Women of the Carvajal Family

The Carvajals were a family of Hispano-Portuguese conversos in colonial Mexico whose trials for Judaizing heresy in the 1590s brought them fame and infamy as victims of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Their patriarch, Luis the Elder, was a sincere convert and conquistador, and his nephew, Luis the Younger, left a written record of his forbidden beliefs. However, most secret Jews among the Carvajals were women, from Guiomar Núñez, wife of the elder Luis, to her youngest niece, Ana. Their determination to create a Jewish identity in the home through prayer, observance of holidays, and culinary rites shows the importance of women to the survival of crypto-Judaism during the post-1492 Inquisition era, while also illustrating the intrafamilial tension this belief system caused.

History of the Carvajal Family

The Carvajals were a family of Hispano-Portuguese conversos in colonial Mexico whose trials for Judaizing heresy in the 1590s brought them fame and infamy as victims of prosecution by the Holy Office of the Inquisition. The patriarch, Luis de Carvajal the Elder (1539-1591), was a sincere convert and conquistador who fought successfully against English pirates and indigenous groups in New Spain (present-day Mexico). His nephew, the crypto-Jew Luis de Carvajal the Younger (1566-1596), left a written record of his beliefs at a time when crypto-Jews, or conversos who observed Jewish rites secretly, rarely dared do so. Yet most secret Jews among the Carvajals were in fact women, from Guiomar Núñez (d. 1582), the wife of Luis the Elder, to their youngest niece, Ana (Anica, 1579-1649). The determination of these women to create a Jewish identity in the home through prayer, observance of holidays, and culinary rites, among other practices, shows the importance of women to the survival of crypto-Judaism during the post-1492 Inquisition era.

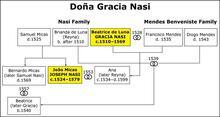

The Carvajals’ story unfolded against the background of Spanish imperial expansion and Inquisitorial efforts to eliminate heterodoxy, particularly the real or imagined heresies of New Christian converts of Jewish origin and their descendants. These two forces—imperialism and Inquisition—contributed to the trans-Atlantic crypto-Judaism of the Carvajals and the friction within the family that this identity caused, especially since not all members shared it. The estrangement of Guiomar from her husband, Luis de Carvajal the Elder, illustrates the effect of this friction. Guiomar was a Portuguese New Christian who met Luis because he may have worked in Lisbon in the 1560s with her father, Miguel Núñez, a participant in the slave trade of Spain and Portugal. She was also a secret Jew who subsequently refused to accompany her husband and his sister’s family to New Spain, due to his disinterest in the forbidden religion.

Although he was a Portuguese converso like Guiomar, Luis the Elder was a sincere Catholic focused on advancing his career. Working for the crowns of Portugal and then Spain, he had demonstrated administrative acumen, leadership, and valor in the Cape Verde Islands, Lisbon, Seville, and especially in New Spain. His exploits against English pirates led by John Hawkins in 1568 and the Chichimec indigenous people of the Mexican Caribbean coast during the 1570s convinced the Spanish king Philip II to grant Carvajal the governorship of the vast territory the conquistador had just pacified, the New Kingdom of León. The royal decree, issued in 1579, authorized Carvajal to bring 100 settlers and to name an heir to possessions he obtained in an area that stretched from northeast Mexico into present-day Texas. Most significantly, the charter included the anomalous provision that such individuals not be subject to an investigation of ancestry by which the crown typically tried to keep New Christians out of its colonies.

Unable to persuade his wife Guiomar to join the expedition, the newly appointed governor recruited his sister Francisca Núñez de Carvajal (1540-1596; no relation to Miguel Núñez above), brother-in-law Francisco Rodríguez de Matos (d. 1584), and their nine children to join him in the flotilla that sailed from Seville for Veracruz, New Spain, in 1580. Perhaps Luis the Elder felt that the family’s crypto-Judaism would be less threatening to his career in the more sparsely populated colonies. He also could hope to have greater control over his family’s practices there, especially were they to include secret Judaism. The governor was also concerned for his legacy, given that he and Guiomar were childless, a circumstance that led him to name Francisca and Francisco’s son Luis the Younger as heir. However, distance from the Iberian Peninsula served only as a temporary shield for the family’s secret Judaism, and ultimately it did not impede this forbidden belief system from dooming the career and perhaps the life of Luis the Elder.

