Hannah Floretta Cohen

"I would much rather people did not emphasize that I am the first woman President. I have to carry out the work of the Board whether I wear petticoats or trousers," said Hannah Floretta Cohen about her election to head the prestigious, traditionally male, Board of Guardians for the Relief of the Jewish Poor in Britain. In addition to her outstanding success at this job, she promoted many other Jewish and also non-Jewish organizations, through her skills in public speaking, financial expertise, and strategy building skills. She facilitated women's education and the provision of housing for convalescents and the elderly. Following her visit to Palestine, Cohen canvassed the support of British Jews for building a progressive, prosperous Palestine, loyal to Britain.

"I would much rather people did not emphasize that I am the first woman President [of the Board of Guardians]. I have to carry out the work of the Board whether I wear petticoats or trousers," said Hannah Floretta Cohen about her election to head the prestigious, traditionally male Board of Guardians for the Relief of the Jewish Poor in Britain (The Jewish Chronicle, June 20, 1930). In addition to her outstanding success at this job, she promoted many other Jewish and non-Jewish organizations through her skills in public speaking, financial administration, and strategy building. She encouraged and enabled women's education, as well as housing for convalescents and the elderly. Cohen also canvassed the support of British Jews for building a progressive, prosperous Palestine, loyal to Britain, after Britain received the mandate for its administration from the League of Nations in 1920.

Family and Education

Hannah Floretta Cohen was born in London, on May 25, 1875, into one of the leading Jewish families in nineteenth-century Britain. Her parents, stockbroker Sir Benjamin Louis Cohen and Louisa Emily Merton, were first cousins, grandchildren of Levi Barent Cohen, whose many descendants (including Lady Judith Montefiore and Constance Rothschild, Lady Battersea) were noted for their public service and philanthropy. Sir Benjamin had followed his eldest brother as President of the Board of Guardians for the Relief of the Jewish Poor (1887-1900). During his Presidency, he facilitated the emigration and repatriation of destitute Eastern European Jews, who he believed competed with the local working class for jobs and housing and whose alien ways, in his opinion, caused anti-Semitism. As a Conservative Member of Parliament (1892-1906), he supported the Aliens Act (1905) which curbed Jewish immigration to Britain. Hannah Cohen would continue her family's work, within and beyond the Jewish community.

Cohen was educated at home, together with her brothers. She took dictations in French and English when five years old, riding lessons at six, and dancing classes at seven. She also learned Hebrew, Latin, German, literature, and mathematics, and scored her brothers' cricket games. She participated avidly in adult conversations at her parents' dinner parties—discussion about current affairs, music, and books.

When Cohen was twelve, her elder brother's tutor reviewed her Latin homework and announced that she deserved the education of a boy. Her brothers' elite high schools did not accept girls. She studied at home until she was almost seventeen, when she gained admittance to Miss Lawrence's School, Brighton, later named Roedean College, to prepare for the Cambridge University entrance exams. At Miss Lawrence’s, she led debates, arguing clearly on almost any subject, participated in theatricals, and swam daily in the sea. She grasped the significance of liberty and would not conform to the Victorian ideal woman, a passive, graceful, and self-sacrificing “angel in the house” (as depicted in a popular poem by Coventry Patmore).

“New Woman”

At Cambridge University (1894-1897), Cohen became a “new woman,” a fin-de-siècle term for a woman who chose intellectual and physical activity rather than matrimonial achievement. Very few Jewish women attended Cambridge University in the nineteenth century. As a member of Newnham College, a women's college, Cohen studied for a BA degree in Classics. Newnham provided a safe environment for young women to attend university lectures and sit for university exams. She was not awarded a degree, however, as women were not deemed members of the University. In addition to reading Latin and Greek, she played energetically on the ladies' hockey team, wearing a necktie and a long dark skirt. She also played fives, a ball game popular at elite boys' schools, and joined the fire brigade. She skated from Cambridge to Ely when the river froze, smoked under the bridges, and invented excuses for returning late to college. This proved a happy and formative period of her life.

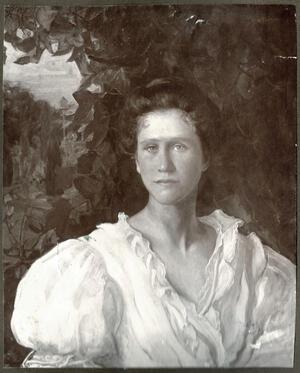

In the late nineteenth century, a woman's university education did not usually lead to an independent career. Cohen returned home to the life of a marriageable debutante, which involved weddings and balls, an introduction to the Queen (1898), and sitting for her portrait, but she did not marry. She helped her mother at fund-raising events and at her parents' country home in Kent and traveled abroad with her father.

Volunteer Work

Cohen understood the financial world in which her father's family made its fortune. She inherited his facility for public speaking and followed his footsteps both within and beyond the Jewish world. Her first social initiative was to persuade him to create a trust fund to enable less privileged Newnham students to buy books. Her concern to enable promising girls without means to receive education led her to become a generous benefactor when she inherited her own wealth. She promoted women's education and leadership through generous donations and her lifelong service on the governing bodies and financial committees of Roedean, Newnham College, Swanley Horticultural College for women, Hillcroft College for Working Women, and the University Women's Club.

