Writing Through Grief

One afternoon after several appointments with oncologists and radiologists, our family gathered around the kitchen table, trying to figure out what to do. My sister raked her fingers through her shiny chestnut hair; she couldn’t stop touching it now that she knew it would soon be gone. “I just want to see my kids graduate,” she said, and then blinked hard to stop the tears.

That’s when my father began to unbutton his shirt. On his strong, speckled chest, something gleamed. He ducked his head and pulled off the necklace, dangling it before all of us. From the chain hung a golden chai. He had worn that symbol ever since I could remember. “Life,” he said. And then he pushed out of his chair and shuffled around the table to lean over Margie. He kissed her forehead and fastened the chai around her neck. My father was giving his own life to Margie. She squeezed the chai as if she were calling upon God to pay attention to her.

At first, the chai seemed to work miracles. After the first few treatments, the doctor calmed us by explaining his plan. Margie would get all that he had to offer: chemotherapy, radiation, CT-scans, and MRIs. “At this point,” he told Margie, “you can run a marathon if you want.” I watched as he scanned his computer, examining the test results. He assured us that the cancer in her lungs had decreased. The metastasis to her hips was shrinking from the radiation. Aside from the cancer, she was healthy.

My duty was to keep that positive feeling alive after we left the doctor’s office. I tried to convince myself that her body would outsmart the cancer, even though she was Stage IV. As they said in the cancer circles, which we had reluctantly joined, there is no stage V. But, miracles could happen, right? I needed to rely on my faith and hope.

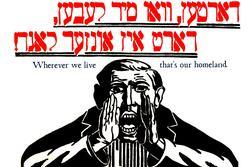

One day, I told Margie that my friend was traveling to Israel. So here was another chance: We could ask my friend to put prayers in the Western Wall. During the week that followed, I collected notes from our family and friends, and folded them up into tiny pieces. Days later, I imagined my friend in Jerusalem sticking the papers in the crevices of the wall, shoving them deep so that they passed to some secret other side, as if the wall were God’s mailbox. That wall acts as a beacon for Jews all over the world, and we had joined this family of people with desperate hopes.

A year went by, and after Margie finished six rounds of chemotherapy, she regained her strength and energy. At our next oncology appointment, our doctor told us about a new cancer drug, Tarceva, that just targets cancer cells. Unlike traditional chemotherapy, it had few side effects. My sister took the pill every day. Her hair grew back. The nausea ended. She had energy. Now we could pretend that her life would be normal again. All she had to do was take that pill and see her doctor every three weeks.

It was difficult to accept that my 43-year-old sister, who never smoked, always exercised, and ate healthy food, got diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. How could this happen to a young, beautiful, vibrant wife, mother, daughter, and sister? Through many conversations with my Rabbi, I learned that God's role isn't to make sick people better, but perhaps to help sick people be brave. We can be spiritually whole even when our physical health is failing.

I attended Shabbat services and participated in the traditional prayer for healing the sick, the Mishabarach. “Excuse me,” I said as I shimmied past the people in my row of seats, feeling their eyes on me while I made my way to the bimah. I told the Rabbi my sister’s Hebrew name, Miriam Etka, with a strapping voice, as if pronouncing her name loud and strong would give her a better chance. Later, he told me that if the sick believe that people are praying to God on their behalf, they can’t help but feel cared for and nourished. The community itself—how they come together to focus a beam of love on the sufferer—can help one’s spirit and soul to be in shape even when their body is not.

During the next few months, Margie kept a vial of Tarceva by her bedside and wore the chai around her neck. The pill was working—but for how long? When we went back to the doctor for test results, we simmered with anxiety. “Looks good, looks good,” the doctor assured us. “There is very little cancer in your lungs. Tarceva is doing its job.” Margie and I looked at each other and smiled.

“This is fabulous news,” I said cautiously, catching the doctor’s eyes.

“How long do you think Tarceva will keep working?” Margie asked. “Will it cure the cancer in my lungs?”

The doctor paused as he considered Margie’s question. Answering carefully, he said, “It would be highly unusual for a complete remission. But you’re stable, which is excellent news. Let’s take it month by month.”

After a long, uncomfortable silence, my sister relented with a quiet “okay.”

For a while, Tarceva felt like a miracle on the order of Moses parting the Red Sea and God delivering manna from heaven. Margie and I resumed our routine of exercise and yoga classes. We had family dinners and celebrated birthdays with our husbands, parents and children. We had fun in New York, shopping for new spring fashions and checking out restaurants downtown. I could never have imagined how satisfied I would be to see Margie engrossed in Jersey Boys on Broadway.

Eight months later, the targeted drug stopped working and the cancer spread to her brain. My sister lost her hearing, her balance, and her ability to chew. But at the same time, Margie rarely cried anymore. She no longer asked me whether she’d beat the odds. The Jewish rituals continued to be a blessing for us—though not in the way we’d hoped. Even though Margie’s body was failing her, her Rabbi said she could have won a marathon with her spirit and soul. Margie was able to defy her illness; she refused to let it get the best of her. Our prayers smoothed away Margie’s fear. They couldn’t save her life, but they gave her the poise to face what was coming with dignity.

After she died, reeling from grief, I immersed myself in writing. I am lucky enough to live in Boston where there’s an organization called GrubStreet, one of the premier writing institutes in the county. GrubStreet saved me. For ten years, I took every class from “Jumpstart Your Writing” to “Memoir, Personal Essay” to “Novel in Progress.” During these classes I was able to be with my sister even though she’s no longer here. By writing about a devastating loss, I became brave enough to make my grief a part of me, and realized that I had a story to tell.

Helene’s novel Appearances comes out this month.

Thank you so much..

Very moving and beautifully written.

I am so sorry for your loss, but so glad you found a healing way through it. May your life be filled with good memories and joy.