Cuba

With the exception of a few crypto-Jews and businessmen who settled in Cuba during the Spanish era, the Jewish presence in Cuba began after the Republic of Cuba was established in 1902, as American Jewish businessmen moved to the new nation. The community grew with the arrival of Turkish and Eastern European Jews in the early twentieth century, fleeing internal strife in Turkey and antisemitism in Eastern Europe. Each of the Cuban Jewish communities had slightly different gender roles, but the women of all three were motivated activists, especially for Zionism after World War II. Members of the Jewish community gradually left Cuba, mostly for the United States, as Fidel Castro rose to power in the 1950s, though a small number still remain.

The Colonial Period

The history of Jewish women in Colonial Cuba is still wrapped in mystery. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia (1903): “Jewish women, forcibly baptized, and sent to the West Indies by the Spanish authorities, seem to have been among the early settlers [of Cuba].” The term “Jewish women” in this context needs explanation: In 1492, King Ferdinand (1452–1516) and Queen Isabella (1451–1504) of Spain signed the infamous edict that ordered the expulsion of all professed Jews from their kingdoms. Officially, there were no Jews left under Spanish rule, so that persons found to be secretly practicing Judaism were treated as Catholic heretics and handed over to the Inquisition. The converted Jews and their descendants were marked as conversos or New Christians, and remained a socially separate group, subject to legal discrimination. The popular use of the term “Jewish” with respect to colonial Latin America may refer to New Christians, regardless of the sincerity of their conversion, as well as to the crypto-Jews, who maintained their Judaism secretly.

The first stronghold of the Spanish Empire in America was erected in Hispaniola, and the second was Cuba, which was occupied in 1508. In 1512 Diego Colon (son of Columbus) wrote to the king of Spain that in the West Indies there are “many maidens of Castille, conversas” (Ortiz, 1953); these women were sent to the West Indies as wives for the settlers, in order to create a stable colonizing society. Many of the early settlers had typical Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic names. In 1518 the immigration of New Christians to the Indies was banned, but the local authorities disregarded the new laws, since many of the colonists abandoned the Caribbeans following the discovery of the rich empires in Mexico and Peru. The conversos, including those who professed their Jewish faith secretly, were able to lead a fairly peaceful life; distant from the centers of the Spanish government, they felt relatively safe from the long arm of the Inquisition.

In Cuba there was no Holy Office, and very few persons were burnt at the stake—none of them was accused of being a judaizer. A few crypto-Jews were discovered by the Cuban authorities throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and were sent for trial to the Inquisition in Cartagena (Colombia); apparently there were no women among these victims.

New Christians and crypto-Jewish women were gradually assimilated into the Catholic Creole society. Several aristocratic families preserved a vivid memory of their Jewish ancestry well into the twentieth century. Thus the descendants of Jewish women in medieval Spain became part of the sugar plantation aristocracy that emerged in the eighteenth century. These women inherited the conservative values of the traditional Spanish society in its attitude towards women and family life.

Women in Cuban Society

The white upper-class family on the eve of independence was patriarchal, with women totally dependent on men to protect and support them. Women had inferior legal status, and had no right to control their property unless they were widows. They were valued for their beauty, weakness and submissiveness—virtues that prepared them for marriage and for their duties as wives and mothers.

The church legitimized the submission of women by limiting their education to the management of their household, and by transmitting religious and moral values that imposed chastity on women while tolerating double standards for men, who were allowed to kill their wives for adultery but were not punished for having concubines. The church also controlled the only area in which women were able to participate in public life: They were involved in beneficent work under the auspices of Catholic charities.

At the other extreme of Cuban society were the black and mixed-race women, who could seldom enjoy the protection of men and had to work hard to support their children. Though slavery was abolished in the 1880s, it left its imprint on the Cuban society in the inferior status of people of color, as well as in the family structure, in which common union was more frequent than religious marriage. The presence of women of color in the labor force was much higher than that of white women; the majority were engaged in domestic services and agriculture.

