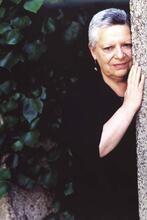

Achy Obejas

Achy Obejas is the author of journalistic pieces, novels, short stories, and poetry that explore identity, desire, nationality, isolation, loss, and self-discovery. She has also edited literary collections and translated major works, including Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. She works as a writer and editor with Netflix on global material marketed in the United States. With her second novel, Days of Awe (2005), Obejas began to explore Jewishness and Cuban Jewish cultures, both professionally and personally. The novel was selected as a best book of the year by the LA Times, Philadelphia Inquirer, and Washington Post. She has also received two Lamda Literary prizes, the Pulitzer Prize, and a NEA fellowship and was nominated for a PEN/Faulkner Award, among other accolades.

Author, journalist, and activist Achy Obejas was born in Havana, Cuba, on June 28, 1956, and has lived in the United States since she was six years old. Obejas lives at the intersection of multiple identifies, but she has repeatedly asserted that her Cuban birth has been a central defining circumstance of her life. Indeed, she has described herself as being “endlessly Cuban,” along with the various other descriptors that she claims and that have been assigned to her over the years (Shapiro, Feal). While she is probably best known as female, Cuban/Cuban American, and queer, Obejas also has important connections with Jewishness and Jewish writing. These connections have increasingly informed her writing over the years and helped shape the multiple and multidirectional trajectories that she explores personally and professionally.

Early Career and Literary Works

Obejas and her parents left Cuba for the United States in 1962 and settled soon after in Michigan City, Indiana. After attending college at Indiana University and receiving an MFA in Creative Writing from Warren Wilson College, she moved to Chicago where she lived for several decades and worked extensively as a journalist, publishing in the Windy City Times, The Chicago Reader, the Sun Times, and the Advocate. Chicago area readers likely know her best for her work with the Chicago Tribune, including an “After Hours” column about the city’s night life that highlighted some of the lesser-known venues and events in the smaller ethnic neighborhoods outside of “the loop” and the city center.

Obejas’s first major publication as a fiction writer was a collection of short stories, We Came All the Way from Cuba so you Could Dress Like This? (1994). The stories feature the complexities of intergenerational dynamics within immigrant/transcultural families—as the title of the collection and final story therein suggest—along with a cast of characters who dance around the margins of society, sometimes lamenting yet often reveling in their inability to fit neatly into established categories or be contained within typical boundaries. Her first novel, Memory Mambo (1996), took these themes even further: the story traces the ups and downs of a female couple, one Puerto Rican and one Cuban, unpacking the contours of their cultural and political differences, how they relate to one another, and how they seek to (re)define their sexuality and their identifies over the course of the novel.

Days of Awe and the (Re)Turn to Jewishness

Obejas’s early work earned significant critical acclaim and established her as a leading figure, especially in Latinx and LBGTQ literary circles. Her connection with Jewish literature emerged with her next novel, Days of Awe (2001). As in many other languages, Spanish surnames closely associated with trades and professions often signaled Jewish roots; when required by state authorities or officials to register both a first and last name, it was common for Jews to adopt a name closely associated with a place or occupation. Obejas, which means sheep in Spanish, suggests the prospect of Jewish and/or Crypto-Jewish ancestors who were shepherds or farmers. When this possibility was suggested to Achy, she became intrigued and began to research her family history.

According to Obejas, her family had interactions with the synagogue and local Jewish community when she was a child, yet she was not aware of any direct ties to the Jewish community at that time. At one point, she discovered a Four-cornered prayer shawl with fringes (zizit) at each corner.tallit among her father’s possessions, but she did not understand its significance. Following an extensive conversation with Judith Wachs, of the Descendants of the Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal before the explusion of 1492; primarily Jews of N. Africa, Italy, the Middle East and the Balkans.Sephardic music group Voice of the Turtle, about anusim (Jews who were forced by the Spanish Inquisition to convert to Catholicism) and the history of Sephardic Jews, Obejas began to explore the family history more actively. A cousin who lived in Madrid was particularly helpful, and she was unearthed a complex set of ancestral connections with Judaism and the Inquisition. This process led her to write Days of Awe (in which Wachs is acknowledged), which is not strictly autobiographical but incorporates many details from her own experiences and what she learned about both her family and Sephardic Jewish history more generally. This research and the writing of Days of Awe also led Obejas’s father, who had previously been evasive on the topic, reconnecting with his Jewishness and some Jewish community organizations. When he passed away, at her mother’s behest, Obejas included a reading by Judah Halevi (a famous medieval Spanish Jewish writer) at his funeral in order to honor this legacy. She also began to identify more as Jewish as a result of these experiences, incorporating Jewish rituals and practices into her life, raising her children as Jewish, and even joining a local synagogue in California.

