Tamar: Midrash and Aggadah

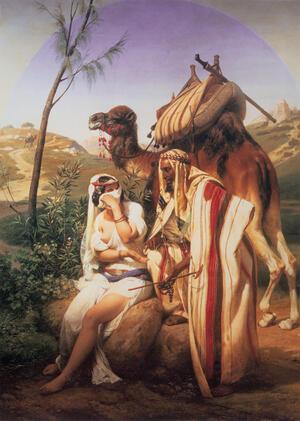

"Judah and Tamar," by Horace Vernet, 1840. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Tamar marries into Judah’s family, first to his son Er, and then to his son Onan after Er’s death. The Tamar narrative in the Bible casts the characters in a human, and not very complimentary, light. The later Rabbis sharply criticize Judah and his sons, but they describe Tamar positively, despite the fact that she is a convert. Her actions during her relationship with Judah demonstrate her purity, and her behavior shows the proper way in which all future women should perform. Judah sentences Tamar to death after finding out she is pregnant with his child, but Tamar stays silent, waiting for him to acknowledge his responsibility. Ultimately, Judah’s honesty rewards him much praise, and Tamar gives birth to twins, one of whom is an ancestor of David.

Introduction

The Tamar narrative casts the Biblical characters in a human, and not very complimentary, light. Judah’s son spills his seed rather than provide offspring for his brother; Judah does not keep his promise to give his younger son Shelah to his widowed daughter-in-law; and Tamar, whose husbands die one after the other, arrays herself as a harlot and sleeps with her father-in-law. Only at the last moment is Tamar saved from being burnt at the stake.

The Rabbis spare no criticism of Judah and his sons, pointing out the sins that were responsible for their bitter fate, but they display a different attitude toward Tamar. Although her behavior could be interpreted as an act of sexual licentiousness and wantonness, the midrashim defend Tamar and praise her. They describe her as a woman with sterling qualities, who maintained the strictures of modesty and faithfully observed the laws of Menstruation; the menstruant woman; ritual status of the menstruant woman.niddah. Tamar had been intended for Judah from the outset and she was a virgin when he engaged in relations with her. Their encounter on the way to Timnah was significant and decisive in the annals of the Israelite nation. Divine intervention was active throughout the entire incident: the hand of God directed Judah to the tent, and it revealed the pledge and thereby saved Tamar and her unborn children from the stake. Thus, Perez and Zerah came into the world, King David was descended from Perez, and the Messiah eventually will be born from this line.

Tamar's Marriages to Er and to Onan

According to the Biblical account, Tamar was most likely a Canaanite. The A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash is relatively silent on her life before she married into the family of Judah. One tradition asserts that she was an orphan and was converted in order to marry (BT Suspected adulteressSotah 10a), while another claims that she was the daughter of Melchizedek, king of Salem, who was “a priest of God Most High” (Gen. 14:18). Consequently, Judah judged her according to the laws pertaining to the daughter of a priest (which are set forth in Lev. 21:9) and ordered that she be burnt when he thought that she had become pregnant as a result of an illicit tryst (Gen. Rabbah 85:10).

Tamar was married to Judah’s firstborn Er and after his death she was given in matrimony to his second son, Onan. The midrash relates that Er was seven years old when he married Tamar (Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.Seder Olam Rabbah 2). The Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah declares that Er was “displeasing to the Lord” and was accordingly put to death (Gen. 38:7), while his brother Onan died because he did not want to do his duty as a brother-in-law, and rather spilled his seed on the ground (vv. 9–10). The Rabbis suggest that Judah’s two sons died because they engaged in unnatural intercourse with Tamar. Er acted in this manner so she would not become pregnant, for he feared that pregnancy would detract from her beauty, while Onan did so because he knew “that the seed would not count as his” (v. 9). Consequently, Tamar was still a virgin after the deaths of the two brothers (BT Yevamot 34b).

In another midrashic exegesis, the death of his two sons was a punishment for Judah, who had deceived Jacob by telling him that Joseph was dead. God said to Judah: “You have no children, so you do not know the grief at their loss. You deceived your father and told him that your son had died—by your life, you shall take a wife and bury your children, so that you will know the sorrow that comes from the loss of children” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayigash 10).

