Spirituality in the United States

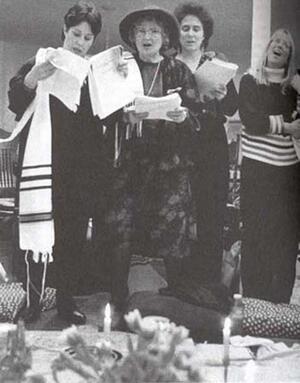

Feminist seders have provided an important context for developing women’s spirituality. In 1975, a group of Israeli and American women decided to create their own Passover seder based on their experiences as Jewish women. Now an annual event held in Manhattan, it has been attended by Esther Broner, Gloria Steinem, Letty Cottin Pogrebin, Bella Abzug, Grace Paley and several other "Seder Sisters" who have played important roles in the development of Jewish feminism. Shown here are Bella Abzug, Phyllis Chesler and Letty Cottin Pogrebin at the Women's Seder in 1991.

Photo: Joan Roth

Spirituality can be defined as life lived in the presence of God. It embraces not only traditional and formal modes of religious expression, but also more informal individual and communal efforts to remain mindful of the sacred in all aspects of experience. Historically, Jewish women’s spirituality developed within the confines of a patriarchal tradition. The proper focus of women’s spiritual home was considered to be the home, and within this sphere women elaborated their own customs and conventions. Over time feminists have developed rituals and created spaces that honor the unique experiences of women. Since the 1970s, feminist theologians have attempted to reimagine every aspect of Judaism, including the gender of God.

Introduction

Spirituality can be defined as life lived in the presence of God. It embraces not only traditional and formal modes of religious expression, but also more informal individual and communal efforts to remain mindful of the sacred in all aspects of experience.

Jewish women’s spirituality developed historically within the confines of a patriarchal tradition. The sages understood woman’s nature as more private than man’s—“the entire glory of the king’s daughter lies on the inside” (Ps. 45:14)—and thus the proper focus of her spiritual life was considered the home. Within this sphere, women elaborated their own customs and conventions that were passed on from mother to daughter. But even if these were distinct from or in tension with the larger male tradition, they remained constrained by its boundaries. Feminist spirituality, as it has developed since the late 1960s, represents a new phenomenon. It constitutes a self-conscious, critical attempt to transform Jewish tradition, for the sake of justice for women and in the name of perspectives and values said to be represented by women. It involves women claiming the power to participate fully in and actively shape Jewish religious life.

The Fight for Equal Access

The first feminist efforts at creating a self-conscious women’s spirituality revolved around claiming equal access to the (formerly male) public Jewish spaces of the synagogue and the house of study. Arguing that women should not be barred from those forms of prayer and learning that have formed the heart and soul of traditional Judaism, women in non-Orthodox denominations fought—successfully—for the rights to lead services, read from the Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah, be counted in a The quorum, traditionally of ten adult males over the age of thirteen, required for public synagogue service and several other religious ceremonies.minyan (quorum of ten (men) necessary for a full service), and enjoy admission to the rabbinate and cantorate. Orthodox women formed women’s Prayertefillah (prayer) groups, in which, in the absence of men, they could lead services, read from the Torah and haftarah (additional reading for the Sabbath), and recite all prayers not requiring a minyan. Despite opposition from some segments of the Orthodox world, these groups have proliferated and flourished.

Separate Spaces

Feminists have not confined themselves, however, to laying claim to forms of spiritual expression formerly reserved for men. They have also raised questions about the existence and content of a specifically female spirituality. Should it be the goal of feminism simply to adopt traditionally male forms of study and worship? Are there uniquely female spiritual experiences and perspectives? Do women have anything distinctive to contribute to Jewish spirituality—not because they are more interior or more innately pious than men (as the tradition has sometimes claimed), but because of their long history of separation, subordination, and marginalization? What would it mean for women to begin self-consciously to explore their spiritual lives as women?

