Baghdadi Jewish Women in India

Baghdadi Jews, originating from Baghdad, Basra, Aleppo, and other Arabic-speaking parts of the Ottoman Empire, came to India in the late eighteenth century and forged important communities in Calcutta, Bombay, and Poona. Unlike Bene Israeli and Cochini Jews, who resided in India for centuries, Baghdadi Jews came as a business community during the British Raj. The Jewish community imbibed both Western and Indian cultural impulses. While Judeo-Arabic in orientation and religiously and culturally conservative, by the second half of the nineteenth century the Baghdadi elite started to assimilate to British ways, including education, language, and dress; the lower classes retained strong Judeo-Arabic cultural identity for longer. A boon for Baghdadi Jewish women was formal education for girls. In Calcutta, the Jewish Girls School created opportunities for women to enter professional fields including education, commerce, medicine, law, and politics. Jewish women were also trailblazers in the Indian film industry.

Origins and Dispersal of the Baghdadi Community

The “Baghdadi” community of India included Jews coming mainly from Baghdad, Basra, and Aleppo, but also from other Arabic-speaking parts of the Ottoman Empire. They were referred to as Baghdadi because they followed the liturgy of Baghdad, a center of Jewish learning. The first family arrived in Calcutta, the capital of British India, in the 1790s via Surat, a city in western India. Shalome Obadiah Ha Cohen founded a flourishing business with Calcutta as his base, and other members of this family joined him. Jews from other cities of the Middle East followed and prospered. By the early 1940s, the Baghdadi population of Calcutta stood at around 4000, increasing during World War II, when about 1200 Baghdadi Jews from Rangoon, many with family members or connections to Calcutta Jews, took shelter in 1942. Perhaps another 3000 Baghdadis lived in Bombay and Pune.

A confluence of global and national events resulted in many Baghdadis leaving India from the 1940s onwards. These included World War II, the Partition of India, Indian Independence, the formation of the State of Israel in 1948, and immigration opportunities to the United Kingdom and Australia. By the 1960s, there were fewer than 600 or 700 Baghdadi Jews in Calcutta, and the Bombay and Pune numbers also declined precipitously. By the 1970s, it was hard to sustain Jewish communal life. As of the early 2020s, there are barely 50 or so Baghdadi Jews left in India, many of them elderly.

Though the Baghdadis were in India for less than 200 years, they were an important economic and cultural force and left an indelible impression in Calcutta, Mumbai, and Pune. Baghdadi Jewish women, equipped with education and less constrained socially and culturally than most other Indian women, charted new professional opportunities for women in general. Several of the Calcutta Jewish women wrote memoirs and novels about the community. Sara Manasseh, a Baghdadi from Bombay who is an ethno-musicologist, researcher and performer, writes about the community’s musical traditions.

From Judeo-Arabic to a Judeo-British Identity and Lifestyle

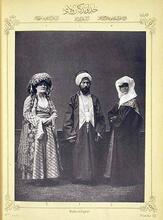

The ancestors of the Baghdadis had lived in the Middle East for centuries. They spoke Arabic, wrote Arabic in Hebrew script, and dressed in the manner of others in the Ottoman Empire. When they came to India, they continued those cultural traditions until the latter part of the nineteenth century. By the early 1900s, although still speaking Judeo-Arabic, with which they could communicate with their kinfolk and business relations throughout the East, most also were familiar with English and Hindustani.

By the mid-nineteenth century, both boys and girls were educated in English and community members became somewhat Anglicized in dress and language, while still strictly adhering to their core Jewish identity. Thus the “wrappers” (loose ankle-length, long-sleeved dresses with lace and frills) worn by the women gave way to dresses, just as the “dagla” (long coat), kamsan (long shirt), labsan (under shirt), and sadaria (undervest) for men gave way to trousers and shirts.

Anglicization was more pronounced among the elites and men. Until the mid-twentieth century, Baghdadi women wore wrappers at home. (Indian clothing was not adopted by the Baghdadis.) Despite being Anglicized, the Baghdadis were both comfortable and very familiar with the local cultures and mixed with the diverse communities of the multicultural port cities in which they lived. Baghdadi women, especially of the middle and poorer classes, were more home-bound, though friendly with their neighbors from many communities. One might hear Hindustani, Arabic, and English in their homes, with the addition of Bengali or Marathi in Calcutta, Mumbai, and Poona Baghdadi homes

Baghdadi Jewish food originally had many Arab elements, but in India, Muslim cooks employed in Jewish homes (because neither ate pig and they had some customs in common) taught their Baghdadi “memsahibs” to use Indian spices in their traditional dishes. There was much more Muslim and Hindu influence than British influence on Baghdadi Jewish cuisine. Baghdadi Jewish cooking was distinct from that of other Indian communities.

