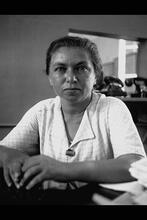

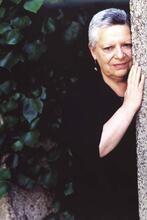

Janette Fishenfeld

Janette Fishenfeld, the daughter of a Bessarabian immigrant and a Brazilian Jew, grew up in Niterói, Brazil, where she spent most of her life. She was an author of short stories, a columnist, a Zionist activist, and a leader in the Women’s International Zionist Organization. Many of her stories portrayed a nuanced, sometimes messy Brazilian Jewish community, while others displayed an idealistic view of life in Israel.

Family and Early Life

Jews of many national origins started to settle in Rio de Janeiro by the end of the nineteenth century, continuing in organized waves of entry into the country during the first half of the twentieth century. Around 1926, Aron Diamant arrived in the city among a contingent of Bessarabian immigrants. There he met and married a young Brazilian Jewish woman, Luíza Salomão, with whom he moved to the city of Niterói in the state of Rio de Janeiro. On September 28, 1932, Janette, their first daughter, was born. She was followed by a son, José, and a second daughter, Bella. Janette was raised and educated in Niterói. While at high school, she collaborated in the organization of a student newspaper. At the age of fourteen she was awarded the first prize in a literary contest sponsored by her school.

One of the few women of her time to attend university, Janette graduated in biology. During her college years, she collaborated in the short-lived magazine Arte Jovem (Young Art) and contributed articles and poems to other local gazettes.

Janette married Luís Laizer Mayer Fishenfeld (b. March 1, 1930), an accountant and businessman. The couple continued to live in Niterói, where their two daughters were born: Suzette (b. November 23, 1953) and Rejane (b. October 12, 1956). After a brief period of teaching in the high-school system, Janette Fishenfeld decided to stay at home and raise her daughters. In February 1972 the family moved to Rio de Janeiro.

Jewish Activism and Writing

Janette Fishenfeld stayed in constant contact with the Jewish community, volunteering her free time to help in the organization of events, conducted primarily by WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization). She became a permanent member and coordinator of its cultural department in 1961.

In that same year, Janette began to collaborate in a leading Jewish magazine in Brazil, Aonde Vamos? (Where are we going?). As a result of her popularity with the magazine’s readership, she was invited to write a regular column for the monthly publication. This consisted mainly of reportages, followed by short stories and a few poems. The reportages were based on contemporary events involving the Jewish community of Rio de Janeiro, family life, and news of Jews in the world at large. She also collaborated in the magazine Menorah, mostly with short stories. Her only book, Os dispersos (The Scattered Ones), was published in 1966, while she was still living in Niterói. It comprised four short stories that had already appeared in Aonde Vamos? and three others, published for the first time.

The author’s philosophy of life as a Jew is clearly presented in her writings: the preservation of Judaism through the continuation of some aspects of religious and traditional rituals in the Lit. (Greek) "dispersion." The Jewish community, and its areas of residence, outside Erez Israel.Diaspora, and the responsibilities vis-à-vis Israel. It was perhaps no coincidence that her monthly column was named “Imagens no meu espelho” (Images in My Mirror). Indeed, both her fictional works and the reportages reflect the author’s concern for the future of the Jewish Brazilian community, in which mixed marriages were increasing. Also part of her concern was the kind of education Jewish parents were offering or denying their children. The article “Amigos” (Friends, in Aonde Vamos? December 30, 1965), for example, describes the visit of a couple of Jewish friends who had moved away from the city. They had chosen to educate their children as atheists, like themselves. During their conversation about this subject, the author maintained that such an attitude was unfair to their children, since the couple had themselves received a Jewish education and thus had the choice of rejecting it. In short, they were granted a chance that was being denied to their descendants. The friends responded that there would always be a “handy grandfather” if their children ever needed a Jewish orientation. The hostess-writer decided to refrain from answering this allegation, realizing that she and her old friends no longer spoke the same language.

Os Disperos

The Dispersed Ones conveys the same allegiance to Jewish ideals and to Zionism expressed in her newspaper articles. The seven short stories that comprise the book refer to several aspects of Judaism, contradicting the general notion that Jews are identical in thought and personality. In the title story, “The Dispersed Ones,” different outlooks on Judaism prevent a couple from becoming romantically involved. In “A visita do Embaixador” (The Ambassador’s Visit), an Israeli ambassador in Brazil visits a synagogue on the occasion of the celebration of Israel’s Independence Day. In a festive atmosphere, he is received by participants of both high and low rank; in the midst of all the excitement, a humble shammes (synagogue caretaker) approaches him with a letter. The ambassador takes the letter and opens it on his way back home. Written by the shammes’s son, it is addressed to his father, telling him about his joy of being in Israel as a fighter for its independence and about the imminent battle against the enemy. In Hebrew, however, perhaps unknown to the shammes, there is an official notification to the father of the fact that the letter was found among the dead son’s belongings, with the recommendation that it should be sent to his father.

Fishenfeld’s Zionist approach in this emotional story did not prevent her from viewing with a critical eye the society that received the ambassador and, by extension, the Brazilian Jewish community at large. Its petty ambitions, jealousies, and internal intrigues contrasted vividly with the humility of the shammes, whose son was indeed the only Zionist in the practical meaning of the word, since he was “there,” in Israel.

In “O Milagre” (The Miracle), the narrative voice is of a male traveler who recounts an encounter with a Jewish man from Cochin, India, waiting for the arrival from India of a woman he did not know personally. They would be meeting for the first time at an airport in Israel. The miracle was that in Israel old prejudices against skin color would be dissipated by love. (This short story was translated into English and published in Canada.)

In “O Primeiro Seder” (The First Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder), a Jew who had renounced his Jewish roots returns to them on A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover at the insistence of his descendants. “Esquecer” (Forgetting) conveys the issue of the Holocaust survivors receiving or not receiving German compensation for their losses. “O arenque” (The Herring) is a story told by a herring itself, allowing Fishenfeld’s humor to come through the narrative, while in “A eterna aliança” (The Eternal Covenant) his great-grandson’s circumcision ceremony leads a man to return to his past while the present is changing around him.

Janette Fishenfeld was the first, if not the only, Brazilian Jewish woman writer to display an adamant fidelity to Zionist idealism, while at the same time expressing an objective, though critical, view on the Jewish community in Brazil, its weaknesses, and its strengths.

Selected Works

Os dispersos (The Dispersed Ones, a collection of short stories). Niterói, Brazil: J. Fishenfeld, 1961.

Igel, Regina. “Janette Fishenfeld: ‘Imagens no meu espelho’ (crônicas).” In Imigrantes Judeus/Escritores Brasileiros, 144–146. São Paulo: Associação Universitária de Cultura Judaica, 1997.

Igel, Regina. “Brazilian Jewish Women Writers at the Crossroads.” In Passion, Memory, Identity, edited by Marjorie Agosín, 74–78. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Lispector, Elisa. “Em estilo fluente ...” (In a flowing style). In the inside cover of The Dispersed Ones. Niterói, Brazil: J. Fishenfeld, 1966.

Rozansky, Miriam. “Uma palavra sobre a autora” (A Word about the Author). In the inside cover of The Dispersed Ones. Niterói, Brazil: J. Fishenfeld, 1966.