Yet another tradition views their death as punishment for Judah’s starting something but not finishing it. Judah persuaded his brothers not to kill Joseph, and instead sell him to the Ishmaelites (Gen. 37:26–27), but he did not bring this to a conclusion, since he could have completely saved Joseph: he should have carried Joseph on his shoulders to his father. He therefore was punished by having to bury his wife and his two sons, and also by coming down in the world, as it is said (Gen. 38:1): “Judah left [va-yered, literally, went down (from)] his brothers” (BT Sotah 13b; Gen. Rabbah 85:3).

The latter two traditions link the story of the sale of Joseph with the episode of Judah and Tamar, which are sequential in the Torah. Further to this juxtaposition, the midrash states that while the other brothers were engaged in the sale of Joseph, and Jacob was occupied by his sackcloth and fasting (over the presumed death of Joseph), Judah was busily engaged in taking a wife, and God was engaged in creating the light of the Messiah (who will eventually issue from the union of Judah and Tamar) (Gen. Rabbah 85:1). This midrash teaches that people are involved in their own affairs and troubles and do not see the sweeping divine plan that takes form before their very eyes, one that is for their own good and that gives them a future and hope.

Judah meticulously observed the laws of Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).yibbum (levirate marriage), and when his firstborn son died childless, he ordered Onan to marry his dead son’s wife Tamar, to “establish the name” of the deceased. (Deut. 25:5–10). The Rabbis find Judah’s conduct praiseworthy: even though the Torah had not yet been given, he nonetheless took care to observe all the commandments (Lev. Rabbah 2:10).

Tamar and Judah

Following the death of his two sons, Judah tells Tamar: “Stay as a widow in your father’s house” (Gen. 38:11), which the midrash reckons she did for one year. An additional year passed until the death of Shua’s daughter (Seder Olam Rabbah 2). The Rabbis deemed Judah’s marriage to the daughter of Shua the Canaanite to be an act of betrayal of the way of the Patriarchs and a moral decline; some even perceived her death as punishment to Judah for the sale of Joseph (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 9).

The Torah relates that when Tamar realized that she would not be given to Shelah, she planned how she would become pregnant by Judah and “sat down at the entrance [be- petah] to Enaim [einayim, literally, “eyes”]” (v. 14). The midrash tells that Tamar cast her eyes to the portal [petah] to which all eyes are cast (i.e., she cried out for help), that is, God, and said: “May it be Your will that I not leave this house empty” (Gen. Rabbah 85:7). Tamar’s prayer to God reveals her true aim, which, according to the Rabbis, was to cleave to the house of Judah and provide a successor for his line.

Some Rabbis sought to identify “petah einayim” with the Biblical Enam mentioned in Josh. 15:34. Another exegetical approach argues that this is not a place name, but rather describes Tamar’s manner of sitting. She opened the flaps of her tent on all four sides, as had Abraham, and like him she sat at the entrance and gazed (with her “einayim”—eyes) in every direction. This midrash, which compares Tamar’s behavior to that of Abraham, views the erection of her tent positively and sees it as reminiscent of Abraham’s exemplary hospitality.

Another Rabbinic exegesis understands “einayim” symbolically: Tamar gave eyes to her words, that is, she gave convincing replies to Judah, showing him that she was permitted to him. When Judah asked to consort with her, he inquired: “Perhaps you are a Gentile?” She replied: “I am a convert.” When he asked her: “Perhaps you are a married woman?” she answered: “I am unmarried.” He asked: “Perhaps your father received the money of betrothal for you [and you are already a married woman, without your knowledge]?” She rejoined: “I am an orphan.” He further probed: “Perhaps you are [menstrually] impure?” She answered: “I am pure” (BT Sotah 10a). This midrash presents Judah as meticulous in his observance of the laws regarding married women and niddah, even with a prostitute by the roadside. Tamar is portrayed as a woman who meets all the requirements of The legal corpus of Jewish laws and observances as prescribed in the Torah and interpreted by rabbinic authorities, beginning with those of the Mishnah and Talmud.halakhah: she is a convert, both unmarried and not betrothed, and also pure. In a similar interpretive direction, the midrash relates that, at first, Judah did not pay any attention to Tamar, thinking her to be a harlot. When he passed by her, however, and saw that she covered her face, he realized that she was not a strumpet, because such women do not veil their faces, and then he turned aside to her (Gen. Rabbah 85:8).