The rebellion against Spanish domination (1895–1898) was also a revolution for a just and democratic society. The participation of women in the national cause marks the beginning of their own struggle for independence. With the establishment of the Cuban Republic (1902), the feminist movement started its long and slow process towards the achievement of legal rights. The separation of church and state and the growth of a secular educational network increased the literacy rate of the female population. Work “in the street” continued to be viewed as inappropriate for women in white affluent families. Gradually, however, unmarried middle-class women joined the labor force as teachers, nurses, and office workers. Lower-class women, white and women of color, worked also as seamstresses, laundresses, and cigar workers. Poor and illiterate women from the rural areas who moved to the capital often earned their living as prostitutes. The red light zone of Old Havana was also the first residence of many of the poor Jewish immigrants from Turkey and Eastern Europe.

American Jewish Women

Only a very few Jewish women lived in Cuba prior to independence; they came as the wives of Jewish businessmen from Curaçao and other Caribbean islands, who settled in Cuba during the nineteenth century without disclosing their religious identity. These women assimilated into the Cuban upper class and had but little contact with the Jewish community that was formed after independence.

The Cuban Republic was founded in 1902 under United States patronage. American firms were deeply involved in the development of the sugar industry and in exporting consumer products. In consequence, a large colony of American businessmen was established in Cuba, among whom was a small group of a hundred Jewish families.

The American Jewish women arrived in Cuba only after their husbands could supply a comfortable standard of living. Some of them had met their future husband when he returned to the United States to look for a bride. In Havana they lived in elegant neighborhoods and adopted the way of life of the local Americans and of the Cuban bourgeoisie.

American Jewish women enjoyed the advantages of spacious housing, cheap servants, and the prestige of being American. Their main role was to be devoted wives and mothers, but having domestic help allowed them plenty of spare time for social activities. They joined the social frameworks of other Americans—the Woman’s Club of Havana and the Mother’s Club. However, they preferred the company of their Jewish friends.

The Ezra Society was founded in 1917 as a women’s charity, affiliated with the United Hebrew Congregation that was formed in 1906 with the objective of purchasing grounds for a Jewish cemetery. The first task of Ezra was to collect funds for the victims of World War I and send them to Europe. With the arrival of poor immigrants from Eastern Europe in the early 1920s, the members of Ezra took responsibility for the women and children among the immigrants; they protected single women who arrived alone, took special care of pregnant women, and assisted young mothers. The philanthropic work of the American Jewish women, like that of upper-class Cubans, was directed towards an unprivileged feminine group and was an extension of their role as mothers.

The first president of Ezra Society was Mrs. Steinberg, who immigrated from Key West, Florida, with her husband Joseph shortly after independence. The leading philanthropist of the community was Jeanette Schechter, who was born in Palestine, immigrated to the US, and arrived in Cuba after her marriage in 1913.

The main organization of the American Jewish women was the Menorah Sisterhood, which was founded in 1927 as an auxiliary to the United Hebrew Congregation. The Sisterhood took a leading role in the religious life of the American community. Its members embellished the synagogue, organized services on Friday nights, and convinced the men to participate. Milly Weintraub, the first president of Menorah Sisterhood, and her husband Adolph were the first teachers in the Sunday school. On the fiftieth anniversary of the Congregation it was recognized that: “The Sisterhood nourishes religious loyalty among our children in their tender years inasmuch as the religious school functions under its aegis.”

The members of the Menorah Sisterhood, including those who were born in Europe, identified themselves as loyal Americans. They conducted their meetings and published their minutes in English and adopted American habits. Contrary to the custom in Cuba, where married women preserve the names of their parents, the American Jewish activists are recorded in the minutes and publications of their society as Mrs. Charles Shapiro, Mrs. Philip Rosenberg, Mrs. Nathan Heller, Mrs. Richard Knopke, Mrs. Henry Edelstein, etc., concealing their personal identity behind that of their husbands.

Sephardic Women

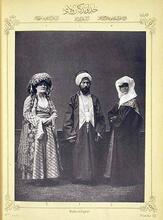

The majority of Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic women arrived with the second wave of immigration from Turkey, which lasted throughout the 1920s. The first wave of immigration was mainly male; it was motivated by economic reasons and by the fear of compulsory enlistment in the Ottoman army during the Young Turks’ revolution (1909) and the Balkan Wars (1912–1913). The young immigrants hoped to return home after “making America” or to bring over their wives or brides. However, the outbreak of World War I severed communications with their families.

