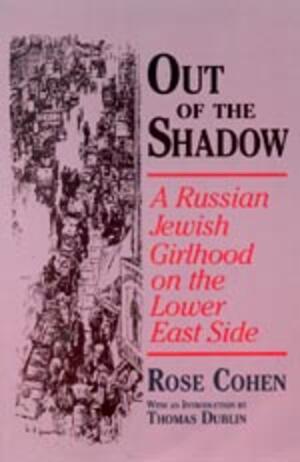

Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side

About this book

by Rose Cohen with Introduction by Thomas Dublin

Pages: 313

Format: Paperback

ISBN: 0801482682

Publisher: Cornell University Press

Download this guide: PDF

Out of the Shadow: A Russian Jewish Girlhood on the Lower East Side was written by Rose Cohen, another relatively anonymous Jewish woman who also believed that her personal story was worth preserving. Cohen's first-hand account of tenement life and sweatshop labor on the Lower East Side, replete with generational and interreligious conflicts, sheds light on the immigrant generation's heartaches and longings.

Discussion Questions

- How is Rose Gollup (then Cohen) made aware of her Jewishness in the Pale of Settlement? On the Lower East Side? Why does she observe of life on the Lower East Side that "on the whole we were still in our village in Russia?" How does her Jewishness evolve over the course of time?

- Starting life in the new country disrupted many older habits of behavior, beliefs, and relationships. Rose's account suggests several areas of change for Russian Jews in the course of the immigration process. What changes in relations among generations are depicted in the book? How does immigration exacerbate the normal disturbances between parents and children? How do Rose's experiences differ from those of today's immigrants?

- What religious changes are evident for the Gollup family between life in Russia and on the Lower East Side? How do Rose Cohen's ideas about Gentiles change in the course of her life in the United States?

- How do gender roles and interrelations between men and women change with resettlement and accommodation for Jews on the Lower East Side?

- How did Rose Cohen's sense of the relationship between her mother and grandmother affect her thinking when considering marriage to Israel, the Broome Street grocer to whom she was briefly engaged? What sort of change is revealed by the comparisons that Rose made in her mind?

- The intervention of Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry St. Settlement (sometimes called the Visiting Nurses Settlement) changes Rose's life in many ways. Rose wrote: "Miss Wald comes to our house, and a new world opens for us." Wald sends Rose to a hospital "uptown," which Rose views as strange as a "different country," and Rose increasingly becomes involved in settlement life. What does Rose learn through knowing Lillian Wald? What world does she glimpse that she hadn't known? How does this encounter change her life and values?

- Compare anti-Semitism in Russia with anti-Semitism on the Lower East Side as described by Cohen. What are the similarities and differences in terms of Jews' relations with the broader societies in which they found themselves? How have you seen anti-Semitism expressed over the course of your own lifetime? Have any changes taken place?

- Even as a child Rose Cohen had a very strong sense of right and wrong and the courage to stand by her convictions. What incidents in the autobiography reveal this dimension of her personality? How do these traits express themselves after she emigrates?

- Based on Cohen's account, describe sweatshop garment work on the Lower East Side. What grievances did workers have? Did women experience different hardships than men? What did they do to improve their circumstances? How did Rose Cohen relate to these efforts? Jewish women like Rose often became trade union activists in greater numbers than other ethnic or American-born workers. Why do you believe this was so? Have there been women in your family who were involved in labor or political activism?

- The book ends inconclusively with the story of Rose's brother's success in school. Why might Rose have concluded with this story rather than with a focus on her own history? Create an ending that you think might suggest what happened to Rose. How does this story compare to the fate of women in your own family who emigrated from other countries?

Critical Essay

by Tom Dublin, Professor of History at Binghamton University, State University of New York

Rose Gollup Cohen came to the United States in 1892 at the age of 12, traveling with an aunt to rejoin her father who had emigrated from the Pale of Settlement in the Russian empire a year and a half earlier. Later she wrote one of the best first-person accounts we have of sweatshop work and tenement life on New York's Lower East Side. Moreover, her autobiography offers rich evidence of the conflicts Jewish immigrant young women experienced as they moved from an old-world to a new-world identity over the course of their lives.

Cohen began writing her autobiography in an English language class at the Thomas Davidson School at the Educational Alliance. It was first published in 1918, when she was 38 years of age. Written over a number of years, relatively close to the time of her initial migration, Out of the Shadow has an immediacy that is unusual for the autobiographical genre. Cohen wrote vividly about her childhood in the Pale of Settlement, her father's escape from Tsarist authorities, her passage to America, and her steady assimilation into American culture. Moreover, the account is not colored overly by Cohen's adult experiences. Actually, Cohen never figured out how to connect herself as writer to the "Rahel-Ruth" of her narrative, and the story winds down rather inconclusively, with the reader losing track of her, perhaps 22 years of age, at the story's end.

