Bathsheba: Bible

The biblical narratives featuring Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11-12; 1 Kings 1-2) entail adultery and bloodshed, prophetic rebuke and tragic consequences, and the breaking and making of the throne. From his roof, King David (reigns c. 1005–965 BCE) sees beautiful Bathsheba, wife of Uriah, bathing, and he lies with her. Uriah is summoned from the front to cover for the resulting pregnancy, but when he refuses to go home, the king has him slain in battle. David then marries the widowed Bathsheba, who bears a son. In response to the adultery and murder, the prophet curses David’s House, the first consequence being the death of the infant conceived in adultery. Yet Bathsheba ensures that their second son, Solomon (reigns c. 968–928 BCE), becomes successor to the throne.

Bathsheba’s First Appearance

In the first scene of the Bathsheba narrative, David, who remains in the palace while his troops are deployed in war, spies a woman bathing from his rooftop after a late afternoon siesta. Set against the background of the siege of the Ammonite town, Rabbah (1 Sam 11:1; 12:26–31), the battle occasions Bathsheba’s husband Uriah’s absence from home and the adultery, his summons from the front to cover for the resultant pregnancy, and his eventual death. The contrast between David and Uriah implies a searing critique of the king’s power, when the corrupt king takes his loyal soldier’s wife to bed. Bathsheba is first introduced by name when the king sends messengers to enquire after the woman, who report: “Is this not Bathsheba, daughter of Eliam, wife of Uriah the Hittite?” (11:3). Her father and husband are both members of David’s elite vanguard (2 Sam 23:34, 39); her grandfather, Ahitophel, father of Eliam, is one of the king’s wisest counselors (who later betrays David in allying with Absalom, chs. 15–16). Despite her status as a married woman and the illustrious men with whom she is affiliated, David summons her for his pleasure (2 Sam 11:4–5):

So David sent messengers, and took her, and she came to him, and he lay with her.

(she was purifying herself of her uncleanness). And she returned to her house.

The woman conceived; and she sent [word] to David, and said: “I am pregnant.”

Bathsheba’s role in these few terse lines reveals very little of her feeling or character. She plays an almost entirely passive role in this chapter and utters only three words (two in Hebrew). The parenthetical aside about her purifying herself may refer back to the roof bath as a ritual cleansing at the end of her period, which would affirm David’s paternity. Alternatively, the purification takes place after they lie together and alludes the ritual of cleansing following sexual relations (Lev 15:15-17). Yet Bathsheba cannot wash herself of the consequences, and a month or two later she is compelled to send word that she is pregnant. She alone carries the results of the tryst in her body.

Did Bathsheba lie with the king willingly? Some readers suggest that she deliberately positions herself on the roof, bathing naked within David’s purview so that he would take her and make her one of his wives, and thus she would perhaps bear the future king. It seems, however, that he wants her only for that one time; she alone risks the death penalty for adultery, given her husband’s absence, the resulting pregnancy, and the king’s absolute power. Others suggest that she is raped, since she has no wherewithal to resists the king’s summons, though the language does not imply force. As the story unravels, the narrative seems to exonerate Bathsheba of any guilt and is exclusively concerned with the king’s degeneracy. While David has no intention of continuing the liaison, the pregnancy embroils him.

The Consequences of the Adultery

To David’s credit, he does not deny his role in the conception. In order to cover for his paternity and free Bathsheba from suspicion of adultery, he summons Uriah from the front to sleep with his wife. But the soldier repeatedly refuses to go to his house, swearing loyalty to the troops (2 Sam 11:11). David then sends him back to the front, with a letter to the general, Joab, to set Uriah up to be slain in battle. After hearing of Uriah’s death, Bathsheba laments over him (v. 26). David waits the requisite mourning period and then summons her to become his wife. She bears him a son, the progeny of their illicit union, yet “the thing was evil in the eyes of the LORD” (v. 27).