The Rabbis devote much attention to the geographical description, to which they impart moral significance. Gen. 38:13 states that Tamar was told: “Your father-in-law is coming up to Timnah for the sheepshearing,” thus implying that Timnah was a high place. The Samson narrative, in contrast, states that “Samson went down to Timnah,” thus indicating that it was a low place. The Rabbis reply that this is a moral description. Samson disgraced himself in Timnah, (since he went there in order to marry a Philistine woman), and therefore the Bible uses the language of descent, while Judah was exalted there (for being the forebear of kings; see below), and therefore the language of ascent is applied to him (BT Sotah 10a; Gen. Rabbah 85:6).

Gen. 38:15 tells that when Judah saw Tamar sitting by the roadside, “he took her for a harlot, for she had covered her face,” which she did so that her father-in-law would not recognize her. The midrash reverses Tamar’s uncovering and veiling of her face. It is inconceivable that Judah thought her to be a harlot because she covered her face, since, if anything, prostitutes show their faces. Rather, out of modesty, Tamar had always covered her face in her father-in-law’s home. Thus, when she disguised herself as a harlot and revealed her face, Judah did not recognize her (BT Sotah 10b). This midrash amplifies the positive qualities of Tamar, who generally comported herself extremely modestly. It was uncharacteristic of her to behave as a harlot, and she did so solely for the exalted purpose of establishing the name of her dead husband and bearing the predecessor of the royal line. The episode in the tent symbolically reveals Tamar’s true countenance, disclosing her concealed inner intent, which was completely pure. The encounter between Judah and Tamar, which would result in the birth of the Messiah, was performed with no external covering.

The Rabbis add that we learn from this incident that every daughter-in-law who conducts herself modestly in her father-in-law’s home will be privileged to bring forth kings and prophets, as did the actions of Tamar, from whom came forth kings—King David—and prophets—Isaiah the son of Amoz (there is a Rabbinic tradition that Amoz, the father of the prophet Isaiah, and Amaziah, king of Judah and a descendant of the Davidic line, were brothers) (BT Sotah 10b).

The Rabbis emphasize the hand of Divine Providence in Judah’s turning aside to the tent of Tamar. Judah wanted to pass by her, without entering the tent. What did God do? He summoned for him the angel responsible for desire. He [the angel] asked him: “Where are you going, Judah [i.e., why are you passing by the tent]? From where kings stand? From where redeemers stand? [i.e., you should enter the tent, from where kings and redeemers will come forth].” Only then did he “turn aside to her” (v. 16), against his will (Gen. Rabbah 85:8).

Another midrashic account has Judah saying: “This one is a harlot; of what concern is she to me?” and continuing on his way. Once he had passed by, Tamar raised her eyes to God and said: “Master of the Universe, am I to go forth with nothing from the body of this righteous one?” Then God immediately sent the angel Michael to bring Judah back (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 17).

The midrash notes that Tamar was still a virgin when Judah came into her. A woman is usually not impregnated from her first act of intercourse, but she broke her hymen with her finger, so that she would become pregnant (BT Yevamot 34a).

The Pledge

The Bible has Tamar asking Judah for a pledge, and, after his asking what to give her, “she replied, ‘Your seal and cord, and the staff which you carry’” (v. 18). The Rabbis say that she spoke with the spirit of divine inspiration (ruah ha-kodesh), for she would in fact receive these three items from Judah: “Your seal [hotamkha]”—this is kingship, for their descendants would include King Jeconiah son of Jehoiakim, of whom it is said: “a signet [hotam] on my right hand” (Jer. 22:24); “and cord”—this is the Sanhedrin, whose members are distinct, like the cord of tekhelet in the zizit [one of the eight cords of the fringe (zizit) at the corners of one’s garment must be of tekhelet, a special blue color—Num. 15:38]; “and the staff [u-matekha]”—this is the anointed king, the Messiah, who will issue from this union, and of whom it is said: “The Lord will stretch forth from Zion your mighty scepter [mateh]” (Ps. 110:2) (Gen. Rabbah 85:9).

Some midrashim argue that the embarrassing situation in which Judah found himself was punishment for selling Joseph. Tamar vanished, together with the pledge that Judah left with her, and he could not find her when he sent her the kid from his flock. God said to him: “You deceived your father with a kid [when you dipped Joseph’s coat of many colors in the kid’s blood, so that Jacob would think that his son was dead]—by your life, Tamar deceives you with a kid!” (Gen. Rabbah 85:9).

