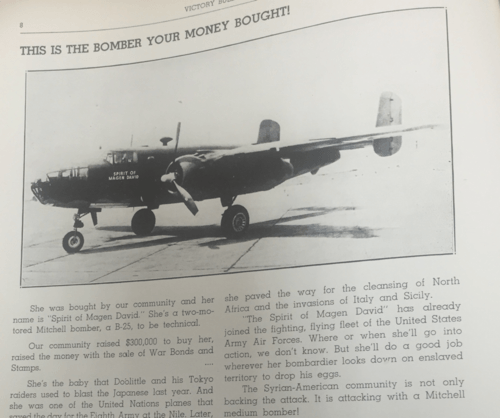

In October, 1943 the Victory Bulletin reported that the Syrian Jewish community of Brooklyn, New York purchased a two-motored Mitchell bomber for the United States Army Air Forces. They raised $300,000 for this acquisition through the sale of war bonds and stamps. This gesture points to a community with a strong support for the war effort and for their new home country (they began to settle and grow in American starting in 1907). The bomber was named “The Spirit of Magen David.” Magen David is a Hebrew term for the Shield of David and clearly contains some religious connotations. Magen David is also the name of one of the first synagogues built by this community and it later became the name of the community’s first Yeshiva. They contributed this bomber as both loyal Americans and as a distinct community with its own identity and symbols. The article ends with, “The Syrian-American community is not only backing the attack. It is attacking with a Mitchell medium bomber!” The community had a strong commitment to two different identities and seems to be threading the fine line that they created between them.