Jewish Women Workers on the Lower East Side

Gender played a major role in shaping Rose Cohen's life as she depicted it in Out of the Shadow. When her father sent two pre-paid steamer tickets, he specifically suggested that she and his unmarried sister, Masha, be sent to New York. He knew from a year and a half on the Lower East Side that they would find steady employment in the tenement stitching shops of the immigrant quarter. Her father also worked in the garment trade, but generally speaking demand was greater for women workers who were hired at lower wage rates than men, and women predominated in the less skilled jobs in the industry. When a union (probably the United Hebrew Trades) began organizing among the garment workers, Rose's father joined and took her to a meeting hall on Clinton Street where women workers listened to a young male organizer exhorting them to join the union. Rose joined together with the other young women in her shop, but the union did not survive very long.

The Experience of Immigration

Cohen provides rich anecdotes about the experiences of recent Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side. Her mother and siblings arrived about a year after she and her aunt had emigrated, their passages paid for by savings her father had accumulated in the intervening months, no doubt drawing in part on his sister's and daughter's earnings. She offers recollections of revealing incidents that speak to issues of assimilation and Americanization for the immigrant newcomers. When she first arrived at Castle Garden, she could hardly recognize her father, as he had trimmed his beard and forelocks since he had come to America. Later, she was aghast to realize that he carried money and bought her fruit on the Sabbath. Finally, a year later, she urged her mother to go without the traditional kerchief worn by married Orthodox Jewish women. Rose Cohen had gone from being a resisting traditionalist to an enthusiastic Americanizer in the course of her first year in the United States.

Class Differences in America

She was also a keen observer of class differences in America. She described in detail a home visit during a bleak depression period by a social worker for a relief agency, noting the questions he posed and her responses. He asked her repeatedly about the family's needs and instinctively she denied that they needed anything--not clothing, shoes, or food. Even though she and her father were out of work, her mother was ill, and the landlord came daily seeking anything the family might pay toward the rent, she had a pride that refused charity. Luckily, the agent saw through her denials, realized the family's need, and sent four dollars and a load of coal.

Class also was particularly visible when the family finally acknowledged its dire straits and permitted an agent to place unemployed Rose as a domestic servant in a family. It was hard to eat at the table with her employer's family, though, so great was the contrast between the "soup, meat, [and] potatoes" served at their meals with the bread and sugar-sweetened water that her family ate. Rose had been on the weak side and had been protected from hard domestic work by her family, but she had to wash and iron clothes, scrub floors, scale fish and clean fowl, and run errands to the nearby store for her employer. And while those who employed her had beds to retire to, she was expected to throw two quilts over chairs when she turned in at the end of a hard day's work. After two months, concerned about the changes she sensed in herself, she quit domestic service, saying to herself, "I would rather work in a shop." There, though she might be put upon by a demanding boss, at least she could leave the shop at the end of the day and she didn't have to put up with the obvious inequalities that made domestic service such a trial for her.

Rose's Engagement

As her story proceeds, we see Rose emerge as an assimilated individual, increasingly different from the ideal of the older, traditional Russian Jewish woman. Her new identity is particularly evident in her short-lived engagement to Israel, a young Jewish grocer from Broome Street. The courtship was shaped by a fascinating mix of old- and new-world traditions. Fulfilling an errand requested by her mother, Rose first meets the young man while making a purchase at the store where he worked. She knew nothing about her parents' intentions until they announced that Israel and his uncle would be paying a visit.

In accepting the engagement that her parents so desired, Rose played the dutiful old-world daughter and gave them pleasure. As the engagement played itself out, though, Rose could not give herself to someone she did not love; she could not accept the common old-world view that her love would grow after the marriage. She found that books meant almost nothing to her husband-to-be and that he did not share her love for reading. Moreover, she would have to become a member of her mother-in-law's household. All was arranged for her and she would have virtually no say in how she lived. Finally, she would have to become Israel's assistant in his store. Unable to imagine herself happy in the marriage, household, or store, she broke off the engagement. In the end, Rose was moved by the new-world conception that one should marry someone one loved rather than follow one's parents' wishes. In the failed engagement we see the triumph of new-world gender expectations over those of the old country.

