Midwife: Bible

Like all traditional peoples, the Israelites had health-care professionals—midwives—who specialized in attending women in childbirth. Midwives appear in several biblical narratives, including the well-known story of two midwives who disobey pharaoh’s order to kill Hebrew babies at birth; and God is depicted metaphorically as a midwife in one poetic text. Ancient Near Eastern documents include obstetrical handbooks, and Israelite midwifes likely had similar bodies of knowledge. The experience of midwives as health-care professionals would have given them the status of experts in Israelite society.

Midwives in the Bible

When the matriarch Rachel is giving birth to her second son (Benjamin), she is attended by a midwife (Gen 35:17). The presence of such a health care professional, called meyalledet (“one who causes, helps birth”), was probably routine in Israelite and pre-Israelite society, and the explicit reference to her in this case is not necessarily related to the difficulty of Rachel’s labor.

Similarly, the presence of a midwife at the birth of Tamar’s twin sons seems routine (Gen 38:28). But the role of the midwife in this narrative is hardly routine. She witnesses and verifies the strange reversal of the birth sequence whereby Perez precedes Zerah, although the latter’s hand had appeared first and had been marked with a crimson thread. Further, the midwife apparently suggests appropriate names for the newborns, usurping a role usually played by one of the parents, often the mother. The remarkable reversal gives priority and recognition to Perez (“breach”), who becomes an ancestor of King David.

Two midwives, Shiphrah and Puah, have an important role in the exodus story (Exod 1:15-21). They claim that the Hebrew women are “vigorous” and give birth before the midwives arrive, thus precluding obedience to the pharaoh’s orders to kill infant boys at birth. In this act of ‘”civil disobedience,” they save the lives of Moses and other male infants.

The belief that god is the creator of life underlies the metaphor of God as a midwife, one of several female metaphors for God in the Hebrew Bible (e.g., God as mother in Hos 11: 3-4 and Isa 45:10-11) One of the psalms contains the words of a man who is in serious danger and petitions God to rescue him. God brought the psalmist into life: “You [God] drew me from the womb, kept me safe at my mother’s breast” (Ps 22:11). Thus God should also sustain the psalmist’s life. This image of God as midwife is related to the belief that God opens the wombs of women hoping to become pregnant (Leah, in Gen 29: 31-32; Rachel in Gen 39:22).

Midwifery in the Ancient World

Midwifery is among the earliest and most ubiquitous specialized functions in human society. It virtually always is a woman’s profession: it involves women assisting other women in a natural biological process. As a profession, it involves the instincts and emotions of the practitioners as well as technical knowledge and clinical skill. The care of a midwife tends to be holistic, providing emotional as well as physical support and assistance, as the case of Rachel indicates. In her duress, Rachel evidently exhibits fear, and the midwife consoles her.

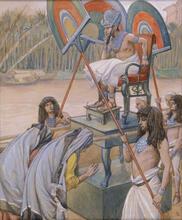

The existence of texts with rules and procedures for obstetrics in second-millennium BCE Egypt, where midwives (and birth deities) were female, indicates that bodies of knowledge about obstetrical practice were collected and transmitted, whether in written or oral form. Very little direct knowledge about Israel’s health care system is available, but biblical clues and comparative research indicate the existence of a developed system with several consultative options. The midwife was the only one of those options outside priestly or prophetic circles. The professional aspects of midwifery meant that midwives had to train their successors. Informal associations of midwives helped maintain and add to the knowledge of delivery techniques, medications given to women in labor, and also prayers to be uttered at childbirth (Isa 46:16–18). Midwives in ancient Israel thus represent one of several female professions—others were wise women, musicians, and mourners—that afforded women the opportunity to meet with one another, instruct novices, and garner respect for their skills from the community. The status of midwives—and their power to transform childbirth from what might be a negative experience to a positive one—did not erode until the advent of modern, male-dominated medicine.

Claassens, L. Juliana M. “Rupturing God language: The Metaphor of God as Midwife in Psalm 22.” In Engaging the Bible in a Gendered World: An Introduction to Feminist Biblical Interpretation in Honor of Katherine Doob Sakenfeld, edited by Linda Day and Carolyn Pressler, 166–175. Louisville and London: Westminster, 2006.

Meyers, Carol. “Guilds and Gatherings: Women’s Groups in Ancient Israel.” In Realia Dei: Essays in Archaeology and Biblical Interpretation in Honor of Edward F. Campbell, Jr. at His Retirement, edited by Prescott H. Williams, Jr. and Theodore Hiebert, 154–184. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1999.

Towler, Jean, and Joan Bramall. Midwives in History and Society. London: Routledge, Kegan & Paul, 1986.