For her part, Guiomar did not despair entirely of persuading her husband to take up crypto-Judaism during his governorship. Just prior to his departure with the rest of the family, she beseeched her eldest niece, Isabel de Carvajal (1559-1596), to look for an opportune moment for convincing Luis the Elder to live as a crypto-Jew in New Spain, even promising to join him if he did so. Guiomar felt an affinity for Isabel, especially after discovering that her niece was a dedicated secret Jew, as was her merchant husband, Gabriel Herrera, who died in 1580 just before the voyage to New Spain. Isabel indeed raised the matter with her uncle once they were in New Spain, but Luis slapped her across the face for suggesting such a dangerous idea and warned her never to do so again.

During the 1580s, while Luis the Elder fulfilled duties as governor that frequently kept him on the move, his relatives eked out a meager existence, with Luis the Younger, his brother Baltasar (b. 1562), and their father Francisco Matos working as traveling merchants of small household goods. When Francisco died in 1584, his family prepared his body for burial in accordance with Jewish funerary customs. A salve for the financial woes of the Carvajals appeared in the persons of Antonio Díaz de Cáceres and Jorge de Almeida, prosperous Portuguese New Christian merchants who married Catalina (1564-1596) and Leonor (1574-1596), respectively, in 1586. Both Díaz de Cáceres and Almeida were crypto-Jews to varying degrees, and Díaz de Cáceres must have known of the secret Judaism of the Carvajals due to his prior interactions with Governor Carvajal and Rodriguez de Matos. These were marriages of convenience that provided the men families and the women support; the spouses had not met beforehand and Leonor was only twelve years old.

The Judaism of the Carvajal Women

A century after the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain, women were better positioned than men to preserve basic tenets of Judaism in Spanish territories, as their primacy at home allowed them to create an identity visible to their families but not, hopefully, to outsiders. Like fellow crypto-Jews, the Carvajal women lived their proscribed faith in that confined space, through culinary practices, observance of key holidays, and a liturgy that, in their spiritual and geographic isolation, they believed approximated normative Judaism.

Given the need for secrecy and the appearance of sincere Christianity, much of the family’s secret Judaism consisted of a “doing by not doing,” particularly around food. Along with Luis the Younger, the women, especially Luis’ older sister Isabel, fasted regularly, often several times per week, and approximated the rules of kashrut by avoiding pork and slaughtering other animals by draining the blood and removing the sciatic nerve. The women fasted to seek divine pardon for living outwardly as Catholics and to commemorate biblical heroines such as Esther and, from the Apocrypha, Judith, both of whom they venerated for resisting oppression of Jewish identity. The syncretistic elements of their practices show the influence of the surrounding Catholic culture that the Carvajals were attempting to deny, especially in the self-denial their fasting entailed and their ascription of sainthood to Esther.

Living in homes in Mexico City that Catalina’s and Leonor’s husbands had purchased, the Carvajal women prepared for Sabbath as often as circumstances permitted. Likewise, they observed the three holidays most important to Iberian crypto-Jews: the “Great Day” in the fall, for Yom Kippur; the feast of Esther in March, for Purim; and the feast of unleavened bread (pan cenceño) later in the spring, for Passover. The bread they ate for this third festival was nearly indistinguishable from the corn flour tortillas commonly eaten in New Spain. These three holidays resonated with generations of secret Jews for their themes of repentance for forced conversion; resistance against persecution, led by Esther, a brave crypto-Jewish monarch; and divine redemption.

Crypto-Jewish liturgy generally consisted of oral expressions of Jewish identity rooted in the Bible, rather than in the teachings and commentaries of the Talmud, as well as aversion to prayers and rituals central to Catholicism (Yovel, 318-19). Except the Shema, the central prayer of Judaism, a version of which they recited in Hebrew, the Carvajals prayed in Spanish, chanting verses from Psalms, fragments perhaps from Daniel, and those that Luis the Younger himself wrote (Cohen, 135-36; Liebman, The Enlightened, 40-41). Isabel joined her brother Luis leading these prayer services, perhaps due to her higher level of education and a status derived from being a childless widow that enabled her to devote herself to the Jewish education of her younger siblings (Colbert Cairns, 596). This bold and rash dedication contrasted with her uncle Luis the Elder’s pragmatism, exposing an irreconcilable difference between faith and acceptance of the surrounding reality that threatened to split converso families.