The growth of the Cuban sugar industry during the first twenty years of the Republic opened new economic opportunities for the Sephardic immigrants, who dispersed throughout the island as itinerant peddlers. The largest group settled in Havana, in 1914 founding the communal organization Chevet Ahim, which supplied religious services to the whole Sephardic population. The years of World War I and its aftermath were a period of prosperity known as “The Dance of the Millions.” During that period, Sephardic men started to locate their wives and relatives in order to bring them to Cuba.

The women who remained in Turkey until 1920 struggled for survival throughout the long years of separation. They suffered from hunger, diseases, and other consequences of the war. Since men emigrated or were recruited to the army, women, children and old persons remained with no one to protect them, dependent on the generosity of relatives or on the aid of welfare agencies such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC).

After the war, communications with the old home were resumed and wives, children, mothers and other relatives from Turkey emigrated to Cuba to escape poverty and instability. Cuba became the destination of Sephardim from two distinct areas in Turkey: Istanbul and Thrace (European Turkey). Most of them came from two small towns: Silivri, in the outskirts of Istanbul, and Kirklareli (Kirklisse) near Edirne. The immigrants from these two towns comprised extended families that created informal networks of immigration in which women had an important role in assisting the newcomers.

The arrival of Sephardic women facilitated the establishment of a stable community, reuniting families and supplying brides for the marriage market. At the same time, however, the prices of sugar collapsed, and Cuba faced a severe economic crisis that affected the whole population. The new Sephardic immigrants were “no longer young adventurers in search of riches, but families and small children who fled from misery” (Bejarano, Rumbos, 1985). In view of the new requirements of the community, the Sephardic women took responsibility for the poor and needy.

A women’s Sephardic charity, La Buena Voluntad, was established in Havana as early as 1918, as an auxiliary of Chevet Ahim. It cared for widows and orphans, distributed food and clothing to poor families, and maintained direct contact with persons in need of assistance. Women in the interior towns did not institutionalize social assistance, but they created informal frameworks for mutual help: “In Camaguey, when a woman was sick, everybody went to watch over her day and night; when a woman gave birth, all the women took care of her, one day each. There was a real bikur holim (care of the sick); it was one big family” (Behar, 1991).

Sephardic women did not work outside their homes, but dedicated themselves to their household and their children. Coming from a Muslim country that was socially divided into different ethno-religious frameworks, Sephardic men and women considered it inappropriate for a Jewish woman to work in a shop and mix with the majority society. Their social life was limited to the family and to the community, and they transmitted to their daughters the idea of social seclusion as a means of Jewish continuity.

In Sephardic families, women were the agents of tradition and religion. In the provinces, where there were no Jewish schools, mothers were responsible for the religious education of their children. Women were considered more orthodox than men; they observed the SabbathSabbath laws even if their husbands went to work. Before the founding of synagogues, prayers were held in private homes, where women hosted the itinerant peddlers, especially during high holidays and for selihot. The traditional dishes served after services and during family celebration were an important element in transmitting Sephardic heritage.

Girls born in Cuba were sent to public school or to the day school of the Sephardic community. When they finished school they remained at home to help their mothers until they got married. An extraordinary case was that of Reina Perez, who dedicated her life to the education of Jewish children, together with her husband, David Perez, a devoted teacher who prepared Jewish children, Sephardic and Ashenazi, for high school. The level of education of Sephardic women gradually rose, but only after World War II did they start to study at university and to work outside their homes.

Eastern European Women

Immigration from Eastern Europe was a direct result of the United States Quota Acts (US Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924). The first women to arrive were victims of pogroms in the Ukraine, who appeared in Havana in 1921 in a deplorable state; the assistance of Ezra Society practically saved them from starvation. Immigrants were tempted to come to Cuba since travel agents promised them an easy passage from there to the United States. They found themselves without money in an unfamiliar environment, in a country stricken by economic crisis and unemployment. Jewish women from Eastern Europe were unaccustomed to the heat and to local conditions and were afraid to work in domestic service in a non-Jewish home. Considering their stay in Cuba as temporary, they depended on assistance from relatives in the United States or from the philanthropic agencies of the American Jews.

