Rothschild Women

Mayer Amschel Rothschild founded the family banking business dynasty in the late 1700s in Frankfurt, Germany. His wife, Gutle Rothschild, was deeply religious, modest, frugal, and a devoted and admiring wife and mother who had to face the stifling accommodations of the Jewish ghetto to which the family was subjected. In the family’s early history, women were excluded from participating directly in business matters but would often lend their indirect advice. Hannah Rothschild (1783-1850), wife of Nathan Rothschild, took a far more active role in business matters and advising than the conventional Rothschild wife. All Rothschild wives placed great emphasis on the education of their children, adopting the age-old Jewish tradition of the value of erudition and study. As their fortune grew through the centuries, the Rothschild women focused on philanthropy, often focusing on giving back to their fellow Jews.

Founding of the Rothschild Banking Business

There is no definitive history of Jewish women, we are told by Naomi Shepherd: “In all the historical literature produced since the end of the eighteenth century, women are a footnote to the story of Jewish survival.”

This in a sense is true of the women of the Rothschild family, for they accepted their traditional position in the community without question or demur. There is no Rosa Luxemburg or Emma Goldman or Golda Meir or even Lily Montagu among them.

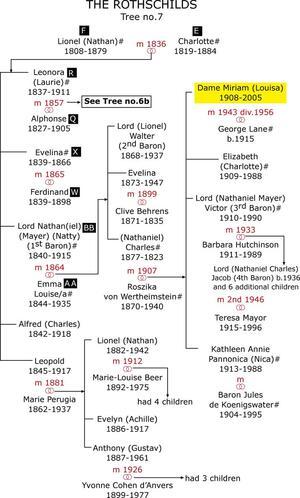

In 1770 the founder of the Rothschild banking business, Mayer Amschel (1744–1812), married a remarkable woman, Gutle Schnapper (1753–1849), whom he adored. Wed at the age of seventeen, she lived all her life in Frankfurt and, once installed in her home in the Judengasse (Jew Street), never left it. She bore her husband nineteen children, of whom ten survived to maturity. At the time of her marriage Jews were ranked as second-class citizens and suffered various disadvantages and much persecution. They were not allowed to leave Jew Street after dark or on Sundays or feast days; they were obliged to pay a heavy poll-tax and so-called “protection money”; they were not allowed to acquire land or to practice farming or handicrafts; they could not at that time trade in fruit, wine, silk or weapons; on every occasion they crossed a bridge they were obliged to pay a toll; they were barred from both taverns and the fashionable streets. They were frequently abused or stoned by street urchins. Furthermore, there were, periodically, serious pogroms and mass evictions. It is strange to reflect that five generations later my sister, Kathleen Annie Pannonica Rothschild (b.1913), daughter of Nathaniel Charles (1877–1923), earned herself the freedom of the skies—one of the first women in England to obtain a pilot’s license (“A” License). Her brother gave her a small aeroplane as a wedding present.

Gutle Rothschild

Gutle was a great character. There are few women, except for biblical heroines, or French Royal courtesans, or Queen Elizabeth I, whose comments have survived them or are quoted in contemporary publications. When Gutle was ninety-five, she fell ill and a doctor was called to her bedside. She had a poor opinion of his ministration and said so. The doctor expressed his regrets but unfortunately, he said, he was unable to make her younger. Her reply became famous: “I am not asking to be made younger,” she said. “All I want is to be made older.”

One of the appalling aspects of the ghetto was the overcrowding in Jew Street. Originally designed to squeeze in five hundred souls, it now accommodated three thousand. It is astonishing that in the congested space allocated to her family in the house of the Green Shield, Gutle could create a harmonious and industrious atmosphere. For instance, all the children had to share one tiny bedroom and the first Rothschild Banking house consisted of a back-room, three meters square, overlooking the tiny courtyard. The kitchen, in which Gutle cooked for her family of eleven, was a small passage about one and a half meters wide and four meters long, with space on the hearth for only a single pot; the furniture consisted of a bench and a small chest.

Gutle was deeply religious, modest, frugal, and a devoted and admiring wife and mother, who preserved her bridal wreath under a glass cover in her room—and coped admirably with the police who came to interrogate her about the family business.

My grandmother, Emma Louise (1844–1935), then aged only five, remembered Gutle who in very old age was visited from all over Europe by her sons and daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, while she remained the sole occupant of the house—unchanged—in Jew Street. The old lady gave Emma a brooch which, in due course, she handed to me and which I gave to my youngest daughter Charlotte (b. 1951), creating a sentimental family link of hands touching over a span of two hundred and forty years.