These questions represent a strand of feminist exploration that sometimes informs the struggle for equal access but is also distinct from it. Such questions have most often been addressed in women-only contexts in which participants have considerable freedom to play with the boundaries of tradition. Since 1976, when Arlene Agus first wrote about Rosh Hodesh (the new moon) as a woman’s holiday, for example, women’s Rosh Hodesh groups have sprung up all over the United States. Serving as important vehicles of feminist organizing, Rosh Hodesh groups have used the association of women with the moon in A type of non-halakhic literary activitiy of the Rabbis for interpreting non-legal material according to special principles of interpretation (hermeneutical rules).midrash and folk tradition as a foundation for wide-ranging spiritual exploration and liturgical inventiveness. The brief Rosh Hodesh liturgy has provided feminists with a jumping-off point for developing new rituals and stories that attempt to link generations of Jewish women. Rosh Hodesh ceremonies appear in a number of collections, including Penina Adelman’s Miriam’s Well (1986), which draws on twenty years of feminist Rosh Hodesh organizing, and the newsletter Rosh Hodesh Exchange. Orthodox women’s prayer groups, which sometimes are organized around Rosh Hodesh, have also begun creating and circulating new liturgy that reflects women’s life experiences.

Feminist seders (A seven-day festival to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt (eight days outside Israel) beginning on the 15th day of the Hebrew month of Nissan. Also called the "Festival of Mazzot"; the "Festival of Spring"; Pesah.Passover liturgical meals) have provided another important context for developing women’s spirituality. Many college campuses and women’s groups around the country have established a tradition of a third Lit. "order." The regimen of rituals, songs and textual readings performed in a specific order on the first two nights (in Israel, on the first night) of Passover.seder that uses the structures and themes of the The "guide" to the Passover seder containing the Biblical and Talmudic texts read at the seder, as well as its traditional regimen of ritual performances.Haggadah (Passover liturgy) to reflect on the situation of women within Judaism. Moving from the freedom of the Jewish people to the hoped-for liberation of women, feminist seders provide opportunities for both celebrating women’s history and reflecting critically on the erasures of women’s experience from the Haggadah and other mainstream texts that make a third seder necessary. Such seders fall anywhere along a continuum, from those that remain fairly close to the traditional liturgy, integrating women’s history and experience into the established narrative of the liberation from Egypt, to those that shift the focus of the Haggadah from the liberation of the Israelites to the liberation of women.

Another kind of separate space is provided by Jewish feminist retreats, conferences, and spirituality collectives that seek to provide special and concentrated time for exploring issues of women’s spirituality. In 1981, a group of Jewish feminists founded B’not Esh (daughters of fire), a collective that began with the goal of reconfiguring Judaism from a feminist perspective. Meeting annually for four days over Memorial Day weekend, B’not Esh has generated a number of spin-offs, including Achiyot Or (sisters of light) and Bat Kol (daughter of the voice/the divine voice). While these groups differ in tone and emphasis, they all provide opportunities for study, extensive ritual/liturgical experimentation, and exploration of the relationship among feminism, spirituality, and issues of everyday life. Taking up topics from sexuality, to politics, to cost sharing, to the meaning of women’s Torah, they all attempt to imagine and create a Judaism that thoroughly integrates women’s experiences. Such groups—and other conferences and retreats—are necessarily limited in the number of participants who can be directly involved, but they have generated ideas and resources that have spilled over into a larger Jewish feminist community.

Rituals and Ceremonies

Institution: Eleanor Leff Jewish Women’s Resource Center (JWRC) of the National Council of Jewish Women, New York Section

While most Jewish feminist spiritual experimentation has been communal in nature, a fair amount of the ritual generated by feminist groups has revolved around the individual life cycle. The absence of a traditional ceremony for celebrating the birth of a daughter, the absence of blessings for the central moments in women’s biological lives, the desire to find Jewish ways to affirm the female body and to value relationships between women have all served as important stimuli to feminist ritual inventiveness.