The Inquisition Trials

In 1589, the viceroy of New Spain arrested Luis the Elder, perhaps because of a conflict regarding boundaries of the governor’s territories. Subsequently, Felipe Núñez, Luisa’s converso adjutant, denounced Luis’s niece Isabel to the Inquisition. Felipe, a relative of Luis’ wife Guiomar Núñez, surely felt conflicted because three years previously, Isabel had tried unsuccessfully to proselytize him even as she apparently rejected his amorous advances (Liebman, The Enlightened, 30). Now, fearing downfall because of his superior’s detention by royal authorities, Felipe denounced Isabel to the religious court as a way of bolstering his own security. Isabel’s testimony that both her uncle and her brother Gaspar, a Dominican friar, knew of but did not report their family’s Jewish practices led to Gaspar’s arrest and Luis’s transfer from the royal prison to the Inquisitorial one.

Similar testimony from Isabel prompted the arrest of her brother Luis the Younger and her mother Francisca shortly thereafter. Under torture or its threat, Francisca and Isabel confirmed Luis the Younger’s admissions about the Carvajals’ crypto-Judaism. The tribunal arrested those of Isabel’s siblings in New Spain at the time, even questioning her ten-year-old sister Anica. Facing confessions from each other that confirmed their Judaizing practices, the detained Carvajals had no option other than admitting the truth and beseeching the mercy of the tribunal. At the auto da fé, or act of faith, of February 25, 1590, inquisitors sentenced the entire family to various penances while simultaneously reconciling its members to the Church. Through the spectacle of this public sentencing, complete with a procession of heretics and a sermon, inquisitors showed the consequences of heterodoxy to victims and the populace at large. Thus, they ordered all the accused Carvajals except Gaspar to abjure de vehementi, “for vehement suspicion” of wrongdoing. Gaspar was made to abjure de levi, “for light suspicion,” and temporarily lost his priestly authority. The Holy Office also took away Luis the Elder’s governorship and sentenced him to exile from New Spain for six years; he died a broken man in the royal prison while awaiting transport back to Spain.

Upon the arrest of his wife’s family in 1589, Antonio Díaz de Cáceres fled to the Philippines and Macao in a hastily bought ship. Through 25 years spent in commerce and transatlantic trade, Díaz de Cáceres had developed useful connections in New Spain and elsewhere, one of whom must have alerted him to his own impending peril. After escaping from unsympathetic officials in both places in East Asia, he returned to New Spain three years later in the same ship, whose contents the Inquisition promptly seized, as a form of payment for the value of his wife’s estate (Cohen, 111-13, 186). A more practical man than Catalina, not averse to consuming pork while a Judaizer in other respects, Antonio advised her that uncompromising secret Judaism would end in death. To demonstrate the appearance of his own Catholic sincerity, Díaz de Cáceres refused to live with Catalina and their daughter Leonor after the family’s first trial, although he did provide for them and, together with Almeida, his other in-laws. This calculation proved only partially effective, as the Inquisition accused him of heresy in 1596, imprisoned and tortured him subsequently, and then surprisingly reconciled him upon at the auto da fé of 1601.

Even though the terms of their sentence and reconciliation dictated perpetual monastic imprisonment for Francisca and her Judaizing children, as well as wearing the sambenito, or penitential garb, their actual penance was considerably lighter, as was typical in Inquisition cases. Thanks to the advocacy of Leonor’s husband Jorge de Almeida, Francisca and her daughters received permission to move from convents to a house near the Colegio de Santa Cruz, a school for promising indigenous children where Luis the Younger was serving his sentence. Unfettered access to the library there, with its books on topics generally forbidden to a reconciled Judaizer, facilitated Luis’s recidivism. In contrast, his mother and sisters set up a chapel in their new home and resumed saying mass and eating pork. They probably would have lived faithfully as repentant conversos had Luis the Younger, incorrigible as ever, not insisted that they also relapse. In contravention of their reconciliation, Luis, his mother, and sisters resumed their forbidden practices for approximately four years. The women prayed throughout the day; fasted at least twice weekly; observed the Sabbath and other holidays, often donning finer clothes and reciting prayers Luis or they had composed; and followed Kosher customs for slaughtering fowl. Thanks to the lifting of the requirement to wear the sambenito, the family also envisioned traveling to a Sephardic community in Europe or to the Ottoman Empire.

Instead, however, the Inquisition’s ability to compel secret Jews to testify against each other unraveled the Carvajals’ near escape. Testimony coerced from his friend Manuel Lucena prompted the re-arrest of Luis in February 1595; shortly thereafter, the tribunal detained again his mother and sisters, in part thanks to descriptions of their Judaizing in Luis’s autobiography. Luis had written this work hastily in late 1594 or January 1595, just before the tribunal apprehended him a second time, and its overt expression of Jewish identity suggests the book was not meant for readership in New Spain. Rather, Luis apparently intended to send it to his brothers Baltasar and Miguel, who had already traveled to Italy and, subsequently, in the case of the latter, Salonica (Liebman, The Enlightened, 31, 51; Cohen, 265). Francisca, Isabel, Leonor, Catalina, and Luis the Younger were all burned at the stake after the auto da fé of December 8, 1596, as relapsos, or recidivist Judaizing heretics.

