Maria Anna Schirmann

Maria Anna Schirmann was a Viennese physicist specializing in high vacuum physics, with several patents on devices she developed to conduct her experiments. She was among the generation of European female scholars who seized academic opportunities available in the twentieth century’s first decades. She earned a doctorate from the University of Vienna and in 1922 obtained a prestigious position at its Institute of Physics. Yet, she also faced discrimination as a woman and as a Jew that kept her from securing a permanent position on the university faculty. Like many of her contemporaries, the double prejudice made it harder to obtain an American university position that might have allowed her to immigrate outside restrictive quotas and escape Vienna. In 1941, she was deported to Poland, where she died.

Introduction

Trapped in a ghetto in Poland in 1941, Viennese physicist Marie Anna Schirmann received some unexpected correspondence. Franz Linke, editor of the eighth volume of the Handbook of Geophysics, wrote Schirmann to demand that she complete the article she had been working on before the Germans crammed her and a thousand other Jews into a train and sent them to Modliborzyce, near Lublin. Schirmann responded that she could not finish the work under the unbearable conditions in which she was forced to live—in an unheated wooden barrack without adequate lighting or food, and subject to repeated violent attacks. Linke, a University of Frankfurt professor of meteorology, was not dissuaded. He threatened the 48-year-old: If she did not send him the article within the next week, Linke would have the barracks searched and her manuscript and proof sheet confiscated.

Linke’s demand was the latest, but not even the last, blow Schirmann suffered from her fellow academics in what had been a promising career. Although Schirmann was a distinguished physicist in her own right—a specialist in high vacuum physics who obtained patents on several devices she developed to conduct her experiments—she also represents a generation of European female scholars who seized academic opportunities available for the first time in the early decades of the twentieth century, and yet still had to fight discrimination as women and as Jews. Ultimately, too many of their careers and lives were cut short, and, with a few exceptions such as Hannah Arendt and Lise Meitner, they have been forgotten. Like many of her contemporaries, the double prejudice made it more difficult for Schirmann to find an academic position that would enable her to escape Vienna when the Germans occupied it in 1938.

Early Life and Education

Schirmann was born on February 19, 1893, into what she described as an “old scholarly and artistic family” in Vienna that was assimilated. Her father, Moritz, was a music professor at Vienna Conservatory and her mother worked at St. Anna Children’s Hospital. Schirmann attended a girls’ high school in Vienna. Beginning in 1914, she studied physics and mathematics at the University of Vienna. She completed a PhD dissertation with distinction in 1918, which the renowned journal, Annals of Physics, published.

Once women were permitted to study at Austrian universities beginning in 1897, many entered the academic world, including in the natural sciences. At the University of Vienna, Schirmann’s was among 1,100 dissertations submitted by women in physics, chemistry, and zoology during the twentieth century’s first decades. Women accounted for 35 percent of the university’s physics students by the 1930s.

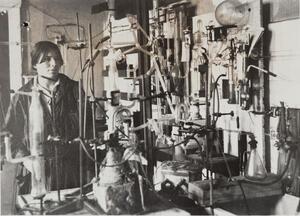

Schirmann was unusual, however, in obtaining in 1922 an assistantship in the University of Vienna’s Institute of Physics, a coveted research and teaching position for which women required special permission that was rarely granted. Before then, she had conducted practical and theoretical work on electron tubes and celestial polarization, receiving an award to study in Sweden under the head of the Nobel Committee for Physics. Returning to Vienna, Schirmann continued her research in applied physics at the Institute of Physics and obtained two additional patents.

The next step would have been to receive habilitation, an academic qualification after a doctorate that allowed for further teaching and research. Schirmann needed habilitation to remain on the University of Vienna faculty, which she could receive either by producing a second doctoral dissertation or by presenting a portfolio of advanced publications. The University of Vienna at that point had awarded habilitation to only one woman. In all Central European universities, only three female physicists received habilitation prior to World War II.

In 1928, the university extended Schirmann’s position for two years because she was needed as a teacher, but with the understanding that she would not seek habilitation. Schirmann applied anyway in May 1930, submitting a portfolio that included nine published articles and several patents. Although university regulations allowed such a “cumulative” habilitation, the faculty committee concluded the connection among her various works was not clear enough. The committee also relied on a highly critical expert opinion of Schirmann’s work that was later found to be without merit. Given the degree of discretion involved, Schirmann likely ran afoul of the university’s network of antisemites whose mission was to thwart the careers of Jews and leftists.