In 1924 the United States tightened its restrictions on immigration and Jewish welfare organizations expanded their activities in Cuba, aiming to convince the Eastern European Jews to give up their American dream and establish a new community in the island. The National Council of Jewish Women sent Cecilia Razovsky and Vera Shimberg to study the situation of the refugees in Cuba; their report was the basis of a broad project of social assistance that supplied working facilities, medical care, and communal organization. The representatives of the American welfare organizations were particularly concerned with the situation of young women who arrived in Cuba on their own without the protection of their families.

Many of the Jews who arrived in Cuba during the 1920s came from the regions of Grodno and Bialystok, which during World War I were trapped in the battlefield between Russia and Germany; after the war these regions became part of independent Poland. The young women, who had spent their youth in war and in wanderings, “had too little education, were disillusioned, bitter, disappointed [and] suspicious of social service” (Viteles, 1925).

The living conditions of these women were very poor; they suffered from malnutrition, the difficult climate, and loneliness. They crowded together in small unhealthy rooms near Havana’s red-light district, paying a monthly rent of five dollars per bed. Families shared their apartments with lodgers, with no separation between the sexes; the women suffered from lack of privacy but maintained a “high moral standard.” Jewish social workers sent from the US reported that there were no prostitutes among the Eastern European immigrants, and very few cases of unmarried mothers or abortions. The only Jewish prostitutes that were found in Havana were “professionals” brought over from the United States or Latin America.

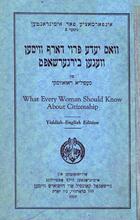

The Ezra Society was very helpful in assisting the immigrants, but the representatives of the welfare agencies from the United States criticized its philanthropic attitude and introduced professional methods of social assistance. They supplied sewing machines and raw material that enabled the immigrants to develop small workshops of clothing and shoes. Havana in the 1920s, like New York in the early 1900s, had its Jewish sweatshops, with young women employed by other Jews during long working hours, in suffocating heat, for a poor salary. Their difficult life was reflected in a number of stories published in the local Yiddish press.

The Yiddisher Zenter (Jewish Center), the main organization of Eastern European Jews, established the Meydlheym (Young Women’s Home) to protect Jewish women from falling into bad hands. The home was intended for young women who came to meet their future husbands, as well as for married women hoping for reunion with husbands with whom they had lost contact or to get a divorce. In 1928 a group of Jews of European origin and their descendants, including most of North and South American Jewry.Ashkenazi women founded the Froyen-Farayn (Women’s Organization), which assumed responsibility for managing the Meydlheym. The first president was Helena Goldstein, and among its active members were Anna Pincus, Esther Shaposhnick, and Sarah Loifer.

The Froyen-Farayn became the major female institution and one of the most successful Jewish organizations in the Eastern European sector. Its main objectives were to assist the needy and the sick, especially women and children, and unlike many of the other Jewish institutions, it was not torn by political rivalries. The Ashkenazi women also established the Kinderheym (Children’s Home), which sheltered orphan children and children whose parents were unable to maintain them. The Young Women’s Home gradually changed its functions to become the dwelling place of poor women, widows, and the elderly. One of the major activists of the Women’s Organization was Olga Shmidt, who had arrived in Cuba in 1924. In addition to her devotion to poor children and Jewish education, she was also active in the Committee Against Tuberculosis and Mental Disease, the second important charity of the Ashkenazi sector. During the revolution of 1933 Olga Shmidt organized a committee that distributed food to hungry Jews. Shortly afterwards, however, she received an American visa and emigrated to the United States. Her case reflects the main problem of the Cuban Jewish organizations, which could not consolidate their leadership due to the continuous stream of outgoing migration.

1933 Revolution

The 1933 revolution was a central event in Cuban history; its ideology was based on a nationalist revival, aimed at returning to the Cubans their rights over their homeland. Native workers were granted priority over aliens in the labor market. Jewish workers, displaced from their salaried occupations, were forced to become self-employed and established their own workshops. Jewish women were taken as partners in the family business, slowly improving their economic position and gradually moving into the middle class.

The deproletarization of Cuban Ashkenazi Jews increased the need for cheap credit to supply merchandise and working tools. The Froyen Farayn was the only Jewish institution that succeeded in establishing a loan fund for small merchants and industrialists. In 1937 its members founded the Ley Kasse (Loan Society), aiming to facilitate self-employment for the two groups under their auspices: unprotected women and orphan children. With time their Loan Society became a major economic institution in the Jewish community.