As for the other women in the family, Francisca’s daughter Mariana testified that she taught crypto-Jewish practices to her younger sister Ana. After being reconciled to the Church along with her mother and siblings at their first trial, she began to show signs of mental instability, for example speaking about the heretical conduct of her family and claiming she wished audiences with inquisitors of her own accord. Nevertheless, inquisitors sentenced her to the stake at the auto da fé of 1601, by which time they had deemed her sound of mind.

Ana survived this first wave of persecution by the colonial Inquisition when the tribunal reconciled her to the Church in 1601. However, she died accused of relapsing to Judaism during the second wave, the so-called Great Conspiracy of Portuguese New Christians of the 1640s, culminating in the auto da fé of 1649 in Mexico City, the largest such spectacle in colonial Latin America. Perhaps because Ana had lived as a secret Jew during the intervening four decades, fellow crypto-Jews asked her to fast for their dead and considered her a saint. Matías de Bocanegra, the Jesuit priest and Inquisition historian who chronicled the auto da fé of 1649, wrote that Ana chewed on paper at lunchtime to simulate eating when in fact she was fasting (123). Detained for six years while her trial dragged on, she was steadfast in her Jewish faith to the end, despite suffering from an increasingly painful cancerous tumor.

After Catalina’s arrest in 1595, her nine-year-old daughter Leonor de Cáceres, the only offspring of the five Carvajal children who would be executed in 1596 and 1601, lived with two Old Christian families until, in 1600, the Inquisition brought her, too, to trial. Now fourteen and a faithful Catholic, Leonor gave detailed information about how her father Antonio de Cáceres taught her Catholicism, while and her mother, aunts, and uncle Luis taught her crypto-Judaism. This spiritually bifurcated upbringing, in which she learned to recite Catholic prayers and to consider saints to be idols, illustrates the opposing forces pulling on secret Jewish families of the Inquisition era. After being reconciled to the Church in 1601, Leonor married, raised four children as a sincere Catholic, and in 1652 tried to revoke, albeit unsuccessfully, her admission of Judaizing a half century previously.

Guiomar, Francisca, and the Carvajal sisters on the one hand, and the Inquisition on the other, adhered to truths that could never accommodate each other. While the power of the Holy Office implacably condemned these women, their commitment to live as secret Jews undermined that power and assured remembrance of their spiritual choice and the ordeal they suffered because of it. Their example yields a fuller understanding of crypto-Judaism as a nuanced, complex, and contradictory faith that relied especially on women for its vitality and continuity.

Berman, Sabina. Heresy, in The Theatre of Sabina Berman: The Agony of Ecstasy and Other Plays, trans. Adam Versényi. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002. 118-63.

Bodian, Miriam. Dying in the Law of Moses: Crypto-Jewish Martyrdom in the Iberian World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Cohen, Martin A. The Martyr: Luis de Carvajal, a Secret Jew in Sixteenth Century Mexico. 1973. Albuquerque: Univesity of New Mexico Press, 2001.

Colbert Cairns, Emily. “Crypto-Jewish Faith and Ritual in Nueva España: The Second Inquisitorial Procesos of Isabel de Carvajal.” eHumanista 29 (2015): 592-605.

Costigan, Lúcia Helena. Through Cracks in the Wall: Modern Inquisitions and New ChristianLetrados in the Iberian Atlantic World. Leiden: Brill, 2010.

Gitlitz, David. Secrecy and Deceit: The Religion of the Crypto-Jews. 1996. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

Liebman, Seymour. The Enlightened: The Writings of Luis de Carvajal, el Mozo. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1967.

Liebman, Seymour. The Inquisitors and the Jews in the New World: Summaries of Procesos, 1500-1810, and Bibliographic Guide. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press, 1974.

Liebman, Seymour, ed. and trans. Jews and the Inquisition of Mexico: The Great Auto de Fe of 1649, as Related by Mathias de Bocanegra, SJ. Lawrence, KS: Coronado Press, 1974.

Perelis, Ronnie. Narratives from the Sephardic Atlantic: Blood and Faith. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016.

Yovel, Yirmihayu. The Other Within: The Marranos: Split Identity and Emerging Modernity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.