identity in (Post)Modern American Culture, ed. Vincent Brook. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006: 176-203.

Thomas, Dana. “Shooting Away the Pain.” Newsweek, November 25, 2001.

Townsend, Chris. “Nan Goldin: Bohemian Ballads.” In Phototextualities: Intersections of Photography and Narrative, ed. Alex Hughes and Andrea Noble. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2003.