Ashkenazi women participated more in economic life and in public activities than their Sephardic and American sisters. They were represented among the early Jewish students, the first being the sisters Mary and Sarah Nemzow. A few Jewish girls studied music, performing to a Cuban audience; among them was Maria Binder, a young violinist considered a wunderkind in the early 1930s.

Several Jewish women were active in Jewish education, working as teachers in the Jewish schools. Most of them were responsible for the Jewish curriculum, but graduates of the Havana University worked as teachers in the Spanish sections of the schools. Ida Cohen, a graduate of a Tarbut school in Poland, attempted to transmit her Hebrew orientation in an educational environment that preferred Yiddish. In 1940 she opened her own school, but shortly afterwards she emigrated to Mexico, where she continued to teach Hebrew.

Holocaust and National Revival

Jewish women from Germany and Austria arrived in Cuba from 1938 on, seeking a temporary shelter while waiting for their immigrant visas to the United States. Since the refugees were not allowed to engage in remunerative employment, they depended on the support of the local branch of the JDC. Better educated and accustomed to a relatively high standard of living, they looked down upon the Ostjuden, veteran immigrants from Eastern Europe.

The local Americans, members of the Menorah Sisterhood, took the refugees under their auspices. Jeanette Schechter, Wilma Shapiro, and other members of the Sisterhood devoted all their energies to assisting the newcomers. While the refugees were interned in Tiscornia (the Cuban Ellis Island), they visited them regularly, supplying their small needs. They organized evening classes in Spanish and English, hosted the women in their synagogue, and organized a school for refugee children.

The office of the JDC was directed by Laura Margolies, a social worker sent from New York to protect the Jewish refugees, whose presence in Cuba created a public scandal and aroused antisemitic attacks. Maintaining a low profile, Margolies was successful in helping to keep an open door for the refugees until the arrival of the SS St. Louis, a German ship carrying more than 900 refugees who were denied entry by the Cuban authorities. In May 1939, the refugees on board the St. Louis returned to Europe and the gates of Cuba were closed; the 5,000 refugees sheltered on the island gradually emigrated to the United States.

Immigration resumed in October 1940 with the arrival of refugees from Western European countries occupied by Nazi Germany; many of them came from Belgium and Holland and were engaged in the diamond industry. Several Belgian Jews had been born in Poland; their higher social status, together with their common background with the Ashkenazi veterans, facilitated their integration in the local community as Zionist leaders.

Since the Cuban government was interested in developing the diamond industry, the Belgian Jews were granted special permission to establish diamond factories that prospered during the war. Though women were not employed in the diamond factories, the Belgian women were very active in the framework of the Zionist organization, creating their own Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) chapter. The life of the women refugees is reflected in Felicia Rosshandler’s novel, Passing Through Havana, which tells the story of the Western and Central European Jewish refugees from the perspective of an adolescent girl. Life in Cuba left a strong emotional imprint on their life, but it was only a transitory period.

The Holocaust had a tremendous impact on the local Jewish community, particularly on the Eastern Europeans who had lost all their relatives. However, it also effected the establishment of an alliance between Cuban feminist leaders and the Jewish cause. The writer and journalist Mariblanca Sabas Aloma refuted antisemitic attacks in the pages of the daily Carteles, expressing her solidarity with the suffering of the Jews. The lawyer Ofelia Dominguez Navarro was the director of the Department of War Propaganda, which condemned Nazi persecutions and defended the rights of the Jews to their own homeland. In 1944 she was appointed secretary of the Comite Cubano Pro Palestina Hebrea (Cuban Committee for a Jewish Palestine), a Cuban lobby of politicians and intellectuals that supported the Zionist cause, in which she was backed by various feminist organizations.

The 1940s were a period of economic progress that also affected the Jewish population. Families moved into better housing, and women were able to hire domestic servants and to free themselves from household chores. They sent their children to the university and hoped to grant them the stability and comfort that they themselves had been denied in their youth.

Zionism in Cuba

Jewish women became much more active in the Zionist organization, creating various chapters of WIZO, according to the origin of different groups. The first president of WIZO was Ida Kokiel, and among its activists were Eva Weissman, Dora Benes, Mina Hiller, and others. In the Sephardic sector, WIZO was considered an appropriate framework for married women, who were previously restricted to their family and community. Their president was Victoria Adouth, a devoted Zionist who remained an important Zionist-Sephardic leader with the reestablishment of the community in Miami after the Castro revolution.