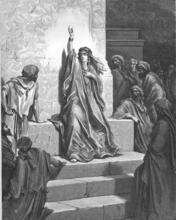

Nathan, the prophet, is then sent to the king to rebuke him and awaken his conscience by way of a parable. Though David confesses and repents, he suffers the consequences of his sins: the sword will never leave his house and another man will possess his wives in public (2 Sam 12:11–12; see 16:21–22). Post-haste, the doom-toll plays itself out, first with the illness and death of the infant son (12:15–20); then the incestuous rape of David’s daughter, Tamar by Amnon, his firstborn son (13:1–22); and finally the murder of Amnon, by the next in line to the throne, Absalom (13:23–37), who stages an insurrection against his father, instigates a civil war, and is slain in battle. Indeed, justice is meted out tragically, the sons mirroring and amplifying the sins of the father.

While David’s elaborate mourning for the infant son is drawn out over several verses (2 Sam 12:15–23), we only hear of Bathsheba’s response when he turns to console her (v. 24). This is the one time she is identified as “his wife”; throughout the rest of the story, she is referred to as “wife of Uriah” (2 Sam 11:3, 22, 26; 12:9, 10, 15; cf. Matt 1:6). In these early scenes, Bathsheba is almost without agency—merely a married woman and the object of the king’s lust.

The Birth of Solomon and the Making of a King

Yet Bathsheba plays a more active role in guaranteeing that her second son becomes successor to the throne. She intimates his royal future by naming him “Solomon [Shlomoh]” (2 Sam 12:24), which suggests well-being or wholeness [shlm]. We see here an early alliance between Bathsheba and Nathan, the prophet, who gives the child a second name, “Jedidiyah [Yedidyah],” meaning “friend” or “beloved of God.” Indeed, this son will become heir to the crown and build the temple in Jerusalem (see 2 Sam 7:12–14).

In the opening chapters of the book of Kings, Bathsheba plays an active role to ensure that her son is designated heir to the throne. David, feeble with old age, does not know that his son, Adonijah, the presumptive heir, has set himself up as king. Nor does he “know” (in the biblical sense) the beautiful young woman, Abishag, who lies with him to keep him warm. Far from his former self, the king has declined into sexual and political impotence. Nathan then colludes with Bathsheba to “remind” David of his oath to her to make Solomon, their son, king (though no oath is recorded earlier in the biblical account). She follows the prophet’s script (1 Kgs 1:11–14) but adds God’s name to the oath: “My lord, you yourself swore by the LORD your God to your handmaid, saying: ‘Indeed Solomon your son shall reign as king after me, and he shall sit on my throne’” (v. 17). She then emphasizes the danger she and her son are in, given their exclusion from Adonijah’s alliance (v. 20). When Nathan corroborates her words, David, in turn, swears in the name of God and Israel to make Solomon king.

In yet another invocation of an oath, Bathsheba plays a pivotal role—either wittingly or unwittingly—in eliminating the rival brother, Adonijah son of Haggith. Again she plays the messenger to her son, the king, in requesting Abishag as wife on behalf of Adonijah (1 Kgs 2:13–25). Seeing the request as a bid for the throne, Solomon utters an oath to have his brother executed. As a consequence of her role in the succession narrative, her name “Bathsheba,” which might mean “daughter of abundance” or “daughter of seven,” takes on a whole new meaning as “woman of oath [bat-shvu‘ah].” Given her contrasting roles—the earlier passive and opaque, the latter influential and perhaps conniving—we can read her story as either two very different characters or as a narrative of psychological transformation.

Adelman, Rachel. The Female Ruse: Women’s Deception and Divine Sanction in the Hebrew Bible. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2017.

Berlin, Adele. Poetics and Interpretation of Biblical Narrative. Sheffield: Almond Press, 1983; Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 1994.

Ehrlich, Carl, S., “Bathsheba the Kingmaker.” TheTorah.com (2020). Last Updated

January 6, 2021. https://thetorah.com/article/bathsheba-the-kingmaker.

Exum, Cheryl J., Fragmented Women: Feminist (Sub)versions of Biblical Narratives. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993.

Garsiel, Moshe. Biblical Names: A Literary Study of Midrashic Derivations and Puns. Translated by Phyllis Hackett. Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 1991.

Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Reading the Women of the Bible. New York: Schocken Books, 2002.

Koenig, Sara, M. Isn’t This Bathsheba?: A Study in Characterization. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2011.

Yee, Gale A. “’Fraught with Background’: Literary Ambiguity in II Samuel 11.” Interpretation 42 (1988): 240–53.