Ministering Women and Their Mirrors

Ancient Silver and copper alloy Egyptian Mirror, Reportedly From Aswan, Egypt, c. 1478-1390 B.C.E., Brooklyn Museum.

Two verses in the Hebrew Bible refer to women ministering in the Tabernacle (Exodus 38:8 and 1 Samuel 2:22). These women gathered around the entrance and donated their copper mirrors to the making of the basin where the priests would wash before entering the sanctuary. Yet neither the nature of their service nor the original purpose of the mirrors are known. The historical critical approach conjectures that these women served as guards at the Tabernacle’s entrance, warding off evil with their mirrors. The midrash, however, retells the story of the women’s mirrors with which they seduced their husbands in the fields. Despite Moses objection, God urges that the mirrors be accepted because it was they that “raised up the hosts” of Israel in Egypt (Exodus 12:41, 51).

Only two verses in the Hebrew Bible attest to women serving in the Tabernacle (Exodus 38:8 and 1 Samuel 2:22). The paucity of information about their identity and the nature of their service hints at another narrative lying below the surface that may mysteriously have been suppressed. Two main approaches to filling in this gap exist. The first, a historical critical approach, entails a reconstruction of what these women might have been doing based on intertextual resonances and evidence from parallel ancient Near Eastern texts and artifacts. The second draws on classic rabbinic midrash, which retells the story of the women’s donation of mirrors to the making of the Tabernacle. In a creative play with language in the midrash, it is not the women who “ministered” or “served” [ha-tzov’ot], but the mirrors that “raised up the hosts” [ha-tzeva’ot] of Israel. These generative mirrors are melted down to make the basin where the priests wash before entering the holy sanctuary. These two windows into the biblical text provide different feminist reading strategies for reclaiming the untold stories of women in the ancient world.

The Mirrors and the Copper Basin of the Tabernacle

The copper basin (or laver) is first described in the context of the detailed instructions for the making of the Tabernacle (Exodus 30:18), but no further details about how the laver should be made are offered. A later description of the furnishings of the sanctuary provides an additional, curious detail:

And he made the laver of copper and its base of copper, from the mirrors of the ministering women who ministered [ha-marʾot ha-tzovʾot ’asher tzav’u] at the entrance to the tent of meeting (Exodus 38:8, author’s translation).

Who were these women and why even mention their service, when “the tent of meeting” (also called the Tabernacle) has not yet been completed? Where did these mirrors come from? Why were they not included in the original list of materials donated towards the making of the Tabernacle (Exodus 25)?

Mirrors in the Ancient World

The word “mirror,” in Hebrew mar’ah (plural marʾot), appears nowhere else in the Hebrew Bible. Based on archaeological findings dating from the mid-2nd millennium until the 7th c. BCE, we know that ancient mirrors were traditionally slightly convex and made of copper, bronze, or brass, highly polished to allow for the reflection of a face. Images from ancient Egyptian painting and carvings suggest that they were used by both men and women in applying makeup to their faces. In myth, the use of mirrors can have lethal consequences, as when Perseus deployed his shield as a mirror to slay the Medusa or when Narcissus gazed at his own reflection in the river. Further, mirrors served as a symbol for women and femininity. The Egyptian word for mirror, ankh, also means “life” and has strong female associations. The symbol for female or woman (based on the sign for Venus) evokes the ancient hand-held mirror:

The Ministering Women

Yet we don’t know what the function of these mirrors was in the biblical context. Further, we are not told what role “the ministering women [ha-tzovʾot]” was. Only one other verse, in the context of the Tabernacle set up at Shiloh, alludes to these women “who performed tasks [ha-nashim ha-tzovʾot] at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting” (1 Samuel 2:22, NJPS translation). The description of these women gathered at the threshold of the sanctuary may borrow from the verse in Exodus, suggesting that women played a role in the Tabernacle perhaps before the priestly and levitical functions were formalized. The verb “to minister” or “perform tasks” (tz.b.’.) is often associated with military groupings, “soldiers, troops or companies” (as in Numbers 2:4, 6, and 10), but it can also refer to the performance of cultic tasks (as in Numbers 4:23, 34 39, 43, and 8:24-25).