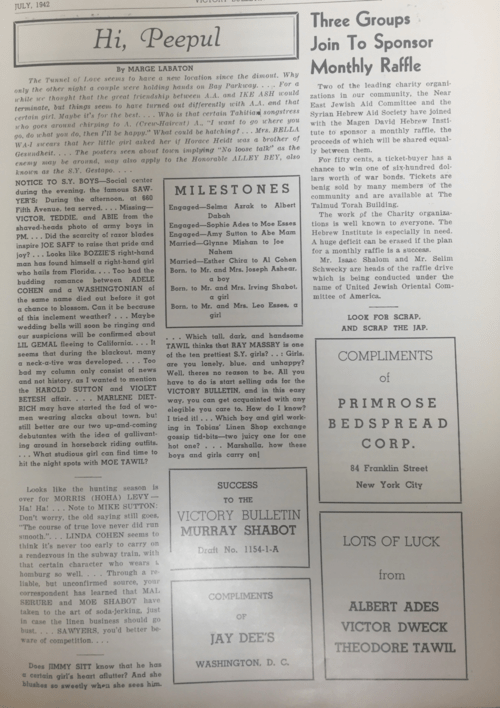

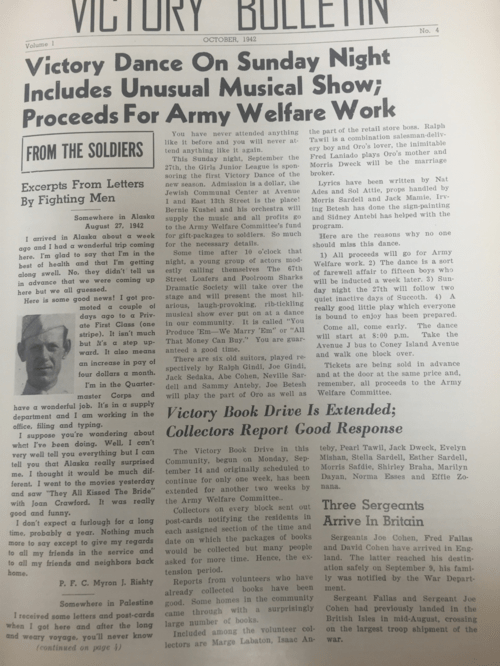

World War II, a traumatic event for all Americans, left its mark on the Syrian Jewish community of Bensonhurst in Brooklyn. As the men shipped off to war, the women began to organize at home in order to make their contribution to the war effort. The Girls Junior League (GJL), a social club created in 1940 for young women aged sixteen to twenty-five, soon became an organized group of second-generation American women committed to the war effort and to patriotic service. As part of this effort they put together a monthly newsletter, the Victory Bulletin, in order to print letters from soldiers, to write about current civilian defense projects and opportunities for involvement, to encourage participation in the war effort, to promote American values and the American President, and, to a lesser extent, to write about community gossip and events. The project symbolizes the dual identities of this community; these women were responding to the war as both Syrian-Jewish women and as American women.

The fact that these women were organizing, campaigning and publishing is astonishing because they believed that they belonged to a community that adhered to the notion that a “young girl’s place is in the home.” This was a novel endeavor for this group of women and the community they presented it to. Aware of the obstacles, these women worked extremely hard to succeed in the face of criticism. In a March, 1943 editorial of the Victory Bulletin, the women summed up the criticisms and extolled their accomplishments:

The cynics laughed and the community in general was just uninterested when the Girls Junior League was formed two years ago. But now, in March, 1943, no one can possibly deny that in a comparatively short period, the club into which our girls have organized has become a leading community organization- and in home-front, war work, the leading community organization.

The G.J.L., conscious of world events ever since its first days, has helped organize victory rallies, bond drives, Red Cross first aid classes, blood donor drives and campaigns for relief funds and clothing for our brave allies in Britain, Russia and China. Through this newspaper, which it established nine months ago, the girl’s club has kept interest high in these war activities and has encouraged and spurred on to greater effort the home-front fighters of our community.

These women felt a need to assert their value and importance to an audience that was often uninterested and even antagonistic. In order to gain respect they set out to do meaningful work within the community. They sought opportunities to present their community as a model American community, while ensuring that they remained a separate community with their own priorities.

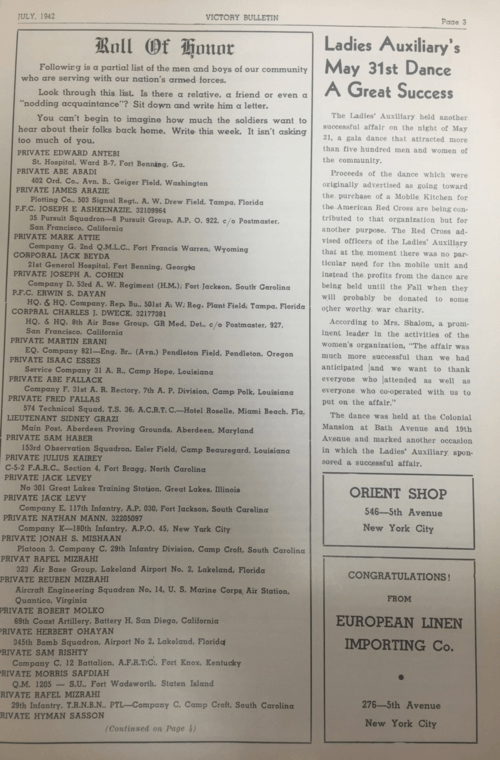

The Victory Bulletin focused primarily on community men who were serving on the front lines. The proportion of men sent to war from the Syrian Jewish community was a high of almost 1000 men out of a community of 6000. The first edition of the bulletin declares; “originally planned as a monthly bulletin to be sent only to the community’s boys on the fighting front, it has been expanded to the status of a community newspaper. The Victory Bulletin will be mailed monthly to every soldier from our community, no matter where he is stationed, as well as to every family here.”

The Victory Bulletin placed the Girls Junior League at the forefront of their community’s attempt to steer the course between Americanization and distinction. In the articles they wrote, the services they rendered, and the functions they organized they demonstrated how one could be American and yet maintain a unique communal identity. Like the bomber their community donated to the American air force, these women belonged to America and yet were proud to maintain the “spirit” of their community.