As Judah deceived his father by means of clothes, so, too, did Tamar similarly lead Judah astray with clothing. God said to Judah: “You told your father: ‘Please examine it [, is it your son’s tunic]’ [Gen. 37:32]—by your life, you shall hear ‘Examine these [: whose seal and cord and staff are these?]’ [Gen. 38:25]” (Gen. Rabbah 84:19).

The Rabbis learned from the Biblical account in Gen. 38:24, in which Judah became aware of Tamar’s pregnancy three months after their liaison, that a fetus is not noticeable in its mother’s womb for three months (Gen. Rabbah 95:8). Another tradition claims that Tamar made no effort to hide her pregnancy; on the contrary, she would pat her stomach and proclaim: “I am pregnant with kings and redeemers” (Gen. Rabbah 85:10).

When Judah heard that Tamar was with child by harlotry, he ordered: “Bring her out and let her be burned” (v. 24), but at that juncture she displayed the proofs the distinctive objects that were the pledge that Judah had entrusted with her. V. 25 states that she was “brought out [muzet],” which the Rabbis connected with the finding of a lost article (mezi’at avedah): Tamar had lost her proofs, and God provided others in their stead (Gen. Rabbah 85:11). A similar tradition avers that Samael (the Adversary) concealed the proofs, and God sent the angel Gabriel to find them. According to the Rabbis, this moment is depicted by David (Tamar’s descendant) in Ps. 56:1: “For the leader; on yonat elem rehokim [or: the silent dove of those who are far off]. Of David. A mikhtam.” When Tamar’s proof vanished, she was like a silent dove. God, however, intervened, on account of “Of David. A mikhtam,” for she was destined to be the forebear of David, who would be meek (makh) and perfect (tam) to all (BT Sotah 10b). These traditions stress the real dangers facing Tamar and her fetuses, and the fact that God miraculously intervened to ensure the existence of the future king.

When Tamar sent the proofs, that is, the pledge, to Judah, she said to him (v. 25): “I am with child by the man to whom these belong.” The Rabbis observe that she did not say outright: “I am pregnant by you,” from which they conclude that if Judah had not acknowledged his responsibility, Tamar was prepared to be burnt rather than publicly shame him. The Rabbis learn from this act by Tamar that it is better for a person to cast himself into a fiery furnace than to publicly shame his fellow (BT Sotah 10b).

"She Is More in the Right than I"

The Torah relates that Tamar did not publicly declare that she had been impregnated by Judah. Even when he sentences her to death, she sends him the pledge and does not spell it out. Judah must therefore decide whether to admit his responsibility and save Tamar from the pyre, or to sacrifice Tamar and preserve his honor. Since Judah was in a position of power, he could decide whether Tamar would live or die.

In the midrashic account, Judah initially denied all responsibility. When Tamar said: “Examine [or, acknowledge] these,” she used the wording “na” (please). She said to him: “Please acknowledge the countenance of your Maker, and do not hide your eyes from me” (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 17). This midrashic tableau has Tamar trying to arouse Judah’s compassion, while in another midrash, she threatens him: Tamar tells him: “Please acknowledge the countenance of your Maker. These proofs are yours, and they are your Maker’s” (since God took care to find the proofs that had been lost) (Gen. Rabbah 85:11). She thereby hinted to him that the hand of God was in this, and that Judah would obstruct the divine plan if he were to have her executed.

Judah confesses and declares: “She is more in the right than I” (v. 26). The Rabbis praise his courage for admitting to his acts and not fearing for his honor. The midrash says that by this act Judah publicly sanctified the Name of God and therefore merited having the Tetragrammaton included within his name (BT Sotah 10b). Another tradition relates that Judah was awarded the throne for having made this admission. He was not given the scepter because he was more heroic than his brothers, for others were just as valorous, but because he rendered true judgment and stated the truth.

In consequence, God elevated him over his brothers (Ex. Rabbah 30:19; Mekhilta de-Rabbi Ishmael, Masekhta Va-Yehi Be-Shalah 5). In yet another tradition a heavenly voice goes forth and proclaims: “You saved Tamar and her two children from the fire—by your life, by your merit I will save three of your children from the fire,” namely, Hananiah, Mishael and Azariah (BT Sotah 10b). An additional midrashic exposition states that because Judah was not too ashamed to confess, he merited the life of the World to Come (BT Sotah 7b).