Denied habilitation, Schirmann had to leave the university. She started her own laboratory and worked as a private teacher. She soon obtained another patent for a cooling process for machines and published a book on methods and instruments of electrical medicine. She also became a contributor, along with 40 other scientists, to the Handbook of Geophysics that geophysicist Beno Gutenberg initiated in 1930. Gutenberg, who had Jewish ancestry, soon left Germany for the California Institute of Technology and in 1937 lost his rights to the handbook. Franz Linke, along with another meteorologist, took over the series, with Linke responsible for the volume, Physics of Atmosphere, that was to include Schirmann’s article on radiation problems in the sun and the sky and theories of the scattering of light.

"I beg you not to forget my condition"

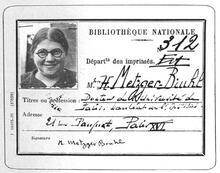

When Germany took control of Austria in March 1938, Schirmann, as a Jew, could no longer work in her lab, and she tried frantically to immigrate to the United States. Her lack of habilitation came back to haunt her.

Schirmann began her quest with the Emergency Committee in Aid of Displaced Foreign Scholars, a New York group that helped professors find American university positions so they could receive non-quota visas and thus immigrate outside of the restrictive quotas in place at the time. Quotas for German-Austrian immigrants were filled or close to filled in 1938, 1939, and 1940. The Emergency Committee was not convinced that Schirmann’s laboratory research qualified her as a professor, a requirement the State Department imposed for granting non-quota visas. Her lack of habilitation had prevented her from obtaining a faculty teaching position. Schirmann wanted Betty Drury of the Emergency Committee to know that she was not “a simple laboratory assistant,” which she clearly was not. Schirmann concluded her letter with a plea: “I hope you will succeed in helping a woman scholar who without guilt has soon to leave home, property, position and all her relatives and friends.”

Schirmann simultaneously registered for a quota number with the Vienna consul, but she needed affidavits of support. She turned to Cecilia Rasovsky of the National Refugee Service, an umbrella organization for several American refugee advocacy groups, who replied with what Schirmann considered a “promising letter.” Schirmann expressed her gratitude: “For in this place, every day, every hour bring us such affliction and grief as any hope gives us consolation.” With no relatives in neutral countries, Schirmann asked Rasovsky to contact several “interested and wealthy friends” who might provide affidavits: the wife and son of a deceased colleague; two former Institute of Physics colleagues, one at Vassar, the other whose address she didn’t know; her former University of Vienna professor then at Notre Dame; and a former professor from Berlin at the Seismological laboratory in Pasadena, California.

When American universities failed to express interest in Schirmann, the Emergency Committee tried another avenue: an appointment in the University of Philippines’ College of Engineering. In the meantime, Schirmann had received an offer of a temporary position in a University of Oxford meteorology lab. The International Federation of University Women, of which Schirmann had been a fellow, arranged the Oxford job, but it was conditioned on her having a United States position waiting for her in one or two years. Schirmann hoped the Emergency Committee’s Drury could arrange an American position so she could take the Oxford job and leave Vienna immediately.

As she was trying to get a university appointment, Schirmann also wrote repeatedly to Rasovsky for help in obtaining affidavits from Schirmann’s American acquaintances but received no reply. At the end of 1939, she grew increasingly concerned that her many registered letters had not been answered and that she had lost the possibility of going to England, due to the outbreak of war three months earlier. She was still willing to go to the Philippines, or even temporarily to Sweden. “I beg you not to forget my condition in this place, I am not able to describe,” Schirmann wrote Rasovsky. “But you are sure to know that I am obliged to leave this country and it is impossible for me to continue my scientific work in this place.”

In July 1940, Schirmann learned that the efforts to get her a University of Philippines appointment had failed. Two months later, she wrote to the International Federation of University Women, the organization that had found her a temporary position in England, in what was clearly a last-ditch appeal. “As a passionate defender of the feminist movement I am thoroughly convinced only a femal [sic] academic organization (Committee) will be in a position to help me in finding a new scientific activity in U.S.A.,” Schirmann wrote. “If I am able to obtain any University (College) position in U.S.A. I [as I am sure you know] can come to U.S.A. immediately, without any waiting till my turn on the immigration quota has come.” At the end of her letter, she wrote: “By reason of various circumstances I am not able to describe my condition here and all the mental suffering to be separated from my scientific work. Remain only the hope to find good colleagues in U.S.A., who are ready to help me for the sake of culture and science.”

"She is to perish there"

Six months later, on March 5, 1941, Schirmann, along with a thousand other Jews, was ordered to report to a school building at 35 Castellezgasse in Vienna and was then taken to the Aspang train station. She was prisoner 107. The group was deported to Modliborzyce, Poland, where they were placed in the town’s ghetto.

The Emergency Committee learned of Schirmann’s deportation a month later from Helmut Landsberg of Penn State’s Geophysical Laboratory, whom Schirmann had asked for help finding employment. Landsberg in turn had been informed by Linke, who had worked with Landsberg at the University of Frankfurt until Landsberg left in 1934. Landsberg explained to the Emergency Committee’s Drury that he wanted to “find out exactly what [Schirmann’s] status is and whether your Committee sees any possibility of helping her.” Drury responded: “I am afraid we are helpless here to do anything for her.” Drury noted that in the three and a half years that the Committee “had her papers on file we have had only one opportunity to suggest her as a candidate,” the position in the Philippines.