Lillian Wald and the Henry Street Settlement

Intervention by Lillian Wald of the Nurses' Settlement (also known as the Henry Street Settlement) rather than marriage eventually permitted Rose Cohen to escape from her Old World family and begin the first tentative steps to becoming her own person on American terms. A recommendation letter from Lillian Wald got Rose admitted as a patient to the uptown Presbyterian Hospital where she began to recover her health and meet New Yorkers outside of the Russian Jewish world of the Lower East Side. She commented in her autobiography that she first "caught a glimpse" of Americans while in the hospital, for living in the Lower East Side had seemed little different from "our village in Russia." And when she returned home after her hospital stay, she remarked, "it seemed to me that now I did not belong here. I did not feel a part of it all as I did formerly." She determined to learn English and to begin to feel more a part of the American world to which she had been exposed at Presbyterian Hospital.

The Lower East Side as Jewish Neighborhood

Rose Cohen's comments about the Lower East Side provide an appropriate entry into the significance of place in shaping the character of her immigrant experience. After all, she had not come just to America, but with her father had settled in one very specific corner of the nation's largest city, the Lower East Side. Several other contemporary accounts remind us what was unique about this neighborhood. A guidebook from the period, The Sidewalks of New York, described the Lower East Side thus: "the enormous area east of the Bowery and south of 10th Street, which ... is almost exclusively Jewish." There one found "Yiddish signs, Yiddish newspapers Yiddish beards and wigs." The Lower East Side was also probably the densest urban neighborhood in the world in the early twentieth century. The newspaper editor, novelist, and socialist, Abraham Cahan, understood this aspect well: "The East Side, as it is popularly known, covers a comparatively small area, something less than half a square mile, wherein is crowded a little city of its own, the ghetto, with a population of 500,000 souls. Half a million men, women, and children, almost exclusively Polish and Russian Hebrews." In this "city of its own," Rose Cohen had met hardly any "Americans," that is, any English-speaking native-born Americans. Only her illness and her chance meeting with Lillian Wald of the Henry Street Settlement took her out of this world and introduced her to Protestants from Uptown. And once Cohen discovered there was a world beyond the old-world Russian village of the Lower East Side, her own internal turmoil increased dramatically.

A Lower East Side Girl Meets the "Uptown" World

In the final pages of the autobiography the worlds of Uptown and the Lower East Side vie for Cohen's allegiance. She recovered enough to return to work, but periodically felt compelled to call on Lillian Wald to pour out her grief, and Wald arranged for a variety of alternatives to her normal work and home life in the immigrant ghetto. Cohen spent several summers at a Connecticut retreat for immigrant children, working on the staff of the home. She found employment on one occasion in a cooperative garment shop with a Miss O'There (a thinly veiled Leonora O'Reilly, to whom the autobiography is dedicated). She met upper-class friends of her benefactor and felt increasingly alienated from the world of the Russian immigrant Jewish world she had known.

An Inconclusive Ending

At the story's end, Cohen was no longer the wide-eyed immigrant girl who had debarked at Castle Garden ten years earlier, but neither was she well integrated into the American world she found so appealing. She took pride in her family's accomplishments, as her father moved from tailoring to running a small grocery store, with crucial help from a sister, while one brother gained admission to Columbia University. She, herself, though was uprooted and uncertain. As she related her experiences in the autobiography, she had no interest in marriage nor had she clear prospects that would have permitted her to support herself in the future. Although she had married and given birth to a daughter, Evelyn, before the publication of Out of the Shadow, there is no hint of husband or daughter in her account. She drew her narrative to an inconclusive closing with very cursory descriptions of her father, sister, and brother. She herself had faded out of focus.

Out of the Shadow appeared in 1918 and Rose Cohen continued to publish short stories in succeeding years. Her last publications appeared in 1922, and she spent the summers of 1923 and 1924 at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, N.H. At that point the document trail runs out except for a Rolodex entry from the records of the MacDowell Colony noting a 1925 date for Cohen's death. Whether she died or committed suicide we will probably never know for sure. We know that she had separated from her husband in these last years; we know that publication of her writing had slowed down or stopped. We can see in her autobiography an uncertainty and lack of confidence that speak to some confusion about her own identity and sense of purpose in life. She seemed most at home exploring the world of her Russian childhood and her changing identity on the Lower East Side. In the end, she seemed never to have made a sure transition into a new American identity. We have a poignant account of her old-world origins and new-world struggle that speaks to readers in the early twenty-first century as it did to her contemporaries eighty years ago. Her life, like that of contemporaries of her immigrant generation, defies easy generalization. Still the window she opened up on herself and her times offers compelling views for readers today of a world that has shaped our own and into processes that continue to operate with new generations of immigrants in our own times.