Birth ceremonies for girls were the earliest feminist ritual innovation, and the one most widely accepted and adopted. In the early 1970s, many couples created rituals around the births of their daughters. Daniel and Myra Leifer, for example, wrote ceremonies for the moment of birth, naming, and pidyon habat (redemption of the firstborn daughter), while Sharon and Michael Strassfeld immersed their daughter in the Ritual bathmikveh (ritual bath) to welcome her into the covenant. Since then, others have searched hard for a symbolic act or series of acts that could match the power and significance of Circumcisionberit milah (the covenant of circumcision). Feminists have tried or suggested a variety of rituals, from washing a girl’s feet as a sign of welcome, to breaking her hymen, to offering her a ritual object (for example, a prayer shawl or Lit. "sanctification." Prayer recited over a cup of wine at the onset of the Sabbath or Festival.Kiddush cup) that expresses her parents’ hopes for her future participation in the Jewish community.

Once feminists discovered that it was possible to create effective new ceremonies, new rituals multiplied, each seeking to create some Jewish marker for a central event or crisis in women’s lives. Jewish feminists have developed rituals for, among other things, menarche, childbirth, weaning, miscarriage, rape, and hysterectomy. A number of women have held “croning” ceremonies in which, on reaching sixty, they celebrate wisdom and the entry into a new phase of life. Other rituals have sought to sanctify significant non-biological turning points, such as rabbinic ordination, moving across country, becoming a vegetarian, or coming out as a lesbian. For a long time, such new rituals circulated only privately, so that women looking for new ceremonies were generally forced to invent them from scratch. Collections by Elizabeth Resnick Levine, Ellen Umansky and Dianne Ashton, and Debra Orenstein now gather at least some of these resources together, making them available to a wide audience.

The creation of new life-cycle rituals poses special challenges to Jewish lesbians, who are doubly excluded from the Jewish ceremonial cycle. According to Rebecca Alpert, who has been a leader in this area, lesbians must both reconstruct those rituals they hold in common with all other Jews and create new rituals that speak to their difference. While commitment ceremonies have been the most visible area of lesbian ritual creativity, lesbians must also transform mourning rituals that do not recognize a lesbian partner as a mourner, find ways to celebrate the birth or adoption of a child in the context of a lesbian relationship, and make connections between the cycle of the year and lesbian experience of liberation. The fact that some feminist seders, for example, incorporate references to Jewish lesbians or highlight the lesbian experiences indicates that Jewish lesbians have been active and involved in leadership roles in all areas of feminist spiritual experimentation, even as they have had to remain alert to the heterosexual bias present in some feminist ceremonies.

Feminist Theology

Apart from the absence of Jewish markers for significant events in women’s lives, discomfort with traditional male God-language was the most important early catalyst for the creation of feminist liturgy. Convinced that the traditional prayer book is idolatrous because it identifies the image of God with maleness, feminists tried to reimagine the sacred by speaking of God as female. The fullest early experiment with new language was Maggie Wenig and Naomi Janowitz’s Siddur Nashim (1976), a Sabbath prayer book in English that referred to God throughout using female pronouns and imagery.

Since the 1970s, feminist experiments with imagery have broadened and deepened. Changes in the gender of God have evolved into more fundamental changes in conceptions of God, and changes in English translations of prayers have begun to be combined with changes in the original Hebrew. Feminists have focused on the immanence of God within the world and within women; they have called on God using a myriad of metaphors and have imagined her as moving and changing. Liturgists such as Lynn Gottlieb and Penina Adelman have drawn on female imagery from many traditions; used traditional Hebrew images for the divine, like Shekhinah, the feminine aspect of God in Jewish mysticism; and also created new names, like rahamema, compassionate giver of life. Feminist concerns have influenced a number of community and denominational prayerbooks: the Sudbury siddur V’taher Libenu, which alternates male and female God-language in its English translations; P’nai Or’s Or Chadash, which provides all Hebrew blessings in the masculine and feminine; and the Reconstructionist siddur Kol Haneshamah, which offers many images for God and includes numerous feminist offerings among its readings. These two lines of experimentation—with new images and new Hebrew—come together most fully in the work of Marcia Falk, whose The Book of Blessings (1996) entirely reworks the daily, Sabbath, and Rosh Hodesh liturgies from a feminist perspective.