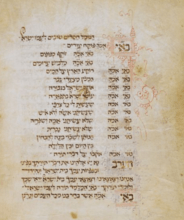

By the beginning of the twentieth century, affluent Baghdadi women decorated their homes in British fashion, as did other Indian and minority elites. Baghdadi brides shifted from arranged marriages to “love” marriages, and they began to wear modern western wedding dresses rather than the traditional “gowans.” The handwritten Arabic Marriage document (in Aramaic) dictating husband's personal and financial obligations to his wife.ketubbahs of the early eighteenth century gave way to more elaborate ketubbahs with painted colonial or other decorative motifs. By the twentieth century, the ketubbahs, titled Marriage Certificate Bond, were printed and written in English on one side and Hebrew on the other. Brides used the mikveh (ritual bath), often for the first and only time, just before their weddings, which were conducted in the synagogue. Western-style wedding receptions, in hotels or at home, included Western music and dance and often included a few Arabic music and dance items. Many Arabic Jewish foods were on wedding menus. Nahoums, an iconic bakery still located in Calcutta’s New Market, often catered the traditional Western tiered fruit cake with almond icing and other baked items for celebrations and festive occasions.

Consistent with Victorian morality as well as Arabic and Indian traditions, the morality and chastity of the women determined whether a family was “good” or “bad.” Until the mid-twentieth century, girls often married in their late teens or early twenties. As the community was so small, marriages were often arranged by family members from other port cities across the Baghdadi diaspora. Since these were micro-communities, the couples were often related. Until the early twentieth century, living in joint families were very common, but by the 1930s married couples typically moved into their own homes. Divorce was rare, as was polygamy. However, several wealthier Jewish men had Jewish mistresses as well as mistresses from other communities. Similarly, some Jewish women were mistresses of men from other communities.

During World War II, over 1000 American and British Jewish servicemen were stationed in Calcutta, and a few took home Baghdadi war brides. Several family members joined them, yet another way in which numbers dwindled. Though marrying non-Jews was “forbidden,” many intermarriages did occur, although it was frowned upon until the latter half of the twentieth century. Today, among the Jews left in Calcutta, many have intermarried, which complicates achieving an accurate count of the number of Baghdadi Jews left in India.

Until the early nineteenth century, girls studied at home, concentrating on Hebrew and Torah, with Arabic the main language of instruction. By the mid nineteenth century, girls and boys went to both Jewish and other denominational English-language schools. The girls took part in competitive sporting activities and competitions and in theatrical events. In Bombay, those Baghdadis who lived in and near Bycullah, a working-class neighborhood, attended the Sassoon Schools, which taught Hebrew and observed Jewish holidays. Most of the poorer and middle-class girls of Calcutta attended the Jewish Girls Schools, the boys the Elias Meyer and Talmud Torah Free Schools. The wealthier members of the community sent their daughters to private, often Christian-run schools that catered to the elites of all communities. The Calcutta Jewish schools are still operational, managed by Jewish community members, although no Jewish students attend.

Philanthropy

The Jewish community was exceedingly philanthropic and took care of Jewish community members in need and gave generously to religious causes in the Holy Land. The women, too, were involved in philanthropy. Flora Sassoon of Bombay was known for her philanthropic work, her engagement in family business, and her Hebrew and religious scholarship. In Calcutta, Mozelle Ezra (1853–1922), the daughter of Sir Albert Sassoon and the wife of community leader and philanthropist Elia Ezra, eased the poverty of the Jewish community and donated generously to synagogues and schools. In 1887, she established the Ezra Hospital—open to all communities but with special provisions for Jews—in honor of her late husband. She also contributed to supporting women, children, students, and other causes in Jerusalem, as well as to the maintenance of the tomb of Ezra in Iraq. Her son, Sir David Ezra (1871–1947), assumed his father's position in the community.

