Martyred Mother with seven sons (2MACC): Apocrypha

The book of 2 Maccabees tells the story of a family of seven sons and an unnamed mother who sacrifice their lives in the name of religious freedom. King Antiochus IV of the Seleucid empire outlaws observance of Jewish holidays and worship. When the family is arrested for breaking these laws, they are tortured by the King who attempts to feed them swine flesh. The mother, who acts with a woman’s reasoning and a man’s courage, encourages her sons to refuse to obey the King and all choose martyrdom. The death of the family is the culmination of a martyrology that lasts from 2 Macc 6:37–38; 8:3–5.

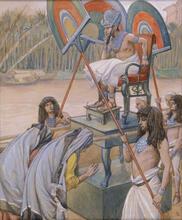

Martyrdom under King Antiochus IV in 2 Maccabees

According to 2 Maccabees, in the second century B.C.E. the Seleucid king Antiochus IV outlaws temple worship, observance of Sabbaths and holy days, circumcision, and the keeping of (Torah she-bi-khetav: Lit. "the written Torah." The Bible; the Pentateuch; Tanakh (the Pentateuch, Prophets and Hagiographia)Torah), and rules that the Jews who will not adopt Greek customs are to die (2 Macc 6:9). The martyrology in 2 Macc 6:7–7:42 (the first of its kind in the Bible) lists stories of those who choose death over apostasy. The last martyr is the unnamed mother who dies after witnessing each of her seven sons cruelly tortured. Her family story appears here in 7:1–42 and in a considerably expanded version in 4 Maccabees. Exactly where the martyrdoms in 2 Maccabees take place is debated. No scene other than Jerusalem and Judea is ever established in the narrative, yet Antioch is a possible setting for chap. 7 since the king seems so thoroughly on his own turf.

The 2 Maccabees 7 version of the martyr family story opens with the arrest of the seven brothers and their mother, who are beaten in an effort to force them to eat swine’s flesh (prohibited by Lev 11:7–8). The first six sons each defy the king and are cruelly tortured. The six brothers’ exchanges with Antiochus IV, the king (7:2–19), build a coherent argument, which is arranged chiastically (three elements and their reverse): (A) Jewish refusal of the king’s command results in suffering and death; (B) Jewish hope in eternal life is born of serving the King; (C) Jewish belief in bodily resurrection makes mortal life meaningless; (C') for the gentile king there will be no resurrection to life; (B') for this mortal king and his descendants there is no hope; (A') the king’s “fight against God” (7:19) will not go unpunished. God, not the gentile king, is in charge of the happenings.

The Role of the Mother in the Martyr Family

Attention then turns to the mother (7:20–23), “especially admirable and worthy of honorable memory” (7:20). Because her hope was in the Lord, she had encouraged each of her sons, in Aramaic or Hebrew, to persevere. “Filled with a noble spirit, she reinforced her woman’s reasoning with a man’s courage” (7:21). Addressing these sons—not Antiochus—she claims not to comprehend how life came to them in her womb, even as she expresses confidence in the Creator, who “will in his mercy give life and breath back to you again, since you now forget yourselves for the sake of his laws” (7:23). What mother, beholding the brutal deaths of six sons, could speak such words?

Antiochus interprets her words, which he cannot understand since they are not in his language, as reproach, and so appeals to her seventh and youngest son that he will make him rich and will befriend him if he will but turn away from the ways of his ancestors (7:24). When the youngest will not listen, Antiochus calls the mother and urges her to persuade her son (7:25). The mother leans close to her remaining child and, speaking only to him, urges him to take pity on her and accept death (7:27–29).

Three matters in her words merit notice: (1) the mother speaks only to her family members, never the king; (2) the mother remarks in passing that she had nursed her son for three years; (3) God creates out of nothing, which may reflect the philosophical argument creatio ex nihilo, or more likely, with 7:11, 22–23, belief that life comes from the Creator of the world.

The Seventh and Youngest Brother

While his mother was still speaking, her youngest says to the king, “What are you waiting for? I will not obey the king’s command, but I obey the command of the law that was given to our ancestors through Moses” (7:30). Repeating much of what his brothers said as they faced their deaths, the seventh brother claims that the king will not go unpunished, that suffering is discipline for human sinfulness, and that reconciliation with God is at hand (7:31–36). Antiochus falls into a rage and treats the youngest brother worse than the others (7:39). “So he died in his integrity, putting his whole trust in the Lord” (7:40).

“Last of all, the mother died, after her sons” (7:41). With only this brief statement the mother’s death is recorded.

Antiochus’s brutal efforts are completely ineffective. Death has lost its power in the face of obedience to the laws of the ancestors and belief in God’s mercy and resurrection of the dead. Resurrection cancels fears of earthly death for faithful Jews. Which sins merit martyrdom is a question left unanswered. Vengeance and vindication belong to God alone—not the earthly king, Antiochus.

A Mother with Masculine Virtues

2 Maccabees, like 4 Maccabees, shows that eusebes logismos, “reason adhering to the law,” triumphs over human emotions (see 4 Macc 1:16–19). Those who might be expected to be weak show themselves strong in holding fast to the teachings of the Torah.

Ironically, the king is the only one in the story who loses control. The author’s claim that the mother bore the deaths of her sons with good courage because of her hope in the Lord and the reinforcement of “her woman’s reasoning with a man’s courage” (7:20–21) reflects the Greek cultural norm, mediated through Hellenism, that courage and control are distinctively masculine virtues. Thus praise comes for being like a man. This mother, unlike her counterpart in Jer 15:5–9, did not swoon, nor is she disgraced by her children or her own actions. She is mother of a martyr family that was unified in facing death, with no husband or father offering protection. The unexplained absence of her husband makes her a virtual widow. Courage such as hers and that of her sons won God’s mercy and made possible the victories of Judas Maccabeus.

The martyrology, set in Judea and Jerusalem, that stretches from 2 Macc 6:37–38; 8:3–5, beginning with the deaths of the circumcising mothers and climaxing with the martyrdom of the mother and her seven sons, now comes to an end. Antiochus and his ideology do not win the day. Two Jewish women, Sabbath observers assembled in caves, an old man (Eleazar), seven brothers, and a single mother have shown conclusively that God disciplines the faithful, but never withdraws mercy (see 6:12–17).

Doran, Robert. “2 Maccabees.” In The New Interpreter’s Bible, edited by Leander E. Keck, 4:179–299. Nashville: 1996.

Goldstein, Jonathan A. II Maccabees: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Garden City, NY: 1983.

Meyers, Carol, General Editor. Women in Scripture. New York: 2000.

Young, Robin Darling. “2 Maccabees.” Women’s Bible Commentary, edited by Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, 322–325. Kentucky: 1998.

Ibid. “The ‘Woman with the Soul of Abraham’: Traditions about the Mother of the Maccabean Martyrs.” In “Women Like This”: New Perspectives on Jewish Women in the Greco-Roman World, edited by Amy-Jill Levine, 67–81. Atlanta: 1991.