Women's Exclusion from the Business

In his Last Will and Testament (1812), Mayer Amschel bequeathed Gutle a life interest in seventy thousand guilders, but added the following paragraph in which he excluded the female members of his family from the business—even his daughter Henrietta (1791–1866), who had worked as his cashier.

I will and ordain that my daughters and sons-in-law and their heirs have no share in the trading business existing under the firm of Mayer Amschel Rothschild and Sons ... and [that it] belong to my sons exclusively. None of my daughters, sons-in-law and their heirs is therefore entitled to demand sight of business transactions ... I would never be able to forgive any of my children if, contrary to these my paternal wishes, it should be allowed to happen that my sons were upset in the peaceful possession and prosecution of their business interests. …

Twenty-four years later, Mayer Amschel’s ablest son, Nathan Mayer (1777–1836), left very different testamentary instructions for his sons.

My dear wife Hannah … is to co-operate with my sons on all important occasions and to have a vote upon all consultations. It is my express desire that they shall not embark in any transaction of importance without having previously demanded her motherly advice, and that all my children, sons and daughters, are to treat her with true love, kind affection and every possible respect, which she deserves in the highest degree, having shared with me joy and sorrow during so great a number of years, as a fond, true and affectionate wife.

Hannah Rothschild

His wife, Hannah Rothschild (1783–1850), daughter of Levi Barent Cohen (1740–1808), was described by Richard Davies as a woman of beauty, poise and charm. “Fond, true and affectionate she certainly was, but all these qualities were mixed with firmness and directness. … Age and responsibilities would not make her any less a woman of affairs.”

She undoubtedly discussed and advised Nathan on both business matters and politics. Lucien Wolf gives an example of Hannah’s determination and fearlessness. Moses Montefiore recalled how he and Nathan had a long discussion on the subject of the liberty of the Jews. Hannah joined in and said that if her husband did not consult the Lord Chancellor personally on the matter, she would go herself. Hannah thus assumed a far more active role in Nathan’s affairs than the conventional Jewish wife; for the three subsequent generations, until Roszika (1870–1940), the widow of Nathaniel Charles, became deeply interested in finance, Rothschild women took no part whatsoever in business matters.

The few letters of Hannah which have survived are distinctly unsentimental and impersonal in tone. This may have been commendable caution, since in those days letters sent by special messengers could easily fall into wrong hands. Her communications usually dealt with three or four distinct subjects. First, there was information about the children’s health and daily doings of the family and visits to friends; secondly, there was news and information and assessment of politics and military matters; thirdly, advice of investments and business and, finally, a few words about her own financial flutters. On one occasion Hannah mentions a purchase of three thousand ducats and sixty thousand rents. All her letters began “My dear Rothschild”—sometimes the “My” was dropped—and ended “Yours affectionately,” occasionally “As usual” or “And sincerely” was added. There were no endearments in the letters which are preserved but, occasionally, a half humorous, solicitous piece of advice is included about his health.

In one letter, written from Paris, she says: “I suppose in England this fall [in stocks and shares] will cause some alarm but there is no occasion as it appears more of a financial than a political one. You must look at it coolly, dear Rothschild.” Again: “In the Courier, the leading article speaks favourable of the Congress at Brussels. I think it reads very well and without doubt there should be something fresh of a different appearance if the affair between Belgium and Holland appears in a favourable way—it is most likely the funds will again improve if they should go to 83 1/2 I would like to buy 20,000.”

Hannah always counseled caution. “More I would not recommend, I think I would not sell, and wait till people are less agitated.”

Occasionally she was quite severe. Nathan, following in his father’s footsteps, had complained because Lionel (1808–1879) had failed to write his daily epistle. “My dear Rothschild your letters of today [July l, 1830] are rather grumpy. Lionel did not write on account of Saturday but I hope you are now quite satisfied that we do not neglect an opportunity. …Today the reports are of a much brighter cast and the funds also are assuming a better appearance. I think, dear Rothschild, a little ‘more patience and courage’ and the prices will again attain a good price.”

Nathan’s sons were all under thirty when he died and they were eager and relieved to be able to follow their mother in everything.

