Tamar: Bible

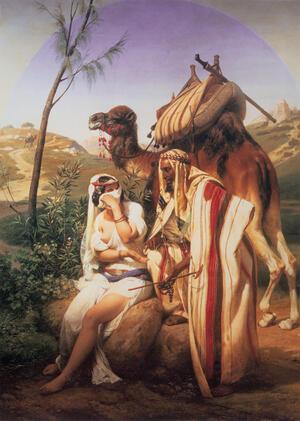

"Judah and Tamar," by Horace Vernet, 1840. Via Wikimedia Commons.

The story of the life of Tamar appears in the ancestor narratives of Genesis. As Judah’s daughter-in-law, Judah believes she has killed two of his sons, and subjugates her so that she is unable to remarry. However, she ultimately tricks Judah into impregnating her and therefore secures her place in the family. She gives Judah two sons, and her story illustrates her loyalty and her willingness to be assertive and unconventional.

Marriage and Widowhood

Tamar, whose story is embedded in the ancestor narratives of Genesis, is the ancestress of much of the tribe of Judah and, in particular, of the house of David. She is the daughter-in-law of Judah, who acquires her for his firstborn son, Er. When Er dies, Judah gives Tamar to his second son, Onan, who is to act as levir, a surrogate for his dead brother who would beget a son to continue Er’s lineage. In this way, Tamar too would be assured a place in the family. Onan, however, would make a considerable economic sacrifice. According to inheritance customs, the estate of Judah, who had three sons, would be divided into four equal parts, with the eldest son acquiring one half and the others one fourth each. A child engendered for Er would inherit at least one fourth and possibly one half (as the son of the firstborn). If Er remained childless, then Judah’s estate would be divided into three, with the eldest, most probably Onan, inheriting two thirds. Onan opts to preserve his financial advantage and interrupts coitus with Tamar, spilling his semen on the ground. For this, God punishes Onan with death, as God had previously punished Er for doing something wicked.

Although the readers know that God has killed two of Judah’s sons, Judah does not. He suspects that Tamar is a “lethal woman,” a woman whose sexual partners are all doomed to die. So, Judah is afraid to give Tamar to his youngest son, Shelah. As a result, Judah wrongs Tamar. According to Near Eastern custom, known from Middle Assyrian laws, if a man has no son over ten years old, he could perform the Marriage between a widow whose husband died childless (the yevamah) and the brother of the deceased (the yavam or levir).Levirate marriage (yibbum) obligation himself; if he does not, the woman is declared a “widow,” free to marry again. Judah, who is perhaps afraid of Tamar’s lethal character, could have set her free. But he does not—he sends her to live as “a widow” in her father’s house. Unlike other widows, she cannot remarry and must stay chaste on pain of death. She is in limbo.

Ostensibly, Tamar is only waiting for Shelah to grow up and mate with her. But after time passes, she realizes that Judah is not going to effect that union. She therefore devises a plan to secure her own future by tricking her father-in-law into having sex with her. She is not planning incest. A father-in-law may not sleep with his daughter-in-law (Lev 18:15), just as a brother-in-law may not sleep with his sister-in-law (Lev 18:16), but in-law incest rules are suspended for the purpose of the levirate. The levir is, after all, only a surrogate for the dead husband.

Tamar’s Plan

Tamar’s plan is simple: she covers herself with a veil so that Judah won’t recognize her, and then she sits in the roadway at the “entrance to Enaim” (Hebrew petah enayim; literally, “eye-opener”). She has chosen her spot well. Judah will pass as he comes back happy and horny (and maybe tipsy) from a sheep-shearing festival. The veil is not the mark of a prostitute; rather, it simply will prevent Judah from seeing Tamar’s face, and women sitting by the roadway are apparently fair game. So, Judah propositions her, offering to give her a kid for her services and giving her his seal and staff (the ancient equivalent of a credit card) in pledge.

Judah, a man of honor, tries to pay. His friend Hirah goes looking for her, asking around for the kedeshah in the road (Gen 38:21.). The NRSV translates this as “temple prostitute,” but a kedeshah was not a sacred prostitute; she was a public woman, who might be found along the roadway (as virgins and married women should not be). She could engage in sex, but might also be sought out for lactation, midwifery, and other female concerns. By looking for a kedeshah, Hirah can look for a public woman without revealing Judah’s private life. The woman, of course, is nowhere to be found. Judah, mindful of his public image, calls off the search rather than became a laughingstock.

But there is a greater threat to his honor. Rumor relates that Tamar is pregnant and has obviously been faithless to her obligation to Judah to remain chaste. Judah, as the head of the family, acts swiftly to restore his honor, commanding that she be burnt to death. But Tamar has anticipated this danger. She sends his identifying pledge to him, urging him to recognize that its owner is the father. Realizing what has happened, Judah publicly announces Tamar’s innocence. His cryptic phrase, zadekah mimmeni, is often translated “she is more in the right than I” (Gen 38:26), a recognition not only of her innocence, but also of his wrongdoing in not freeing her or performing the levirate. Another possible translation is “she is innocent—it [the child] is from me.” Judah has now performed the levirate (despite himself) and never cohabits with Tamar again. Once she is pregnant, future sex with a late son’s wife would be incestuous.

Assertation of Power

Tamar’s place in the family and Judah’s posterity are secured. She gives birth to twins, Perez and Zerah (Gen 38:29–30; 1 Chr 2:4), thus restoring two sons to Judah, who has lost two. Their birth is reminiscent of the birth of Rebekah’s twin sons, at which Jacob came out holding Esau’s heel (Gen 25:24–26). Perez does him one better. The midwife marks Zerah’s hand with a scarlet cord when it emerges from the womb first, but Perez (whose name means “barrier-breach”) edges his way through. From his line would come David.

Tamar was assertive of her rights and subversive of convention. She was also deeply loyal to Judah’s family. These qualities also show up in Ruth, who appears later in the lineage of Perez and preserves Boaz’s part of that line. The blessing at Ruth’s wedding underscores the similarity in its hope that Boaz’s house “be like the house of Perez, whom Tamar bore to Judah” (Ruth 4:12). Tamar’s (and Ruth’s) traits of assertiveness in action, willingness to be unconventional, and deep loyalty to family are the very qualities that distinguish their descendant, King David.

Adelman, Rachel, “Ethical Epiphany in the Story of Judah and Tamar.” In Recognition and Modes of Knowledge: Anagnorisis from Antiquity to Contemporary Theory, edited by Teresa Russo, 51-76. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013.

Bos, Johanna. “Out of the Shadows: Genesis 38; Judges 4:17–22; Ruth 3.” Semeia 42 (1988): 37–67.

Friedman, Mordechai. “Tamar, a Symbol of Life: The ‘Killer Wife’ Superstition in the Bible and Jewish Tradition.” American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literature Review 15 (1990): 23–61.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. “Royal Origins: Tamar.” In Reading the Women of the Bible, 264-277. New York: Schocken Books, 2002.

Kugel, James. “Judah and the Trial of Tamar.” In The Ladder of Jacob, 169-185. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Niditch, Susan. “The Wronged Woman Righted: An Analysis of Genesis 38.” Harvard Theological Review 72 (1979): 143–149.

Westenholz, Joan Goodnick “Tamar, Qedesa, Qadistu, and Sacred Prostitution in Mesopotamia.” Harvard Theological Review 82 (1989): 245–265.