Following World War II, Zionism and the State of Israel became the central issue in Jewish life. The Cuban community, divided between different political ideologies, nevertheless united in its support of the Jewish state, and its major activities were related to the national campaigns. The president of the Zionist Union of Cuba considered the women the major instrument for the “Zionization” of the Jewish community; WIZO became the largest Jewish institution and through its membership every Jewish home became part of the Zionist organization.

The younger generation participated in Zionist activities in the framework of youth movements, which granted women an equal place in their activities. Women were represented among the young leaders of Ha-Shomer ha-Za’ir who were trained in Israel, as well as among the pioneers who emigrated to Israel and settled in A voluntary collective community, mainly agricultural, in which there is no private wealth and which is responsible for all the needs of its members and their families.kibbutzim.

Cuban-born girls, both Ashkenazi and Sephardi, continued their studies at the University of Havana, graduating in the humanities, architecture, and pharmacology. One of the outstanding professionals was Ida Glazer de Castiel, who founded the Colegio Hebreo Moderno (Modern Jewish School), which combined modern pedagogic methods with traditional inspiration.

While Cuban Jewish women adopted the way of life of the Cuban middle class, which was largely influenced by American fashion and taste, they remained in social Jewish frameworks, segregated from the Cuban society that referred to them as “polacas” (Poles). During the 1950s, the University of Havana was a hotbed of revolutionary activity, but Jewish girls were not involved in political activities.

The Castro Revolution

The Castro revolution of the 1950s affected the Jewish community as part of the Cuban bourgeoisie. The nationalization of private business led to emigration, and ninety percent of the Jewish population gradually left, most of them for the United States.

The Jews who settled in Miami formed two Cuban communities—Ashkenazi and Sephardic—trying to reconstruct their former social life and preserve their Cuban-Jewish identity. Those who remained in Cuba had to adapt to the new order, but were able to retain their former institutions.

The revolutionary ideology was based on equality, but integration into the system meant alienation from any religious community. Very few persons were able to bridge between their Cuban and Jewish identities under the Communist regime. One of them was Adela Dworin, who now serves as vice president of the community.

The political and economic crisis of the 1990s motivated a movement of return to Judaism, in which men and women take an equal part. The new Jewish woman in Cuba, however, is more Cuban than Jewish.

Session on Cuban-Jewish Women for the Jewish Women's Archive's Global Day of Learning, in celebration of the launch of the Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, June 27, 2021. Featuring Ruth Behar in conversation with Judith Rosenbaum.

Interview with Isidoro Behar. Institute of Contemporary Jewry: 1991.

Bejarano, Margalit. “Chevet Ahim Annual Report for 1924.” In Rumbos 14 (October 1985): 110.

Bejarano, Margalit. La Comunidad Hebrea de Cuba: La memoria y la historia. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1996.

Kohler, Max, “Cuba.” In The Jewish Encyclopaedia, Vol. 4, New York and London: Funk and Wagnalls, 1903.

Levine, Robert M., Tropical Diaspora: The Jewish Experience in Cuba. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1993.

Ortiz, Fernando. “La fama postuma de Jose Marti.” In Jose Marti y la comprension humana, edited by Marco Pitchon. Havana: 1953.

Perez, Louis A., Jr. Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Rosshandler, Felicia. Passing Through Havana: A Novel of a Wartime Girlhood in the Caribbean. New York: St. Martin's Marek, 1984.

Stoner, K. Lynn. From the House to the Streets: The Cuban Woman’s Movement for Legal Reform, 1898–1940. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

United Hebrew Congregation, Temple Beth Israel, Golden Anniversary 1906–1956. Havana: 1956.

Viteles, Harry. Report on the status of Jewish immigrants in Cuba. New York: 1925.

Wartenberg, Hannah Schiller. “Cuban Jewish Women in Miami: A Triple Identity.” In Ethnic Women: A Multiple Status Reality, eds. Vasilikie Demos and Marcia Texler Segal. Dix Hills, New York: General Hall, 1994, 186–199.