Hannah Cohen proved as tireless as her father in her voluntary activities, applying her intellectual acuity, financial understanding, and vision to every social cause she promoted. Conservative and patriotic, she worked for a non-Jewish organization that promoted working women's emigration to British colonies, which she believed would strengthen the Empire.

War Work

World War I gave English women opportunities to enter the workforce. As large numbers of young men enlisted, women had to take over their jobs. Most middle- and upper-class women aided the war effort in traditionally feminine roles; they abandoned their sheltered lives to care for scarred and wounded soldiers. Cohen trained as a nurse, as did other women of her class, and worked at a Voluntary Aid Detachment hospital near her parents' home in Kent in the early years of the War. In 1916, she became honorary treasurer of the West Kent War Agricultural Committee, which recruited trained and untrained women for farm work. She continued this voluntary job until the end of the War.

In 1916, Cohen began full-time work in the Factory Department of the Home Office, which employed women to inspect factories, including the munitions factories, where women replaced enlisted men. Within a year she transferred to the Treasury, where she became one of the first women to undertake senior civil service. King George V awarded her the Order of the British Empire (O.B.E.) in March 1920, in recognition of her exceptional work as “Administrative Assistant” at the Treasury. With the war over, men returned to the office, and Cohen’s career ended.

Board of Guardians for Relief of the Jewish Poor

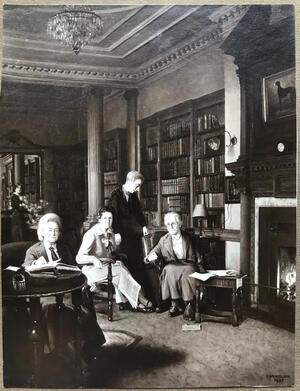

Cohen continued her volunteer work postwar. In 1900, following in her father’s footsteps, she had been elected the first female member of the Board of Guardians for the Relief of the Jewish Poor. In 1921, she was elected honorary secretary; in 1926, honorary treasurer; and in 1930, President.

On December 29, 1929, in a widely advertized Sunday morning radio broadcast, "This week's good cause," Cohen delivered the first radio appeal for funds for the cash-strapped 70-year-old Jewish Board of Guardians. During her goal-oriented presidency of the Board, her outspoken common sense, lucidity, vitality, and administrative skills characterized her leadership. She introduced and promoted programs for the prevention of poverty alongside the provision of relief. The changes she brought to the venerable organization included transferring relief for the sick, unemployed, and elderly from the Board to the Public Assistance Committees of the major local authorities; gaining state subsidies for the schools at the Board's convalescent homes; establishing a register of applicants for aid; collaborating with other charitable organizations; and building modern housing projects for families and for the aged, and convalescent homes for adults.

Palestine

In early 1922, as a member of the Economic Board for Palestine (a Jewish initiative), Cohen visited the region to study the land's commercial possibilities. She traveled from Tel Hai to Beersheba and from Tel Aviv to the Dead Sea and beyond, observing the ports, agricultural settlements, and a new brick factory. The strong, healthy women among the 17,000 Jewish pioneers working the land, mostly of Eastern European origin, reminded her of Britain's “Land Army Girls," who worked in agriculture in 1917-1918, replacing men who had been called up. In an interview published in both The Jewish Guardian and The Times on April 28, 1922, she called on British Jews to help the Zionist homeland prosper by providing capital for productive enterprises, because Palestine was strategically important for the British Empire. She argued that British Jews would repay in part their debt to England by helping to make Palestine a model state.

Two Books

In her final years, Cohen published two memoirs. The first, Changing Faces: A Memoir of Louisa Lady Cohen (1937), was about her mother, drawing on her grandmother's journals and her mother's letters and highlighting her family's role in the emancipation of the Jews and in shaping public opinion regarding Jewish persecutions. The second, Let Stephen Speak: A Memoir of Captain Stephen Behrens Cohen (1947), was about her nephew, a soldier who died of malaria in Pakistan in 1943. She established a scholarship and a travel fund in his name at King's College Cambridge for students from the Commonwealth and Palestine, "with a view to promoting friendship and understanding." She died of gangrene on November 21, 1946.

Alderman, Geoffrey. "Cohen, Hannah Floretta." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Braybon, Gail. Women Workers in the First World War. London: Croom Helm, 1981.

Cohen, H. F. "Reminiscences of Old Roedeanians:1892-93”. Roedean School Magazine, (June 1935): 51-54.

Kuzmack, Linda Gordon. Woman’s Cause: Jewish Woman’s Movement in England and the United States, 1881–1933. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University Press, 1990.

Lipman, V. D.. A Century of Social Service, 1859-1959: The Jewish Board of Guardians. London: Routledge and K. Paul,1959.

London Gazette Supplement (March 26, 1920): 3781.

Merton, Hannah Moses. Journal 13, April 5, 1887. Richard Levy Family Archive.

"Palestine Pioneers: An English Jewesses' Impressions," The Times and The Jewish Guardian, April 28, 1922.

Richard Levy Family Archive, Israel.

Sutherland, Gillian. In Search of the New Woman: Middle-class Women and Work in Britain, 1870-1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

The Woman's Leader (March 5, 1920): 100.

The Woman's Library, London School of Economics, file 7JPS/B/07.