While new forms of ritual, prayer, and God-language in many ways form the heart of feminist spiritual exploration, feminist spirituality has by no means been confined to these media. Midrash, for example, has been another important mode of feminist expression. Drawing on traditional techniques for explicating and expanding biblical texts and for resolving contradictions and filling in silences, feminists have created a host of new midrashim, focusing largely, but not entirely, on the female figures in the Bible. Where was Sarah when Abraham took the child born of her old age to offer him as a sacrifice on top of Mount Moriah? Why did Lot’s wife look back as the family fled Sodom? How did Miriam feel when she was punished with leprosy for challenging Moses’s authority? In classes, workshops, and women’s groups, feminists have been asking new questions of traditional texts and expanding on biblical narratives in ways that connect with their own experiences. Much of the midrash written in response to new questions remains in drawers or circulates privately, but the San Diego Woman’s Institute for Continuing Jewish Education has brought at least some of it together in its anthology Taking the Fruit.

Jewish feminist theology is a more theoretical form of spiritual expression that grows out of and attempts to reflect on the changes taking place in all these areas. What views of self, God, and world underlie feminist experiments with midrash or liturgy, and how might feminist worldviews express themselves in transformed liturgy and ritual? Where do feminist understandings of key Jewish categories converge with or diverge from traditional rabbinic conceptions? How do the new texts women are creating shape or transform the meaning of Torah? Is a feminist halakhah (Jewish law) possible, and what would it be like? What makes Jewish feminist ritual/God-language/midrash Jewish? Feminists such as Judith Plaskow, Rachel Adler, Ellen Umansky, Drorah Setel, and Laura Levitt have produced a range of theoretical work that tries to reconceptualize central aspects of Jewish life and thought from differing feminist perspectives. Plaskow has written the only book-length systematic feminist Jewish theology, Standing Again at Sinai.

Other avenues of feminist creativity have been as rich and varied as the talents of feminists themselves. Alicia Ostriker and E. M. Broner have developed powerful midrash and ritual through poetry and fiction. Fanchon Shur has used dance to try to convey the spiritual power of women. Ruth Wiesberg and others have celebrated women’s spiritual lives through painting and other visual arts. Many Jewish feminists see feminist activism itself as a significant mode of spiritual expression. Efforts to create a Judaism that fully incorporates the diversity of women’s experiences contribute to tikkun olam, the healing or repair of the world.

What other shapes feminist spirituality will take and which of its innovations will become part of the mainstream, are difficult to predict. As women take on new roles, as they engage with, challenge, and transform tradition, they create a new Jewish reality that itself becomes the foundation for further evolution.

Adelman, Penina V. Miriam’s Well: Rituals for Jewish Women Around the Year (1986).

Agus, Arlene. “This Month Is for You: Observing Rosh Hodesh as a Woman’s Holiday.” In Koltan, The Jewish Woman.

Falk, Marcia. The Book of Blessings (1996).

Haut, Rivka. “Women’s Prayer Groups and the Orthodox Synagogue.” In Daughters of the King: Women and the Synagogue, edited by Susan Grossman and Rivka Haut (1992).

Koltun, Elizabeth, ed. The Jewish Woman: New Perspectives (1976).

Levine, Elizabeth Resnick, ed. A Ceremonies Sampler: New Rites, Celebrations, and Observances of Jewish Women (1991).

Orenstein, Debra, ed. Lifecycles: Jewish Women on Life Passages and Personal Milestones (1994).

Plaskow, Judith. Standing Again at Sinai; Umansky, Ellen M., and Dianne Ashton, eds. Four Centuries of Jewish Women’s Spirituality: A Sourcebook (1992).

Wenig, Maggie, and Naomi Janowitz. Siddur Nashim (1976).

Zones, Jane Sprague, ed. Taking the Fruit: Modern Women’s Tales of the Bible (1981).