Hannah died in 1850—she collapsed while romping with her grandchildren in the garden at Gunnesbury. Davies remarked that she left her sons far more than a large fortune—“their principles among other things. …”

Rothschild Educational Values

All the Rothschild wives, Hannah included, took an infinite amount of trouble and worried perpetually over the education of their sons, nagging them relentlessly about the necessity for hard work and progress. They had inherited the age-old Jewish tradition of the value of erudition and study, but they were also boundlessly ambitious for their sons and believed that a splendid education, knowledge, and the mastery of languages were necessary for success in their particular profession. Their daughters, on the other hand, did not require instruction or guidance in this direction; they were taught agreeable accomplishments—to paint and draw, to play the piano and sing. Charlotte (1825–1899), daughter of Baron James (1792–1868), became a distinguished painter, exhibiting at the Salon from 1864 onwards. She earned a long paragraph in the Benezit Encyclopaedia of Artists. Likewise, Aline Caroline de Rothschild (1867–1909) was no mean painter.

The daughters were also encouraged to read voluminously, practice the social graces, and study religion and prayer seriously. Thus Clementine (1845–1865), daughter of Mayer Carl (1820–1886), a saintly girl who died tragically at the age of twenty, wrote a little book on the Fundamental Truths of Judaism. They were taught, by example, to be devoted mothers and wives, excellent housekeepers and hostesses. As females of the species, a subordinate position was accepted without question and considered as natural and as inevitable as sunrise. The Rothschild wives duly became magnificent examples of the triumph of nurture over nature. The mini-role they were assigned is well illustrated by the fact that in Count Corti’s two volumes—The Rise and Reign of the House of Rothschild—they were allotted one hundred forty-odd lines of his text, compared with thirty-four thousand for the male members of the family.

Emma Louise’s “Masculine Streak”

Occasionally there were one or two girls who insisted upon following their own interests; Emma Louise had a strong masculine streak which may have been encouraged by the absence of brothers. Her father, Mayer Carl, made no secret of his disappointment in seven daughters. She was an accomplished horsewoman, drove a four-in-hand, was proud of her life-saving certificates and amused at the memory of her skill at walking up and down stairs on stilts. What was more, she insisted on taking lessons in physics and mathematics. She learned the Morse code—subjects considered most unsuitable and unnecessary for a young woman. The series of tutors who came to her home in order to instruct her enquired politely what on earth could be the use of such learning and erudition in her future life. Emma was smilingly silent on how she parried their questions—and I did not dare ask her. All her life she enjoyed studying, listing every book she read in her diary. One of the last entries, when she was ninety-one, was Freud on Dreams.

Lord Rosebery, who greatly admired and liked her, once exclaimed: “Emma! You have the courage of a lion.” She certainly was cool and brave. Furthermore, she was one of those fortunate individuals who are not assailed by doubt. She knew what was right and what was wrong, all her long life uncompromisingly and forcefully following these deep convictions. Although such a serious character, Emma enjoyed society and entertaining friends and interesting visitors. She loved trees and little birds.

Mathilde’s Musical Talent

Mathilde (1832–1924), daughter of Anselm Salomon (1803–1874), who, like her cousin Emma, was born a Rothschild, married and died a Rothschild, also pursued music and musical composition beyond the confines of the drawing room. She was a pupil of Chopin.

Writing to her daughter-in-law, Hannah remarked that her niece Charlotte (1807–1859) was staying with them and that the talented Mathilde, then a young child, “performed quite extraordinarily on the pianoforte for her age.” Hannah added, “Charlotte’s sole desire is for the improvement in all respects of her children and is indefatigable for this purpose.”

Hannah Rosebery

“Her family is very interesting, the talents very conspicuous and execution the same.” But neither Emma nor Mathilde escaped the family strait-jacket; however, Hannah Rosebery (Hannah Rothschild, Countess of Rosebery)—the only child of Baron Mayer Amschel (1818–1874) and Julia (1831–1877), who married outside the faith—did so. She was heiress to a large fortune, a beautiful estate in the vale of Aylesbury and an extraordinarily fine collection of works of art which her father housed at Mentmore. She fell in love with Archibald Primrose (5th Earl of Rosebery, 1847–1929) and married him in 1878. Unhappily, she died at the early age of thirty-nine, shortly after the birth of her fourth child, and thus failed to witness the realization of one of her burning ambitions, to see her husband appointed Prime Minister.