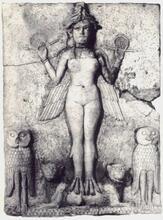

Surveying the archaeological evidence in the ancient Near East, Susan Ackerman discovered female figurines (usually two) flanking the entrance to Canaanite and Egyptian shrines. These figures operated as “divine agents” to ward off evil at the threshold where danger threatened to encroach from outside. Janet Everhart also points to comparative evidence, such as women’s cultic role at a shrine in 14th-century Susa and the role of Arabic women associated with the kubbe (5th-6th-century BCE), a structure strikingly similar to the ark, which the women accompanied (mounted on camels) into battle. The “ministering women [ha-tzovʾot],” then, may refer to Israelite female guardians serving at the tent of meeting and ark, perhaps even accompanying it into battle. Somewhere, the story of their sacred role was lost or erased by the priestly sources and historical record; only these two vestigial verses remain.

The Mirrors in Midrash

The midrashic account of the righteous women of the Exodus and their mirrors tells yet another story. According to the aggadah, Israel was redeemed from Egypt on account of the merit of the righteous (unnamed) myriad of women who raised up the host of Israel (Babylonian Talmud Sotah 11b). Because of Pharaoh’s harsh decrees separating man from wife, the women went out to the fields with food and drink and seduced their husbands. They conceived and bore many children (some say each woman bore twins, some say sextuplets), which would account for the uncanny growth of the Israelite population over the course of four generations from the twelve sons of Jacob and their families to the 600,000 “hosts of Israelite” men (closer to two million if women and children are included). The later midrash Tanḥuma-Yelamdenu (a Palestinian homiletical compilation, 8th-9th c. CE) grants the mirrors special agency in the women’s uncanny fertility:

The women would go down to draw water from the river. Whereupon the Blessed Holy One prepared small fishes for them inside their jars. They would cook some, sell some and buy wine with the proceeds and go out into the fields and feed their husbands there…. After they had eaten they took out their mirrors and looked into them together with their husbands. She would say, “I am more beautiful than you.” He would say, “I am more beautiful than you.” As a result, they would arouse them to sexual desire … (Tanḥuma Pequdei 9, author’s translation).

These same mirrors, the midrash tell us, were later given by the women to make the basin in the Tabernacle where the priests would purify themselves before making their offerings on the altar. Though Moses objected to these symbols of vanity as a legitimate contribution, threatening to “break the [women’s] thighs,” God overrode the prophet, saying: “Through the merit of those mirrors that they showed to their husbands and through which they aroused them … —those same mirrors raised all those hosts [tzeva’ot]” (see Exodus 12:41, 51). That is, it was the mirrors that raised up all the hosts, according to the midrash; they are the subject of the verb tzovʾot in Exodus 38:8, not the women.

In contrast to the historical-critical method, midrash is associative, drawing on common tropes like the “righteous seductress.” Moreover, it uses creative grammar, where the subject of the verb shifts, personifying the mirrors themselves as change-agents who “raise up the hosts of Israel.” In this midrash, God is seen to be on the side of women, with their audacious mission to guarantee that “life find a way,” while Moses is rebuked for rejecting the mirrors. When God defends the women’s donation of the mirrors against Moses’ violent (and prudish) rejection, their significance as icons of vanity is transformed into emblems of resistance, even transformation.

Ackerman, Susan. “Mirrors, Drums, and Trees,” Vetus Testamentum Supplements vol. 148 (2012): 537-567.

Adelman, Rachel. “A Copper Laver Made from Women’s Mirrors”. https://thetorah.com/a-copper-laver-made-from-womens-mirrors/, March 2018.

Everhart, Janet S. “The Serving Women and Their Mirrors: A Feminist Reading of Exodus 38:8b.” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 66.1 (2004): 44-54.

Zornberg, Avivah Gottlieb. The Particulars of Rapture: Reflections on Exodus. New York: Schocken, 2001.