Drury received further news of Schirmann in December 1941. A friend of Schirmann’s, a former librarian at the University of Vienna who was in Sweden, wrote Drury that she had heard from Schirmann in Modliborzyce. She “is living there in a very hard situation,” K.A. Kolishcer wrote. “Having no means she was forced to sell her dress and—as I am informed by her—also her winter-dress is pawned.” (Ghetto residents survived by selling their meager last possessions, as Schirmann apparently had done.) Kolischer wanted Drury to send Schirmann money and food; “otherwise I could not hope this most learned and unhappy lady could life [sic] any longer—I think rather she is to perish there.”

Drury had an assistant telephone the American Red Cross. The employee with whom the assistant spoke promised to try to get in touch with Schirmann through the International Red Cross’ contact with the German Red Cross. “They held out little hope, however, that anything could be done to relieve her tragic situation.”

Franz Linke, editor of the Handbook of Geophysics, also knew about Schirmann’s tragic situation, but he was interested solely in her scientific work. Upon learning she had been deported, he sent an assistant, accompanied by an SS official, to claim her incomplete manuscript. Linke tried to finish it himself but could not. He needed Schirmann’s input. When Schirmann responded that it was impossible for her to do scientific work under the conditions in the ghetto, Linke took an unusual and risky step: he wrote the German head of the Lublin district to request that Schirmann be moved to a larger town— “preferably her home-town Vienna”—so she could finish the work.

Neither the head of the Lublin district nor the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda thought much of Linke’s request. Not only did they turn it down, but they questioned Linke’s sympathies in bringing it up. Linke then began furiously to justify himself. When someone informed the National Socialist German Lecturers League of the University of Frankfurt that “a university-professor, with the excuse, that a text should be revised, thinks that he can request the re-entry of a Jew,” Linke sent a detailed report to the League in early May 1942. He explained that when he first learned in 1937 that Schirmann was Jewish, he had tried to remove her from the project but was told she was the only person who could write the article. Linke said he then got the handbook publisher to obtain special permission to publish a Jew’s work. He later convinced other Reich ministries to agree that Schirmann’s article could be published anonymously. Linke wanted the Lecturers League to understand that publishing the article had become a point of German pride, because the handbook’s original editor, Gutenberg, was publishing his own version with British and American authors. “It is not only important that we publish our work faster than the Americans,” Linke wrote, “but also that it is better in terms of content and that it highlights German research.” Linke then reassured the Lecturers League that he had been known in Frankfurt for 30 years as an antisemite and had never interreacted socially with “the well-known wealthy Jewish families.”

Two days after sending the report, Linke wrote again to say that he had received Schirmann’s corrections. “I am glad that I am now relieved of the need to run after the Jew for corrections and even to call other authorities for help,” he wrote on May 9, 1942, to the league. “I hope that this is the end of this unpleasant matter.”

By that time, Schirmann had been in Modliborzyce for fourteen months. She would not last much longer. It is not known whether she succumbed to malnutrition, disease, or the German police’s and SS’s regular attacks on ghetto residents. Or she may have survived another five months until the ghetto’s liquidation on October 8, 1942, when the old and sick were slaughtered on the spot and the rest sent to the Belzec extermination center.

Around that time, the eighth volume of the Handbook of Geophysics appeared with Schirmann’s 100-page article in it. As a last blow, the article did not bear her name.

Bischof, Brigitte. “Women in Physics in Vienna.” In The Global and the Local: The History of Science and the Cultural integration of Europe, edited by M. Kokowksi, Proceedings of the 2nd ICESHS, Krakow, Poland, September 6-9, 2006.

Korotin, Ilse, and Nastasia Stupnicki, eds. Biografien Bedeutender Osterreichischer Wissenschafterinnen, Die Neugier Trebit Mich, Fragen Zu Stellen’. Vien: Bohlau Verlag 2018.

Leff, Laurel. Well Worth Saving: American Universities’ Life and Death Decisions on Refugees from Nazi Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

Lemberg, Jason. “The Scientific Exploitation of Marie Anna Schirmann: A Study of Intersectional Discrimination in Academia during the Holocaust.” OIn New Microhistorical Approaches to an Integrated History of the Holocaust, edited by Frederic Bonnsoeur, Hannah Wilson and Christin Zuhlke. Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2023.

Special thanks to Jason Lemberg for calling my attention to his research on Franz Linke’s efforts to force Maria Anna Schirmann to complete her academic article while imprisoned in the Modliborzyce ghetto.