The protagonist of Days of Awe embarks on a similar journey, unearthing her Jewish roots as part of her journey of self-discovery. The protagonist, Ale, was born in Cuba and raised in the United States. She was aware of family ties with Jewish culture, but she learns that those ties are much closer than she had previously understood when she realizes that her father was a practicing Jew; this realization allows her to revisit early childhood memories of her father wrapping black leather straps around his arm and fingers in their basement, which she now recognizes as him secretly binding Phylacteriestefillin, in the same way that the author discovered and then later understood the significance of her father’s prayer shawl. Over the course of the novel, Ale navigates intersections between her family’s trajectory and her own journey, which weaves together her sexuality, her work as a translator, her transcultural connections in Cuba and the United States, and her religious heritage. Of course, the novel takes its title from the cycle of self-examination, repentance, and renewal associated with the Jewish New Year. The journey of self-discovery and the reinterpretation of childhood memories depicted in the novel is also a familiar narrative for many Cuban Jews and other groups with crypto- or repressed Jewish roots. Members of the Jewish community in Havana often share anecdotes—whether their own or as related to them by others—about childhood memories for which the religious significance was only understood later, after the Jewish roots had been discovered (i.e., always having candles with Friday night dinner, older relatives who regularly touched the doorposts they entered the home). In this sense, Days of Awe stages a particular relationship with collective memory that many members of the Cuban/Cuban-Jewish community share. The novel is also part of a trend within contemporary Cuban literature and culture that highlights groups that had been marginalized in the mid-twentieth century and (re)asserts their roles in Cuban culture and society.

Later Literary Works

Obejas’s more recent books have also presented an array of unconventional characters and stories that underscore the complexity of Cuban culture and experiences, both on the island and in the diaspora, along with explorations of other cultural contexts. Ruins (2009) follows the rather small-scale—geographically speaking—odyssey of Usnavy and his valiant attempts to provide for his family. The plot centers largely around several old lamps among Usnavy’s collection of knick-knacks and other inherited and found objects, which he believes may prove to be from the small set of legendary Tiffany lamps rumored to still exist (undetected) in such collections on the island. If true, the prized object(s) would command a small fortune that could liberate Usnavy and his family from the daily struggles and perils they face during an era of increased scarcity and precarity in Cuba following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Tower of the Antilles (2017) represents a return to the short story genre for Obejas. It is a collection of closely connected (sometimes intertextually linked) pieces that move among Cuba, the United States, and the Maldives and weave together narrative prose, abstract pieces with a more poetic style, and texts comprised of a series of vignettes framed by the auditory perceptions of a character who is progressively losing her hearing. In this work, the decaying edifices of Havana from Ruins are interwoven with remote sites on distant shores. Not only do the characters experience isolation within the figurative “islands” they inhabit (in the cornfields, along a shoreline, at sea, trapped in the snow), they move between islands throughout the stories in the collection. Indeed, Tower of Antilles begins and ends with the portrayal of movement to, from, and among islands as it explores how geography and roots/being uprooted can foster connections, entanglements, and alienation.

Although these later works do not focus on Jewish characters and themes to the same degree as Days of Awe, Jews and Jewishness make minor appearances, signaling their ongoing significance both in the Cuban cultural landscape and the author’s imagination. Also, as with Days of Awe, these later works are indebted to specific circumstances or developments in Obejas’s personal life. Ruins was written following a period during which Obejas lived and worked in Cuba for extended periods, and the contents of the novel reflect a rich understanding of the trials and tribulations of daily life in Havana — a portrait that can be extremely hard to truly apprehend as an occasional visitor. According to the author, both the form and content of Tower of the Antilles are marked by developments in her professional and personal life: the characters and settings have broadened to explore greater movement and connections across diverse groups and contexts, and the return to the short story form reflects—among other things—the ways in which her writing needed to adapt to the demands of other professional commitments and, in particular, motherhood.

