Sol Hachuel

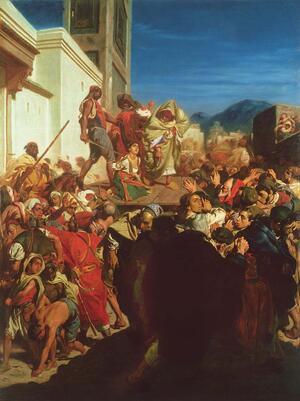

Execution of a Jewess in Tangiers, by Alfred Dehodencq, c. 1861, depicting the execution of Lalla Soulika (also known as Sol Hachuel) for refusing to convert to Islam. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Sol Hachuel, known also as Lalla Soulika or Sol ha-tsaddeqet, was a nineteenth-century martyr whose resting place is still an important pilgrimage destination for Moroccan Jews and Muslims alike in the twenty-first century. Sol Hachuel was a young Moroccan Jewish woman who refused to convert to Islam at the Sultan of Morocco’s request. She was put to death instead, only a teenager when she was killed. In the decades that followed her martyrdom, Sol Hachuel’s tomb was thought to have been endowed with powers of fertility and healing, solidifying her status as a saint.

A Captivating Beauty

Sol Hachuel descended from Sephardic Jews (Jews who hailed from Spain, or “Sepharad” in Hebrew) who had settled in northern Morocco after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. According to lore, Jews have resided in North Africa since the destruction of the first temple in the sixth century BCE. Historians can date Jewish life in the region to at least the Roman period. There was a great diversity of Jewish life in Morocco, including Jewish speakers of Tamazight (Berber), Judeo-Arabic, and Haketía, the Judeo-Spanish dialect spoken among northern Moroccan Jews. Jews lived in rural communities of the Atlas mountains as well as the major urban centers, such as Fez, or in Sol Hachuel’s case, Tangier. At its height, the Jewish population of Morocco was approximately 250,000. Most Jews left Morocco for Israel, France, or the Americas in the 1950s and 1960s due to a combination of political and social pressures.

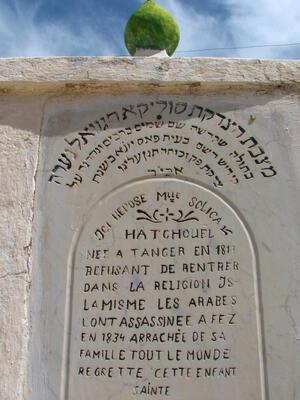

Sol Hachuel, better known as Lalla Soulika or Sol ha-tsaddeqet (“Sol the saint” in Hebrew; the term “saint” is often used in reference to such figures in Morocco, whereas “righteous” is more commonly used in other settings), was born in Tangier in 1817. She was beheaded in a public execution in Fez in 1834. Depending on which of the numerous versions of the story one consults, she was executed either for refusing to convert to Islam or for converting to Islam and then recanting. According to every version of the story, Soulika was very beautiful, so beautiful that Muslims as well as Jews wailed upon her death.

According to Sharon Vance, author of a comprehensive book about Soulika, the bare bones of the story are as follows: Soulika’s family was not wealthy enough to afford domestic servants, so Soulika and her mother, Simha, did all the housework. Simha was frequently harsh with Soulika, shouting at her and threatening bodily harm. On one particularly difficult day, Soulika ran for refuge at her neighbor’s house. The neighbor, Tahra, was a Muslim and informed Soulika that if she were to convert to Islam, she would be out of her mother’s reach and could not be harmed.

Conversion or Death

Here is where versions of the story differ. According to Muslim sources, Soulika converted and then recanted, thus committing apostasy, which earned a death sentence. According to Jewish sources, Soulika was given the choice to convert or die but never converted. In either event, after a short stay in prison in Tangier, Soulika was transferred to Fez, where the Sultan of Morocco would hear her case.

After six days of overland travel, Soulika arrived at the Sultan’s palace, where she was admitted to the women’s quarters, bathed, and rested before appearing before the Sultan. The Sultan, like everyone else, was struck by her beauty and encouraged her to convert to Islam, promising marriage to a wealthy Muslim. Soulika refused. According to some versions of the story, a delegation of rabbis from Fez encouraged her to convert and live as a crypto-Jew; in others, the rabbis encouraged her to remain steadfast and not convert.

Growing Veneration

On the day of Soulika’s death, the executioner wounded her slightly and gave her one more chance to convert; she refused and was beheaded. The Jews of Fez buried her body in the Jewish cemetery, in a well-built tomb near the tombs of notable sages. Since then, Muslims as well as Jews have visited Soulika’s tomb (it is common for Moroccan Muslims to venerate Jewish holy figures as well as Muslims to receive their supernatural beneficence), which, according to folklorist Issachar Ben Ami, is associated with fertility and healing sick children. In his book about Moroccan Jewish saints and their veneration, Ben Ami details several anecdotes from those whose children were healed or saved by Soulika. One memorable story concerns an underweight baby who was given a poor prognosis by the doctor. In desperation, the father took the baby in a covered basket and put him in the sizeable niche of the tomb used for candles. When he removed the baby, he was healed.

Vance’s book details the numerous versions of Soulika’s story, by Europeans, North African Muslims, and North African Jews. Notably, in 1902 the story was taken up and serialized in La Epoka, a Ladino-language newspaper in far-away Salonica (today’s Thessaloniki, Greece). It was also related in 1929 as a serialized novel in l’Avenir Illustré, a Casablanca newspaper.

Lalla Soulika’s tomb remains a site of veneration to this day, a popular stop on Jewish heritage tours in Morocco. The tomb is well marked, with a large niche for votive candles and a portrait of Soulika on one side, as well as her story in multiple languages. An Israeli band of North African and Middle Eastern heritage, “Sfatayim,” recorded a song about the dramatic events surrounding Soulika’s martyrdom.

Ben Ami, Issachar. Saint Veneration Among the Jews in Morocco. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

Vance, Sharon. The Martyrdom of a Moroccan Jewish Saint. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2011.