Judah’s behavior, exemplary already in his own time, served as a sterling example for future generations. The midrash tells that when Reuben saw Judah confess his sin, he immediately admitted that he had desecrated his father’s couch (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 17; see Gen. 49:4). The Rabbis learned from Judah’s actions that if a person is shamed in this world, he will not be shamed before God in the World to Come (Ex. Rabbah 30:19).

In his blessings to his sons, Jacob blesses Judah (Gen. 49:8): “You, O Judah, your brothers shall praise,” which the rabbis view as an allusion to the episode with Tamar. Jacob is saying: Since you confessed, your brothers shall praise you in this and the next worlds. Jacob’s blessing was fulfilled, and thirty kings came forth from him: from David and Solomon to Jehoiachin and Zedekiah (the entire line of Judean kings). And so it will be in the World to Come, of which it is said (Ezek. 37:25): “with my servant David as their prince for all time” (Gen. Rabbah 97:8).

According to some exegeses, the statement “She is more in the right than I” was not uttered by Judah. In one tradition, God appears before the court of Shem. Judah said, “She is more in the right,” and God said: “than [or: from] I [or: Me]”—this is from Me (Gen. Rabbah 85:12). A similar tradition has a heavenly voice go forth and say: “These hidden secrets went forth from Me”: this entire episode was from God, because kings were destined to issue from Judah.

The midrash tells that Judah inherited the ability to recognize the other (le-hodot) from his mother Leah, who had said at his birth: “This time I will praise [odeh] the Lord” (Gen. 29:35). The Rabbis characterize Leah by saying that she “possessed the art” of such recognition, which she passed on to her children. Judah acknowledges: “She is more in the right than I"; David is similarly recognizant of God (Ps. 107:1): “Praise [hodu] the Lord, for He is good"; as is Daniel (a descendant of the Davidic line) in Dan. 2:23: “I acknowledge [mehode] and praise You” (Gen. Rabbah 71:5). This exegesis emphasizes the significant role of the mother in setting a positive example for her children, and her enduring influence on them.

Twins

The midrash tells of two women who veiled themselves and gave birth to twins: Rebekah and Tamar. The former covered herself with a veil when she saw Isaac in the field: “So she took her veil and covered herself” (Gen. 24:65), and she bore him Esau and Jacob (25:24); and Tamar concealed herself from Judah with a veil: she “covered herself with a veil and, wrapping herself up” (38:14), and she gave birth to his twins, Perez and Zerah (38:27) (Tanhuma [ed. Buber], Vayeshev 17). This midrash seeks to reveal the similarity between Tamar and the Matriarchs, the mothers of the Israelite nation, and thus show the propriety of her actions. Covering oneself with a veil is deemed to be an act of modesty, the reward for which is the blessing of offspring. The birth of twins was rare in antiquity and was therefore considered to be a special gift from God.

The Rabbis take note of the plene spelling of the word te’omim (twins) in the verse (27) referring to Tamar: “there were twins in her womb,” while this word appears with defective spelling in the verse that speaks of Rebekah’s twins. (“there were twins in her womb”—Gen. 25:24). The spellings differ because of the moral character of the twins. Rebekah gave birth to Jacob and Esau, one of whom was righteous and the other wicked, with the consequent deficient spelling. On the other hand, both of Tamar’s children, Perez and Zerah, were righteous, and therefore no letter is missing from the word “te’omim” in their verse (Gen. Rabbah 85:13).

Gen. 38:26 relates that after Judah learned that the harlot was his daughter-in-law Tamar, “he was not [yasaf] intimate with her [le-da’atah, literally, to know her] again.” The Rabbis deduce that three statements were made, each by a different speaker. Tamar said: “[Please] examine”; Judah admitted: “She is more in the right than I”; and the voice of God declared: “he was not intimate with her again” (T Sotah [ed. Lieberman] 9:3). The voice of God expressed in the present what the future held. Neither Judah nor Tamar knew what would later happen, but God did.

A different tradition interprets the verse in reverse fashion. Since Judah knew that Tamar acted for Heaven’s sake (le-da’atah, literally, according to her mind), he did not disengage from her that is, from that day Tamar became his wife in all respects (BT Sotah 10b).