Lady Rachel Ezra (l877–1952), David Ezra’s wife and Flora Sasson’s daughter, continued in the tradition of her mother and mother-in-law. The matriarch of the Calcutta Jewish community, she presided over several of the community’s institutions as well as wider Bengali ones. Very supportive of all classes of the Calcutta community, she paid for many activities, such as weddings and sports. Her palatial home at 3 Kyd Street, which had its own zoo, became a community center where British and Indian officials met. She hosted Jewish activities, such as charitable events, wedding receptions, and Zionist youth functions. During the two world wars, Lady Ezra opened her home to allied Jewish servicemen and women stationed in Calcutta. The Ezras also took the lead in welcoming and rehabilitating European Jewish refugees, who started arriving in 1939. She and her husband contributed to Zionist causes. In 1947, the British government awarded her the Kaiser-I-Hind Gold Medal.

Fairly well-off women in both Calcutta and Bombay served as informal social workers among the poor. In Calcutta, the Jewish Women’s League was founded in 1913 and played an important role in social welfare activities. A similar league existed in Bombay, headed by Georgette Ani (1895–1975), who came to the city in 1919 as a bride. Ani was president of the Jewish Women’s League for many years, taking it upon herself to supply and oversee hot meals served daily to the students at the Sir Jacob Sassoon High School for Baghdadi Jews. She also supervised the serving of kosher meals in the Jewish ward of the J. J. Hospital and supported Youth Aliyah.

In Bombay, however, the Sassoon trusts, including those established by Lady Rachel Sassoon, weakened the incentive to form other organizations. The trusts provided poor girls with trousseaus to help them get married. Shahi Abraham (b. 1909), a former teacher, served as the managing trustee of the Sir Sassoon J. David Trust Fund in Bombay. She presided over donations of money, medicine, food, and clothing to Baghdadi and Bene Israel Jews. If necessary, she accompanied recipients to medical centers and hand-delivered money and medicine to their homes. Born in Calcutta, Kitty Sopher (1910–2001) came to Bombay after her marriage. A pillar of the Jewish community, she touched many young lives through Habonim (youth camps) in Matheran and Mahablishwar, which she organized and ran during school vacations. The camps emphasized Jewish studies and built team spirit; many Bombay Jews, now living all over the world, fondly recall these childhood memories. Hundreds of trees have been planted in Israel in Kitty Sopher’s memory and a library in her honor was established at Mevasseret Zion.

Employment: Trailblazers

Before the late nineteenth century, it was not considered proper for women to work outside the home, except as teachers and dressmakers. Flo Hayim (1910-2006), known as Madam Hayim, was synonymous with high fashion in Bombay. Born in that city, she grew up in Matheran Pedestrian Hill Station, where she and her sister apprenticed with the local darzi (tailor). An established couturière, Madam Hayim designed and made her own line of dresses in Bombay. Daily sewing classes in her house were attended by the elite of the city. Many of today’s leading dressmakers in India were her pupils. Although highly successful, Madam went out of her way to teach her craft to poor Jewish girls as a way of helping them to gain independence. Flo Hayim was versatile, informed, articulate, sophisticated, and well-traveled. She even owned her own horse, which she rode at the racecourse until her late seventies. In Calcutta, in the twentieth century, Maggie Meyer, who learned sewing abroad, was an exclusive dressmaker who catered to the elites of Calcutta society. She also taught dressmaking to elite housewives and fashionistas.

Many Baghdadi women became teachers, finding jobs in the Jewish schools as well as in Anglo-Indian or “convent” schools, and were well respected for their professional skills. Many Jewish women also provided tutoring in English. In Calcutta, Rahma Luddy, who received a Teachers’ Diploma from London, was the principal of the Jewish Girls School from 1929 to 1963. Under her leadership, it was considered one of the best high schools in the city and became a center of Jewish communal life. Miss Luddy introduced the teaching of modern Hebrew in the school in the 1930s; it eventually became a subject for the Cambridge External Examinations. She served the community in many other fields, including the Jewish Women’s League, the Judean Club, and the Young People’s Congregation, and was remembered with great respect and affection and honored by former pupils all over the world.