Hannah became deeply interested in her husband’s “métier,” but since both she and Rosebery believed that women should not have a direct role in politics, she exerted her influence through subtle private and social means. Furthermore, she had the ability to encourage her husband to work when moods of intense lassitude descended upon him. Rosebery’s closest friend, Edward Hamilton, was her great confidante and he had no doubt about her ability, both on account of what he described as her “inherited business sense” and for being “a person born to direct.” He noted that she had a singularly well-balanced mind, remarkable for its common sense, and marked powers of judgement, which she was able to manifest in the form of good, and at times, critical advice. When Hannah fell seriously ill, Hamilton feared that “if anything happened to her, the future of politics might be seriously affected.”

Hannah discovered that the greatest contribution she could make to furthering Rosebery’s career—despite the advantages she could provide by her position as a well-informed “confidante” of politicians—was as a successful hostess. The faithful Hamilton, who helped with her guest list, admitted that he was appalled at the almost unbelievable amount of preparation and planning such entertainments required. But he was convinced that Hannah would do it better than anyone else. He subsequently reported, after her first reception at the Foreign Office, that “the arrangements were perfection.”

Winston Churchill gave us a fine appraisal of Hannah. In his essay on Rosebery he described her as “a remarkable woman upon whom Rosebery had leaned. ... She was a pacifying and composing element in his life which he was never able to find again because he never could give full confidence to anyone else.” He described Rosebery without her as “maimed.” Hannah certainly understood people and she had an unusual quality for one of her family: despite her passionate nature she faced life calmly, and overcoming her shyness she moved with poise and apparent serenity through society. Davies remarked that although she lacked “the stunning beauty of her cousins Laurie [Leonora (1837–1911)] and Evelina [1839–1866], Hannah had a serene and handsome beauty.”

Emma was impressed by Hannah’s power of hypnosis. She described how, on one occasion, a Russian princess who was traveling with the Mentmore house-party to watch the Derby at Epsom prevailed on Hannah to practice her power of suggestion upon her. At Hannah’s bidding the princess fell into a profound sleep and could not be roused for several hours, long after the party arrived at the Durdans. Hannah was frantic with fear and swore she would never again hypnotize a living soul. Did her scintillating, witty, eccentric daughter, Sybil (1879–1955), know of her mother’s gifts? Or did she discover her own psychic strengths by chance? We do not know.

Someone once remarked that what you learn from books or seminars at the university is unimportant. It is what you learn about people that really matters.

Extraordinary Hostesses

Entertaining, and the magnificence of such occasions, was far more important in the nineteenth century than it is today, and it was in this domain that the Rothschild wives and daughters excelled. Despite the luxury and gorgeous entertainment and in spite of the plethora of crowned heads, their parties were said to be most enjoyable, amusing and “not stiff.” One of the chief attractions were the interesting and distinguished people they collected together—musicians from Chopin to Rossini, writers and poets from Thackeray or Tennyson to Matthew Arnold or Henry James, painters like Ingres (who eventually produced a fine portrait of Betty, James’s niece and wife), statesmen from Disraeli to Bismarck, and princes from Edward VII to Napoleon III. Fortunately, Betty (1805–1886), and Leonora were startlingly beautiful. Count Conti described Julie (1830–1907)—also born a Rothschild and married a Rothschild—as “a lady of charm and distinction” (on the occasion when she entertained the Empress of Austria) and in his opinion Adelheid (1853–1935), who possessed a beautiful voice, was “brilliant and charming.”

Giving Back to Fellow Jews and the Poor

In quite another and more endearing sphere, these women were remarkably diligent and generous. In the nineteenth century and in the early days of the twentieth century there were no health service, no unemployment benefits, no old age pensions, no one-parent family benefits and no social security. People depended on private assistance rather than public support. But Jewish charity was different from any other. First and foremost, Jewish religious teachings laid down strict rules which had to be followed, directing the percentage of one’s worldly wealth which must be given away to the poor. This eliminated the “lady-bountiful syndrome.”

The resemblance of the wealthy Jewish merchant class to the evangelical women who glorified family values, distributed charity, and encouraged education was analogous but not homologous. Impecunious Jews had to combat dire poverty and face the calamities to which all human flesh is heir, but they also had to contend with the bitterness of antisemitism. This introduced a special element of sympathy and understanding into the relationship; it was not charity but a battle. When a poor lad who had regularly attended Nathaniel’s free reading room eventually became a senior wrangler at Cambridge, one more encounter had ended in a great victory.

Although, like their menfolk, the Rothschild wives first and foremost “worked hard for their fellow Jews,” their sympathy encompassed all the poor and needy.