Major Themes, Impact, and Achievements

Through all of these works, Obejas weaves together stories about marginalized or unsettled characters who experience a moment of discovery or self-realization. She brings together disparate elements—whether within a single character or setting or across several—that defy conventional labels and simple categorizations, creating complicated layers of identification that often remain provocatively unresolved.

Along with this corpus of prose, throughout her career Obejas has also written poetry in Spanish and English that explores some of these same major themes, offering moving glimpses of longing, desire, aimlessness, loss, isolation, pleasure, and joy. Readers of her prose will undoubtedly find her poetic voice familiar; at times, the poems almost seem to linger in some of the more evocative moments from her novels and short stories.

Obejas has won numerous literary awards and accolades over the years, including the Pulitzer Prize, the Studs Terkel Prize, and two Lambda Literary awards, along with several appointments as a visiting profession or writer in residence at various colleges and universities. She has worked extensively as a bilingual translator, introducing English-speaking audiences to prominent contemporary Cuban women writers and making English-language works by United States Caribbean writers such as Junot Díaz and Rita Indiana accessible in Spanish. She also works with Netflix on global projects. Obejas co-edited a volume with Megan Bayles entitled Immigrant Voices: 21st Century Stories (2014) and has written a bilingual book of poetry, Boomerang/Búmerang, that continues her exploration of Jewish content. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area with her children.

Selected Works by Achy Obejas

We Came All the Way from Cuba so You Could Dress Like This? Pittsburgh: Cleis Press, 1994.

Memory Mambo. Pittsburgh: Cleis Press, 1996.

Days of Awe. New York: Ballantine Books, 2001.

Ruins. New York: Akashic, 2009.

Co-editor, with Megan Bayles. Immigrant Voices: 21st Century Stories. Chicago: Great Books Foundation, 2014.

The Tower of the Antilles. Brooklyn, New York: Akashic Books, 2017.

Boomerang/Bumerán. Boston: Beacon Press, 2021.

Bajini, Irina. “‘¿Qué Se Te Perdió En Cuba?’ La Doppia Diaspora Della Comunità Ebreo-Cubana Nelle Pagine Di Ruth Behar e Achy Obejas.” Altre Modernità, 2014, pp. 200–209.

Cooper, Sara. “Queering Family: Achy Obejas’s ‘We Came All the Way from Cuba So That You Could Dress Like This?’” Chasqui: Revista de Literatura Latinoamericana, 3. 2 (2003): 76–88.

Feal, Rosemary G., organizer; Cooper, Sara E., Dykstra, Kristin, Goldman, Dara E., Maguire, Emily A., panelists. “Endlessly Cuban: A Discussion on the Work of Achy Obejas With the Author.” Modern Language Association Conference, January 2019, Chicago, IL.

Feal, Rosemary G. and Goldman, Dara. E. “A Creative Conversation with Achy Obejas.” Modern Language Association Conference, January 2019, Chicago, IL.

Goldman, Dara E. “Next Year in the Diaspora: The Uneasy Articulation of Transcultural Positionality in Achy Obejas’s Days of Awe.” Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies, vol. 8, 2004, pp. 59–74.

Goldman, Dara E. “Unruly Subjects: Examining the ‘Endlessly Cuban’ Contours of Achy Obejas’ Narrative Universes.” Modern Language Association Conference, January 2019, Chicago, IL.

Quesada, Sarah. “Tower of the Antilles and a Literary Life in Retrospect.” Latino Studies 18.1 129-36.

Shapiro, Gregg. “In ‘AWE’: Achy Obejas on her new work.” Windy City Times, August 8, 2001.

Wolfenzon, Carolyn. “Days of Awe and the Jewish Experience of a Cuban Exile: The Case of Achy Obejas.” Hispanic Caribbean Literature of Migration: Narratives of Displacement, edited by Vanessa Pérez Rosario, 105-118. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.