In Bombay, Mrs. E. Joseph became the headmistress of the Sir Jacob Sassoon Free School in 1925. Seen in the early years as a charitable institution for poor Jewish children, the school improved during her tenure. Enrollment increased and children from more affluent families began to attend. Another Baghdadi educator in Bombay was Sophy Kelly (1917–2002), who had also studied in England. Known as the Queen of Peddar Road, she was a pioneer educator, the founder and principal of the private Hill Grange High School, not a specifically Jewish school. She always wore a sari, which was unusual for a Baghdadi woman. She was president of the B’nai B’rith women’s auxiliary and had a close association with many political figures, including Nehru and Indira Gandhi. In 1965, she was appointed justice of the peace in Bombay. In 1985 she arranged for the president of India, G. N. Singh, to inaugurate the centenary celebration of the Knesset Eliahoo Synagogue in Bombay. Miss Kelly, as she was known, hosted many functions in her home, where her table was always laden with Baghdadi delicacies.

Baghdadi girls wanted to go to college to enter the professions. Secretarial opportunities were opened to women, and many Jewish women learned shorthand and stenography and became skilled secretaries. Their command of the English language made them valuable assets in British and Indian commercial firms. By the late 1930s, they began to work as secretaries for international firms or, in the 1940s in Calcutta, for the Allied forces, who employed many Baghdadi women. By 1947, perhaps a quarter of the Jewish women in Calcutta were active in economic and professional life. In Bombay, too, women were economically active. For example, Sameha (1889–1982), who was born in Baghdad, was sent to Bombay for an arranged marriage. When her husband turned out to be a gambler and a drunkard who abandoned her when she gave birth to their daughter, Sameha refused charity. She set out on her own, establishing herself as a Baghdadi pastry chef and specializing in baking machboz, a light pastry stuffed with cheese, dates and walnuts, in a clay oven, and in making feta cheese. Carrying the goods in a basket on her head, Sameha sold to most of the Baghdad households in Bombay from the 1950s to the 1970s. Eventually she became a matchmaker and moneylender. She helped her daughter emigrate to London, where she later joined her, continuing to bake machboz for Baghdadi families in London.

Despite the limited professional opportunities opened to women, Baghdadi women were path breakers, and the wealthier women entered non-traditional professions. Most impressive were the Guha sisters, Regina and Hannah Sen, daughters of a Baghdadi mother and a prominent Hindu lawyer who converted to Judaism. Regina studied law, and upon completing her degree, applied to be a pleader at the Calcutta Bar (1915), where a four-judge bench determined that pleaders could not include women. Her bid was followed in 1922 in Patna High Court, and again in the Allahabad High Court that enrolled Cornelia Sorabji as a pleader in 1921. Thus, Regina paved the way for women in law, though she did not live to enjoy the fruits of her efforts, as she died in her twenties.

It was Regina’s sister, Hannah, who had a long and distinguished career (1894-1957). Starting out as a teacher in the Jewish Girls School in Calcutta, she became the first Indian principal of the New High School for Girls in Bombay in l922. While earning her Teacher's Diploma from the University of London, Hannah Sen was closely associated with some of the leading British women's organizations. She gave many speeches, including one in front of many British Members of Parliament, on the conditions and problems of Indian women. In l932 she was asked to return to India to help found the Lady Irwin College of Home Science in New Delhi, of which she served as principal until l947. Under her leadership, this college was heavily involved in the Indian nationalist movement. Sen later worked with the Ministry of Relief and Rehabilitation, focusing on women and children who were displaced because of the partition of the sub-continent. She continued her interest in social affairs by representing India at international conferences of non-governmental organizations, UNESCO, and the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. Hannah Sen remained close to the Jewish community and contributed to the building of the synagogue in New Delhi.

There were other trail blazers among the Calcutta Baghdadi women. Rachel Ashkenazy was the first woman in the community to practice in the Calcutta High Court and pleaded for women in Purdah. Baghdadi Jewish women were among the first women in the dental and medical professions. The first woman doctor in the community was Rachel Duek Cohen, who enrolled at Calcutta Medical School in 1892. She was attached to the Jewish Baby Welcome Clinic that worked for poor and destitute children, an initiative of the Jewish Women’s League. Tabitha Solomon was among the first women to qualify as a dentist in India in 1928. Stella Benjamin, with a Masters degree from Calcutta University joined, the Bengal Chamber of Commerce and was the first woman to hold an executive position there. Many women had their own small business enterprises. In Bombay, Florence Haskell edited the Baghdadi newspaper Zion’s Messenger in the 1920s.