Emma, when she came to Tring as a young bride, entered in her account book no less than four hundred charities. They ranged from repairs to several churches to payment of the passage of a pet lamb to Canada for two poor Jewish immigrants. Apart from personal matters she supported choral societies, lying-in societies, hospital equipment, convalescent homes (she built and equipped a small one herself in Tring), needlework, guilds, organ funds, Church Girls Union, Young Women’s Christian Association, Tring United Band of Hope, Literary Societies; she organized carving classes for children (with a tutor), a dancing class (with a dancing mistress), a club room and reading room, and eight pensioners’ cottages which she built in memory of her mother, Louise (1820–1894). Although large enterprises such as the building of hospitals, waterworks, laboratories and the Rothschild dwelling houses and so forth were generally left to the menfolk, their wives took an interest in more than local issues and both Emma and Connie Rothschild (Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea), for instance, worked tirelessly at ugly problems connected with the so-called White Slave trade.

As a child, eating my lunch, I overheard a conversation between my grandmother and a guest, in which the name of a certain member of the aristocracy was mentioned. “He keeps his cottages in very poor repair,” said my grandmother—and I felt the noble Lord was somehow shriveled to oblivion. My grandmother’s tone of censorious contempt comes rolling down the half-century, as if she had said it only yesterday.

The Eastern European Jewish women had, according to Naomi Shepherd, “been excluded from that intellectual inheritance which was the mainstay of Jewish life, while much of the responsibilities for family and communal survival had been placed on women’s shoulders.” Although this motif was evident everywhere in Jewry, in Western Europe it was in the process of crumbling at the edges.

Emma, for instance, was married to a man who like herself was a great reader, but he was strongly opposed to women’s suffrage, yet she herself—vote or no vote—felt perfectly competent to write a letter to the Prime Minister (Disraeli) both praising and criticizing his novel Endymion, a copy of which he had sent her.

Rothschild Women’s Community

There was one rather curious facet, however, of the men’s chauvinistic heritage: it resulted in the women forming an ill-defined, almost subconscious, yet very real Rothschild women’s “club.” They visited one another casually, gossiped and exchanged family news and discussed just those problems which applied to them and no one else in the community. They shared experience and understanding; they also talked with affection and giggled about their husbands and—in their opinion—their immensely gifted children. The Rothschild women really preferred each others’ company. It was in a sense traditional—a parallel but separate little world.

On one occasion Dorothy de Rothschild, James de Rothschild’s (1878–1957) youthful wife, was paying her daily visit to my mother and for some reason, which I cannot now recall, I was left alone to offer her tea. Rather at a loss for a suitable topic of conversation, I asked her advice on life—with a capital “L”—after one had left the school-room. “My dear child,” said Dolly, “I should imagine you will soon get married—so you should learn as soon as possible that you are a worm. A woman, to be a successful wife, must be a worm.”

Privately, I had reservations, since I could not imagine my grandmother a worm, even for one second! I looked at Dolly’s pretty smiling face and rosy cheeks and decided, despite my fifteen years of inexperience, that here at any rate was one contented, if faintly rueful, worm.

Strangely enough, the Rothschild women enjoyed greater ease than their menfolk. They had no material anxieties—although it was always said their bank deposits were full of their husbands’ worthless railway shares. They agonized over their loved ones’ health and peccadilloes but escaped the anxieties of the business world and the constant worry of the acute crises which arose from day to day in Europe during the nineteenth century.

Pride in Being Jewish and Successful

All but a few enjoyed the position they were assigned and obviously took great pride in a Jewish family’s rise to fame and fortune. They were greatly flattered by the visits of distinguished men of letters and artists of the day. Constance Rothschild, who was rather shallow and self-indulgent, again and again describes in her reminiscences the delightful conversations she relished with men like Morley, Balfour, and Meredith. Nevertheless, although there was no hint of open rebellion, an undercurrent of dissatisfaction existed—an impatience with the limiting position of the Jewish wife and mother, despite the powerful matriarchal role in the home which was their right. The letters from Charlotte (1819–1884) to her family in Frankfurt, after her marriage to Lionel, show this very clearly. But their social responsibilities were considerable and time-consuming. Certainly, the Rothschild wives played a not inconsiderable role in the progress and success of the first “European Economic Community.”

First published as “The Silent Members of the First EEC Family Reflections II: The Women” In Apollo Magazine, London