Movie Stars and Glamour

Despite parental and communal disapproval, several Baghdadi women, such as Sulochana (Ruby Meyers) (1907–1983), Ramola, Pramila (Esther Victoria Abraham), Rose, and Nadira (Florence Ezekiel, 1932–2006), became stars in early Hindi films, especially during the silent film period. Nadira was particularly known for her roles as a vamp. Esther (Pramila) became the first Miss India and her daughter followed in her footsteps. Naqi Jahan was crowned Miss India in 1967, the only mother and daughter to have that title. Esther also started her own film production company, Silver Films (1942). Mercia Solomon Mansfield (b. 1916) was active in British theater, television, and films. Pearl Padamsee (1930–2000), the daughter of a Baghdadi Jewish mother and a Christian who became the ambassador to Australia, promoted the “English theatre” in Bombay. She reproduced successful Broadway productions using local Indian talent. She directed, acted, and produced for the stage, schools, and organizations. Married first to a Bengali Hindu, then to a well-known Muslim personality, Pearl was a part of every English theater presentation. She raised the money for and established a successful rehabilitation center for drug addicts. In Bengali silent film, Rachel Sofaer (1907-1948), screen name Arati Devi, acted in the first silent Bengali film, Life Divine (1931).

Baghdadi Women Achievers Who Emigrated

As Baghdadi women settled across the world, they continued their professional lives, and several were very successful. Iris Morris Ferris (1910–1970) rose to the position of General Secretary in the London headquarters of the Girl Guides movement. Rina Einy (b. 1965) represented England in tennis in the 1984 Olympics. Sally Meyer Lewis was a professor of biology in the United States. Flower Silliman had the first kosher Indian restaurant in Israel (the Maharaja, in Jerusalem) and her daughter, Lahava Silliman is a well-known vegan chef. Jael Silliman and Maisie Meyer are academics who write about Baghdadi in India and Shanghai respectively. Sara Manasseh writes about and presents the music of the community, as does Rahel Musleah, a journalist, lecturer, and singer. The next generation of Baghdadi Jewish women continue to make waves, including Leemor Joshua-Tor in Biological Sciences at Cold Spring Harbor and Katya Pine as a music composer and musician in Canada. As time goes by, descendants of the Baghdadi Jews of India will no doubt make their mark in a variety of fields.

Betta, Chiara. “Marginal Westerners in Shanghai: The Baghdadi Jewish Community, 1845–1931.” In (eds.) New Frontiers: Imperialism’s New Communities in East Asia, 1842–1953, edited by Robert Bickers and Christian Henriot. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

Courter, Gay. Flowers in the Blood. New York: 1990.

Elias, Flower, and Judith Elias Cooper. The Jews of Calcutta: The Autobiography of a Community, 1798–1972. Calcutta: Jewish Association of Calcutta, 1974.

Ezra, Esmond David. Turning Back the Pages: A Chronicle of Calcutta Jewry. Vols. I and II. London: Brookside Press, 1986.

Hyman, Mavis. Jews of the Raj. London: Hyman Publishing, 1995.

Hyman, Mavis. Indian Jewish Cooking. London: Hyman Publishing, 1993.

Menasseh, Sara. Shbahoth: Songs of Praise in the Babylonian Jewish Tradition: From Baghdad to Bombay and London. London: Jewish Music Institute SOAS, 2012.

Musleah, Ezekiel N. On the Banks of the Ganga: The Sojourn of the Jews in Calcutta. North Quincy, MA: Christopher Publishing House, 1975.

Musleah, Rachel. Songs of the Jews of Calcutta. Cedarhurst, NY: Tara Publications, 1991.

Roland, Joan. The Jewish Communities of India: Identity in a Colonial Era. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 1998.

Silliman, Jael. Jewish Portraits, Indian Frames: Narratives from A Diaspora of Hope. Hanover and London: Brandeis University Press, 2001.

Silliman, Jael. The Man with Many Hats. Kolkata: Hyam Press, 2013.

Silliman, Jael. The Teak Almirah. Kolkata: Milestone Book, 2016.

Slapak, Orpa (ed.). The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities. Jerusalem: Israel Museum, 1995.

Solomon, Sally. Hooghly Tales. London: David Ashley, 1998.

Weil, Shalva, ed. The Baghdadi Jews in India: Maintaining Communities, Negotiating Identities and Creating Super-Diversity. London and New York: Routledge, 2019.